Published online Oct 18, 2023. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v14.i10.755

Peer-review started: January 3, 2023

First decision: April 13, 2023

Revised: April 26, 2023

Accepted: June 9, 2023

Article in press: June 9, 2023

Published online: October 18, 2023

Processing time: 285 Days and 16.4 Hours

Flexible flatfoot (FFF) is a very common condition in children, but no evidence-based guidelines or assessment tools exist. Yet, surgical indication is left to the surgeon’s experience and preferences.

To develop a functional clinical score for FFF [Catania flatfoot (CTF) score] and a measure of internal consistency; to evaluate inter-observer and intra-observer reliability of the CTF Score; to provide a strong tool for proper FFF surgical indication.

CTF is a medically compiled score of four main domains for a total of twelve items: Patient features, Pain, Clinical Parameters, and Functionality. Each item refers to a specific rate. Five experienced observers answered 10 case reports according to the CTF. To assess inter- and intra-observer reliability of the CTF score, the intra-class correlation coefficients’ (ICCs) statistics test was performed, as well as to gauge the correlation between the CTF score and the surgical or conservative treatment indication. Values of 75% were chosen as the score cut-off for surgical indication. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLHR), negative likelihood ratio (NLHR), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

Overall interobserver reliability ICC was 0.87 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.846-0.892; P < 0.001]. Overall intra-observer reliability ICC was 0.883 (95%CI: 0.854-0.909; P < 0.001). A direct correlation between the CTF score and surgical treatment indication [Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.94 (P < 0.001)] was found. According to the 75% cut-off, the sensitivity was 100% (95%CI: 83.43%-100%), specificity was 85.71% (95%CI: 75.29%-92.93%), PLHR was 7 (95%CI: 3.94-12.43), NLHR was 0 (95%CI: 0-0), PPV was 75% (95%CI: 62.83%-84.19%) and NPV was 100% (95%CI: 100%-100%).

CTF represents a useful tool for orthopedic surgeons in the FFF evaluation. The CTF score is a quality questionnaire to reproduce suitable clinical research, survey studies, and clinical practice. Moreover, the 75% cut-off is an important threshold for surgical indication and helps in the decision-making process.

Core Tip: There was no validated children’s flexible flatfoot questionnaire in the literature. Catania flatfoot is a medical score of four main domains for a total of twelve items: Patient features, pain, clinical parameters, and functionality. The tool was easy to perform and reproduce in clinical research, survey studies, or clinical practice. The 75% cut-off is an important threshold for surgical indication and help in the decision-making process.

- Citation: Vescio A, Testa G, Caldaci A, Sapienza M, Pavone V. Catania flatfoot score: A diagnostic-therapeutic evaluation tool in children. World J Orthop 2023; 14(10): 755-762

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v14/i10/755.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v14.i10.755

The flexible flatfoot (FFF), known as pes planus, is a very common condition in children characterized by loss of the medial arch and an increase in the support base along with valgus of the hindfoot, yet 40 different definitions were formulated[1]. FFF is associated with anatomical conditions, including valgus heel, subluxation of the subtalar joint with intra-rotation of the talus and flexion of plantar abduction of the mid-tarsal joint with naval dorsal subluxation[2]. Generally, FFF is an age-related physiological variant, not a disease, and its incidence decreases significantly in terms of increased age: In children 3-years-old, it is 54%, whereas in children 6-years-old, it is 24%[3]. A history should include pain, location, intensity, functional problems, while trauma or recurrent ankle sprains should be specifically questioned. FFF is typically an asymptomatic condition[4]. Lower limb pain[5] and lower limb function[6] were found as the main manifestations in symptomatic FFF. Until 2022, more than 300 scientific articles were published, without evidence-based guidelines. The challenge for health professionals is to identify when a child’s foot is consistent with developmental expectations, particularly in relation to foot posture, and/or function to reassure, monitor or intervene accordingly[7-10]. Therefore, the measure to indicate where foot posture is outside of expected flatness in children (i.e., the diagnoses of flat foot) must be valid, reliable, and appropriate for developing foot posture typically observed. Recently, a systematic review[1] highlighted there was no consistency used to determine pediatric FFF in the literature or the choice of foot posture measures, in relation to validity and reliability, which was rarely justified. A surgical indication was in effect for the surgeon’s experience[11,12]. The purpose of the study was to develop new functional clinical scores for FFF to assess toddlers and adolescent patients’ characteristic functionality [Catania flatfoot (CTF] Score) and measure of internal consistency; to evaluate inter- and intra-observer reliability of the CTF Score; and to provide a reliable tool for proper FFF surgical indication.

The CTF Score development was composed of two parts, the CTF Score Conception and CTF Score Composition and Scoring.

CTF score conception: An orthopedic team was involved in developing the questionnaire. The CTF score was designed to be used in different clinical settings, including clinical research, survey studies, and clinical practice to assess FFF-affected patients and possibly assess changes with treatment. The development team was composed of two senior orthopedic and trauma surgeons (Vito Pavone and Gianluca Testa), and one pediatric orthopedic (fully-trained) resident (Andrea Vescio). At an early stage, an author (Andrea Vescio) search was done to analyze the functional foot and ankle score previously described and developed as the CTF score. Senior authors (Vito Pavone and Gianluca Testa) reviewed and validated the scores.

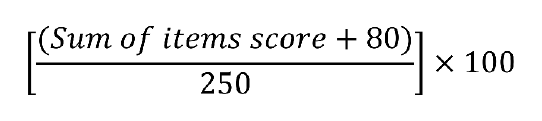

CTF score composition and scoring: The questionnaire is a medically-compiled score of four main domains for a total of twelve items: Patient features (2 items), pain (1 item), clinical parameters (5 items), and functionality (4 items). Each item refers to a specific rate as reported in Supplementary Table 1. The lowest achievable value is -80, while the highest is 170. Calculation of the CTF score is based on the following formula:

The value is expressed as a percentage: Higher percentages are associated with a lower clinical presentation.

CTF score patient features domain: Patient features are composed of two items aimed to assess the principal general parameters of the evaluated subject. The first item is related to age; the second is linked to laxity. Hypermobility can be assessed according to the passive dorsiflexion of the fifth hand finger and thumbs, elbow, and knee hyperextension.

CTF score pain domain: The pain domain was composed of one item to assess generalized pain of the foot or ankle, as well as in the plantar arch, heel, tibialis posterior tendon, and fascia.

CTF score clinical parameters domain: The clinical parameters domain is composed of five items to assess the callous present, valgus of hindfoot, longitudinal arch, forefoot abduction, and triceps contracture. For each item, three answers are admissible: “none”, “mild”, and “severe”. The first item “callous” allows for two answers: “yes” and “no”.

CTF score functionality domain: The functionality domain provides four items to evaluate the patient’s capacities. Fatigue, inadequate physical and sport performance, and wear of orthosis is recorded. The first and last items of the section (“fatigue” and “orthosis”) allow for two answers: “yes” and “no”, while others provide “none”, “mild”, and “severe”.

A review of all infants, toddlers, and adolescents admitted through the pediatric orthopedic ambulatory were carried out. For each patient the following demographic and clinical data captured: Gender, age, the involved side, and presence or absence of associated syndromes or deformities, past and recent medical history for foot and ankle discomfort or pain. Frontal, lateral, and posterior view photos were taken. The pictures were performed in the same positions to provide the more possible objectivity and recorded in an online database. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Chronological age 17-years-old; (2) physical and podoscopic examination; (3) complete photographic history; and (4) positive Tip Toe and Jack test; all cases were examined by the same expected pediatric orthopedic team.

Children in the study were independently examined and assessed by two orthopedic surgeons and three residents in pediatric orthopedics: All evaluators had previous experience of at least twenty-four months. Three assessors, two surgeons, and a resident completed a full program while treating over 50 FFF patients in the previous two years. All observers had 1 h of theoretical FFF clinical manifestation and score system training before patients’ assessment. Each contributor was provided with a summary of the medical history and clinical examination of the frontal, lateral, and posterior view photos. As per the web-based score, observers were asked about conservative or surgical indication. Answers were submitted via a link hosted by https://www.google.com/ forms and recorded by an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States). The CTF score was submitted at two different points.

To assess the inter- and intra-observer reliability of the CTF score, the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) statistics test was performed. For scale development, it is generally accepted there should be at least five times the number of respondents as questions, for at least 60 in total[11].

To assess the correlation between the CTF score and surgical or conservative treatment, values of 75% were used as a score cut-off for surgery. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLHR), negative likelihood ratio (NLHR), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were used.

Continuous data are presented as the mean and standard deviation when appropriate. The ICC (two-way random effects model, with single-measure reliability) was performed to evaluate intra- and interobservers’ agreement. According to the Koo and Li guideline, agreement below 0.50 was considered “poor”; between 0.50 and 0.74 as “moderate”; between 0.75 and 0.89 as “good”; and above 0.90 as “excellent”[12]. The Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) was utilized to assess the correlation between conservative or surgical treatment and the CTF score. PCC vales between -1 and 1, where values close to -1 indicated high negative correlation, with values close to 1 indicating a high positive correlation, and values close to 0 indicating no or a very week correlation.

A rule of thumb for interpreting the coefficient is provided by Colton et al[13]: (1) 0 to 0.25 (0 to -0.25) little or no relationship; (2) 0.25 to 0.50 (-0.25 to -0.50) fair degree of a relationship; (3) 0.50 to 0.75 (-0.50 to -0.75) moderate to good degree of a relationship; and (4) 0.75 to 1.00 (-0.75 to -1.00) very good to excellent relationship.

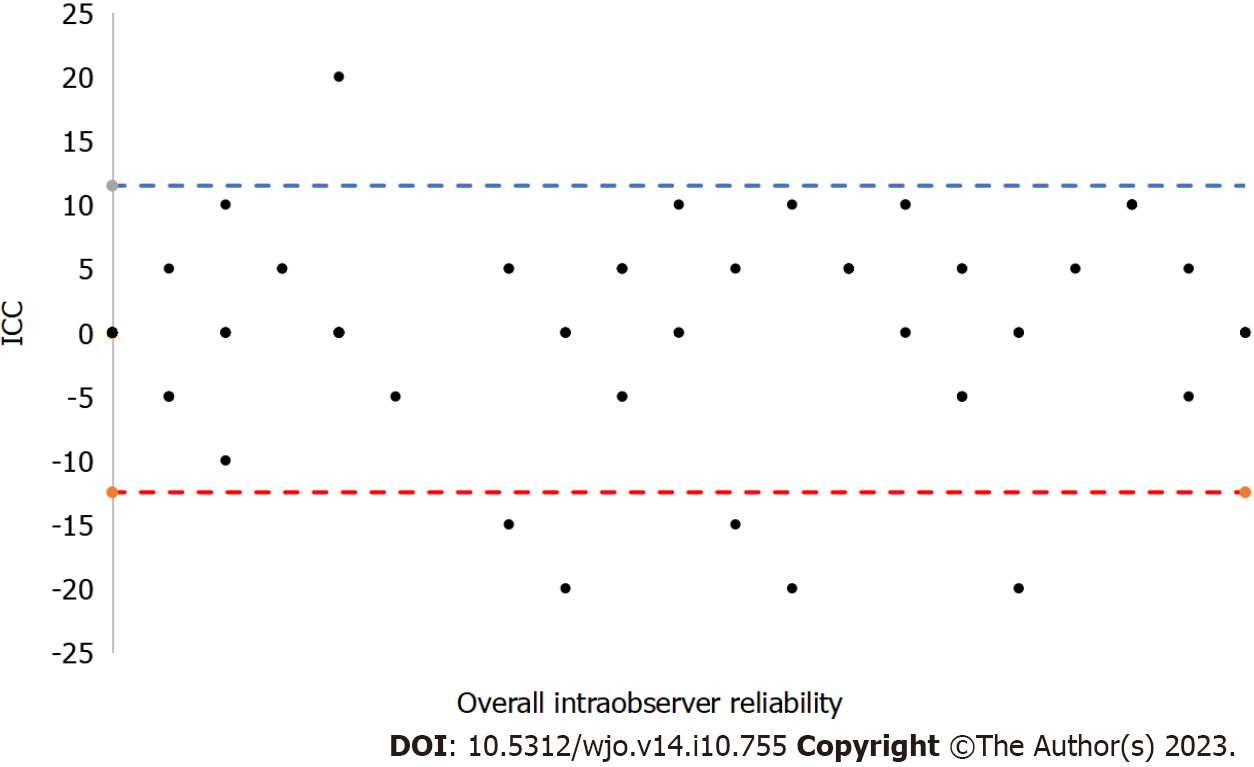

The Bland and Altman plot was produced to analyze differences between cohort measurements. The limits of agreement were calculated as the mean difference ± 1.96 SD[14]. A value of 75% was chosen as a score cut-off for surgical indication. Sensitivity, specificity, PLHR, NLHR, PPV, and NPV were recorded. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, Version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

Five different experienced observers answered 10 case reports. For each patient, observers responded to 14 questions (12 items and 2 treatment indications) for a total of 140 responses. The web-based survey was submitted at two different times, while 280 observations were reported.

Overall interobserver reliability ICC was 0.87 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.846-0.892; P < 0.001; “good”]. The ICC value for specialists was 0.809 (95%CI: 0.761-0.849; P < 0.001; “good”), but was 0.852 (95%CI: 0.821-0879; P < 0.001; “good”) for residents (Table 1).

| Sample | ICC | 95% confidence interval | Value | P value | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Overall | 0.883 | 0.854 | 0.909 | 7.513 | < 0.0001 |

| Specialists | 0.869 | 0.832 | 0.901 | 27.523 | < 0.0001 |

| Residents | 0.878 | 0.846 | 0.907 | 44.351 | < 0.0001 |

The overall intra-observer reliability ICC was 0.883 (95%CI: 0.854-0.909; P < 0.001) and considered “good” (Table 2 and Figure 1).

| Sample | ICC | 95% confidence winterval | Value | P value | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Overall | 0.870 | 0.846 | 0.892 | 34.479 | < 0.0001 |

| Specialists | 0.809 | 0.761 | 0.849 | 9.475 | < 0.0001 |

| Residents | 0.852 | 0.821 | 0.879 | 18.272 | < 0.0001 |

The ICC value for specialists was 0.869 (95%CI: 0.832-0.901; P < 0.001; “good”), but was 0.878 (95%CI: 0.846-0.907; P < 0.001; “good”) for residents (Table 1).

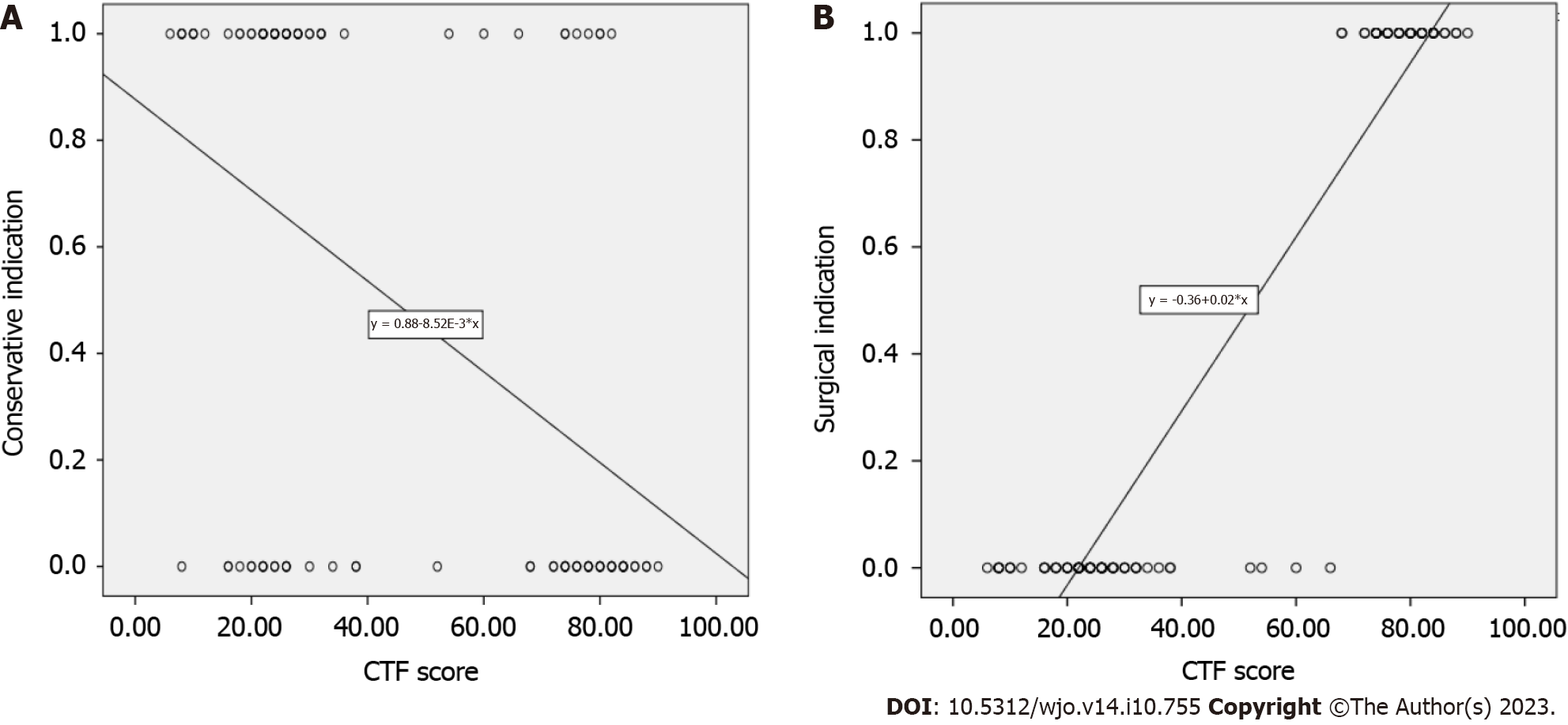

A fair inverse correlation occurred between the CTF score and conservative treatment indication (PCC = -0.483; P < 0.001) (Figure 2A).

The direct correlation between the CTF score and surgical treatment indication (PCC = 0.94; P < 0.001) was rated “from good to excellent” (Figure 2B).

According to the 75% cut-off, sensitivity was 100% (95%CI: 83.43%-100%), specificity was 85.71% (95%CI: 75.29%-92.93%), PLHR was 7 (95%CI: 3.94-12.43), NLHR was 0 (95%CI: 0-0), PPV was 75% (95%CI: 62.83%-84.19%), and NPV was 100% (95%CI: 100%-100%).

The CTF score was found to be a valid, effective tool in flatfoot assessment. The scale was seen as good or excellent for inter- and intra-observer reliability, done independently with experience levels. Higher score values were directly correlated with surgical treatment needs, while an increase in score reduced conservative management indication. In addition, the 75% CTF score values were discovered as reasonable cut-off points for surgical treatment, while high percentages of sensitivity and specificity guaranteed safe tool utilization.

In recent surveys, European[9] and Italian[10] pediatric orthopedics underlined the absence of a specific and universally-recognized clinical evaluation score for juvenile FFF. The CTF Score fills the literature void and, considering the good results, can be proposed as a helpful tool for clinical research, survey studies, and clinical practice to assess FFF-affected patients as well as changes with treatment.

Each domain scale was developed according to the weighted preferences of European and Italian pediatric orthopedics which ensure that each scale is internally consistent, i.e., measures a single trait and that each item has different levels of difficulty or severity.

The final instrument comprises 12 questions divided into four domains which measure problems in domains titled Patient features (2 items), pain (1 item), clinical parameters (5 items), and functionality (4 items). Raw domain scores can be transformed into percentage scores to make them easier to interpret; higher scores indicate more severe disability. The item has strong face validity and is included as a categorical descriptive variable but not allied to any domain scale. The instrument is not suitable for those who are unable to walk, or who have a significant proximal component to their disability.

In 2005, the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) members identified the Foot Function Index, and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Foot and Ankle module scores as the most frequently used in the literature[15]. Yet, AOFAS[16], Foot and Ankle Ability Measure[17], and the Rowan Foot Pain Assessment Questionnaire[18] were commonly utilized for foot and ankle disorder evaluation. On the other hand, previous scores were not specific for children or flatfoot, because they were developed for adult generalized foot and ankle disease or ankle osteoarthritis.

The Oxford Ankle Foot Questionnaire for Children (OxAFQ-C) is the only validated tool in the pediatric population to measure the subjective well-being of children from 5- to 16-years-old with foot and ankle conditions[19]. The major limit of the OxAFQ-C is its patient-reported nature, as several studies report a tendency in children to score themselves higher than their parents[20,21], while the physician CTF Score report an intra-observer reliability of 0.883, with the OxAFQ-C domain reliability rating at 0.6 and 0.83. In addition, the tool was useful for physicians with an intra- and interobserver reliability of 0.852 and 0.878, respectively.

Since March 2020, the pandemic emergency raised questions about alternatives to normal clinical activity to avoid overcrowding in departments; for less risk of contagions, many checkups were procrastinated. This issue caused a possible loss of patient follow-up, which can reflect on the clinic and its outcomes. The necessity to develop management protocols highlights telemedicine as a valid alternative in particular conditions vs the face-to-face clinic, with safety margins and economic savings. The CTF score was administered with a web-based database, well-tolerated by observers; moreover, despite assessment of foot functionality, the CTF Score does not include a range of motion evaluation. The score was considered a good remote follow-up tool. The authors intend to promote the distribution of the score and face-to-face and remote validation.

Surgical treatment is still debated, as Bouchard and Mosca[22] suggested that surgical management be used only in Achilles’ tendon retraction, while several authors highlighted issues of fatigue, inadequate physical performance, and pain as the main parameters for the decision-making process[23]. The 75% CTF score cut-off presented high sensitivity and specificity as reasonable cut-offs for surgical treatment. The tool does not replace the surgeon’s experience, but represents a helpful orthopedic decision-making process. The CTF provides to general or pediatric physicians, podiatrist, physiotherapists, young or non-pediatric orthopedic trained orthopedic surgeons a common accepted and objective additional tool for the correct flatfoot grade and eventually surgical indication. The patient and family history, body posture assessment remain mandatory for the proper assessment. Future research into the development and validation of the questionnaire will assess whether the instrument is responsive to change. We will administer the questionnaire to general non-pediatric orthopedic surgeons, and reassess test-retest reliability while monitoring dimensionality and scaling of the instrument as more data become available.

The limits of the score are related to the domains compilation, in fact, the valgus of the hindfoot, longitudinal arch, forefoot abduction, and triceps contracture assessment are related to the physician or surgeon experience, and the fatigue, inadequate physical and sport performance items are related to the patient consciousness. In the future, the development of new and more objective criteria could make the CTF more usable.

In conclusion, the CTF Score is useful for orthopedic surgeons in the juvenile FFF evaluation. The CTF score is derived from a high-quality questionnaire for clinical research, survey studies, or clinical practice. The 75% cut-off point is a good threshold for surgical indication and decision-making. Given widespread use of telemedicine, the CTF score is also seen as an objective remote clinical examination.

Flexible flatfoot (FFF) is a very common condition in children, but no evidence-based guidelines or assessment tools exist. Yet, surgical indication is left to the surgeon’s experience and preferences.

The lack of common diagnostic criteria for FFF.

To develop a functional clinical score for FFF [Catania flatfoot (CTF) score] and a measure of internal consistency; to evaluate interobserver and intra-observer reliability of the CTF Score; to provide a strong tool for proper FFF surgical indication.

CTF is a medically compiled score of four main domains for a total of twelve items: Patient features, Pain, Clinical Parameters, and Functionality. Each item refers to a specific rate. Five experienced observers answered 10 case reports according to the CTF. To assess inter- and intra-observer reliability of the CTF score, the intra-class correlation coefficients’ (ICCs) statistics test was performed, as well as to gauge the correlation between the CTF score and the surgical or conservative treatment indication. Values of 75% were chosen as the score cut-off for surgical indication. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLHR), negative likelihood ratio (NLHR), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

Overall interobserver reliability ICC was 0.87 (95%CI: 0.846-0.892; P < 0.001). Overall intra-observer reliability ICC was 0.883 (95%CI: 0.854-0.909; P < 0.001). A direct correlation between the CTF score and surgical treatment indication [Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.94 (P < 0.001)] was found. According to the 75% cut-off, the sensitivity was 100% (95%CI: 83.43%-100%), specificity was 85.71% (95%CI: 75.29%-92.93%), PLHR was 7 (95%CI: 3.94-12.43), NLHR was 0 (95%CI: 0-0), PPV was 75% (95%CI: 62.83%-84.19%) and NPV was 100% (95%CI: 100%-100%).

CTF represents a useful tool for orthopedic surgeons in the FFF evaluation. The CTF score is a quality questionnaire to reproduce suitable clinical research, survey studies, and clinical practice. Moreover, the 75% cut-off is an important threshold for surgical indication and helps in the decision-making process.

CTF needs further multicentric studies to increase its validity for diagnostic and surgical indications in FFF.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jankowicz-Szymanska A, Poland; Vimal AK, India S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Banwell HA, Paris ME, Mackintosh S, Williams CM. Paediatric flexible flat foot: how are we measuring it and are we getting it right? A systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2018;11:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vescio A, Testa G, Amico M, Lizzio C, Sapienza M, Pavone P, Pavone V. Arthroereisis in juvenile flexible flatfoot: Which device should we implant? A systematic review of literature published in the last 5 years. World J Orthop. 2021;12:433-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Pfeiffer M, Kotz R, Ledl T, Hauser G, Sluga M. Prevalence of flat foot in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Halabchi F, Mazaheri R, Mirshahi M, Abbasian L. Pediatric flexible flatfoot; clinical aspects and algorithmic approach. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:247-260. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lin CJ, Lai KA, Kuan TS, Chou YL. Correlating factors and clinical significance of flexible flatfoot in preschool children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:378-382. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kosashvili Y, Fridman T, Backstein D, Safir O, Bar Ziv Y. The correlation between pes planus and anterior knee or intermittent low back pain. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:910-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Labovitz JM. The algorithmic approach to pediatric flexible pes planovalgus. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2006;23:57-76, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Evans AM. The flat-footed child -- to treat or not to treat: what is the clinician to do? J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:386-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pavone V, Testa G, Vescio A, Wirth T, Andreacchio A, Accadbled F, Canavese F. Diagnosis and treatment of flexible flatfoot: results of 2019 flexible flatfoot survey from the European Paediatric Orthopedic Society. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2021;30:450-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pavone V, Vescio A, Andreacchio A, Memeo A, Gigante C, Lucenti L, Farsetti P, Canavese F, Moretti B, Testa G, De Pellegrin M. Results of the Italian Pediatric Orthopedics Society juvenile flexible flatfoot survey: diagnosis and treatment options. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2022;31:e17-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mejabi J, Esan O, Adegbehingbe O, Orimolade A, Asuquo J, Badmus H, Anipole O, Anand A, Bin H, Razak A. The Pirani Scoring System is Effective in Assessing Severity and Monitoring Treatment of Clubfeet in Children. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;17:1-9. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Colton T, Johnson T, Machin D. Statistics in Medicine. In: Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2006. |

| 14. | Altman DG, Bland JM. Assessing Agreement between Methods of Measurement. Clin Chem. 2017;63:1653-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lau JT, Mahomed NM, Schon LC. Results of an Internet survey determining the most frequently used ankle scores by AOFAS members. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leigheb M, Janicka P, Andorno S, Marcuzzi A, Magnani C, Grassi F. Italian translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the "American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society's (AOFAS) ankle-hindfoot scale". Acta Biomed. 2016;87:38-45. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Martin RL, Irrgang JJ, Burdett RG, Conti SF, Van Swearingen JM. Evidence of validity for the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM). Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:968-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 622] [Cited by in RCA: 735] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rowan K. The development and validation of a multi-dimensional measure of chronic foot pain: the ROwan Foot Pain Assessment Questionnaire (ROFPAQ). Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:795-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morris C, Doll HA, Wainwright A, Theologis T, Fitzpatrick R. The Oxford ankle foot questionnaire for children: scaling, reliability and validity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1451-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ennett ST, DeVellis BM, Earp JA, Kredich D, Warren RW, Wilhelm CL. Disease experience and psychosocial adjustment in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: children's vs mothers' reports. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cronin CA. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Children: the Development of the TACQOL Parent Form. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2000;24:161. |

| 22. | Bouchard M, Mosca VS. Flatfoot deformity in children and adolescents: surgical indications and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:623-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | De Pellegrin M, Moharamzadeh D, Strobl WM, Biedermann R, Tschauner C, Wirth T. Subtalar extra-articular screw arthroereisis (SESA) for the treatment of flexible flatfoot in children. J Child Orthop. 2014;8:479-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |