Published online Jun 18, 2021. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i6.445

Peer-review started: February 15, 2021

First decision: May 3, 2021

Revised: May 4, 2021

Accepted: May 27, 2021

Article in press: May 27, 2021

Published online: June 18, 2021

Processing time: 116 Days and 6.3 Hours

Oblique lumbar interbody fusion is a mini-open retroperitoneal approach that uses a wide corridor between the left psoas muscle and the aorta above L5. This approach avoids the limitations of lateral lumbar interbody fusion, is considered less invasive than anterior lumbar interbody fusion, and is similarly effective for indirect decompression and improving lordosis while maintaining a low comp

Cases of three patients who underwent multilevel oblique lumbar interbody fusion including L5-S1, using one of the three different techniques, are described. All patients presented with symptomatic degenerative lumbar pathology and failed conservative management prior to surgery. The anatomical considerations that affected the decisions to utilize each approach are discussed. The pros and cons of each approach are also discussed. A parasagittal facet line objectively assesses the relationship between the left common iliac vein and the L5-S1 disc and assists in choosing the approach to L5-S1.

Oblique retroperitoneal access to L5-S1 in the lateral decubitus position is possible through three different approaches. The choice of approach to L5-S1 may be individualized based on a patient’s vascular anatomy using preoperative imaging. While most surgeons will rely on their experience and comfort level in choosing the approach, this article elucidates the nuances of each technique.

Core Tip: Oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) provides safe retroperitoneal access to nearly all lumbar levels, including L5-S1, thus, allowing single-position surgery. L5-S1 OLIF access may be attempted through three alternative approaches — left intra-bifurcation, left pre-psoas and right pre-psoas approaches — the choice of which can be customized according to the patient’s vascular anatomy.

- Citation: Berry CA. Nuances of oblique lumbar interbody fusion at L5-S1: Three case reports. World J Orthop 2021; 12(6): 445-455

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v12/i6/445.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i6.445

Oblique pre-psoas retroperitoneal access to the lumbar spine through a mini-open technique has recently gained popularity. The oblique trajectory avoids the iliac crest and lower ribs, which are impediments to lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF)[1]. Staying outside the psoas reduces the risk of lumbar plexus injuries[2,3], and allows complete muscle relaxation as neuromonitoring is not considered essential for this approach[4,5]. Moreover, a wide anatomic corridor between the left psoas and aorta allows easy access to all lumbar spinal levels above L5[6], often without the need for any vascular retraction or ligation[7].

Isolated L5-S1 pathologies can be approached through the anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) technique in the supine position, taking advantage of the wide corridor between the bifurcated common iliac vessels. However, the ALIF approach requires ligation of the left iliolumbar vein (ILV) and transposition of the great vessels to reach the levels above L5[8]. In contrast, oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF), or anterior to psoas (ATP) approach, performed with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, can address multiple lumbar levels, including L5-S1, with a relatively favorable complication profile[4,9]. The lateral decubitus position takes advantage of gravity-assisted retraction of the peritoneal sac, theoretically reducing the risk of postoperative ileus[10]. OLIF/ATP involves a mini-open muscle-splitting approach through the abdominal oblique and transverse muscles[11], which may be less traumatic than a midline ALIF approach through the anterior rectus muscle-sheath complex[12].

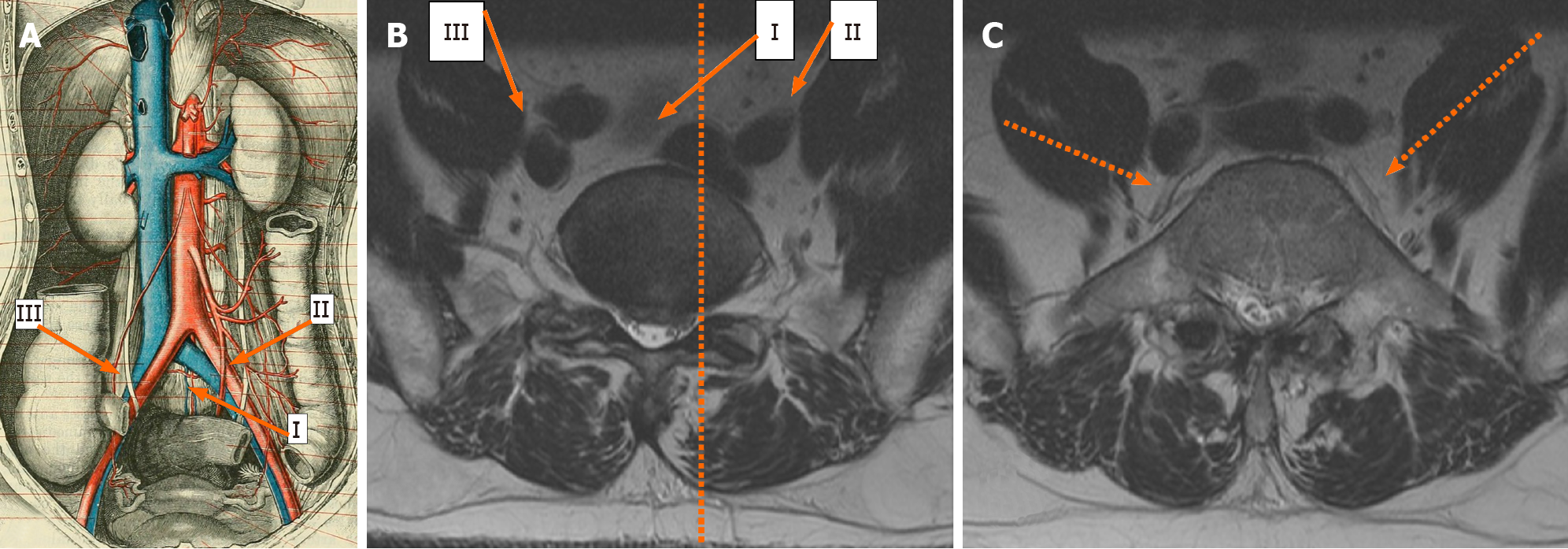

Oblique access to L5-S1 is not as straightforward as that for levels above L5. Variations in vascular anatomy create unique situations for which approaches may need to be customized. Oblique anterolateral approaches to L5-S1 have been described in previous studies as staying lateral to[4,13], or approaching between the bifurcated common iliac vessels[7] (Figure 1A and B). These variations of technique have been found to be safe and feasible in individual studies. However, these studies have not provided adequate guidance regarding the choice of approach. Careful assessment of the vascular anatomy is critical as vascular injuries range from 0.3%-4.3%, especially when L5-S1 is included[4,7,12]. Three representative case studies are presented to describe how the three previously described variations of approaches can be potentially customized based on a patient’s anatomy.

All patients in the case studies were operated on in a single institution by a single spine surgeon with assistance from an access surgeon. Imaging and chart review were retrospectively performed. All patients presented with degenerative lumbar pathology and underwent nonsurgical treatment for a minimum of 6-12 wk before being considered for surgical intervention. After careful consideration, each patient elected to proceed with surgery and provided written informed consent.

In the preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the location of the left common iliac vein (CIV) in relation to the L5-S1 disc was carefully assessed. We have previously described an imaginary parasagittal line drawn from the medial border of the left L5-S1 facet joint on the MRI axial section through the L5-S1 disc (the facet line)[13] and traced anteriorly to assess its relationship with the left CIV (Figure 1B). MRI axial images through the L5 vertebral body were also carefully evaluated to identify L5 segmental veins or ILV on either side[4] (Figure 1C). Computed tomography was not routinely performed to assess fusion.

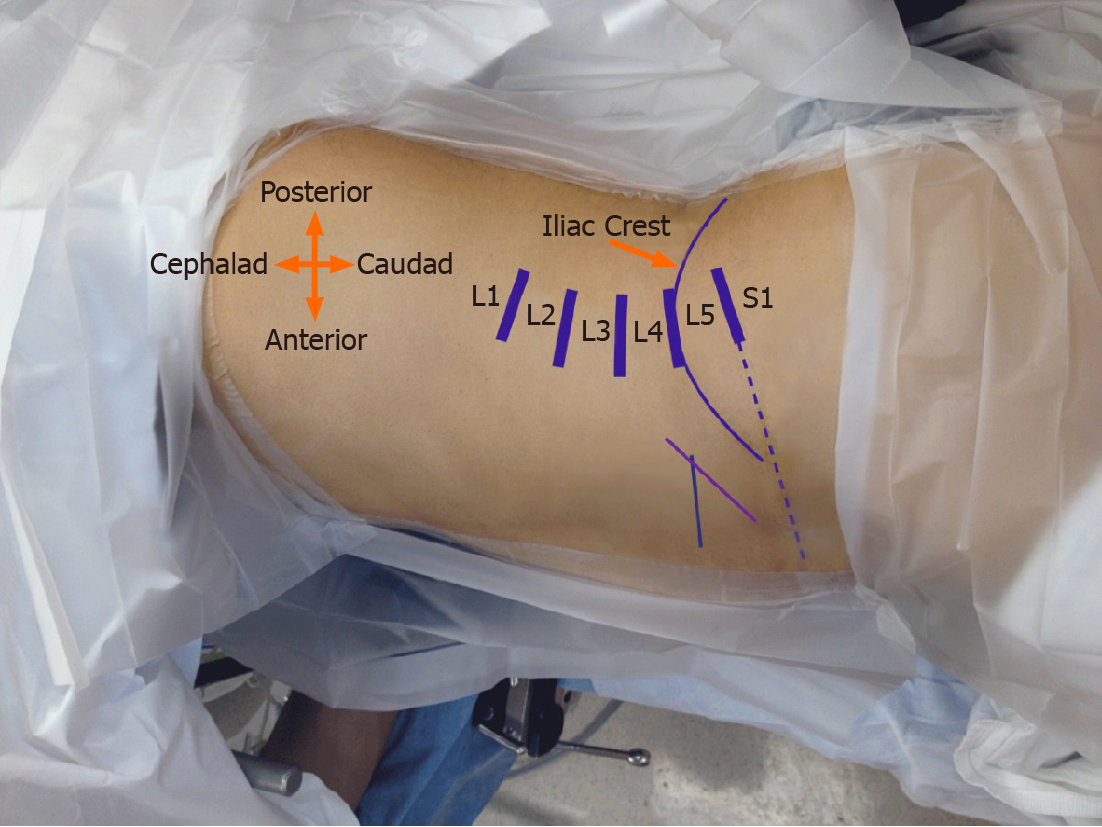

Left intra-bifurcation approach: The left intra-bifurcation approach has been described by Woods et al[7] and others[1,13-15] and is a modification of the supine ALIF technique. This is performed with the patient in the right lateral decubitus position. Lateral fluoroscopy is performed to mark all target spinal levels on the skin (Figure 2). An oblique 5-6 cm incision in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen is marked 2 fingerbreadths anterior to the anterior iliac crest and extending inferior enough to reach the plane of the sacral slope.

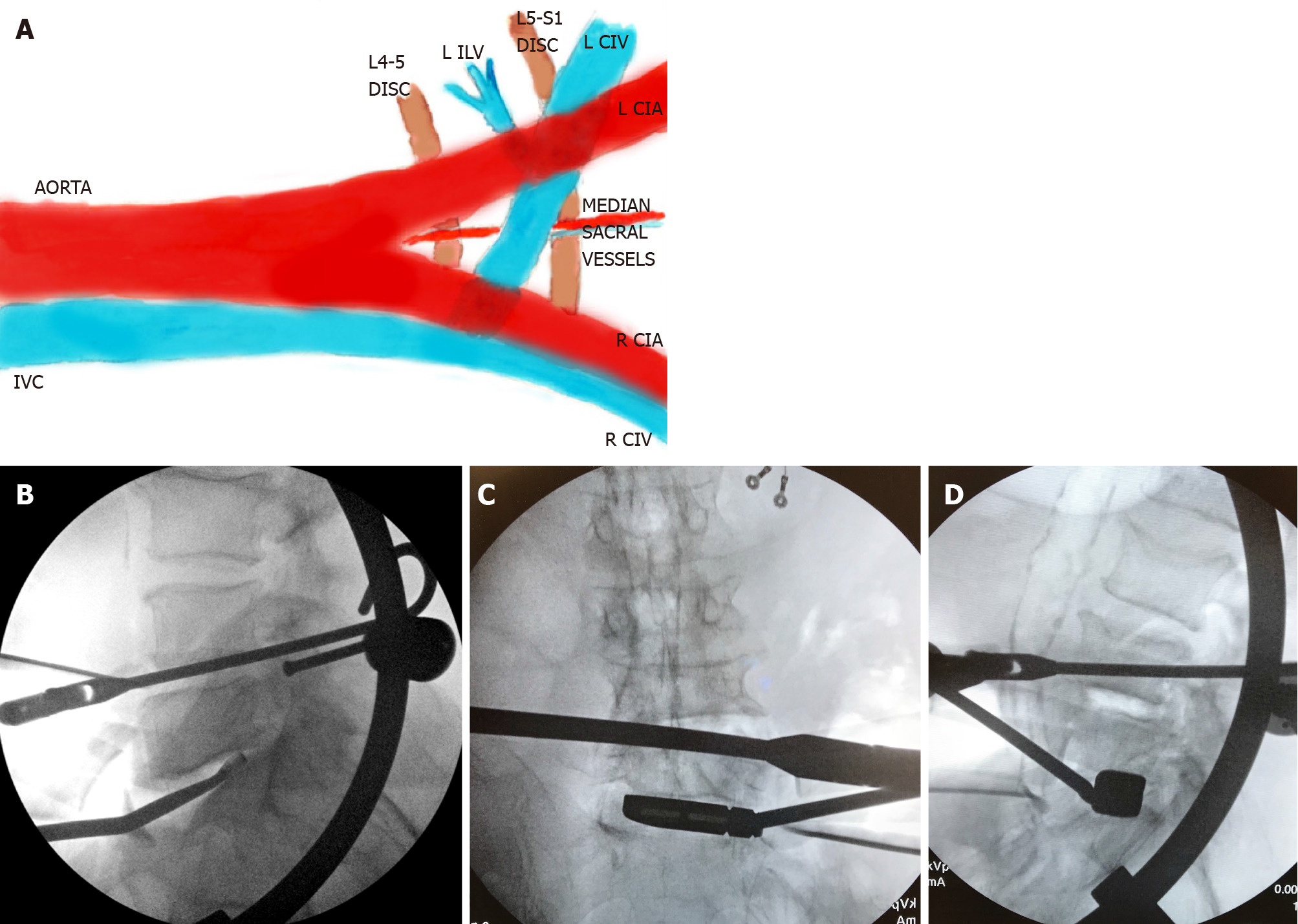

A muscle-splitting approach through the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles is performed, and the retroperitoneal space is entered. Blunt dissection is performed to reach the left psoas muscle. The peritoneal sac is then retracted further medially and inferiorly to reach the medial aspect of the left common iliac vessels. Careful blunt dissection is performed to identify the anterior annulus of the L5-S1 disc, which is confirmed with fluoroscopy. The median sacral vessels are identified and ligated (Figure 3A). Blunt dissection may be required to mildly elevate and retract the left CIV laterally to further widen the intra-bifurcation interval. Discectomy and endplate preparation is then performed at L5-S1. Double-bent curettes may be needed to adequately reach the posterior portion of the L5 inferior endplate (Figure 3B). An ALIF cage (width: 32-40 mm; height: 12-20 mm; depth: 24-32 mm; lordosis: 14-20o) packed with bone graft is inserted through an oblique inserter under image guidance. The anteroposterior (AP) fluoroscopy confirms the midline position of the cage. A screw with a washer or a plate is usually placed to cover the cage to prevent dislodgement.

Left pre-psoas approach: The left pre-psoas approach has been described by Tannoury et al[4] and others[13,16,17], and is an inferior continuation of the pre-psoas OLIF approach to levels above L5. As above, the patient is positioned in the right lateral decubitus position and spinal levels marked on the skin. A 4-5 cm incision is marked along the skin lines about 2 fingerbreadths anterior to the iliac crest, approximately mid-way between the target levels (Figure 2). A muscle-splitting approach through all abdominal wall layers is then performed to reach the retroperitoneal space. The left psoas muscle is identified and the pre-psoas interval is developed and extended inferiorly. The left CIV is identified. The left ILV is often identified inferior to the L4-5 disc, with psoas retraction (Figure 3A). Ligation of this left ILV may be required to allow anteromedial mobilization of the left CIV. This exposes the lateral annulus of the L5-S1 disc. Discectomy and endplate preparation is then performed using specialized instruments that are bent in two planes (Figure 3C and D). An LLIF cage (width: 45-55 mm; height: 10-16 mm; depth: 18-22 mm; lordosis: 6-18o) packed with bone graft is inserted through a lateral inserter under image guidance. Fluoroscopy confirms the coronal position of the cage.

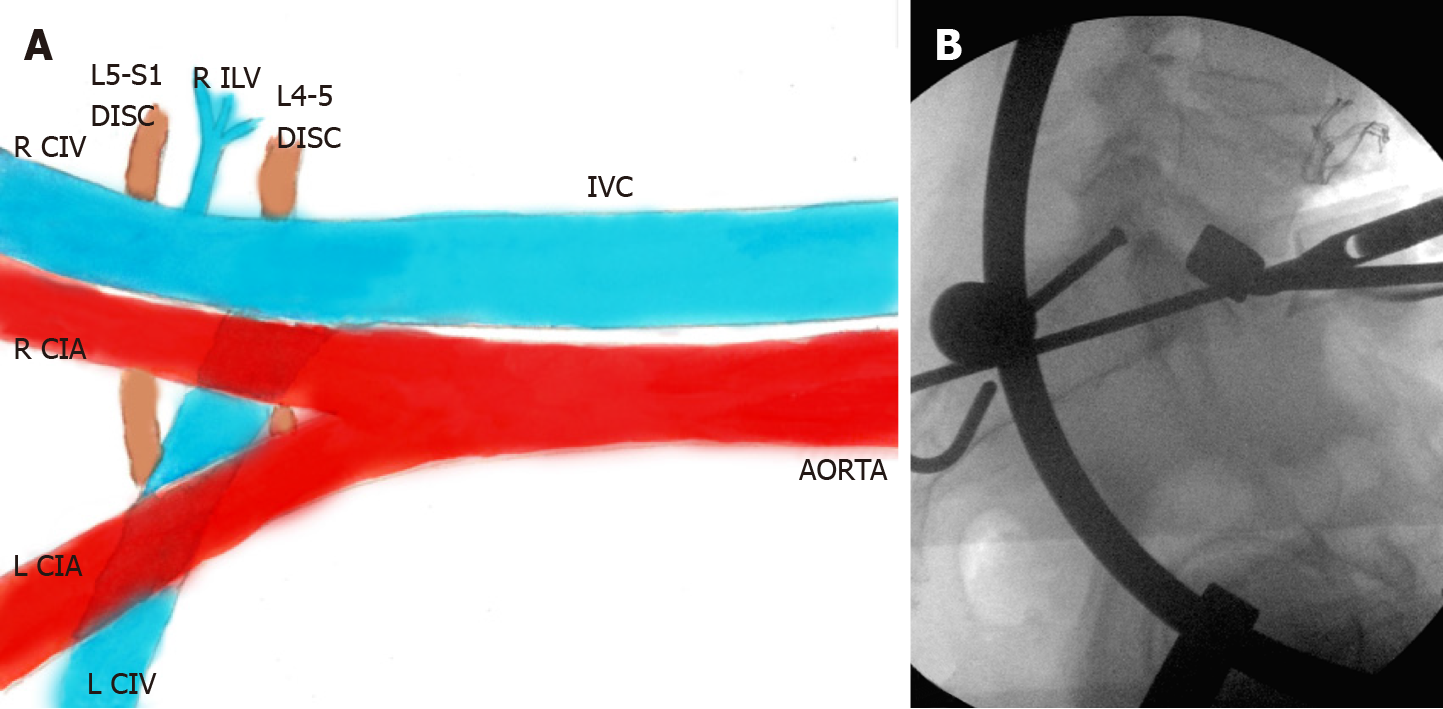

Right pre-psoas approach: The right pre-psoas approach is performed from the right side with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position and has been described by Tannoury et al[4] and others[13]. A transverse incision along the skin lines is made, as above. The procedure is similar to the aforementioned left pre-psoas approach in terms of muscle splitting, entering the retroperitoneal space, and retracting the peritoneal sac anteromedially. The right psoas and IVC are identified, and an interval is created between them. This interval is then traced inferiorly along the right CIV. The right L5 segmental vein, when present, is identified, ligated, and divided (Figure 4A). Next, the right CIV is carefully retracted anteromedially to expose the lateral annulus of the L5-S1 disc. Discectomy, endplate preparation, and placement of an LLIF cage is then performed using bent instruments (Figure 4B), similar to the left pre-psoas approach. While this approach has been found to be safe and feasible by previous studies[4,13], extensive experience and comfort level is required to work alongside the IVC.

Low back pain.

Case 1: A 58-year-old man [body mass index (BMI): 34 kg/m2] presented with longstanding back and leg pain refractory to conservative treatment.

Case 2: A 69-year-old man (BMI: 31 kg/m2) presented with longstanding back and leg pain refractory to conservative treatment.

Case 3: A 72-year-old man (BMI: 23 kg/m2) presented with longstanding back and leg pain refractory to conservative treatment.

Case 1 had undergone prior laminotomy surgery. Case 2 and Case 3 did not have any relevant past illness.

None of the 3 patients had any relevant positive personal and family history.

All 3 patients had examination findings consistent with Lumbar degenerative disc disease and stenosis. No neurologic deficit was noted. Case 2, in addition, showed findings consistent with a severe lumbar dextroscoliosis.

None of the 3 patients had any significant laboratory examination findings.

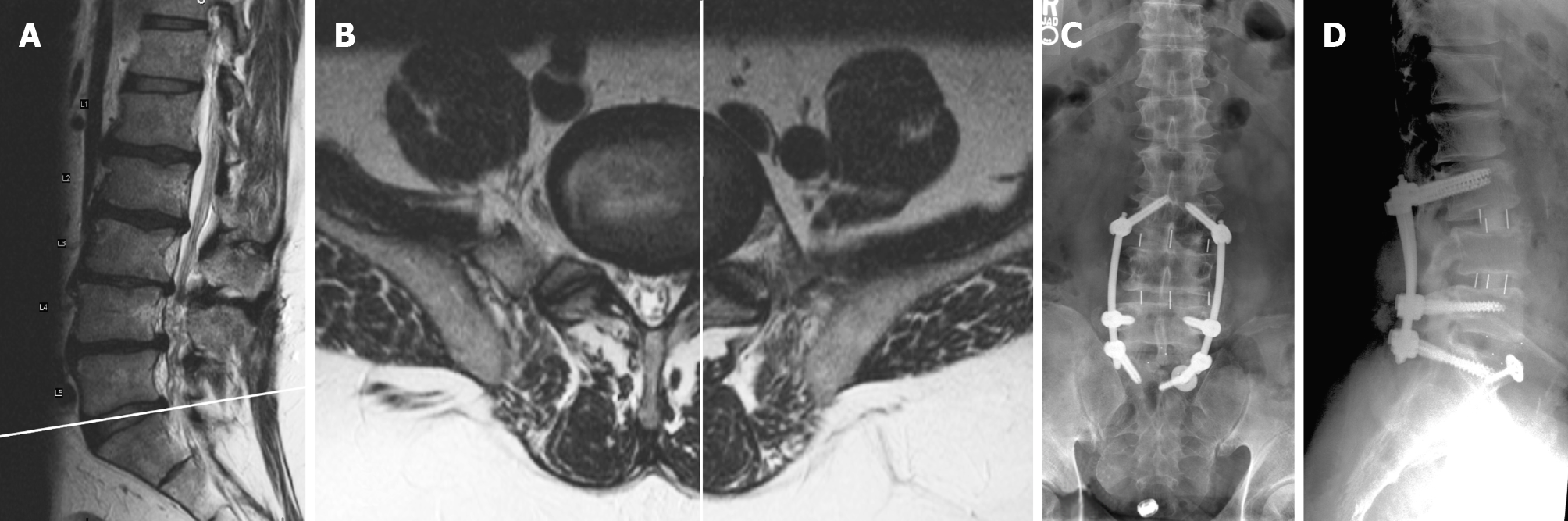

Case 1: He was found to have L3-S1 degenerative disc disease and stenosis (Figure 5). A careful review of all the available imaging revealed a wide intra-bifurcation interval between the left and right common iliac vessels in the axial section through the L5-S1 disc. There was an identifiable fat plane between the left CIV and the L5-S1 disc. The medial edge of the left CIV was lateral to the facet line (Figure 5B).

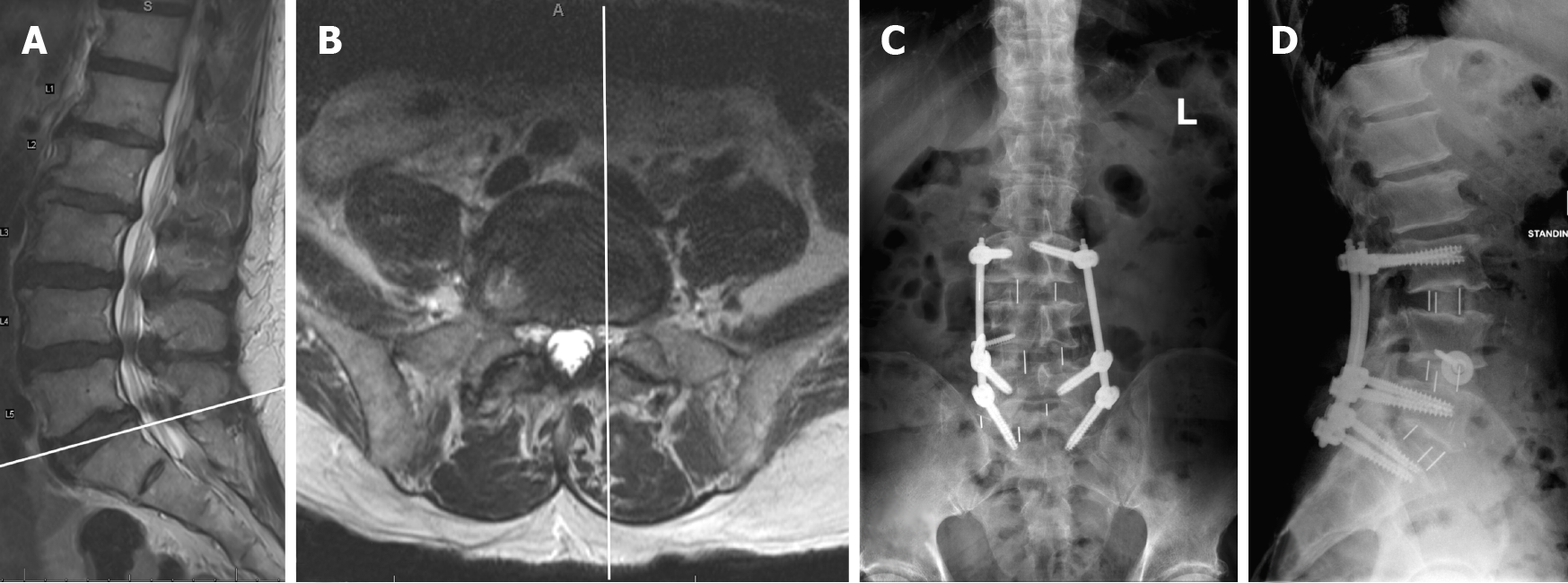

Case 2: He was found to have severe lumbar dextroscoliosis, sagittal imbalance, and multilevel stenosis (Figure 6). An MRI axial cut at the L5-S1 disc showed the left CIV in the midline with no obvious fat plane underneath it (Figure 6D).

Case 3: He was found to have L3-S1 degenerative disc disease with central & foraminal stenosis. L3-S1 OLIF with posterior PPSI was recommended. A thorough evaluation of preoperative imaging was performed (Figure 7). As seen on the L5-S1 disc axial MRI cut, the medial wall of the left CIV was medial to the facet line (Figure 7B). The fat plane was not well-visualized between the left CIV and L5-S1 disc, but a small fat plane was identifiable between the right CIV and L5-S1 disc.

Case 1: L3-S1 degenerative disc disease and stenosis.

Case 2: Severe lumbar dextroscoliosis, sagittal imbalance, and multilevel stenosis.

Case 3: L3-S1 degenerative disc disease and stenosis.

Case 1: L3-S1 OLIF with posterior percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation (PPSI) was recommended. L5-S1 was approached through the left intra-bifurcation approach, and L3-4 and L4-5 through the left pre-psoas interval, all through the same incision. Minimal retraction and careful protection of the left common iliac vessels was required. Median sacral vessels were ligated. Posterior percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation was performed in the prone position in the same operative setting. Neuromonitoring was not utilized. Operative time was 358 minutes, and intra-operative blood loss was 100 mL. No vascular injuries and no perioperative blood transfusions were required.

Case 2: Staged L1-S1 OLIF followed by posterior T11-S1 PPSI and iliac fixation on the next day was recommended. A left-sided pre-psoas approach was performed. During the exposure of L5-S1, minimal retraction of the left common iliac artery and no retraction of the CIV were required. The left ILV was not identified and did not interfere with exposure. A single skin incision provided access to 5 spinal segments from L1-S1, taking advantage of the scoliotic concavity on the left side. The patient underwent posterior instrumentation the next day, as planned. Neuromonitoring was used during the second stage only. Operative times for the two stages was 262 min and 294 min, and intra-operative blood loss was 500 mL and 250 mL, respectively. A minor vascular injury in the form of segmental bleed was encountered while exposing the L2-3 disc anterolaterally, which was controlled with ligation. No perioperative blood transfusions were required.

Case 3: L3-S1 OLIF with posterior PPSI was recommended. A right-sided pre-psoas approach was performed with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position. While accessing L5-S1, an L5 segmental vein was encountered, which was ligated with vascular clips and divided. Posterior PPSI was performed with the patient in the prone position at L3-S1 in the same operative setting. Neuromonitoring was not used. Operative time was 278 min, and intra-operative blood loss was 100 mL.

Case 1: The patient recovered well and was discharged home on postoperative day 2. Transient left groin pain was reported but resolved by the 2-wk follow-up. No other approach-related complications were observed. The patient reported excellent clinical improvement at his one year follow up visit. No subsidence or pseudarthrosis was seen.

Case 2: Excellent recovery was seen postoperatively, and the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility on day 6. He showed no approach-related complications. The patient reported excellent clinical improvement and radiographic maintenance of alignment at his two year follow up visit. No subsidence, pseudarthrosis, hardware failure, or proximal junctional issues were seen.

Case 3: The patient recovered well and was discharged home on postoperative day 2. There were no approach-related complications reported. The patient reported excellent clinical improvement at his one year follow up visit. No subsidence or pseudarthrosis was seen.

Lumbar interbody fusion techniques via anterior approaches (ALIF, OLIF, and LLIF) provide opportunities for indirect decompression[18] and better correction of lordosis than posterior techniques[19]. Among these approaches, OLIF/ATP shows the greatest versatility, allowing exposure of nearly all lumbar levels from T12-S1[4], and provides distinct advantages over other anterior and posterior approaches with favorable complication profiles[9,10]. Neuromonitoring is not considered essential[4,5,18] as the psoas muscle cushions the lumbar plexus during retraction. Intraoperative muscle relaxation can be employed with favorable effects on abdominal wall musculature compliance, psoas retractability[20], and intra-abdominal pressure.

Complication rates in OLIF/ATP approaches have been reported between 7.2% and 48.3% in different studies[4,21-23]. The incidence of certain complications may be higher when L5-S1 is included in the OLIF/ATP procedure[7,13,23]. This is especially true for vascular injuries, which can be catastrophic and potentially fatal. In a series of 940 patients, Tannoury et al[4] found vascular injuries in 0.3%. They approached L5-S1 via the left or right pre-psoas approaches. Woods et al[7] reported a 2.9% incidence of vascular injuries in their series of 137 patients. This incidence went up to 4.3% when L5-S1 was included in the approach. They used the intra-bifurcation approach to L5-S1. Our previously published series did not show any differences in incidence of vascular injuries between the three approaches to L5-S1[13]. Approach-related complications like ileus, ipsilateral groin pain, anterior thigh numbness or pain, incisional hernia, or pseudohernia have also been reported with the OLIF/ATP approach[4,7,12,23]. Subsidence may be seen more often with the OLIF approach compared to other anterior approaches for interbody fusion, according to Woods et al[7].

The intra-bifurcation left-sided approach is a modification of an ALIF approach to L5-S1, which most spine surgeons are accustomed to. It utilizes an oblique trajectory through an anterolaterally placed incision with the insertion of an ALIF cage. This approach allows broad access to the anterior aspect of L5-S1, which permits near-complete resection of the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL). Thus, better correction of lordosis can be achieved by utilizing a hyper-lordotic cage. This extensive ALL release may prompt the surgeon to place a plate or washer that covers the cage, to prevent the cage from dislodging anteriorly.

The intra-bifurcation approach may require careful retraction and mobilization of a flat left CIV that may be covering the left half of the L5-S1 disc[24] (Figure 3A). While this approach is similar to the supine ALIF approach, there is a higher likelihood of needing retraction or mobilization of the left CIV than the latter due to the left-sided oblique trajectory. This increases the risk of vascular injury as the medial aspect of the left CIV is often flat and stretched over the anterior osteophytes of the L5-S1 disc[13]. Additionally, in patients with a large sacral slope, a longer oblique incision extending far inferiorly may be required to align with the plane of the L5-S1 disc (Figure 2). In such instances, preparation of the L5 inferior endplate may be blind, requiring extensive help from fluoroscopy[15] (Figure 3B). Such blind endplate preparations might be common to all oblique approaches to L5-S1 and may be a reason for subsidence seen in some patients. Furthermore, due to the lower incision for L5-S1, separate incisions may be required to reach upper lumbar levels in multilevel surgeries. Midline orientation may also be challenging in the initial cases[7], because of the oblique trajectory of this approach. Lastly, the superior hypogastric sympathetic plexus, which lies anterior to the L5-S1 disc may still be at risk of injury with this approach.

The left and right pre-psoas approaches are an inferior continuation of the pre-psoas approach for levels above L5. Although the common iliac vessels are especially close to the psoas at L5-S1, this interval may be widened by retraction of the psoas and careful mobilization of the CIV, as needed. Being able to put a laterally-placed LLIF cage at L5-S1 reduces the need for longer skin incisions to align with the L5-S1 plane.

The left and right prepsoas approaches may be challenging in patients with large bulky psoas muscles. These approaches require specialized bent intruments and preparation of the L5 inferior endplate is often blind (Figure 3C, D and 4B). A blunt release of the contralateral annulus, which is common for OLIF or LLIF techniques at levels above L5, may not be advisable for the L5-S1 Level because of more laterally located contralateral common iliac vessels that may inadvertently get injured. ALL release is often not possible, however, a blunt ALL rupture may be achievable.

The right prepsoas approach may be useful in patients that may have a favorable indication to approach multiple levels from the right side; for example, in patients with a scoliotic concavity to the right, in those with prior left-sided abdominal surgeries with anticipated scarring, or in those with vascular anomalies[25]. This approach may also be used if the access surgeon believes that L5-S1 can be reached with greater safety than the other approaches[4]. However, this approach needs significant experience as the IVC and right CIV are approached head-on, and the prepsoas interval is much narrower at all levels on the right side.

Most patients could possibly undergo L5-S1 OLIF through more than one of the approaches described above. The choice should depend on the access surgeon’s comfort level and experience. However, the anatomic relationship of the left CIV to the L5-S1 disc may also be an important consideration. A wide anterior interval between the left and right CIVs, and a more lateral position of the left CIV (Patient 1) may favor an intra-bifurcation approach[13,26]. Although other methods of assessing the relative position of the left CIV to the L5-S1 disc are available[26], the facet line may be an easy, quick method[13]. If the medial border of the left CIV is medial to this facet line without a distinct fat plane underneath, the intra-bifurcation approach may be challenging, and a pre-psoas approach may be considered (Cases 2, 3). In such cases, the authors personally prefer a right-sided pre-psoas approach for the following reasons. The right CIV is somewhat vertical and is visible throughout its course in a right-sided approach, while the left CIV takes a more horizontal oblique course and is often hidden underneath its accompanying artery in left-sided approaches[24] (Figure 3A and 4A). In the authors’ experience, the more vertical right CIV is far more predictable in its course and easier to retract medially due to its rounded lateral edge, unlike the oblique and flat left CIV (Figure 7B). Moreover, according to Tannoury et al[4], the right ILV tends to be longer in length and smaller in caliber than the left ILV. The right ILV is hence easier to ligate and divide. Careful assessment of MRI axial images through the L5 vertebral body, may help identify L5 segmental veins or ILV on either side[4] (Figure 1C).

The left pre-psoas approach may be beneficial in anatomy as in Patient 2, where the bifurcation is at a relatively lower vertebral level, such that the left CIV may not need any retraction or mobilization. The left pre-psoas approach can also be potentially used as an intraoperative bailout when an intra-bifurcation approach is unsuccessful due to difficulty retracting the left CIV laterally[13]. However, the right prepsoas approach has to be chosen prior to surgery and cannot be used as an intraoperative bailout.

Altogether, L5-S1 can be exposed via an oblique approach using three different techniques, the choice of which may be customized according to a patient’s anatomy. A significant learning curve may be involved, and experience with identifying and ligating venous structures through mini-open exposures is required to safely perform these procedures. The availability of an experienced access surgeon is critical and may be essential for such exposures. While the right-sided pre-psoas approach has been shown to be safe and feasible in some studies, we strongly recommend gaining adequate experience before adopting this technique. In early cases and in patients with challenging vascular anatomy, posterior alternatives may be considered.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu P, Uçar BY S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Molloy S, Butler JS, Benton A, Malhotra K, Selvadurai S, Agu O. A new extensile anterolateral retroperitoneal approach for lumbar interbody fusion from L1 to S1: a prospective series with clinical outcomes. Spine J. 2016;16:786-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cahill KS, Martinez JL, Wang MY, Vanni S, Levi AD. Motor nerve injuries following the minimally invasive lateral transpsoas approach. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cummock MD, Vanni S, Levi AD, Yu Y, Wang MY. An analysis of postoperative thigh symptoms after minimally invasive transpsoas lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tannoury T, Kempegowda H, Haddadi K, Tannoury C. Complications Associated With Minimally Invasive Anterior to the Psoas (ATP) Fusion of the Lumbosacral Spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44:E1122-E1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Lee HJ, Ryu KS, Hur JW, Seong JH, Cho HJ, Kim JS. Safety of Lateral Interbody Fusion Surgery without Intraoperative Monitoring. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Davis TT, Hynes RA, Fung DA, Spann SW, MacMillan M, Kwon B, Liu J, Acosta F, Drochner TE. Retroperitoneal oblique corridor to the L2-S1 intervertebral discs in the lateral position: an anatomic study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21:785-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Woods KR, Billys JB, Hynes RA. Technical description of oblique lateral interbody fusion at L1-L5 (OLIF25) and at L5-S1 (OLIF51) and evaluation of complication and fusion rates. Spine J. 2017;17:545-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brau SA. Mini-open approach to the spine for anterior lumbar interbody fusion: description of the procedure, results and complications. Spine J. 2002;2:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jin J, Ryu KS, Hur JW, Seong JH, Kim JS, Cho HJ. Comparative Study of the Difference of Perioperative Complication and Radiologic Results: MIS-DLIF (Minimally Invasive Direct Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion) Versus MIS-OLIF (Minimally Invasive Oblique Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion). Clin Spine Surg. 2018;31:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xi Z, Burch S, Chang C, Ruan H, Eichler CM, Mummaneni PV, Chou D. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) vs oblique lateral interbody fusion (OLIF) at L5-S1: A comparison of two approaches to the lumbosacral junction. Neurosurgery. 2019;66:nyz310_336. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mayer HM. A new microsurgical technique for minimally invasive anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:691-9; discussion 700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Silvestre C, Mac-Thiong JM, Hilmi R, Roussouly P. Complications and Morbidities of Mini-open Anterior Retroperitoneal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion in 179 Patients. Asian Spine J. 2012;6:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Berry CA, Thawrani DP, Makhoul FR. Inclusion of L5-S1 in oblique lumbar interbody fusion-techniques and early complications-a single center experience. Spine J. 2021;21:418-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim JS, Sharma SB. How I do it? Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2019;161:1079-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pham MH, Jakoi AM, Hsieh PC. Minimally invasive L5-S1 oblique lumbar interbody fusion with anterior plate. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;41 Video Suppl 1:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zairi F, Sunna TP, Westwick HJ, Weil AG, Wang Z, Boubez G, Shedid D. Mini-open oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) approach for multi-level discectomy and fusion involving L5-S1: Preliminary experience. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chung NS, Jeon CH, Lee HD. Use of an Alternative Surgical Corridor in Oblique Lateral Interbody Fusion at the L5-S1 Segment: A Technical Report. Clin Spine Surg. 2018;31:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fujibayashi S, Hynes RA, Otsuki B, Kimura H, Takemoto M, Matsuda S. Effect of indirect neural decompression through oblique lateral interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40:E175-E182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Champagne PO, Walsh C, Diabira J, Plante MÉ, Wang Z, Boubez G, Shedid D. Sagittal Balance Correction Following Lumbar Interbody Fusion: A Comparison of the Three Approaches. Asian Spine J. 2019;13:450-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Woods K, Fonseca A, Miller LE. Two-year Outcomes from a Single Surgeon's Learning Curve Experience of Oblique Lateral Interbody Fusion without Intraoperative Neuromonitoring. Cureus. 2017;9:e1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Abe K, Orita S, Mannoji C, Motegi H, Aramomi M, Ishikawa T, Kotani T, Akazawa T, Morinaga T, Fujiyoshi T, Hasue F, Yamagata M, Hashimoto M, Yamauchi T, Eguchi Y, Suzuki M, Hanaoka E, Inage K, Sato J, Fujimoto K, Shiga Y, Kanamoto H, Yamauchi K, Nakamura J, Suzuki T, Hynes RA, Aoki Y, Takahashi K, Ohtori S. Perioperative Complications in 155 Patients Who Underwent Oblique Lateral Interbody Fusion Surgery: Perspectives and Indications From a Retrospective, Multicenter Survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42:55-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abed Rabbo F, Wang Z, Sunna T, Newman N, Zairi F, Boubez G, Shedid D. Long-term complications of minimally-open anterolateral interbody fusion for L5-S1. Neurochirurgie. 2020;66:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xi Z, Burch S, Mummaneni PV, Mayer RR, Eichler C, Chou D. The effect of obesity on perioperative morbidity in oblique lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2020;1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Capellades J, Pellisé F, Rovira A, Grivé E, Pedraza S, Villanueva C. Magnetic resonance anatomic study of iliocava junction and left iliac vein positions related to L5-S1 disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1695-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Berry CA. Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion in Patient with Persistent Left-Sided Inferior Vena Cava: Case Report and Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chung NS, Jeon CH, Lee HD, Kweon HJ. Preoperative evaluation of left common iliac vein in oblique lateral interbody fusion at L5-S1. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:2797-2803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |