Published online Sep 18, 2022. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v13.i9.870

Peer-review started: July 11, 2022

First decision: August 1, 2022

Revised: August 7, 2022

Accepted: August 25, 2022

Article in press: August 25, 2022

Published online: September 18, 2022

Processing time: 66 Days and 13.4 Hours

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD), or pseudogout, is an inflammatory arthritis common among elderly patients, but rarely seen in patients under the age of 40. In the rare cases presented of young patients with CPPD, genetic predisposition or related metabolic conditions were almost always identified.

The authors report the case of a 9-year-old boy with no past medical history who presented with acute knee pain and swelling after a cat scratch injury 5 d prior. Synovial fluid analysis identified calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals. Further MRI analysis identified osteomyelitis and a small soft tissue abscess.

This case presents the extremely rare diagnostic finding of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals in a previously healthy pediatric patient. The presence of osteomyelitis presents a unique insight into the pathogenesis of these crystals in pediatric patients. More research needs to be done on the role of CPPD in pedia

Core Tip: Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD) is rarely seen in patients under the age of 40. This case represents a rare diagnostic finding of CPP crystals in a 9-year-old patient. Previously, the youngest patients ever described in case reports were 16 years old. In the rare cases presented of young patients with CPPD, genetic predisposition or related metabolic conditions were almost always identified. In this case, the presence of osteomyelitis presents a unique insight into the pathogenesis of these crystals in pediatric patients. This case highlights the need for more research on the pathogenesis of these crystals and their role in pediatric arthritis and joint infection.

- Citation: Pavlis W, Constantinescu DS, Murgai R, Barnhill S, Black B. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals in a 9-year-old with osteomyelitis of the knee: A case report. World J Orthop 2022; 13(9): 870-875

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v13/i9/870.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v13.i9.870

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD), formerly known as pseudogout, is a common inflammatory arthritis that may asymptomatically present as chondrocalcinosis or as episodes of acute calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystal arthritis. Increasing age is one of the strongest risk factors for the condition, with the condition rarely seen before the age of 40 and common in patients over 80[1]. In cases where the condition has been identified in patients under 40, risk factors such as genetic predisposition or metabolic disorders are almost always present[2]. In this report, we present the case of a 9-year-old male with no past medical history developing CPP crystals in the synovial fluid of the knee during an episode of osteomyelitis caused by cat scratch injury. The patient’s mother consented to the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

A 9-year-old, African American male presented to the emergency room accompanied by his mother with right knee pain of 5 d duration.

The patient stated that the pain began after he was scratched by a cat 5 d prior to presentation. His mother noticed her son was not bearing weight on the right lower extremity 2 d after the incident. He described the pain as constant and worsening and aggravated by both passive movement of the knee and weight bearing of the extremity. The patient and his mother denied any history of fever or drainage from the wound but did report antecedent upper respiratory infection symptoms one week prior. He had not trialed NSAIDs or acetaminophen for the injury. The patient was in the 2nd grade and lived with both parents. The orthopedics service was consulted to rule septic arthritis of the right knee.

The patient had no past medical history.

The patient had no relevant family history, including no history of metabolic disorders such as hereditary hemochromatosis or hyperparathyroidism.

Focused examination of the right lower extremity demonstrated warmth and swelling across the knee. Superficial scratches were noted across the anterolateral leg. One punctate wound on the lateral knee was noted without erythema or drainage. Thigh and leg compartments were soft and compressible. Significant pain was reproduced with both axial loading and passive range of motion of the knee from 0°-40°. Sensation and motor function were intact in all nerve distributions with palpable distal pulses and brisk capillary refill in all toes.

Initial laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 8.9, C-reactive protein of 1.1, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 39. The patient had a calcium level of 9.7 and alkaline phosphatase of 209. Due to the clinical concern for septic arthritis, joint aspiration was performed. Aspiration yielded 10 mL of cloudy, viscous, yellow fluid. Follow-up cell counts of the synovial fluid yielded a glucose of 99, protein of 4.9, and a WBC of 7,345 with 59% polymorphic neutrophils. Positively birefringent, rhomboid shaped crystals were present and identified as calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the fluid were both negative for any growth. This synovial fluid analysis was suggestive of an inflammatory origin and a preliminary diagnosis of CPP arthritis was made.

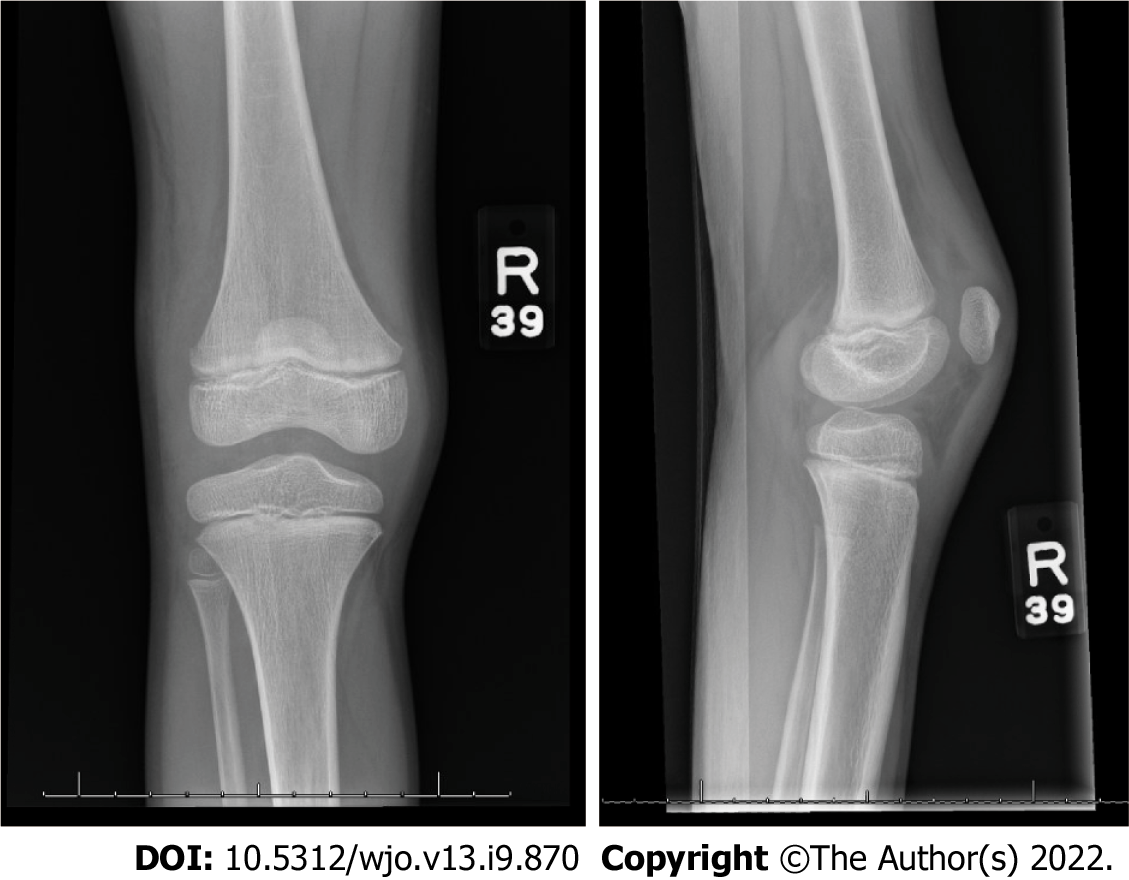

Radiographs of the right knee demonstrated a joint effusion within the suprapatellar recess and trace effusion within Hoffa’s fat pad (Figure 1). No chondrocalcinosis was observed. Follow-up ultrasound of the right knee was performed for comparison, which showed a simple fluid collection in the knee joint.

The patient was placed in an ace wrap for compressive dressing, started on oral ibuprofen, intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone and clindamycin, and admitted for additional work-up. Pediatric infectious disease was consulted and elected to continue ongoing antibiotic management and perform Bartonella titers, which were negative. On the third day of admission, MRI with IV contrast was performed and significant for a focal, intra-synovial area of enhancing, 6 mm cortical defect at the lateral border of the lateral femoral condyle (Figure 2). Additionally, a small joint effusion and subcutaneous soft tissue edema overlying the proximal tibia, rim enhancement suggestive of synovitis, and a collection within the inflammatory changes of the vastus lateralis with rim enhancement suggesting small abscess formation were also found.

A diagnosis of osteomyelitis was made with a rare, incidental finding of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals in synovial fluid analysis of the knee.

Antibiotic management was changed to IV ampicillin-sulbactam due to concern for Pasteurella secondary to cat scratch. A diagnosis of CPPD was considered very unlikely due to the patient’s young age, lack of previous episodes or family history of CPPD, and absence of other medical issues considered risk factors for CPPD, such as hyperparathyroidism, hereditary hemochromatosis, chronic kidney disease, or loop diuretic use.

Debridement of the osteomyelitis and needle aspiration of the soft-tissue abscess were not performed due to the small size of the deformities and marked clinical improvement in the patient. Due to this, no cultures or drug sensitives of the abscess or bone were performed. By the fourth day of admission, the patient had remained afebrile, his CRP had decreased to less than 0.5, his right knee had become significantly less edematous, and he no longer endorsed pain or reduced range of motion. After final discussion with the infectious disease team, the decision was made to discharge the patient with a 4-wk supply of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. The patient did not require physical therapy and was discharged without a walker. The patient was referred for follow-up in the infectious disease to ensure resolution of symptoms and monitor for side effects of antibiotic treatment. The mother was agreeable with the nonoperative management of her son and counseled to return to the emergency room if symptoms recurred.

At 6-wk follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, had completed his course of oral antibiotics, and had returned to prior function. The patient’s mother reported no ongoing noticeable disability or changes in her child. She reported overall satisfaction with the treatment of her child and the quality of care she received from the physician, nursing, and physical therapy staff during her son’s hospitalization.

In this case, we present the rare finding of CPP crystals in the synovial fluid of a healthy 9-year old child with osteomyelitis and a soft-tissue abscess following minor knee trauma. CPPD is a common inflammatory arthritis with a strong association with increasing age. A community prevalence study in the United Kingdom found the mean age of individuals with the condition to be 63.7, with prevalence increasing from 3.7% in those aged 55-59 to 17.5% in those aged 80-84[3]. Cases are very rarely identified in patients under the age of 40. In a study of a region encompassing one million people in Sweden, only 6 of 706 cases were identified in individuals under the age of 34, with the youngest patient being 20[4].

In the literature, few reports of CPPD in younger patients have been published, with most being associated with significant relevant co-morbidities[5-9]. The youngest cases of CPPD disease identified from the literature were two 16 year old patients in Germany[9]. The condition’s occurrence in those younger than 55 has been linked to familial hereditary predisposition and metabolic conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, hypophosphatasia, and hypomagnesemia[2]. In two prior cases, patients presented with CPPD disease at age 24 and 31 despite no relevant co-morbidities or similar familial occurrence[6,7]. The patient in this case similarly demonstrated no metabolic or genetic abnormalities and lacked any similar family history. Acute attacks of CPPD are often found in the setting of acute joint trauma or illness, making this patients concomitant trauma and osteomyelitis a likely inciting factor[2]. However, the pathogenesis of this condition is still not fully understood, and this case highlights the need for more research on the role of join trauma and inflammation on the development of CPPD.

CPPD is frequently asymptomatic and believed to be severely underdiagnosed. One study found that CPP crystals were present in the synovial fluid of 30% of patients undergoing knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis[10]. Diagnosis rates are dependent on methods of diagnosis. The identification of articular chondrocalcinosis on radiographs is a common means of diagnosis; however, studies of prevalence of the condition using this method vary widely based on the type and number of joints examined[1]. The most accurate form of diagnosis remains the identification of positively birefringent, rhomboid-shaped crystals in synovial fluid from the affected joint. In this study, no chondrocalcinosis was observed despite the identification of CPP crystals in synovial fluid.

This study is limited by the short follow-up period. Further follow-up will be required to evaluate the significance of this finding in the setting of this young patient’s acute injury. Additionally, this patient was not formally screened for several metabolic conditions associated with early-onset CPPD, such as hereditary hemochromatosis and hyperparathyroidism. Observation for repeat episodes of acute joint pain or the development of chondrocalcinosis will require further investigation for underlying causes of CPPD. However, this case report successfully presents findings of CPP crystals in a pediatric patient younger than any other previous reported in the literature. Further research could generate key findings on the pathogenesis of these crystals in the setting of trauma and infection in pediatric patients.

CPPD is a common form of arthritis with still relatively little known about its pathogenesis and prevalence. The condition is rarely identified in those under the age of 40. In this study, we present the rare case of a 9-year-old with CPP crystals in the synovial fluid of the knee during an episode of osteomyelitis. This rare finding presents further questions regarding the pathogenesis of the condition and its role in pediatric joint infection and arthritis. Future diagnostic studies among pediatric populations may identify additional cases of CPP crystals in children and shed new insights on the mechanisms of CPP deposition.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lim SC, South Korea; Yang F, China S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Abhishek A. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease: a review of epidemiologic findings. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rosenthal AK, Ryan LM. Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2575-2584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Neame RL, Carr AJ, Muir K, Doherty M. UK community prevalence of knee chondrocalcinosis: evidence that correlation with osteoarthritis is through a shared association with osteophyte. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hameed M, Turkiewicz A, Englund M, Jacobsson L, Kapetanovic MC. Prevalence and incidence of non-gout crystal arthropathy in southern Sweden. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bradley JD. Pseudoseptic pseudogout in progressive pseudorheumatoid arthritis of childhood. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987;46:709-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hammoudeh M, Siam AR. Pseudogout in a young patient. Clin Rheumatol. 1998;17:242-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hayashi M, Matsunaga T, Tanikawa H. Idiopathic widespread calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease in a young patient. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31:246-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Unlu Z, Tarhan S, Ozmen EM. An idiopathic case of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease with crowned dens syndrome in a young patient. South Med J. 2009;102:949-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fuchsberger T, Pillukat T, van Schoonhoven J, Prommersberger KJ. [Acute and chronic calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease in young patients]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2012;44:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Derfus BA, Kurian JB, Butler JJ, Daft LJ, Carrera GF, Ryan LM, Rosenthal AK. The high prevalence of pathologic calcium crystals in pre-operative knees. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:570-574. [PubMed] |