Published online Mar 18, 2021. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i3.94

Peer-review started: November 23, 2020

First decision: December 24, 2020

Revised: December 29, 2020

Accepted: January 28, 2021

Article in press: January 28, 2021

Published online: March 18, 2021

Processing time: 106 Days and 22.9 Hours

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic on March 11, 2020. COVID-19 is not the first infectious disease to affect Trinidad and Tobago. The country has faced outbreaks of both Chikungunya and Zika virus in 2014 and 2016 respectively. The viral pandemic is predicted to have a significant impact upon all countries, but the healthcare services in a developing country are especially vulnerable. The Government of Trinidad and Tobago swiftly established a parallel healthcare system to isolate and treat suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19. Strick ‘lockdown’ orders, office closures, social distancing and face mask usage recommendation were implemented following advice from the WHO. This approach has seen Trinidad and Tobago emerge from the second wave of infections, with the most recent Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker report indicating a favourable risk of openness index for the country. The effects of the pandemic on the orthopaedic services in the public and private healthcare systems show significant differences. Constrained by shortages in personal protective equipment and inadequate testing facilities, the public system moved into emergency mode prioritizing the care of urgent and critical cases. Private healthcare driven more by economic considerations, quickly instituted widespread safety measures to ensure that the clinics remained open and elective surgery was not interrupted. Orthopaedic teaching at The University of the West Indies was quickly migrated to an online platform to facilitate both medical students and residents. The Caribbean Association of Orthopedic Surgeons through its frequent virtual meetings provided a forum for continuing education and social interaction amongst colleagues. The pandemic has disrupted our daily routines leading to unparalleled changes to our lives and livelihoods. Many of these changes will remain long after the pandemic is over, permanently transforming the practice of orthopaedics.

Core Tip: A government-led disciplined response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an essential component in the fight against this pandemic. Orthopedic surgeons have been at the forefront of the struggle, maintaining essential surgical services while ensuring the safety of the public. Developing countries with under-resourced healthcare facilities have fared far better than many developed countries. In this war against COVID-19 the resilience and innovative spirit of the people may be our most effective weapons.

- Citation: Mencia MM, Goalan R. COVID-19 and its effects upon orthopaedic surgery: The Trinidad and Tobago experience. World J Orthop 2021; 12(3): 94-101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v12/i3/94.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i3.94

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 was first reported from Hubei province of the People’s Republic of China in December 2019[1,2]. This highly infectious pathogen named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) rapidly spread throughout many countries, compelling the World Health Organisation to declare it a pandemic on March 11, 2020[3,4].

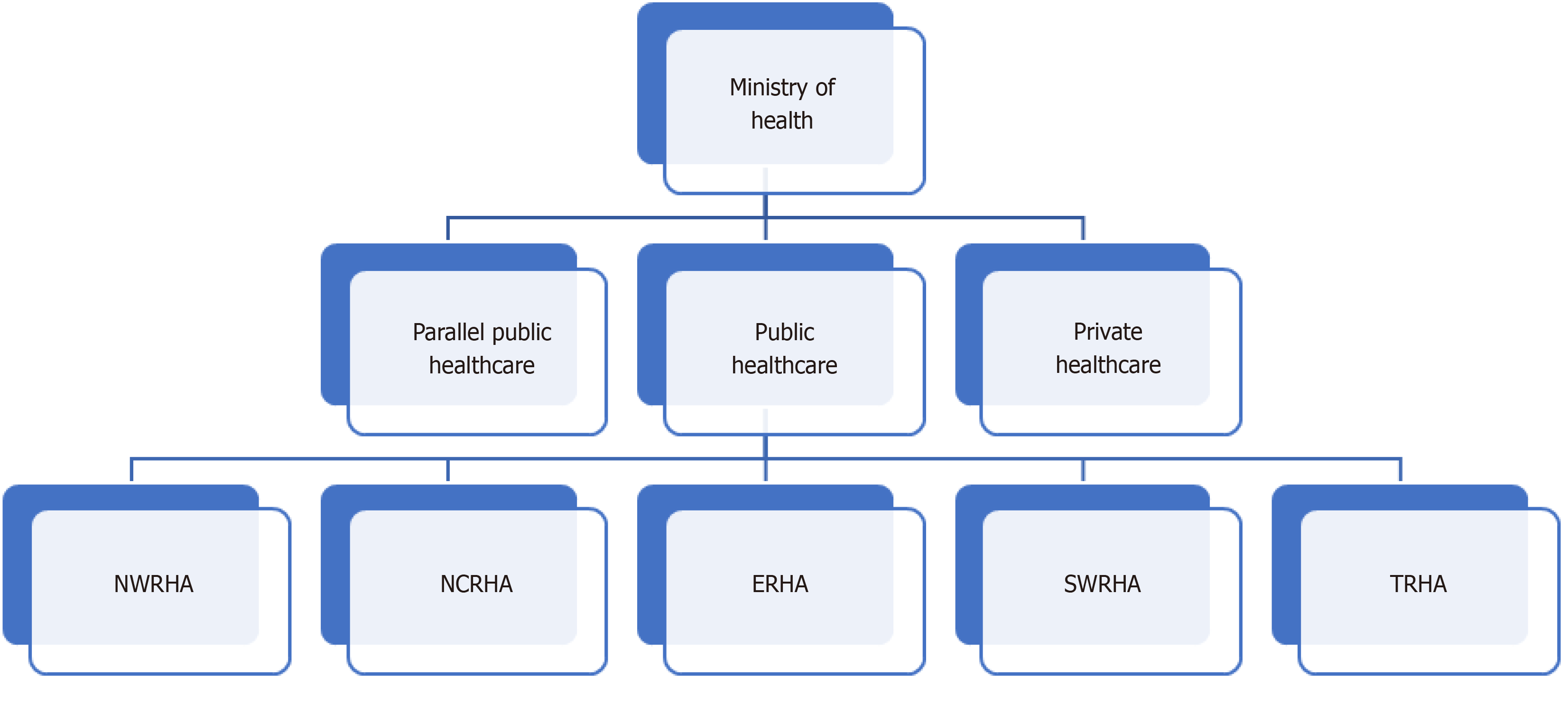

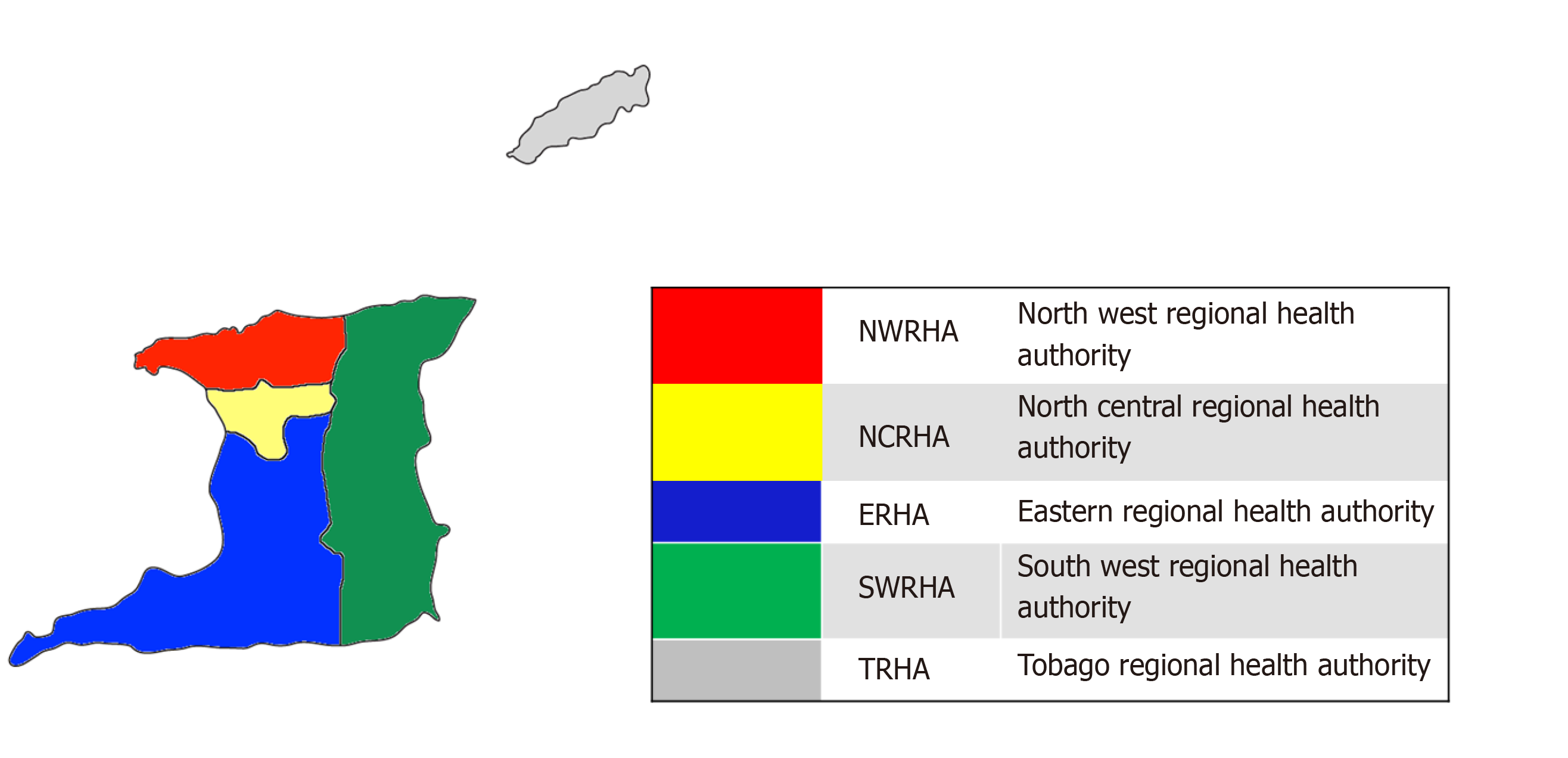

The beautiful islands of the Caribbean have not been spared the effects of COVID-19 with Trinidad and Tobago reporting its first case on March 12, 2020[5]. The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago is a twin-island state covering 1980 sq miles and located just 6.8 miles off the coast of northeastern Venezuela. Classified as a developing country, it has a population of 1363985 and is world-renowned for its colorful carnival, steelpan and Pitch Lake[6]. The healthcare system of Trinidad and Tobago includes both public and private sectors (Figure 1). Public healthcare is centrally funded, delivering its services, free at the point of access through five Regional Health Authorities; conversely the private sector operates on a fee for service basis[7,8] (Figure 2).

The response from the Government of Trinidad and Tobago (GoRTT) to the virus was quick and decisive, with infected cases and those persons exposed being placed in state quarantine. The country’s international borders were closed on March 22, 2020 and a national stay-at-home order put in place from March 30, 2020, resulting in a “lockdown” of the country. A parallel public health system consisting of separate and independent tiered medical facilities, staff and laboratories was established to treat persons in state quarantine, while allowing the normal public health system to serve the needs of the rest of the population. These measures resulted in an initial flattening of the curve, and Trinidad and Tobago was ranked number one by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) in a report published by the University of Oxford on May 1, 2020[9].

In an attempt to restart the economy the Prime Minister announced plans to lift restrictions on a six-tier phased basis beginning on May 10, 2020. The announcement of General Elections on July 3, 2020 signaled the start of an intense election campaign, marred by numerous breaches of the public health safety protocols. Leading up to Election Day, there was a gradual increase in daily confirmed cases and on August 15, 2020, five days after elections, the Chief Medical Officer confirmed that there was now community spread of COVID-19 in Trinidad and Tobago[10].

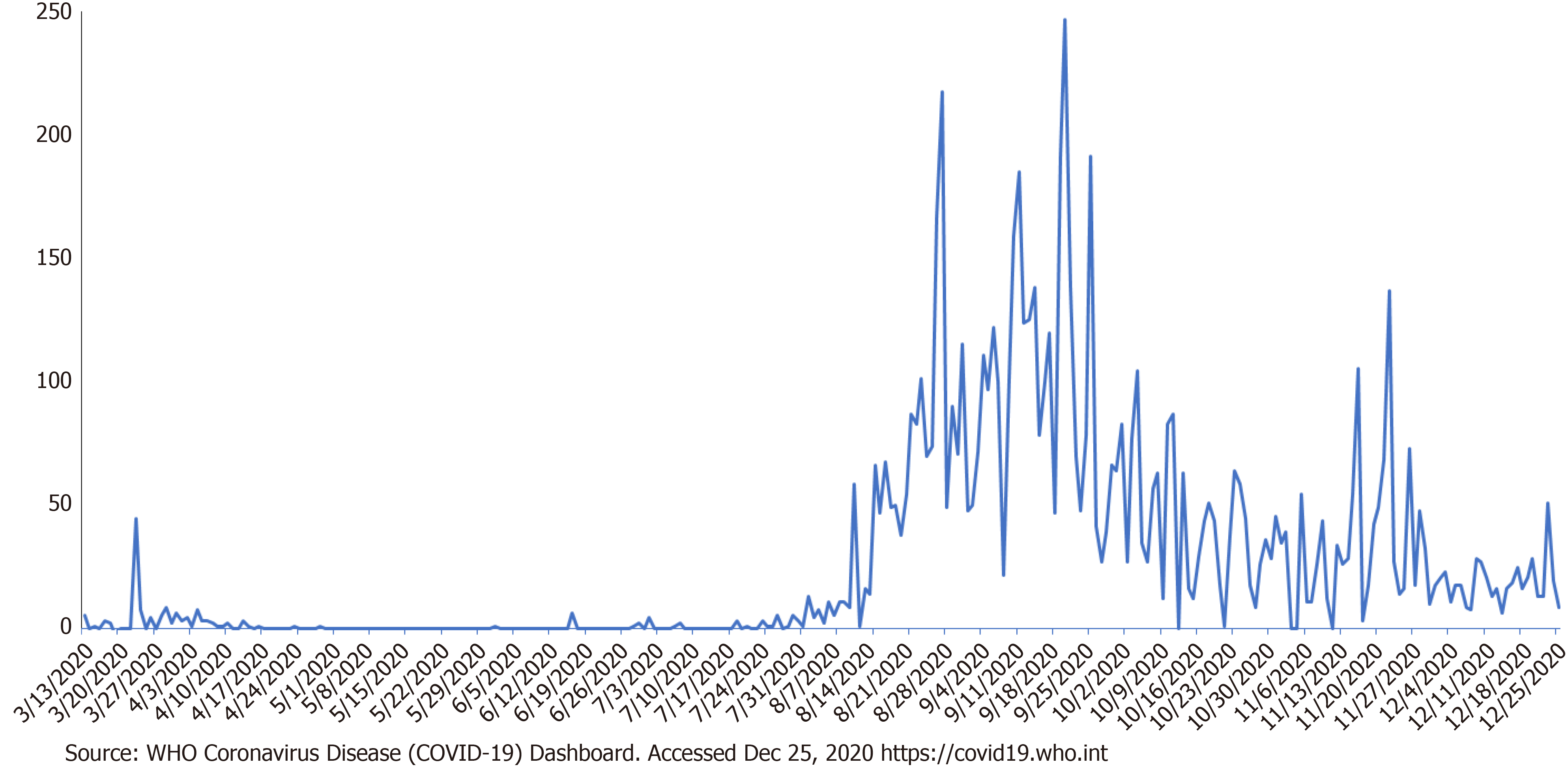

The GoRTT has maintained a lively response to the pandemic, with the OxCGRT derived Stringency Index trend for TnT mirroring the daily reported new cases of infection. At the time of writing we are emerging from the second wave of infections which started on July 20, 2020 with case 139, with a total of 7115 confirmed cases and 125 deaths (Figure 3). As our country returns to some semblance of normalcy we have seen a relaxation of the lockdown restrictions and our Risk of Openness Index (previously ‘Lockdown Rollback Checklist’) indicates a favorable environment to reopening[11].

With the arrival of the first case of COVID-19 on the shores of Trinidad and Tobago, we noted a drop in clinic attendance as patients tended to avoid the hospital environment for fear of becoming infected. In addition, to reduce unnecessary crowding in the clinics, only patients requiring urgent consultation or follow up were given appointments. The patient medical records and referral letters were screened to identify such patients considered as high priority cases, which mostly consisted of patients with fractures, infections and cases of malignancy.

In accordance with public health recommendations, high visibility physical distancing signage was placed in the clinic waiting area and patients were required to wear face masks and wash their hands before being seen. Appointments in 20 min slots were also instituted to allow separation of persons by time. Only one family member was permitted to accompany a patient and children were not allowed in the clinic. Before entering the consultation room each patient had their temperature taken with an infrared scanner and medical personnel wore face masks and/or face shields during consultation. To further reduce patient traffic in the hospital, only essential imaging was requested and patients were encouraged to practice home based physical therapy. All non-urgent surgery was postponed and temporary measures such as steroid injections and splints were used where applicable.

The national priority was to provide, at a minimum, basic orthopaedic services to the general community. Within the public sector the orthopaedic service is delivered by independently functioning teams. From the start, cross infection between teams of surgeons was identified as a major threat with the potential to destabilise our clinical infrastructure. To reduce risk we avoided unnecessary interaction between staff members of different teams, using electronic methods of communication e.g., WhatsApp® for patient handovers and cancelling several departmental meetings including grand rounds and journal club presentations.

In the first wave of the pandemic, large numbers of COVID-19 positive cases and limited supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) made it difficult to maintain the surgical services. To conserve scarce resources the Minister of Health in consultation with the Chief Medical Officer announced a temporary halt to all elective surgery in public hospitals on March 15, 2020[12]. To facilitate urgent and emergency cases, many surgeons purchased their PPE for use within the public hospital.

We are presently coming out of the second wave which has been characterised by community spread and rising mortality. To protect the healthcare workers, all patients, except those requiring immediate life-saving measures, must have a negative COVID-19 reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test before undergoing surgery. Elective surgery has resumed although many lists have been cancelled due to a delay in obtaining tests results.

The effect of the pandemic on the private sector differed from the public sector in several ways. Most private clinics continued to function with patients being reassured that safety measures were in place. Outdoor hand washing facilities, the provision of hand sanitiser and face masks for patients and staff were some of the additional preventative measures implemented in the private sector. Overcrowding in the waiting area was managed by having patients remain in their vehicles until the doctor was ready to see them. Despite this, doctors’ practices reported low attendance rates with many appointments being cancelled.

As opposed to the public sector, there was a noticeable increase in the use of digital technology. Many practices took the opportunity to transition to a paperless office system, including the use of electronic payment to reduce interpersonal contact. Telemedicine for medical consultation was used infrequently, except by physical therapists where there has been early and wide adoption of the technology. A significant barrier to broader usage is the unavailability of a confidential and secure platform as well as an agreed billing and reimbursement method from payers[13].

With the predicted fall in revenue caused by the pandemic, many private hospitals introduced measures to preserve their financial viability. Critically, patient welfare was the priority, and hospital administrators established major safety precautions to encourage confidence in the private health care system. This strategy has been successfully used in cardiac surgery at one of the private hospitals in Trinidad[14]. Additionally, many surgical procedures were transitioned to the outpatient setting, with savings to both the patient and hospital while maintaining surgical volume. Furthermore, the widescale digital transformation has improved billing and administrative processes, which is anticipated to result in future cost savings. A surprising but welcome source of additional revenue has come from an increase in both laboratory tests and imaging studies as the public seeks to remain healthy in the face of a deadly pandemic. Despite all these challenges, at the time of writing, no private hospitals have closed.

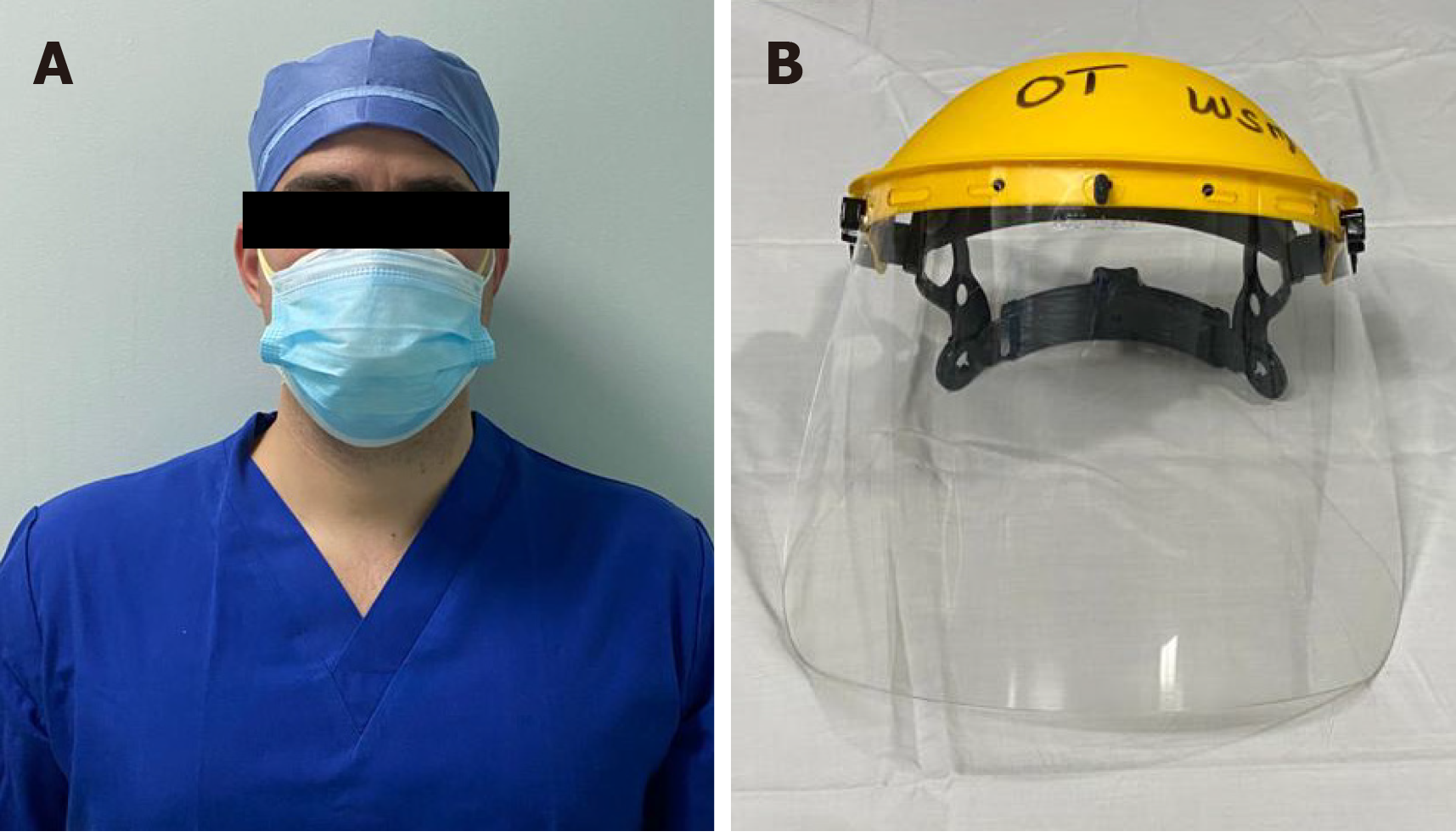

Most private hospitals derive the majority of their income from surgery, and unlike the situation in the public sector, elective surgery was encouraged. Initially, limited supplies of PPE in private hospitals led to some innovative methods to preserve stocks and protect staff. This included the use of industrial protective face shields and “double masking”, in which two face masks were used in combination: a standard surgical mask over an N95 respirator mask to protect the latter from becoming soiled with blood during surgery (Figure 4).

To maintain confidence in the private sector, compulsory COVID-19 PCR tests before elective surgery was implemented very early, with the use of dedicated testing facilities and staff (Figures 5 and 6). Emergency cases are admitted only after a negative COVID-19 immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgM antibody test and isolated from other inpatients. Unless urgent surgical intervention is required, these patients must also have a negative COVID-19 RT-PCR test preoperatively. Although the additional testing is both inconvenient and expensive, it has been well received by most patients who recognise the need for these safety measures.

Although several doctors have contracted COVID-19, to date there are no reports of COVID-19 related deaths amongst orthopaedic surgeons or COVID-19 related deaths or complications following orthopaedic surgery.

The University of the West Indies (UWI) is one of only two regional universities in the world and is currently ranked by the Times Higher Education as the Caribbean’s leading university[15]. The medical school of the Faculty of Medical Sciences (FMS) provides training for over 200 medical students who were affected by the pandemic. The FMS moved swiftly in response to the pandemic, ensuring that their teaching staff was well equipped to work in the new normal of online education, with workshops and webinars conducted by the Centre for Medical Sciences Education and the Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.

The four-week undergraduate orthopaedic clerkship has been reorganised into a two-week online course which focuses on the acquisition of core knowledge using didactic lectures, problem-based learning and group discussion. E-learning has been shown to be an enjoyable and effective method of teaching in some studies[16]. The method is however novel to medical education at UWI, specifically orthopaedics and is currently the subject of a study proposal which would give greater insight into its usefulness. (UWI Campus Research Ethics Committee Application CREC-SA.0511/09/2020). The online component is to be complemented by a two-week face-to-face clinically oriented course which began on November 8, 2020, in step with national conditions allowing for a safe return to the clinical setting.

Resident education has been significantly affected by the pandemic. The June/July 2020 exit examination has been postponed and the enrolment of new residents deferred until 2021. Teaching has continued online with the use of Zoom® following the suspension of face-to-face teaching. Of great concern is the diluted clinical exposure caused by a reduction in elective surgery and low outpatient clinic attendance. Additionally, the trauma burden from motor vehicle accidents and sports injuries is significantly reduced, a phenomenon likely related to the population being required to limit outdoor activity.

The FMS understands its pivotal role in supporting the healthcare workforce of Trinidad and Tobago and has had to weigh this with its obligation to provide a safe working environment for students. Continuous dialogue with stakeholders has produced a blueprint for the resumption of clinical teaching; the document which has the support of the Minister of Health has been granted an exception from the national mandate to suspend all teaching until 2021.

This short report on the effects of the pandemic upon the orthopaedic services of Trinidad and Tobago would be incomplete without mentioning The Caribbean Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons (TCOS). The association was founded in 2007 following an informal gathering of orthopaedic surgeons from the region, dubbed an “Orthopaedic Lime”. Used in this context “lime”, is a Trinidadian phrase meaning: to hang out or socialise in an informal relaxing environment especially with friends[17]. The executive of TCOS lost no time in responding to the pandemic. The discussion of clinical cases and the scientific concepts were promptly migrated to a social media platform. This rapidly developed into the hosting of monthly Clinical Symposia via Zoom, and a larger two-day event is planned for November 2020. These virtual meetings have been well attended, providing both educational opportunities as well as a space for mental restitution. The connection with colleagues, socialization and sharing of experiences, are essential activities for mental wellbeing, providing a much-needed respite during these difficult times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented effect upon the practice of orthopaedic surgery in Trinidad and Tobago. Amid the overwhelming negative impact of the pandemic, several noteworthy transformations have emerged. The rapid adoption of digital technologies in the workplace has improved efficiency, reduced waste and increased patient access to affordable healthcare. Similarly, the transition to online teaching has led to more consistent resident attendance and greater participation in discussion groups.

Surgeons have united in a spirit of teamwork and camaraderie as they face this novel viral threat. Hitherto unseen leadership qualities have emerged, with many examples of surgeons acting selflessly with courage, compassion and empathy. This COVID-19 pandemic will not last forever, but the role that we, as orthopaedic surgeons have played in facing the enemy will in perpetuity be part of our legacy.

Work safe, stay safe.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Trinidad and Tobago

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Deng B S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Asakawa J, Mohrenweiser HW. Characterization of two new electrophoretic variants of human triosephosphate isomerase: stability, kinetic, and immunological properties. Biochem Genet. 1982;20:59-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18987] [Cited by in RCA: 17639] [Article Influence: 3527.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Montgomery L, Macy JM. Characterization of rat cecum cellulolytic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:1435-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8473] [Cited by in RCA: 7596] [Article Influence: 1519.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kharchenko AP, Polishchuk NE, Usatov SA. [Changes in the cerebral circulation in patients with brain concussion sustained during alcoholic intoxication]. Vrach Delo. 1982: 75-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1106] [Cited by in RCA: 1074] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:157-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2621] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ministry of Health TnT. Statement from the Honourable Terence Deyalsingh, Minister of Health at the Media Conference to Advise of the First Confirmed (Imported) Case of COVID-19 in Trinidad and Tobago 2020. [Cited June 17, 2020]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.tt/sitepages/default.aspx?id=293. |

| 6. | Central Statistical Office. Provisional Mid-year Estimates of Population by Age Group and Sex, 2005-2019. [Cited August 15, 2020]. Available from: https://cso.gov.tt/subjects/population-and-vital-statistics/population/. |

| 7. | PAHO. Health in the Americas: Summary: Regional Outlook and Country Profiles. [Cited June 17, 2020]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/hearts-americas. |

| 8. | Ministry of Health TnT. Ministry of Health -Overview 2020. [Cited August 15, 2020]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.tt/sitepages/default.aspx?id=38. |

| 9. | Hale T, Phillips T, Petherick A, Kira B, Angrist N, Aymar K, Webster S. Version2.0- Lockdown Rollback Checklist: Do CVountries Meet WHO Recommendations for Rolling Back Lockdown? 2020. [Cited July 15, 2020]. Available from: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/2020-04-Lockdown-Rollback-Checklist-v2.pdf. |

| 10. | Kissoon C. T & T reaches Community Spread of Covid-19 2020. August 15, 2020 [Cited September 12, 2020]. Available from: https://trinidadexpress.com/newsextra/t-t-reaches-community-spread-of-covid-19/article_94fcad86-df28-11ea-aa23-0fbc1991242c.html. |

| 11. | Hale T, Petherick A, Kira B, Angrist N, Aymar K, Webster S, Majumdar S, Hallas L, Tatlow H, Cameron-Blake E. Risk of Openness index: When do government responses need to be increased or maintained? Blavatnik School of Government 2020 [Cited November 19, 2020]. Available from: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/10-2020-Risk-of-Openness-Index-BSG-Research-Note.pdf. |

| 12. | Rodriguez K. ‘I cancelled the elective surgeries’ 2020. May 13, 2020 [Cited September 12, 2020]. Available from: https://trinidadexpress.com/newsextra/i-cancelled-the-elective-surgeries/article_63971034-952b-11ea-aac8-93c6dc9e4fb9.html. |

| 13. | Mencia MM. Can outpatient total hip arthroplasty be safely performed in the Caribbean? Trop Doct. 2020;50:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ramsingh RAE, Duval JL, Rahaman NC, Rampersad RD, Angelini GD, Teodori G. Adult cardiac surgery in Trinidad and Tobago during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from a developing country. J Card Surg. 2020;1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | UWI News. The UWI’s “Triple Firsts” in latest Times Higher Education rankings UWI -TV2020. [Cited September 13, 2020]. Available from: https://uwitv.org/uwi-news/the-uwis-triple-firsts-in-latest-times-higher-education-rankings. |

| 16. | Warnecke E, Pearson S. Medical students' perceptions of using e-learning to enhance the acquisition of consulting skills. Australas Med J. 2011;4:300-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Urban Dictionary. Urban Dictionary 2020. [Cited July 13, 2020]. Available from: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=lime. |