Published online Jul 18, 2024. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v15.i7.627

Revised: May 8, 2024

Accepted: May 27, 2024

Published online: July 18, 2024

Processing time: 132 Days and 9.6 Hours

Tobacco use is a well-documented modifiable risk factor for perioperative complications.

To determine the tobacco abstinence rates of patients who made cessation efforts prior to a total joint arthroplasty (TJA) procedure.

A retrospective evaluation was performed on 88 self-reported tobacco users who underwent TJA between 2014-2022 and had tobacco cessation dates within 3 mo of surgery. Eligible patients were contacted via phone survey to understand their tobacco use pattern, and patient reported outcomes. A total of 37 TJA patients participated.

Our cohort was on average 61-years-old, 60% (n = 22) women, with an average body mass index of 30 kg/m2. The average follow-up time was 2.9 ± 1.9 years. A total of 73.0% (n = 27) of patients endorsed complete abstinence from tobacco use prior to surgery. Various cessation methods were used perioperatively including prescription therapy (13.5%), over the counter nicotine replacement (18.9%), cessation programs (5.4%). At final follow up, 43.2% (n = 16) of prior tobacco smokers reported complete abstinence. Patients who were able to maintain cessation postoperatively had improved Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-10 mental health scores (49 vs 58; P = 0.01), and hip dysfunction and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint replacement (HOOS. JR) scores (63 vs 82; P = 0.02). No patients in this cohort had a prosthetic joint infection or required revision surgery.

We report a tobacco cessation rate of 43.2% in patients undergoing elective TJA nearly 3 years postoperatively. Patients undergoing TJA who were able to remain abstinent had improved PROMIS-10 mental health scores and HOOS. JR scores. The perioperative period provides clinicians a unique opportunity to assist active tobacco smokers with cessation efforts and improve postoperative outcomes.

Core Tip: From a retrospective review of 37 self-reported tobacco users undergoing total joint arthroplasty, we found a tobacco cessation rate of 43.2% at nearly 3 years postoperatively. These patients had improved Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-10 mental health scores and hip dysfunction and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint replacement scores.

- Citation: Kim BI, O'Donnell J, Wixted CM, Seyler TM, Jiranek WA, Bolognesi MP, Ryan SP. Smoking cessation prior to elective total joint arthroplasty results in sustained abstinence postoperatively. World J Orthop 2024; 15(7): 627-634

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v15/i7/627.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v15.i7.627

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable disease, morbidity, and mortality in the United States, with estimated healthcare costs exceeding $240 billion dollars annually[1]. Smoking shortens people's lives by an average of 10 years compared to non-smokers. This is secondary to coronary heart disease, aneurysms, atherosclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancers associated with tobacco use[2].

Tobacco use is a well-documented modifiable risk factor for many negative outcomes in orthopedic surgery. An increased risk of infection and wound complications is documented in every orthopedic subspecialty with tobacco use perioperatively[3-7]. In total joint arthroplasty (TJA), tobacco users have higher rates of wound complications and prosthetic joint infections (PJI) than non-users[8]. Former smokers have a lower risk of complications after TJA than current smokers, indicating that cessation efforts can have clinically relevant impacts on postoperative outcomes[8].

Smoking cessation's correlation with improved clinical outcomes in TJA is well-recognized[8,9]. While over 50% of adult cigarette smokers attempt to quit each year, only 7.5% of cessation attempts succeed[10]. To aid in cessation efforts, contemporary approaches involve pharmacologic and behavioral support programs. Importantly, many medical centers require smoking cessation for a period before elective surgery to reduce perioperative complications. Thus, elective surgery has been suggested to be an effective and durable method for helping patients abstain from tobacco use[11].

The purpose of the present study was to better understand tobacco use patterns postoperatively after preoperative cessation efforts in patients undergoing elective TJA. Secondary goals were to evaluate postoperative patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and identify effective methods for assisting with cessation efforts. We hypothesize that tobacco cessation prior to elective TJA will lead to lasting abstinence postoperatively for many patients at a higher rate than those undergoing cessation for other reasons, as reported in the literature.

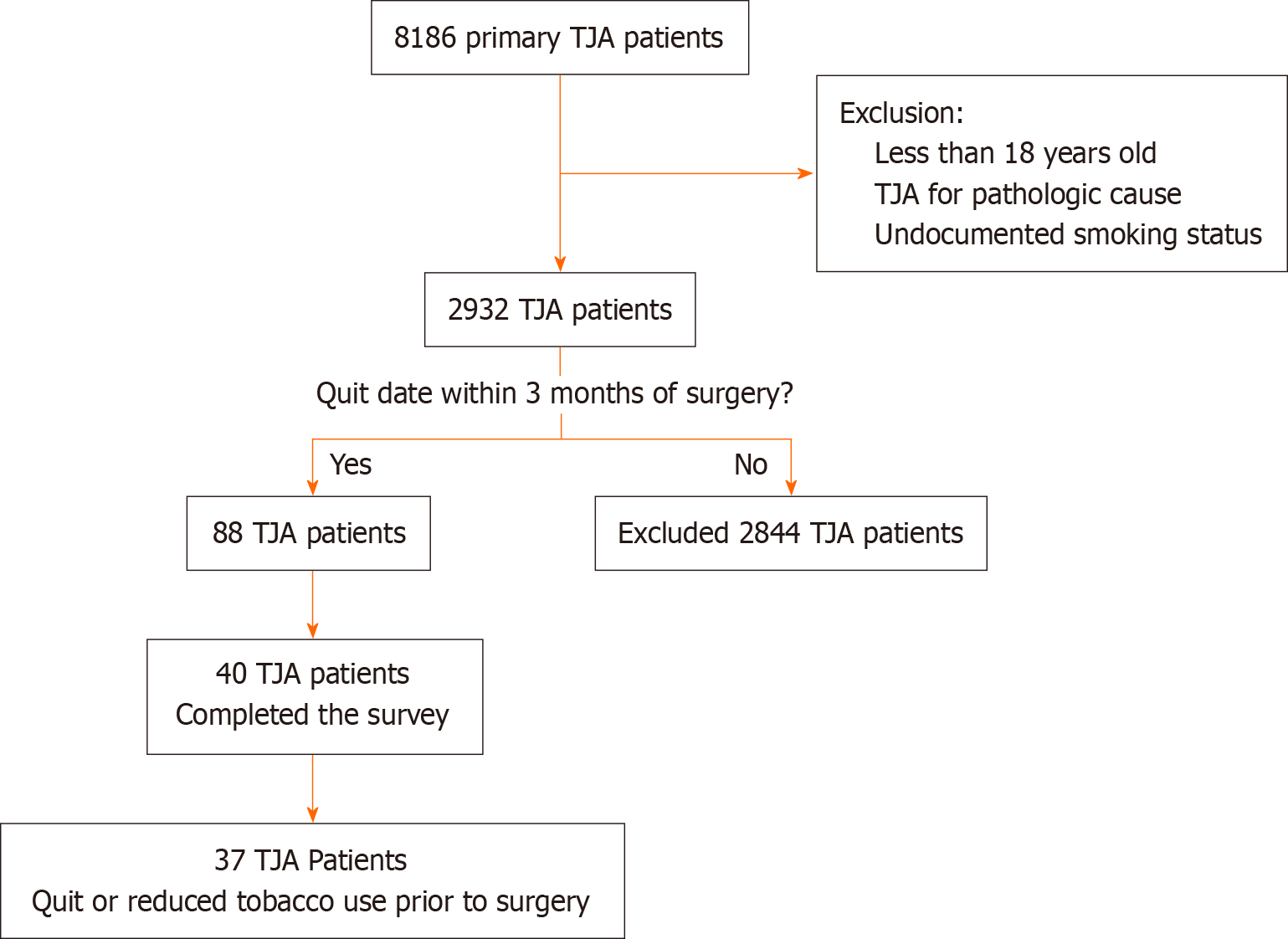

A retrospective review was undertaken for patients who underwent total hip and knee arthroplasty at a single tertiary referral center. The institutional electronic health record (EHR) database was queried for all primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) (n = 3499) and primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) (n = 4687) performed by one of five fellowship-trained arthroplasty surgeons between January 2014 and December 2022. Patients less than 18 years of age were excluded. Patients undergoing arthroplasty for fracture or oncologic condition were excluded. Self-reported smoking status (current, former, or never smoker) was available for 1682 TKA and 1250 THA patients. Of these, 33 TKA and 55 THA had cessation dates recorded in the EHR within 3 mo of their TJA, for a cohort of 88 patients. The EHR was used to confirm that all patients in our cohort were smokers prior to surgery and had documented correspondence with their surgeon’s team to either quit or cut back on tobacco use preoperatively.

Demographic information collected at the time of surgery included: age, race, sex, marital status, alcohol use, tobacco use, American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) grade, anesthesia type, body mass index (BMI), laterality, procedure details. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-10, and knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint replacement (KOOS. JR) or hip dysfunction and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint replacement (HOOS. JR).

Our patient cohort was prospectively contacted to participate in a phone survey (Supplementary material). The survey included questions regarding their tobacco use prior to and after surgery, cessation efforts, current smoking status, as well as PROMIS-10, HOOS. JR or KOOS. JR scores. Patient reported cessation interventions were recorded as free responses and subsequently categorized into no intervention, prescription medication (varenicline, bupropion), nicotine replacement, counseling, and gum or mints. Patients who did not have accurate contact information or who were not able to be reached after three attempts were excluded. Five patients were contacted and declined participation in the survey. A total of 37 TJA patients voluntarily participated and met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patient selection is illustrated in Figure 1.

Descriptive statistics were used to interpret the data. Univariable statistics were performed using t-tests or chi-square tests. Paired Wilcoxon tests were used to compare individuals’ tobacco use before and after surgery and Bonferroni corrections were applied. No a priori power analysis was performed based on study design evaluating a retrospective cohort of patients over a fixed period when smoking cessation was required who were prospectively contacted. Sensitivity analysis performed at a power of 0.8 and alpha of 0.05 for a one-tailed t-test demonstrated that the current study group sizes were sufficient to detect large effect size differences (P > 0.8). Statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Significance level was defined as P < 0.05. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

Our cohort was on average 60.62 ± 11.90-years-old, 59.5% (n = 22) female, 70.3% (n = 26) Caucasian, 56.8% (n = 21) married, with an average BMI of 29.96 kg/m2 ± 6.86 kg/m2. Average ASA score was 2.43 ± 0.55 and average length of hospital stay was 2.76 ± 1.92 d. There were no significant differences in demographic information between those that remained abstinent from tobacco and those that did not postoperatively. Basic demographic information can be seen in Table 1. The average time from surgery to completion of the survey was 2.85 ± 1.93 years.

| Parameter | Overall cohort | Relapsed postop | Abstinent postop | P value |

| Number of patients | 37 | 21 | 16 | |

| Total knee replacement | 17 (45.9) | 12 (57.1) | 5 (31.2) | 0.22 |

| Average age in yr (SD) | 60.62 (11.90) | 62.76 (12.32) | 57.81 (11.08) | 0.22 |

| Male | 15 (40.5) | 9 (42.9) | 6 (37.5) | 1.00 |

| Race | 0.62 | |||

| African American | 10 (27.0) | 5 (23.8) | 5 (31.2) | |

| Caucasian | 26 (70.3) | 15 (71.4) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Other | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.36 | |||

| Divorced | 6 (16.2) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Married | 21 (56.8) | 10 (47.6) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Single | 9 (24.3) | 5 (23.8) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Widowed | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Average BMI (SD) | 29.96 (6.86) | 30.53 (6.75) | 29.20 (7.17) | 0.58 |

| Average ASA (SD) | 2.43 (0.55) | 2.52 (0.60) | 2.31 (0.48) | 0.26 |

| Hospital LOS in d (SD) | 2.76 (1.92) | 2.90 (2.21) | 2.56 (1.50) | 0.6 |

| Follow up mean (SD) | 2.85 (1.93) | 2.65 (2.20) | 3.11 (1.53) | 0.48 |

Out of the 88 eligible patients, 40 (45.5%) were able to be contacted and volunteered to participate in our survey. A total of 37/40 patients confirmed that they were able to reduce or quit tobacco products prior to their elective TJA. All patients (n = 37) reported tobacco use within the year preceding their total joint replacement with 86.5% (n = 32) smoking cigarettes. A total of 83.8% (n = 31) of patients stated that they received a tobacco cessation request from their surgeon prior to their elective total joint surgery. 100% (n = 37) of patients reduced their tobacco use prior to surgery and 73.0% (n = 27) of patients maintained complete abstinence prior to their surgery.

There were various methods used to help abstain from tobacco use perioperatively. The most common method was “cold turkey” with 64.5% (n = 24) of patients not using any cessation aids. 13.5% (n = 5) of patients used prescription pharmacologic therapy, and 18.9% (n = 7) of patients used over the counter nicotine replacement therapy. Only two patients (5.4%) reported using a cessation program to help curb tobacco use perioperatively. At final follow up, 43.2% (n = 16) of prior tobacco smokers maintained complete abstinence. Those that relapsed did so at an average of 2.73 ± 1.82 mo after surgery. Tobacco use and cessation information is illustrated in Table 2.

| Parameter | Overall cohort | Relapsed postop | Abstinent postop | P value |

| Number of patients | 37 | 21 | 16 | |

| Tobacco use preoperatively | 0.66 | |||

| Cigarettes | 32 (86.5) | 18 (85.7) | 14 (87.5) | |

| Cigars | 4 (10.8) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Other | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Provider requested tobacco abstinence preoperatively | 0.34 | |||

| Yes | 31 (83.8) | 19 (90.5) | 12 (75.0) | |

| No | 5 (13.5) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Can't remember | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| PPD prior to cessation efforts (SD) | 0.74 (0.52) | 0.80 (0.55) | 0.68 (0.48) | 0.51 |

| Complete tobacco abstinence preoperatively | 27 (73.0) | 15 (71.4) | 12 (75.0) | 1.00 |

| PPD preoperatively after cessation efforts | 0.06 (0.12) | 0.08 (0.14) | 0.04 (0.10) | 0.49 |

| Time until tobacco relapse in mo (SD) | 2.73 (1.82) | 2.73 (1.82) | Not Applicable | |

| Cessation method | 0.55 | |||

| Nothing | 24 (64.9) | 12 (57.1) | 12 (75.0) | |

| Prescription medication | ||||

| Varenicline | 2 (5.4) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bupropion | 3 (8.1) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Nicotine replacement | 7 (18.9) | 6 (28.6) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Counseling | 2 (5.4) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gum or mints | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Current tobacco use | 19 (51.4) | 19 (90.5) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.01 |

| Tobacco use at some point postoperatively | 2 (5.4) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.59 |

| Average PPD (SD) | 0.24 (0.35) | 0.44 (0.37) | 0.00 (0.00) | < 0.01 |

| Reported complication postoperatively | 0.36 | |||

| SSI | 1(2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Dislocation | 1(2.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PJI | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Revision surgery | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

PROMIS-10 physical and mental health scores were collected along with KOOS. JR for TKAs and HOOS. JR for THAs. Overall, PROMIS-10 mental health scores were significantly higher in those that were able to maintain cessation long-term at the distribution of this survey (48.58 vs 57.79; P < 0.01). KOOS. JR were also significantly improved in those that maintained tobacco cessation (63.12 vs 82.05; P = 0.02). Although both the PROMIS-10 physical function score and the KOOS. JR scores were improved with tobacco abstinence at time of the survey, these did not reach statistical significance at P = 0.09 and P = 0.40, respectively. Patient reported outcomes are documented in Table 3.

| Outcome score | Overall cohort | Relapsed postop | Abstinent postop | P value |

| Number of patients | 37 | 21 | 16 | |

| Promis-10 physical function score, Mean (SD) | 46.35 (9.25) | 44.12 (9.52) | 49.27 (8.27) | 0.09 |

| Promis-10 mental health score, Mean (SD) | 52.56 (10.60) | 48.58 (11.65) | 57.79 (6.12) | < 0.01 |

| KOOS. JR, Mean (SD) | 80.77 (17.58) | 78.36 (19.88) | 86.56 (9.52) | 0.4 |

| HOOS. JR, Mean (SD) | 73.53 (18.02) | 63.12 (8.23) | 82.05 (19.63) | 0.02 |

Complications related to the TJA were collected. There was one superficial surgical site infection (SSI) that was treated with oral antibiotics. There was one hip dislocation after a fall that required a sedated closed reduction at an outside facility without subsequent dislocations. None of the patients in this cohort had a PJI or required revision surgery on their TJA.

Smoking tobacco perioperatively is a modifiable risk factor for surgical complications with associated increased cost of care[3,4,9-11]. In TJA patients, cessation from tobacco use preoperatively has been shown to improve postoperative outcomes and reduce the risk of wound complications and PJI[8,9]. Cessation programs and pharmacologic agents can help with these efforts and have been shown to be efficacious and cost effective[12]. Prior investigations have shown that cessation attempts in the perioperative period can substantially increase success rates in active tobacco users[13].

In our study, 73.0% of patients were able to quit tobacco use prior to surgery, and 43.2% of patients reported continued abstinence at an average follow up of 3.11 years postoperatively. It is estimated that only 7.5% of all tobacco cessation attempts are successful in the general population[10]. However, the present study notes a cessation rate that was nearly six-times higher. This is in line with other studies reporting a high rate of successful tobacco cessation surrounding elective TJA. Smith et al[11] reported on 23 patients who underwent lower extremity orthopedic surgery and found that 48% of patients maintained smoking abstinence for at least 1 year postoperatively. Hall et al[14] surveyed 124 patients undergoing TJA and found that 23% of patients never resumed smoking at an average follow up of 52 (range 15-126) mo[14]. Perioperative care and timing surgery around smoking cessation provides clinicians with a unique opportunity to assist active tobacco smokers with durable cessation effects.

In our study, methods used to quit or cut back on tobacco use included nicotine replacement, prescription medications, and cessation programs. Most patients reported using no cessation aids. There is a cessation program available at our institution, however this was not commonly utilized by patients. There is evidence to suggest that offering smoking interventions, behavioral support, and nicotine replacement therapy are effective at increasing the likelihood of perioperative abstinence, limiting relapse, and reducing postoperative morbidity[13]. This suggests that even higher rates of long-term tobacco abstinence could have been achieved with initiatives or standardized programs for these patients. Targeted therapeutic interventions could provide a secondary benefit of helping prevent relapse postoperatively in active tobacco users.

Preoperative patient reported outcome scores including PROMIS-10, HOOS. JR and KOOS. JR were incomplete and could not be reported. Postoperative PROs showed a statistically significant improvement in PROMIS-10 global mental health scores in patients who maintained cessation until the time of the survey. Additionally, HOOS. JR scores were significantly improved in patients who had a THA and maintained smoking cessation until final follow up. The PROMIS mental health score has not been shown to be independently predictive of postoperative achievement of minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in TJA patients[15]. The MCID for HOOS. JR using an anchor-based approach has been calculated to be 18 points[16]. There was an 18.9-point improvement in HOOS. JR scores in THA patients who were able to maintain tobacco abstinence postoperatively compared to those that resumed tobacco use, suggesting a significant clinical improvement. Aside from the numerous health benefits that can be achieved with tobacco cessation, there is potential for improvements in TJA outcomes with continued smoking abstinence postoperatively as demonstrated here. We suggest that clinicians should focus equal effort in limiting tobacco use postoperatively as they do preoperatively.

Patients who relapsed postoperatively did so early, at an average of less than 3 mo postoperatively. From a public health perspective, efforts should focus on maintaining smoking cessation in patients in this perioperative period to prevent relapse. Gilpin et al[17] reported that there was a lower relapse rate in patients who remained continuously abstinent for longer periods of time. Overall, they showed that the probability of remaining continuously abstinent until final follow-up was around 90% for former smokers who had quit for 3 mo or longer and 95% for those who had quit for 1 year or longer. Concerted efforts by providers and patients in the perioperative period may lead to higher rates of successful cessation long-term.

The limitations of this study are well-recognized. Our study sample is limited by the small number of patients included, limited geographic region, and accuracy and availability of information in the EHR, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. We only reported on patients who had documented smoking status in their record, which confined us to only 35% of the TJA patients and may underestimate the true prevalence of tobacco use within our TJA patient population. Laboratory testing for nicotine in patients is not routine at our institution, and this study relied on patient-reported tobacco use habits. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of patient interviews allows for potential confounding factors through recall and response bias. Despite this, self-reported smoking status has been validated in orthopedic patients compared to objective cotinine measurements[18]. There were five patients who we were able to contact but who declined participation in our survey. Along with this, a large percentage of patients had inaccurate contact information or could not be reached by phone call, which also introduces potential bias into our study. Finally, the present study did not include a control group of patients without preoperative tobacco cessation efforts, limiting the attributability of differences in postoperative outcomes on successful cessation alone. Future studies with larger sample sizes, prospective designs, and inclusion of control groups are warranted to validate the efficacy of preoperative tobacco cessation interventions in the TJA population.

Despite these limitations, the present study showed that patients undergoing TJA who were able to remain abstinent from tobacco products postoperatively had improved PROMIS-10 mental health scores and HOOS. JR with effect sizes large enough to be detected at the present sample sizes. Forty three percent of patients in our cohort reported continued abstinence at an average follow up of nearly 3 years postoperatively. This equates to a nearly six-times higher tobacco cessation rate seen perioperatively compared to attempts made by the general population[10]. Requiring tobacco cessation prior to elective arthroplasty can help patients effectively obtain and maintain tobacco abstinence. This highlights an important opportunity for patients and providers to make concerted efforts towards tobacco cessation to positively impact patient outcomes.

Tobacco use is a well-documented modifiable risk factor for many negative outcomes in orthopedic surgery including higher rates of wound complications and infection. Many institutions encourage tobacco cessation prior to elective surgery. It is estimated that only 7.5% of all tobacco cessation attempts are successful. Reports suggest higher rates of abstinence can be achieved surrounding elective surgery[11,14]. Here, we report a cessation rate of 43.2% in patients undergoing elective TJA. Most of these patients did not use cessation aids for assistance. Patients undergoing TJA who were able to remain abstinent from tobacco products postoperatively had improved PROMIS-10 mental health scores and HOOS. JR scores. The perioperative period provides clinicians a unique opportunity to assist active tobacco smokers with durable cessation efforts.

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use Fast Facts. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index. |

| 2. | American Cancer Society. Health Risks of Smoking Tobacco. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/healthy/stay-away-from-tobacco/health-risks-of-tobacco/health-risks-of-smoking-tobacco. |

| 3. | Castillo RC, Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Patterson BM; LEAP Study Group. Impact of smoking on fracture healing and risk of complications in limb-threatening open tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peng XQ, Sun CG, Fei ZG, Zhou QJ. Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infection After Spinal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on Twenty-Seven Studies. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:e318-e329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wiewiorski M, Barg A, Hoerterer H, Voellmy T, Henninger HB, Valderrabano V. Risk factors for wound complications in patients after elective orthopedic foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:479-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cho BH, Aziz KT, Giladi AM. The Impact of Smoking on Early Postoperative Complications in Hand Surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2021;46:336.e1-336.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hatta T, Werthel JD, Wagner ER, Itoi E, Steinmann SP, Cofield RH, Sperling JW. Effect of smoking on complications following primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bedard NA, DeMik DE, Owens JM, Glass NA, DeBerg J, Callaghan JJ. Tobacco Use and Risk of Wound Complications and Periprosthetic Joint Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty Procedures. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Herrero C, Tang A, Wasterlain A, Sherman S, Bosco J, Lajam C, Schwarzkopf R, Slover J. Smoking cessation correlates with a decrease in infection rates following total joint arthroplasty. J Orthop. 2020;21:390-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, Cullen KA, Day H, Willis G, Jamal A, Neff L. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 696] [Article Influence: 116.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Smith DH, McTague MF, Weaver MJ, Smith JT. Durability of Smoking Cessation for Elective Lower Extremity Orthopaedic Surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27:613-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Boylan MR, Bosco JA 3rd, Slover JD. Cost-Effectiveness of Preoperative Smoking Cessation Interventions in Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thomsen T, Villebro N, Møller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD002294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hall JRL, Metcalf R, Leisinger E, An Q, Bedard NA, Brown TS. Does Smoking Cessation Prior to Elective Total Joint Arthroplasty Result in Continued Abstinence? Iowa Orthop J. 2021;41:141-144. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Darrith B, Khalil LS, Franovic S, Bazydlo M, Weir RM, Banka TR, Davis JJ. Preoperative Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health Scores Predict Patients Achieving the Minimal Clinically Important Difference in the Early Postoperative Time Period After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e1417-e1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lyman S, Lee YY, McLawhorn AS, Islam W, MacLean CH. What Are the Minimal and Substantial Improvements in the HOOS and KOOS and JR Versions After Total Joint Replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:2432-2441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Farkas AJ. Duration of smoking abstinence and success in quitting. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:572-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bender D, Haubruck P, Boxriker S, Korff S, Schmidmaier G, Moghaddam A. Validity of subjective smoking status in orthopedic patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:1297-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |