Published online Dec 18, 2021. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i12.1008

Peer-review started: April 1, 2021

First decision: July 28, 2021

Revised: August 11, 2021

Accepted: December 7, 2021

Article in press: December 7, 2021

Published online: December 18, 2021

Processing time: 256 Days and 10.8 Hours

Development of infrapatellar saphenous neuroma (ISN) is a well-recognized reason for knee pain following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). So far, very few studies have addressed the development of painful ISN after TKA and its impact on functional outcome and patient satisfaction.

To present the results of surgical treatment for ISN after primary TKA, the level of pain relief, and the improvement of knee motion and function.

Fifteen patients (13 women, 2 men) with persistent medial pain for more than six months after primary TKA, due to osteoarthritis, underwent surgical excision of ISN. ISN diagnosis was confirmed with the presence of Tinel’s sign along the course of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve and with pain relief after selective nerve block using local anesthetic. Component loosening, malalignment, instability and infection were excluded systematically in all patients as a source of pain. Pain relief in terms of visual analog scale (VAS), active knee range of motion (ROM), and the Knee Society Score (KSS) for pain and function were evaluated preoperatively and at least six months postoperatively.

The mean patients’ age was 71.3 ± 5.4 years old. The mean interval between TKA and neuroma excision was 10 mo (range, 6 to 14 mo), while the mean follow-up was 8 mo (range: 6 to 11 mo). All 15 patients experienced almost complete immediate pain relief and resolution of allodynia and hyperesthesia after surgery. Pain on the VAS scale improved from 8.6 ± 1.3 preoperatively to 0.8 ± 0.9 at the final follow-up (P = 0.001). KSS pain and function scores were improved from 49.3 ± 5.9 and 62.7 ± 12.8 before surgery to 91.8 ± 4.2 and 75.3 ± 11.3 after surgery, respectively (P = 0.001 and P = 0.015). Active knee ROM was also increased postoperatively from 96 ± 4 to 105 ± 6 degrees (P = 0.001). There were no complications and no further operations required.

ISN should be considered a potential cause of persistent pain following TKA. Neuroma excision not only provides immediate pain relief and resolution of symptoms but may also improve the knee range of motion.

Core Tip: Development of infrapatellar saphenous neuroma after total knee arthroplasty should be considered a potential reason for persistent pain in an otherwise non-infected, well-fixed, and well-aligned joint. Before total knee arthroplasty, patients should be warned for the risk of nerve injury and neuroma formation. Neuroma excision provides excellent pain relief and improves knee function and range of motion.

- Citation: Chalidis B, Kitridis D, Givissis P. Surgical treatment outcome of painful traumatic neuroma of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve during total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop 2021; 12(12): 1008-1015

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v12/i12/1008.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i12.1008

Postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a complex and multifactorial issue. Infection, loosening, instability, component malalignment, poor ligament balance, and complex regional pain syndrome may lead to knee pain, stiffness, and poor functional outcome[1,2].

Although very rare, the development of infrapatellar saphenous neuroma (ISN) is a well-recognized factor of knee pain following not only TKA but also patellar and hamstring tendon harvest during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, open and arthroscopic repairs, tibial nailing, and vascular surgery of the lower extremity[3,4]. The prevalence of postoperative infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve (IPSN) damage has been reported to range between 0.5 to 53%[4] and may be apparent up to 9.7% and 21% of patients after primary and revision TKA, respectively[5], causing neuralgia or hypersensitivity, paresthesia, and loss of sensation at the medial joint area[4].

The IPSN is a purely sensory nerve that derives from the saphenous nerve. The latter arises as a division of the femoral nerve and leaves the adductor canal between the tendons of gracilis and semitendinosus[6]. It then divides into the main saphenous branch, which continues down to the ankle, and the IPSN that crosses the inferior knee from medial to lateral and innervates the skin below the patella as well as the anterior inferior knee capsule[3]. During TKA, the nerve is inevitably sectioned during the midline skin incision and anteromedial approach. Medial retractors, knee position in flexion, and a thigh tourniquet may further increase the tension over the course of the nerve and impede uneventful recovery[7]. Although the area of postoperative hypesthesia at the distribution of IPSN is usually decreased during the time, a painful neuroma can occur and further surgical intervention may be required[8]. The risk is even higher when the nerve is traumatized close to its origin and before its terminal branches[9].

So far, very few studies have addressed the issue of the development of painful ISN after TKA, and no clear evidence regarding its importance on functional outcome and patient satisfaction exists. In the current clinical study, we present the results of surgical treatment of ISN after primary TKA. The level of pain relief and improvement of knee motion and function are also described.

Between 2012 and 2018, 2054 patients underwent primary TKA due to osteoarthritis in our department. Patients with previous open knee operations and skin incisions were excluded from further evaluation. All operations were performed using a thigh tourniquet and a standard midline skin incision with a medial parapatellar knee approach were applied. Twenty-nine patients (1.4%) complained of postoperative medial knee pain that was frequently accompanied by burning and tingling sensation, hyperesthesia, and allodynia after the index procedure.

All patients were evaluated with X-Rays, computed tomography (CT) scan, and bone scan to exclude any component malalignment and/or implant failure. Infection was also ruled out performing erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein blood tests as well as knee aspiration. The joint fluid sample was sent to laboratory for culture and evaluation of synovial white blood (WBC) and its proportion of polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells according to the criteria for the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection as proposed by the Musculoskeletal Infection Society and the International Consensus Meeting[10]. WBC > 3.000 cells/μL and PMN > 80% were considered indicative for knee infection and additional diagnostic and operative procedures were performed[10].

The diagnosis of ISN was based on the presence of Tinel’s sign along the course of IPSN and confirmed with an injection of 1 mL lidocaine 1% and 2 mL ropivacaine 0.2%. In case of pain relief, the patient was suggested to follow a protocol that included injection with betamethasone acetate/betamethasone sodium phosphate (Celestone Chronodose) at the neuroma site and pregabalin intake (50 mg or 75 mg three times per day).

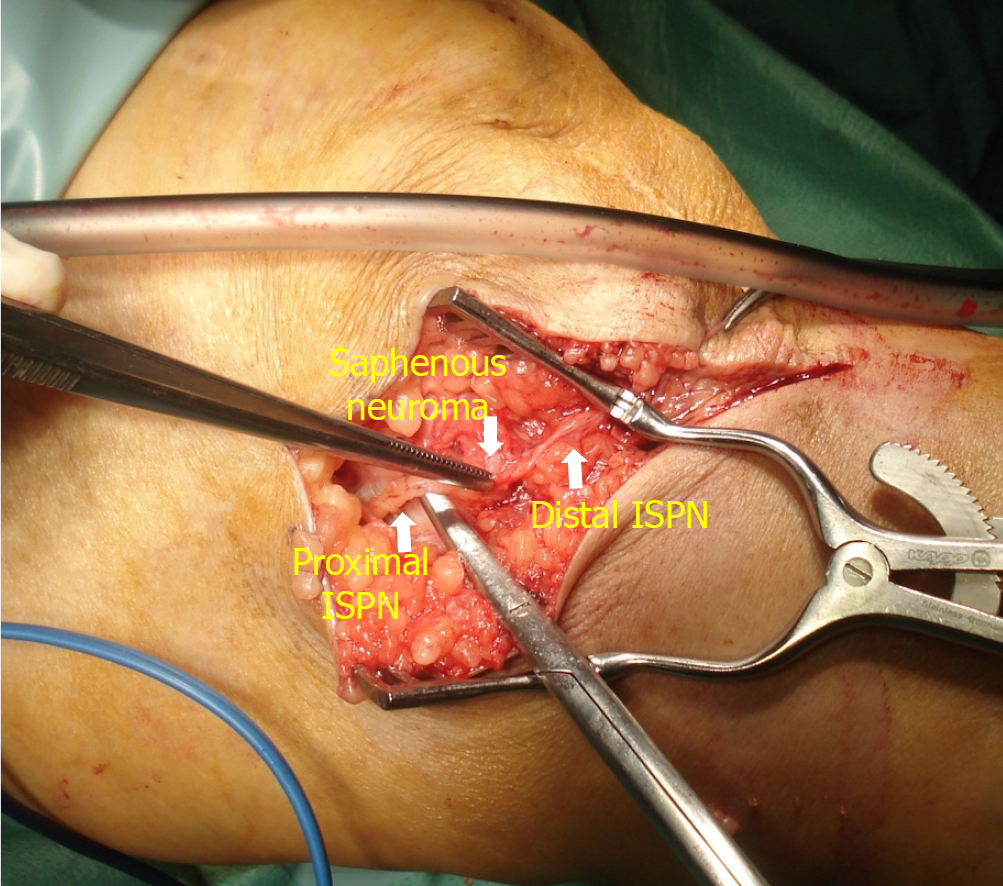

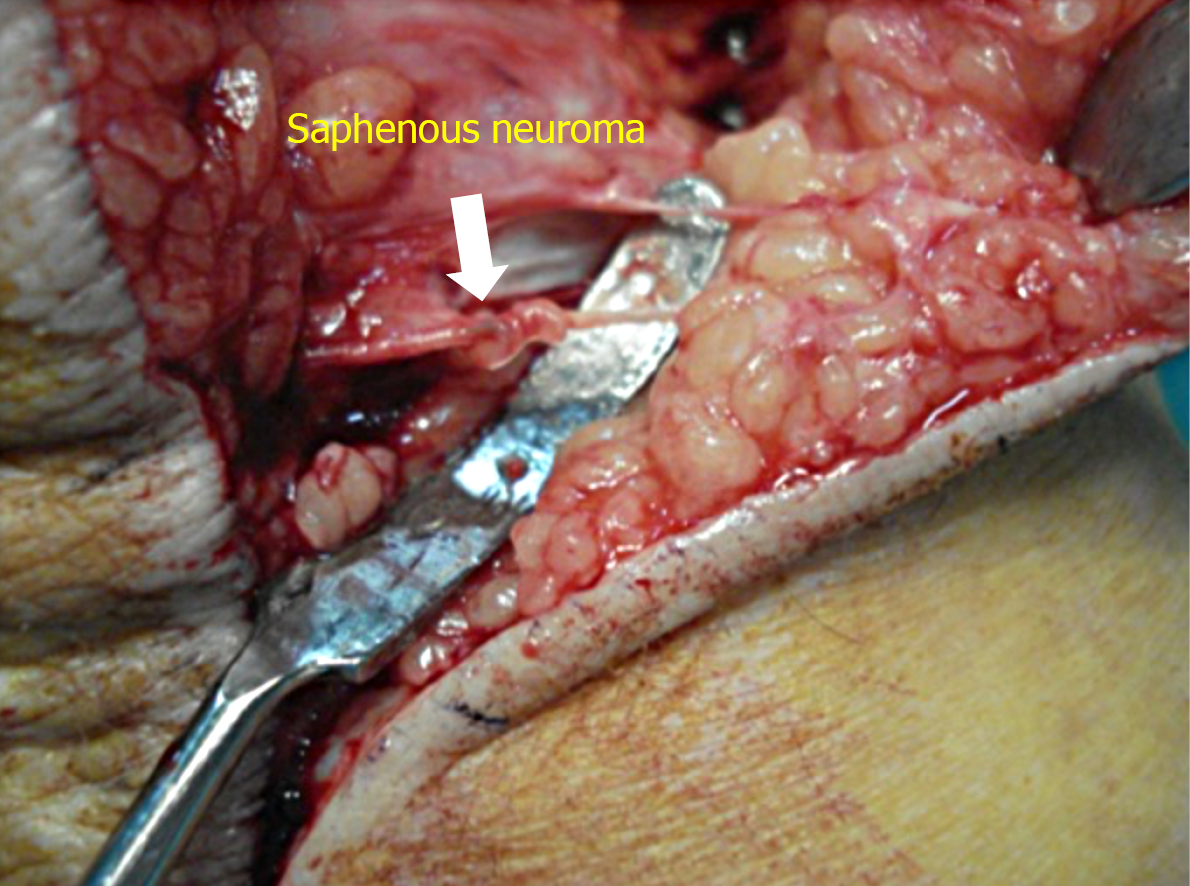

Fifteen patients (13 women, 2 men) failed to respond to conservative treatment (partial or temporary resolution of symptoms) and therefore required neuroma excision. The latter occurred via medial skin incision following the course of IPSN and the area of greatest tenderness that was marked before surgery (Figure 1). After dissection of the subcutaneous soft tissues, the nerve was explored and a neuroma surrounded by scar tissue was identified (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The fibrous nodule containing the neuroma was removed. The nerve was sharply transected approximately 1-2 cm proximal to the neuroma and its proximal stump was buried to adjacent soft tissues to prevent recurrence (Figure 4). Postoperatively, no restrictions in terms of motion and weight-bearing were applied and patients were encouraged to perform knee flexion and extension exercises and gradually increase their activity level. Pregabalin was continued to a lower dose of 25 mg two or three times per day for one more month.

Active knee range of motion (ROM), visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, Knee Society Score (KSS) for pain and function were evaluated before and at least 6 mo after neuroma excision[11]. Interpretation of the VAS change scores was based on the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for adequate pain control of -3 (in a VAS scale from 0 to 10)[12,13].

Mean preoperative and follow-up values were compared with Wilcoxon signed ranks test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 and SPSS software version 24 was used.

The mean patients’ age was 71.3 ± 5.4 years old. The mean interval between TKA and neuroma excision was 10 mo (range, 6 to 14 mo) and the mean follow-up was 8 mo (range: 6 to 11 mo). Patients’ demographics are presented in Table 1.

| Patient No. | Gender | Age, yr | Height, m | Weight, kg | BMI | Interval from TKA to neuroma excision, mo | Follow-up, mo |

| 1 | F | 70 | 1.56 | 68 | 27.9 | 10 | 6 |

| 2 | F | 72 | 1.53 | 72 | 30.8 | 8 | 8 |

| 3 | F | 69 | 1.65 | 82 | 30.1 | 13 | 7 |

| 4 | M | 76 | 1.75 | 95 | 31.0 | 9 | 11 |

| 5 | F | 65 | 1.58 | 70 | 28.0 | 8 | 9 |

| 6 | F | 71 | 1.67 | 83 | 29.8 | 11 | 8 |

| 7 | F | 74 | 1.53 | 51 | 21.8 | 9 | 7 |

| 8 | F | 70 | 1.55 | 69 | 28.7 | 6 | 9 |

| 9 | F | 57 | 1.68 | 81 | 28.7 | 11 | 6 |

| 10 | M | 72 | 1.71 | 85 | 29.1 | 11 | 7 |

| 11 | F | 70 | 1.53 | 73 | 31.2 | 6 | 8 |

| 12 | F | 79 | 1.57 | 65 | 26.4 | 10 | 10 |

| 13 | F | 72 | 1.54 | 50 | 21.1 | 13 | 8 |

| 14 | F | 79 | 1.54 | 79 | 33.3 | 10 | 6 |

| 15 | F | 74 | 1.52 | 76 | 32.9 | 14 | 10 |

| mean ± SD | 71.3 ± 5.4 | 1.59 ± 0.08 | 73.3 ± 12.1 | 28.7 ± 3.5 | 10 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | |

All patients experienced almost immediate and complete pain relief and resolution of allodynia and hyperesthesia after surgery (Table 2). Mean pain relief in terms of VAS exceeded the MCID for adequate pain control (mean difference -7.8 ± 1.9, P = 0.001). Only two patients reported some residual numbness that gradually resolved during the time but didn’t cause any functional deficit.

The KSS pain and function scores were significantly improved from 49.3 ± 5.9 and 62.7 ± 12.8 before surgery to 91.8 ± 4.2 and 75.3 ± 11.3 after surgery, respectively (P = 0.001 and P = 0.015). Active knee ROM was also increased postoperatively from 96 ± 4 to 105 ± 6 degrees (P = 0.001) (Table 2).

There were no complications and no further operations required.

Iatrogenic injury of IPSN is a rare cause of postoperative pain and stiffness after TKA. The diagnosis is one of the exclusion as no specific clinical and laboratory findings can accurately diagnose the condition. Periprosthetic joint infection, malalignment, and ligamentous instability should be ruled out before the suspicion of neuroma development is taken into consideration[1]. The presence of positive Tinel’s sign along the course of the nerve and the marked improvement of the symptoms of more than 50% after diagnostic injection can confirm to a great extent the neurogenic source of pain and disability. So far, very few studies with a small number of patients and case reports have described the impact of the development of ISN on knee function after TKA and the results of conservative or surgical treatment.

Conservative management is usually the first approach utilized, including local injection of analgesics, corticosteroids, and physical therapy[14]. However, the published results are quite conflicting regarding their efficacy in alleviating pain and improving knee function. Clendenen et al[7] found that local treatment with hydrodissection of the IPSN from the adjacent interfascial planes followed by corticosteroid injection was effective in reducing persistent medial knee pain after TKA in nine out of 16 patients (VAS score of 0 or 1) with one (eight patients) or two (one patient) procedures. Three patients reported less pain improvement to VAS levels of 3 to 4. Of the remaining four patients, two did not have improvement with VAS scores of 8, and two underwent subsequent radiofrequency ablation of the IPSN with resolution of pain in one patient. Similarly, Shi et al[14] found that after ultrasound-guided local treatment by hydrodissection and corticosteroid injection of ISN, the median numeric VAS pain score was improved from 9 (range, 5 to 10) to 5 (range, 0 to 10) at both one-month and midterm follow-up (P < 0.001). The authors reported that females and a previous TKA revision were associated with less pain relief and poor results. On the other hand, Worth et al[15] reported no significant resolution of pain after local injection of the saphenous nerve in 14 patients with prior knee surgery.

In case of failed conservative treatment, surgical intervention with neurolysis, neurectomy, and selective knee denervation are utilized. The proximal nerve stump is cauterized and buried deeply in the adjacent tissues to prevent recurrence[9]. Nahabedian et al[16] excised 62 nerves in 25 patients including the IPSN in 24 cases. Complete pain relief was obtained in 11 patients (44%), partial pain relief in 10 patients (40%), and no pain relief in 4 patients (16%). The overall patient satisfaction rate was 84% (21 out of 25 patients) and none reported a worse outcome after surgery. Shi et al[1] performed selective denervation in 50 patients suffering from neuroma pain after TKA. The procedure was applied not only to IPSN but also to the other sensory nerves around the knee according to symptoms and Tinel’s sign location. Thirty-two patients (64%) rated their outcome as excellent, 10 (20%) as good, 3 (6%) as fair, and 2 (4%) reported no change. The mean VAS pain score was improved from 9.4 ± 0.8 preoperatively to 1.1 ± 1.6 postoperatively (P < 0.001). The mean Knee Society Scores was also increased from 45.5 ± 14.3 before surgery to 94.1 ± 8.6 after surgery (P < 0.0001). Three patients (6%) required a second neurectomy due to recurrent pain. In our series of 15 patients, exclusive denervation of IPSN was associated with statistically significant pain resolution (mean VAS increase -7.8 ± 1.9) and improvement of knee function (KSS pain and function scores increased from 49.3 ± 5.9 and 62.7 ± 12.8 to 91.8 ± 4.2 and 75.3 ± 11.3, respectively) and range of motion (from 96 ± 4 to 105 ± 6 degrees).

The common applied medial parapatellar approach in TKA may increase the likelihood of the development of ISN[9]. James et al[2] performed a clinical study in primary TKA patients to identify the location of the IPSN and determine whether it could be transected during a standard medial arthrotomy. They found that the nerve was, on average, between 2.58 and 3.06 cm below the inferior pole of the patella. No demographic predictors of nerve location were found, including sex, height, and BMI. Kartus et al[17] reported that the IPSN passes through the area between the apex of the patella and the tibial tubercle in 59 of 60 examined specimens and the distance from the apex of the patella to the IPSN or its uppermost branch was 30 mm. Kerver et al[18] in a cadaveric study identified that anatomic variation of topographic anatomy of IPSN is high and the nerve is at risk for iatrogenic damage in any anteromedial knee surgery, especially when longitudinal incisions are made.

The current study has certain limitations. Firstly, it represents a case series study with a relatively small sample size and no control group. It is also a single institution’s report, with scarce literature to provide an adequate comparison of data. On the other hand, it contains a homogenous group of patients that underwent only primary TKA with the same type of knee approach.

Iatrogenic injury of IPSN may cause persistent pain after TKA in an otherwise non-infected, well-fixed, and well-aligned joint. Therefore, and before TKA, patients should be warned of the risk of nerve injury and neuroma formation. After confirmation of the diagnosis with local anesthetic infiltration of the painful site, neuroma excision provides excellent pain relief and can improve the knee function and range of motion.

Development of infrapatellar saphenous neuroma (ISN) is a well-recognized source of knee pain after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

So far, very few studies have addressed the issue of the development of painful ISN after TKA, and no clear evidence regarding its importance on functional outcome and patient satisfaction exists.

The current clinical study aims to evaluate the results of surgical treatment of ISN after primary TKA, the level of pain relief, and the improvement of knee motion and function.

This study is a clinical series of 15 patients (13 women, 2 men) with persistent pain for more than six months after primary TKA due to osteoarthritis, who underwent surgical excision of ISN. Active knee range of motion (ROM), visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, Knee Society Score (KSS) for pain and function were evaluated before and at least 6 mo after neuroma excision, with a mean follow-up of 8 mo (range: 6 to 11 mo).

The mean patients’ age was 71.3 ± 5.4 years old. The mean interval between TKA and neuroma excision was 10 mo (range, 6 to 14 mo). All patients experienced almost immediate and complete pain relief and resolution of allodynia and hyperesthesia after surgery. Mean pain relief in terms of VAS exceeded the MCID for adequate pain control (mean difference -7.8 ± 1.9, P = 0.001). Only two patients reported some residual numbness that gradually resolved during the time but didn’t cause any functional deficit. The KSS pain and function scores were significantly improved from 49.3 ± 5.9 and 62.7 ± 12.8 before surgery to 91.8 ± 4.2 and 75.3 ± 11.3 after surgery, respectively (P = 0.001 and P = 0.015). Active knee ROM was also increased postoperatively from 96 ± 4 to 105 ± 6 degrees (P = 0.001). There were no complications and no further operations required

Iatrogenic injury of IPSN may cause persistent pain after TKA in an otherwise non-infected, well-fixed, and well-aligned prosthetic joint. Neuroma excision can provide excellent pain relief and improve the knee function and range of motion.

Further clinical studies are required to identify the predisposing factors for development of traumatic ISN during TKA as well as the optimal treatment approach of postoperative neurogenic pain around the knee joint area.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fouasson-Chailloux A S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Shi SM, Meister DW, Graner KC, Ninomiya JT. Selective Denervation for Persistent Knee Pain After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Report of 50 Cases. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:968-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | James NF, Kumar AR, Wilke BK, Shi GG. Incidence of Encountering the Infrapatellar Nerve Branch of the Saphenous Nerve During a Midline Approach for Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2019;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Trescot AM, Brown MN, Karl HW. Infrapatellar saphenous neuralgia - diagnosis and treatment. Pain Physician. 2013;16:E315-E324. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Xiang Y, Li Z, Yu P, Zheng Z, Feng B, Weng X. Neuroma of the Infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve following Total knee Arthroplasty: a case report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ilfeld BM, Preciado J, Trescot AM. Novel cryoneurolysis device for the treatment of sensory and motor peripheral nerves. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2016;13:713-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tennent TD, Birch NC, Holmes MJ, Birch R, Goddard NJ. Knee pain and the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:573-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Clendenen S, Greengrass R, Whalen J, O'Connor MI. Infrapatellar saphenous neuralgia after TKA can be improved with ultrasound-guided local treatments. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:119-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Laffosse JM, Potapov A, Malo M, Lavigne M, Vendittoli PA. Hypesthesia after anterolateral vs midline skin incision in TKA: a randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:3154-3163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kachar SM, Williams KM, Finn HA. Neuroma of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve a cause of reversible knee stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:927-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parvizi J, Tan TL, Goswami K, Higuera C, Della Valle C, Chen AF, Shohat N. The 2018 Definition of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Infection: An Evidence-Based and Validated Criteria. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1309-1314.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 885] [Cited by in RCA: 1403] [Article Influence: 200.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;13-14. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lee JS, Hobden E, Stiell IG, Wells GA. Clinically important change in the visual analog scale after adequate pain control. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1128-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Higgins J, Deeks J. Chapter 9: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, UK: John Willey & Sons; 2008. page 243-296. |

| 14. | Shi GG, Schultz DS Jr, Whalen J, Clendenen S, Wilke B. Midterm Outcomes of Ultrasound-guided Local Treatment for Infrapatellar Saphenous Neuroma Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Cureus. 2020;12:e6565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Worth RM, Kettelkamp DB, Defalque RJ, Duane KU. Saphenous nerve entrapment. A cause of medial knee pain. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:80-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nahabedian MY, Johnson CA. Operative management of neuromatous knee pain: patient selection and outcome. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:15-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kartus J, Ejerhed L, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J. The localization of the infrapatellar nerves in the anterior knee region with special emphasis on central third patellar tendon harvest: a dissection study on cadaver and amputated specimens. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:577-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kerver AL, Leliveld MS, den Hartog D, Verhofstad MH, Kleinrensink GJ. The surgical anatomy of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve in relation to incisions for anteromedial knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:2119-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |