Published online Sep 18, 2021. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i9.700

Peer-review started: February 25, 2021

First decision: March 31, 2021

Revised: April 8, 2021

Accepted: August 24, 2021

Article in press: August 24, 2021

Published online: September 18, 2021

Processing time: 201 Days and 6.1 Hours

Non-emergent low-back pain (LBP) is one of the most prevalent presenting complaints to the emergency department (ED) and has been shown to contribute to overcrowding in the ED as well as diverting attention away from more serious complaints. There has been an increasing focus in current literature regarding ED admission and opioid prescriptions for general complaints of pain, however, there is limited data concerning the trends over the last decade in ED admissions for non-emergent LBP as well as any subsequent opioid prescriptions by the ED for this complaint.

To determine trends in non-emergent ED visits for back pain; annual trends in opioid administration for patients presenting to the ED for back pain; and factors associated with receiving an opioid-based medication for non-emergent LBP in the ED

Patients presenting to the ED for non-emergent LBP from 2010 to 2017 were retrospectively identified from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey database. The “year” variable was transformed to two-year intervals, and a weighted survey analysis was conducted utilizing the weighted variables to generate incidence estimates. Bivariate statistics were used to assess differences in count data, and logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with patients being discharged from the ED with narcotics. Statistical significance was set to a P value of 0.05.

Out of a total of 41658475 total ED visits, 3.8% (7726) met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. There was a decrease in the rates of non-emergent back pain to the ED from 4.05% of all cases during 2010 and 2011 to 3.56% during 2016 and 2017. The most common opioids prescribed over the period included hydrocodone-based medications (49.1%) and tramadol-based medications (16.9), with the combination of all other opioid types contributing to 35.7% of total opioids prescribed. Factors significantly associated with being prescribed narcotics included age over 43.84-years-old, higher income, private insurance, the obtainment of radiographic imaging in the ED, and region of the United States (all, P < 0.05). Emergency departments located in the Midwest [odds ratio (OR): 2.42, P < 0.001], South (OR: 2.35, < 0.001), and West (OR: 2.57, P < 0.001) were more likely to prescribe opioid-based medications for non-emergent LBP compared to EDs in the Northeast.

From 2010 to 2017, there was a significant decrease in the number of non-emergent LBP ED visits, as well as a decrease in opioids prescribed at these visits. These findings may be attributed to the increased focus and regulatory guidelines on opioid prescription practices at both the federal and state levels. Since non-emergent LBP is still a highly common ED presentation, conclusions drawn from opioid prescription practices within this cohort is necessary for limiting unnecessary ED opioid prescriptions.

Core Tip: A trend of diminishing opioid prescription for low back pain in the emergency department can be appreciated over a span of eight years. Such a trend may be a reflection of policies and guidelines aiming at opioid regulation. Factors that may increase the likelihood of opioid prescription for low back pain include age over 43.84-years-old, higher income, private insurance, the obtainment of radiographic imaging in the emergency department, and presenting within the Midwest/South/West regions of the United States. Providers should be cognizant of such risk factors given the burden imposed by opioid prescriptions on the healthcare system.

- Citation: Gwam CU, Emara AK, Chughtai N, Javed S, Luo TD, Wang KY, Chughtai M, O'Gara T, Plate JF. Trends and risk factors for opioid administration for non-emergent lower back pain . World J Orthop 2021; 12(9): 700-709

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v12/i9/700.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i9.700

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common healthcare complaints and musculoskeletal disorders seen in the emergency department (ED)[1,2]. The prevalence of LBP ranges from 49% to greater than 80% in the United States[3]. While non-emergent LBP can be treated by primary care physicians, studies suggest that patients will visit the ED for evaluation of symptoms, potentially leading to overcrowding and distracting from other serious health complaints[4,5]. Patients presenting to the ED for non-emergent LBP have been found to receive unnecessary imaging with excess radiation, be admitted to the hospital for pain control, or be given prescriptions of opioid pain medication[6-8].

Studies have shown inconclusive results in the efficacy using opioids to treating patients for LBP, with worse outcomes at 6-month follow-up. Furthermore, studies have shown similar efficacy of opioids compared to non-opioid medications in the treatment of both acute and chronic LBP[9-12]. Within the past decade, opioid prescribing for non-cancer pain has increased dramatically, along with an increase in opioid abuse and resulting deaths[13-16]. Davies et al[16] analyzed opioid prescribing rates from January 2005 to December 2015, stratifying patients by age. Their findings revealed that opioid prescriptions in patients older than the age of 85 increased nearly 2-fold. The American College of Emergency Physicians recommends utilizing opioids in the ED only when pain is severe, debilitating, or refractory to other treatments[17]. Further guidelines were mandated by the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, recommending opioids as a second-line treatment[18]. Despite the calls for regulation, evidence of deviation from guideline recommendations persists. Indeed, Hayden et al[19] reported 5% of previously opioid-naïve patients who present to the emergency department for low back pain become prolonged opioid users.

Temporal trends of ED visits for LBP, opioid prescription patterns for non-emergent LBP, and patient factors associated with receiving an opioid prescription have not been well documented but are necessary to combat the continuing opioid epidemic in the United States. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine trends in non-emergent ED visits for back pain; annual trends in opioid prescriptions for patients presenting to the ED for back pain; and factors associated with receiving an opioid based prescription for non-emergent LBP in the ED

This was a retrospective study. The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) was reviewed between the years 2010 and 2017. The NHAMCS is publicly available and is designed to collect data on the utilization and provision of ambulatory care services in hospital, emergency, and ambulatory care departments. Data is obtained from a sample of visits to non-federally employed office physicians. Prior to 2012, NHAMCS relied on paper instruments; the survey switched to computerized data collection in 2012. Each physician is randomly assigned to a one-week reporting period. During this period, data for a systematic random sample of visits are recorded by United States Census interviewers using a computerized Patient Record form. The survey uses a four-stage probability design with samples of primary sampling units (PSUs), hospitals within PSUs, clinics and emergency service areas within hospitals, and patient visits within clinics and emergency service areas. More details on NHAMCS can be found at cdc.gov.

Patients were included if they presented to one of the aforementioned ambulatory care settings captured by the NHAMCS with a complain of back pain. Patients with back pain were identified using the following string codes as a chief complaint: (1) “Back symptoms”; (2) “Back pain, ache, soreness, discomfort“; (3) “Back cramps, contractures, spasms”; (4) “Low back pain, ache, soreness, discomfort”; and (5) “Low back cramps, contractures, spasms”. Patients were excluded if they were under the age of 18 or were admitted for inpatient hospital stay.

A weighted survey analysis was conducted utilizing the weighted variables to generate incidence estimates. A chi-square analysis was performed to assess differences in count data. The “year” variable was transformed to two-year intervals as per the recommendations by the Center for Disease Prevention and Control[20]. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with patients being discharged from the ED with narcotics. Group variables entered into our logistic regression model were removed if all group level’s P-value exceeded 0.1. Presenting pain was discretized to the following categories: “Low” = 0 to 3; “moderate” = 4 to 6; and “severe” = 7 or more. A P value of 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance. All statistical analysis was conducted using R statistical software (Vienna, Austria). The ‘survey’ package was utilized to analyze survey data.

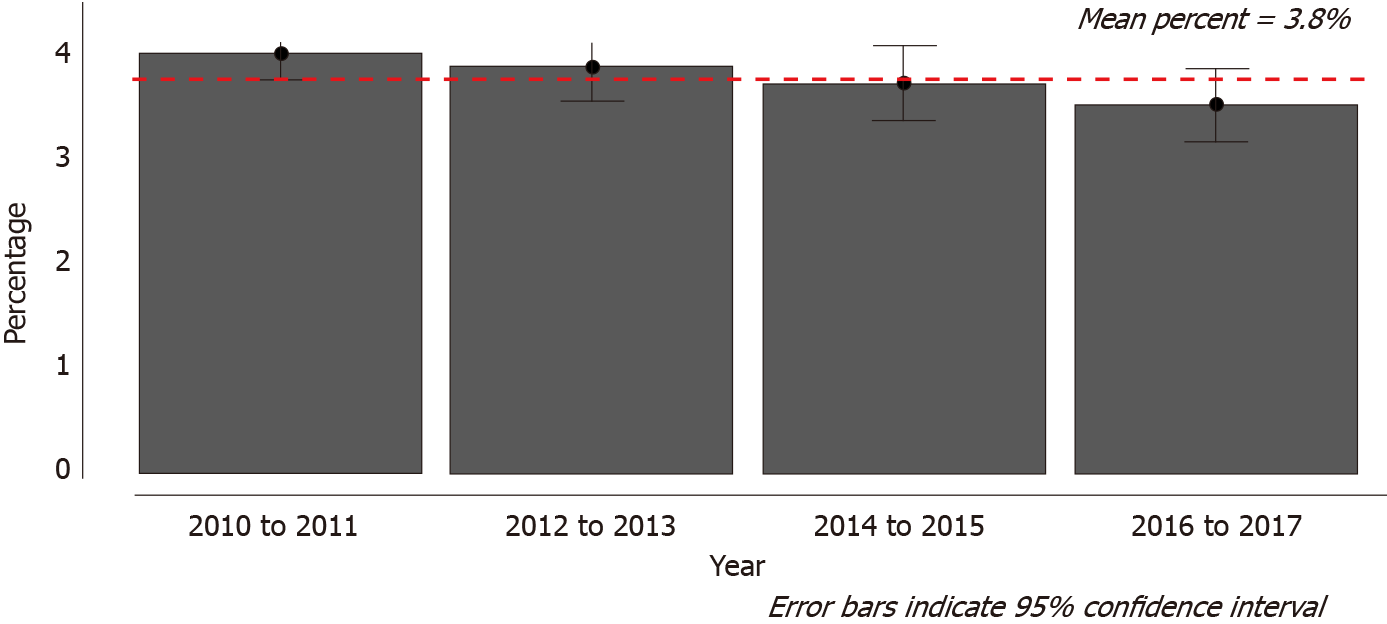

After implementation of inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study group included 7726 cases, which was 3.8% of the 41658475 total ED visits [95% confidence interval (CI): 34317928 to 48999021] (95%CI: 3.65% to 3.99%). There was a decrease in the rates of non-emergent back pain to the ED from 4.05% of all cases (95%CI: 3.81 to 4.31) during 2010 and 2011 to 3.56% (95%CI: 3.21 to 3.91) during 2016 and 2017 (Figure 1).

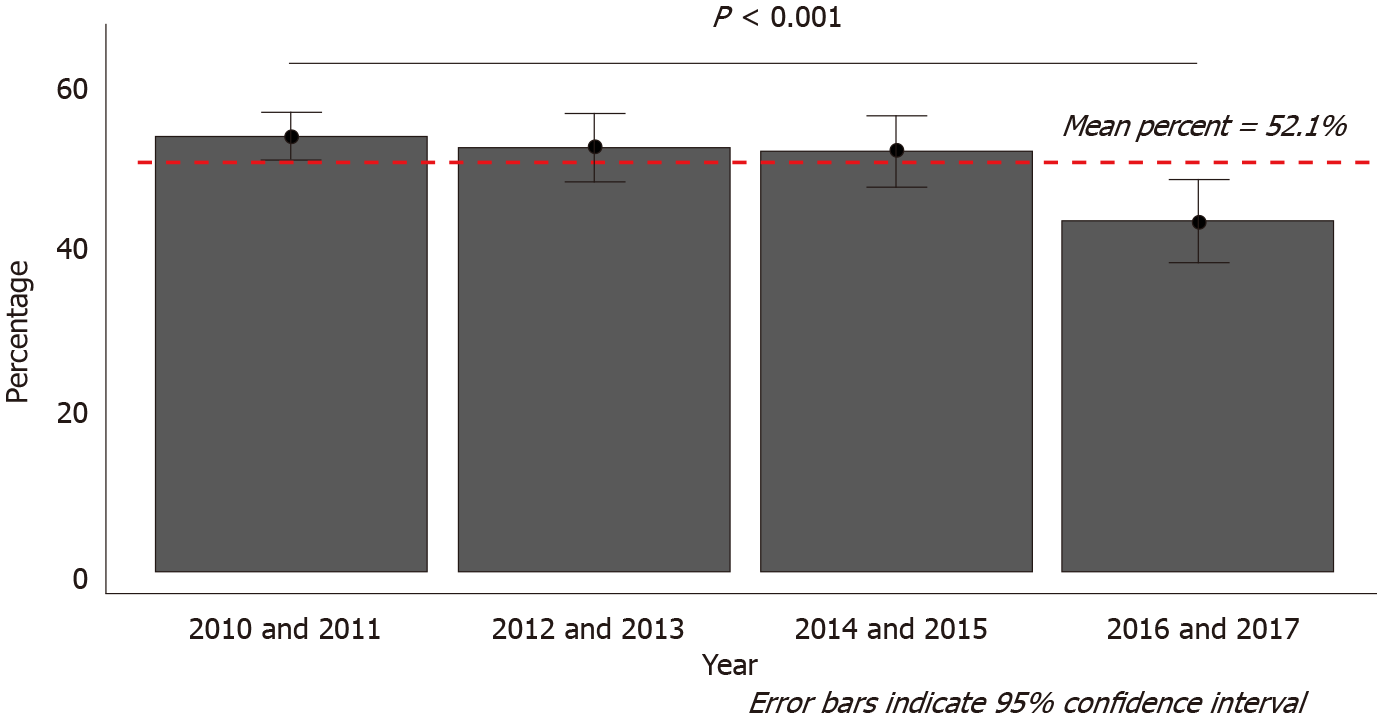

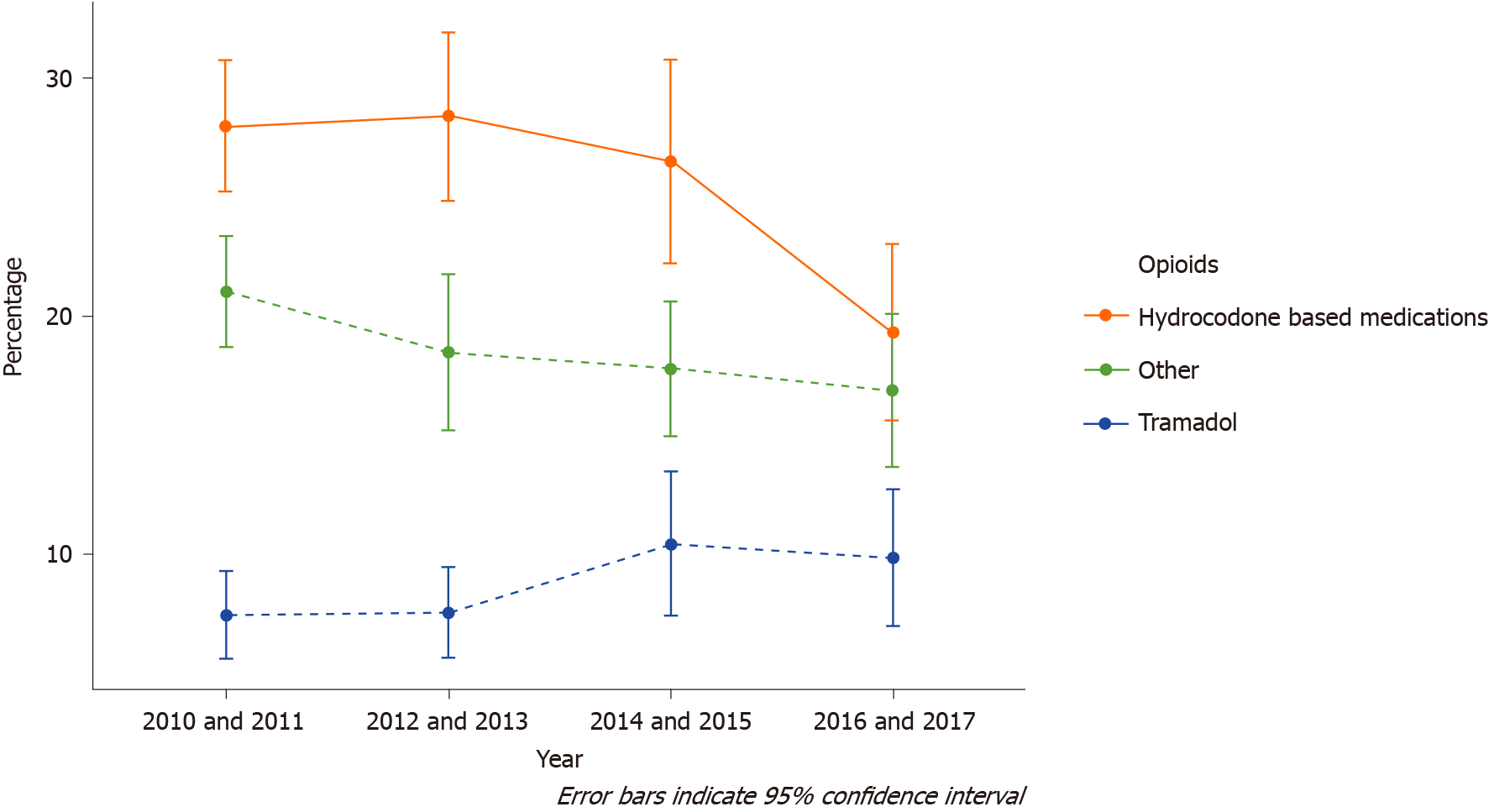

Fifty-two percent of all cases that presented to the ED for non-emergent LBP were prescribed an opioid-based medication between 2010 and 2017 (95%CI: 49.9% to 54.0%). However, the rates of opioid-based prescriptions decreased between the period of 2010 and 2011 (55.9%; 95%CI: 52.9% to 58.9%) and the period of 2016 and 2017 (45.0%; 95%CI: 39.86% to 50.22%) (Figure 2). The most common opioids prescribed included hydrocodone-based medications (49.1% of all opioids prescribed; 95%CI: 46.3% to 52.0%) and tramadol-based medications (16.9% of all opioids prescribed; 95%CI: 14.8% to 19.0%), with the combination of all other opioid types contributing to 35.7% (95%CI: 32.6% to 39.0%) of total opioids prescribed.

Trend analysis revealed a decrease in the prescriptions of hydrocodone-based medications for non-emergent LBP patients presenting to the ED between the period of 2010 and 2011 (28.0%; 95%CI: 25.3% to 30.7%) to the period of 2016 and 2017 (19.3%; 95%CI: 15.6% to 23.1%). However, there was no notable change in the rates of non-emergent LBP patients that received tramadol or other opioid types (Figure 3).

Estimated household income was associated with receiving an opioid base narcotic. When compared to patients coming from the lowest income quartile (below 32793 dollars annually), patients belonging to the third income quartile (40627 dollars to 52387 dollars annually) had higher odds of receiving an opioid based medication [odds ratio (OR): 1.35; 95%CI: 1.13 to 1.61; P ≤ 0.001] (Table 1). Patients who were privately insured (OR: 1.29; 95%CI: 1.04 to 1.58; P = 0.018) or were self-payers (OR: 1.25; 95%CI: 1.00 to 1.56; P = 0.048) had higher odds of receiving an opioid based medication when compared to Medicaid patients. Other factors associated with being discharged with opioid based medications included if radiographic images were obtained (OR: 1.47; 95%CI: 1.30 to 1.66; P < 0.001), age greater than 43.94-years (OR: 1.01; 95%CI: 1.00 to 1.01; P = 0.001), and if patients reported having severe back pain (OR: 2.14; 95%CI: 1.63 to 2.81; P < 0.001). ED location was also significantly associated with opioid prescription for back pain. Emergency departments located in the Midwest (OR: 2.42; 95%CI: 1.94 to 3.01; P < 0.001), South (OR: 2.35; 95%CI: 1.91 to 2.88; P < 0.001), and West (OR: 2.57; 95%CI: 1.94 to 3.42; P < 0.001) all yielded greater odds of prescribing opioid-based medications for non-emergent LBP when compared to EDs in the Northeast region.

| Odds ratio | Lower 95%CI | Upper 95%CI | P value | |

| Home income [quartile 1 (below 32793 dollars)] | Reference | |||

| Home income [quartile 2 (32794-40626 dollars)] | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1.40 | 0.078 |

| Home income [quartile 3 (40627-52387 dollars)] | 1.35 | 1.13 | 1.61 | 0.001 |

| Home income [quartile 4 (52388 dollars or more)] | 1.11 | 0.91 | 1.34 | 0.318 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicaid | Reference | |||

| Medicare | 1.03 | 0.84 | 1.28 | 0.753 |

| Other | 1.38 | 0.71 | 2.67 | 0.337 |

| Private insurance | 1.29 | 1.04 | 1.58 | 0.018 |

| Self-pay | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.56 | 0.048 |

| Workers compensation | 1.10 | 0.72 | 1.70 | 0.660 |

| Images obtained | 1.47 | 1.30 | 1.66 | < 0.001 |

| Mean centered age | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.001 |

| Pain-low | Reference | |||

| Pain-moderate | 1.28 | 0.96 | 1.71 | 0.093 |

| Pain-severe | 2.14 | 1.63 | 2.81 | < 0.001 |

| Seen in ED within the last 72 hr | 0.77 | 0.56 | 1.06 | 0.106 |

| United States Census Region | ||||

| Northeast | Reference | |||

| Midwest | 2.42 | 1.94 | 3.01 | < 0.001 |

| South | 2.35 | 1.91 | 2.88 | < 0.001 |

| West | 2.57 | 1.94 | 3.42 | < 0.001 |

While it has been shown that the overall prescription rates of opioids within the United States are gradually decreasing over the past five years, there is a paucity of literature evaluating trends in opioid prescriptions specifically in patients presenting to the ED with non-emergent LBP[21]. Overall, our study reports a significant decrease in the number of non-emergent LBP ED visits from 2010 to 2017, as well as a decrease in opioids prescribed at these visits. Furthermore, we noted several independent risk factors for increased opioid prescription following non-emergent LBP, including age over 43.84-years-old, higher income, private insurance, the obtainment of radiographic imaging in the ED, and region of the United States.

Our findings are consistent with previous literature demonstrating an overall decrease in ED opioid prescriptions[22-25]. Marra et al[22] analyzed NHAMCS information from 2005 to 2015 for patients presenting to the ED with pain of all causes, finding that prescribing rates at discharge decreased significantly by 32% during the study duration[22]. Since pain is one of the most common reasons for ED visits, a major limitation of Marra et al[22] study was grouping pain causes into a single cohort. The decrease in opioid prescriptions for non-emergent LBP found in our study was representative of the overall decrease in ED opioid prescriptions for general pain over a similar time interval as established by Marra et al[22]. As such, our findings provide needed granularity in terms of specifically the non-emergent LBP population presenting to the ED

In elderly individuals, non-emergent LBP has been shown to have a prevalence ranging from 21.7% to 75%, with a direct correlation between age and LBP[26]. Our findings suggest that older age is an independent risk factor for increasing opioid prescriptions following ED admission for LBP, which may perhaps be due to older individuals presenting with increased severity of back pain. Severity of non-emergent LBP is known to be highly correlated with increasing age, particularly relative to other common causes of opioid prescriptions following ED admission such as pain secondary to trauma[27,28]. This increased LBP severity in older patients likely contributed to the increased opioid prescriptions in older patients shown in our analysis.

In particular, our study found age over 43.84-years to be an independent risk factor for opioid pres

With respect to insurance status, Ali et al[29] reported that 8% of patients with private insurance had potentially problematic opioid prescriptions, compared to 14% of patients with Medicaid. Problematic opioid prescription was defined in their study as opioid prescriptions which did not match the indication severity based on protocol established in previous literature[29]. Although our study did not address problematic opioid prescriptions, we did find that patients with private insurance or who were self-payers were more likely to be prescribed an opioid for non-emergent LBP compared to Medicaid patients.

In terms, of the Medicaid population specifically, Janakiram et al[25] performed a multistate analysis utilizing the Truven Marketscan Database from 2013 to 2015 and found Medicaid patients were more likely to receive prescriptions from an ED provider compared to a general practitioner, with back pain (14%) being the third leading cause for receiving an opioid prescription. Implementation of prior authorization plans within Medicaid plans has shown to not only minimize opioid-related morbidity within this cohort, but also discourage the initiation of long-acting opioid therapy[30,31]. Interestingly, studies have shown patients who present to the ED could be more appropriately managed by their primary care physician, which would potentially driving down ED visits. These studies demonstrate that adequate care reduces annual ED visits and decreases healthcare expenditure[32-34], therefore, lack of access to primary care may be the driving force of increasing patient visits to the ED especially for non-emergent indications such as LBP[35-37]. In other words, limited access to various primary care is likely associated with increased ED visits in patients with underlying mental and physical comorbid conditions.

Extended access primary care services have also been shown to decreased the amount of ED visits as well as pain prescriptions for non-emergent presentations[33]. Extended access primary care services offer patients the ability to book appointments outside of core contractual hours, either in the early morning, evening or at weekends. Whittaker et al[33] measured the impact of extended access in 56 primary care practices by offering seven-day extended access through providing care during the evenings and weekends, compared to 469 primary care practices with routine working hours. Implementing this extended access of care demonstrated a reduction in both the frequency and cost of patient-initiated ED visits for “minor” problems[33]. The majority of non-emergent LBP fits within this categorization of “minor” problems, so it is possible that more widespread extended access primary care services have the potential to reduce ED admissions and opioid prescriptions.

LBP has also been shown to be more prevalent and severe in older men compared to older women. Interestingly, our study found no difference in opioid prescriptions between men and women presenting to the ED with non-emergent LBP[38].

Finally, numeric pain scores have been implicated in contributing to the prescribed opioid epidemic, with opioids being administered to those who report higher pain scores[39]. In a recent cross-sectional study, Monitto et al[40] explored the association of patient factors with opioid dispensing, consumption, and medication remaining on completion of therapy after hospital discharge. Their findings suggest higher discharge pain scores can predict higher opioid dispensing and consumption. This is consistent with our findings as increasing pain scales was significantly associated with discharge from the ED with an opioid prescription. With further validation, these pain scales can be potentially utilized to predict and ultimately standardize the number of opioids patients presenting to the ED with non-emergent LBP should be prescribed.

This study has a few limitations which must be considered when interpreting our results, most of which are inherent to the use of an administrative database. First, recent studies have addressed concern regarding the validity of the NHAMCS database due to slight variability in documentation across the years[41]. Our study limited this potential issue by purposely utilizing variables that were collected in a consistent fashion over the years studied. Second, since information from the database is ascertained from individual ED visits, the study did not allow for longitudinal information on these patients or allowing us to determine the appropriateness of therapy[22]. For example, we were unable to identify patients with a history of substance abuse. However, this limitation does not preclude the validity of our findings as our study methodology included only cases of non-emergent back pain that presented to the ED and did not warrant admission. Finally, our study assessed data from 2010 to 2017, as this was the only time interval available from NHAMCS. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable information regarding annual trends in ED visits for back pain, prescribing patterns, and patient risk factors for being discharged with an opioid prescription.

Despite legislative efforts to improve access to care, ED continue to be burdened by non-emergent maladies such as LBP. Our study demonstrated a significant decrease in number of patients presenting to the ED with non-emergent LBP between 2010 and 2017, as well as a significant decrease in opioids prescribed in the ED for this indication of the same time period. Regression analysis identified age over 43.84-years-old, higher income, private insurance, the obtainment of radiographic imaging in the ED, and region of the United States as independent risk factors for being discharged with prescription narcotics after presenting to the ED for LBP. Emergency departments located in the Northeast region were the least likely to discharge patients with narcotics. Ultimately, physician-directed patient education is necessary to minimize ED burden by non-emergent LBP, and a heightened awareness of previous narcotic prescribing practices is needed to mitigate narcotic prescriptions for patients presenting to the ED with non-emergent LBP. Future prospective studies are necessary to determine the impact of state and federal legislative mandates on the influence of opioid prescriptions given at discharge.

Low back pain a major cause of emergency department (ED) visits and ranges in incidence between 49% and 80% in the United States. Patients presenting to the ED for non-emergent LBP often receive unnecessary prescriptions of opioid pain medication.

Several guidelines have been implemented to mitigate opioid prescription for low-back pain. However, the impact of such guidelines is yet to be ascertained.

This study aimed to outline the trends of annual opioid prescriptions for patients presenting to the ED with non-emergent back pain; and risk factors associated with being prescribed an opioid based prescription for non-emergent LBP in the ED.

We reviewed the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey for all patients who presented to the ED with low back pain. Patients over 18 years of age who were not subsequently admitted were included. The primary outcome was opioid-based medication prescription. Trends and factors of opioid-based medication prescription were evaluated to identify chronological and patient-specific risk factors.

We reviewed the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey for all patients who presented to the ED with low back pain. Patients over 18 years of age who were not subsequently admitted were included. The primary outcome was opioid-based medication prescription. Trends and factors of opioid-based medication prescription were evaluated to identify chronological and patient-specific risk factors.

Overall opioid prescription demonstrated a mild decrease over the past decade; however, a pattern of diminished hydrocodone-based medications is associated with a mild increase in tramadol-based medication prescription. This pattern may be due to recent legislative guidelines.

Further research is required to identify future trends that may be a more veritable reflection of more recent policies regulating opioid prescription for low back pain – particularly tramadol based medications.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Reddy RS S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Bell JA, Burnett A. Exercise for the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of low back pain in the workplace: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:8-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Borczuk P. An evidence-based approach to the evaluation and treatment of low back pain in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2013;15:1-23. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Scott NA, Moga C, Harstall C. Managing low back pain in the primary care setting: the know-do gap. Pain Res Manag. 2010;15:392-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Edwards J, Hayden J, Asbridge M, Gregoire B, Magee K. Prevalence of low back pain in emergency settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kocher KE, Meurer WJ, Fazel R, Scott PA, Krumholz HM, Nallamothu BK. National trends in use of computed tomography in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:452-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Machado GC, Rogan E, Maher CG. Managing non-serious low back pain in the emergency department: Time for a change? Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30:279-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schlemmer E, Mitchiner JC, Brown M, Wasilevich E. Imaging during low back pain ED visits: a claims-based descriptive analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:414-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kyi L, Kandane-Rathnayake R, Morand E, Roberts LJ. Outcomes of patients admitted to hospital medical units with back pain. Intern Med J. 2019;49:316-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids for low back pain. BMJ. 2015;350:g6380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ashworth J, Green DJ, Dunn KM, Jordan KP. Opioid use among low back pain patients in primary care: Is opioid prescription associated with disability at 6-month follow-up? Pain. 2013;154:1038-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wertli MM, Steurer J. [Pain medications for acute and chronic low back pain]. Internist (Berl). 2018;59:1214-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Smith JA, Fuino RL, Pesis-Katz I, Cai X, Powers B, Frazer M, Markman JD. Differences in opioid prescribing in low back pain patients with and without depression: a cross-sectional study of a national sample from the United States. Pain Rep. 2017;2:e606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Deyo RA, Smith DH, Johnson ES, Donovan M, Tillotson CJ, Yang X, Petrik AF, Dobscha SK. Opioids for back pain patients: primary care prescribing patterns and use of services. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:717-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Chu A, Seow H, Howell D, Earle CC, O'Brien MA, Dudgeon D, Atzema C, Husain A, Liu Y, DeAngelis C. Opioid Prescribing Among Cancer and Non-cancer Patients: Time Trend Analysis in the Elderly Using Administrative Data. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54: 484-492. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Häuser W, Schug S, Furlan AD. The opioid epidemic and national guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a perspective from different continents. Pain Rep. 2017;2:e599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Davies E, Phillips C, Rance J, Sewell B. Examining patterns in opioid prescribing for non-cancer-related pain in Wales: preliminary data from a retrospective cross-sectional study using large datasets. Br J Pain. 2019;13:145-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Methods and Analytic Guidelines. [cited 20 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/survey_methods.htm. |

| 18. | Rosenbaum S, Authors F, Cheng D, Nima Majlesi F, Heller M, Steve Rosenbaum F, Michael Winters F. Clinical Practice Statement Emergency Department Opioid Prescribing Guidelines for the Treatment of Non-Cancer Related Pain (11/12/2013). [cited 20 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.aaem.org/UserFiles/file/Emergency-Department-Opoid-Prescribing-Guidelines.pdf. |

| 19. | Hayden JA, Ellis J, Asbridge M, Ogilvie R, Merdad R, Grant DAG, Stewart SA, Campbell S. Prolonged opioid use among opioid-naive individuals after prescription for nonspecific low back pain in the emergency department. Pain. 2021;162:740-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | National Center for Health Statistics. Ambulatory Health Care Data Homepage. [cited 20 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm. |

| 21. | Bohnert ASB, Guy GP Jr, Losby JL. Opioid Prescribing in the United States Before and After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 2016 Opioid Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:367-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Marra EM, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins P, Pines JM. Opioid Administration and Prescribing in Older Adults in U.S. Emergency Departments (2005-2015). West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:678-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Van Winkle PJ, Ghobadi A, Chen Q, Menchine M, Sharp AL. Association of age and opioid use for adolescents and young adults in community emergency departments. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:1397-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ward MJ, Kc D, Jenkins CA, Liu D, Padaki A, Pines JM. Emergency department provider and facility variation in opioid prescriptions for discharged patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:851-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Janakiram C, Fontelo P, Huser V, Chalmers NI, Lopez Mitnik G, Brow AR, Iafolla TJ, Dye BA. Opioid Prescriptions for Acute and Chronic Pain Management Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:365-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | de Souza IMB, Sakaguchi TF, Yuan SLK, Matsutani LA, do Espírito-Santo AS, Pereira CAB, Marques AP. Prevalence of low back pain in the elderly population: a systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2019;74:e789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J, Pransky G, Sieper J, Smeets RJ, Underwood M; Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391:2356-2367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1769] [Cited by in RCA: 2587] [Article Influence: 369.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van Tulder M, Koes B, Bombardier C. Low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:761-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ali MM, Tehrani AB, Mutter R, Henke RM, O'Brien M, Pines JM, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Potentially Problematic Opioid Prescriptions Among Individuals With Private Insurance and Medicaid. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70:681-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Keast SL, Kim H, Deyo RA, Middleton L, McConnell KJ, Zhang K, Ahmed SM, Nesser N, Hartung DM. Effects of a prior authorization policy for extended-release/long-acting opioids on utilization and outcomes in a state Medicaid program. Addiction. 2018;9:1651-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cochran G, Gordon AJ, Gellad WF, Chang CH, Lo-Ciganic WH, Lobo C, Cole E, Frazier W, Zheng P, Kelley D, Donohue JM. Medicaid prior authorization and opioid medication abuse and overdose. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23:e164-e171. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Vecchio N, Davies D, Rohde N. The effect of inadequate access to healthcare services on emergency room visits. A comparison between physical and mental health conditions. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Whittaker W, Anselmi L, Kristensen SR, Lau YS, Bailey S, Bower P, Checkland K, Elvey R, Rothwell K, Stokes J, Hodgson D. Associations between Extending Access to Primary Care and Emergency Department Visits: A Difference-In-Differences Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Birmingham LE, Cochran T, Frey JA, Stiffler KA, Wilber ST. Emergency department use and barriers to wellness: a survey of emergency department frequent users. BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Weinick RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1630-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Garcia TC, Bernstein AB, Bush MA. Emergency department visitors and visits: who used the emergency room in 2007? NCHS Data Brief. 2010;1-8. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:126-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1037] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ozcan Kahraman B, Kahraman T, Kalemci O, Salik Sengul Y. Gender differences in postural control in people with nonspecific chronic low back pain. Gait Posture. 2018;64:147-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Levy N, Sturgess J, Mills P. "Pain as the fifth vital sign" and dependence on the "numerical pain scale" is being abandoned in the US: Why? Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:435-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Monitto CL, Hsu A, Gao S, Vozzo PT, Park PS, Roter D, Yenokyan G, White ED, Kattail D, Edgeworth AE, Vasquenza KJ, Atwater SE, Shay JE, George JA, Vickers BA, Kost-Byerly S, Lee BH, Yaster M. Opioid Prescribing for the Treatment of Acute Pain in Children on Hospital Discharge. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:2113-2122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Mafi JN, Edwards ST, Pedersen NP, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Landon BE. Trends in the ambulatory management of headache: analysis of NAMCS and NHAMCS data 1999-2010. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:548-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |