Published online Nov 18, 2021. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i11.938

Peer-review started: June 8, 2021

First decision: July 28, 2021

Revised: August 6, 2021

Accepted: September 15, 2021

Article in press: September 15, 2021

Published online: November 18, 2021

Processing time: 160 Days and 4.7 Hours

Various etiologies contribute to pathological fractures, including bone infections. Recently, non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium-related bone infections among patients with anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody-induced adult-onset immunodeficiency has raised concerns in Southeast Asia, with the common presentations including osteomyelitis. However, it also rarely manifests as traumatic fractures, as reported in this case.

A diabetic female fractured her humerus after a traumatic accident and received fixation surgery. Abnormal necrotic bone tissue and abscess formation were noted, and she was diagnosed with a pathological fracture due to non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium infection. Multiple bone involvement was also revealed in a bone scan. Anti-interferon-gamma autoantibodies were then checked due to an unexplained immunocompromised status and found to be positive. Her humerus fracture and multiple bone infections healed after steroid and anti-non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium medication treatment following fixation surgery.

Comprehensive preoperative evaluations may help identify pathological fractures and guide the treatment course.

Core Tip: Identifying neutralizing anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody-related non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium bone infections requires careful history taking and physical examinations. While a biopsy of the bone lesion is the gold standard for diagnosis, it is advisable to check co-existing lymphadenopathy, dermatoses, and lung and blood-stream infections, as they provide easily accessible specimens for culturing and cytopathology. Serum tests of immune profiles are also important for atypical or opportunistic infections. These pre-operative evaluations may guide the choice of surgical modality, medical treatment that accompanies surgery, and decide the prognosis of healing.

- Citation: Yang CH, Kuo FC, Lee CH. Pathological humerus fracture due to anti-interferon-gamma autoantibodies: A case report. World J Orthop 2021; 12(11): 938-944

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v12/i11/938.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i11.938

Pathological fractures can be secondary to conditions ranging from metabolic diseases to tumors, infections, or neuromuscular pathologies. Unfortunately, those due to infections can be mistaken for malignant tumors[1]. Distinguishing between hematogenous osteomyelitis and bone tumors is difficult when there are no obvious clinical clues, and radiographic changes in osteomyelitis are often mistaken for tumors[2]. Herein, we present a diabetic female diagnosed with a humerus fracture after a traumatic injury. The purpose of this case report is to remind orthopedic surgeons not to overlook the possible diagnosis of a pathological fracture secondary to non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium (NTM) bone infections due to anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody (AIGA)-induced adult-onset immunodeficiency, a disease with increasing incidence in Southeast Asia in the recent decade, that can present as a traumatic fracture.

In this case, the AIGA presence itself was proposed to have occurred due to genetic susceptibility of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes[3] and through molecular mimicry, such as an epitope of interferon-gamma that mimics Aspergillus antigen (Noc-2 protein)[4], a known cause of this type of autoimmunity. The accumulation of environmental Aspergillus antigen exposure might gradually trigger an immune response, producing auto-antibody against human interferon-gamma and thereby resulting in opportunistic infections. Among these infections, NTM has prompted greater concern due to its being an important component of opportunistic infections. In this case report, we aimed to elucidate the NTM bone infection due to AIGA-induced adult-onset immunodeficiency that caused pathologic fracture which was overlooked as traumatic fracture.

A 69-year-old diabetic female presented with right upper arm pain with deformity.

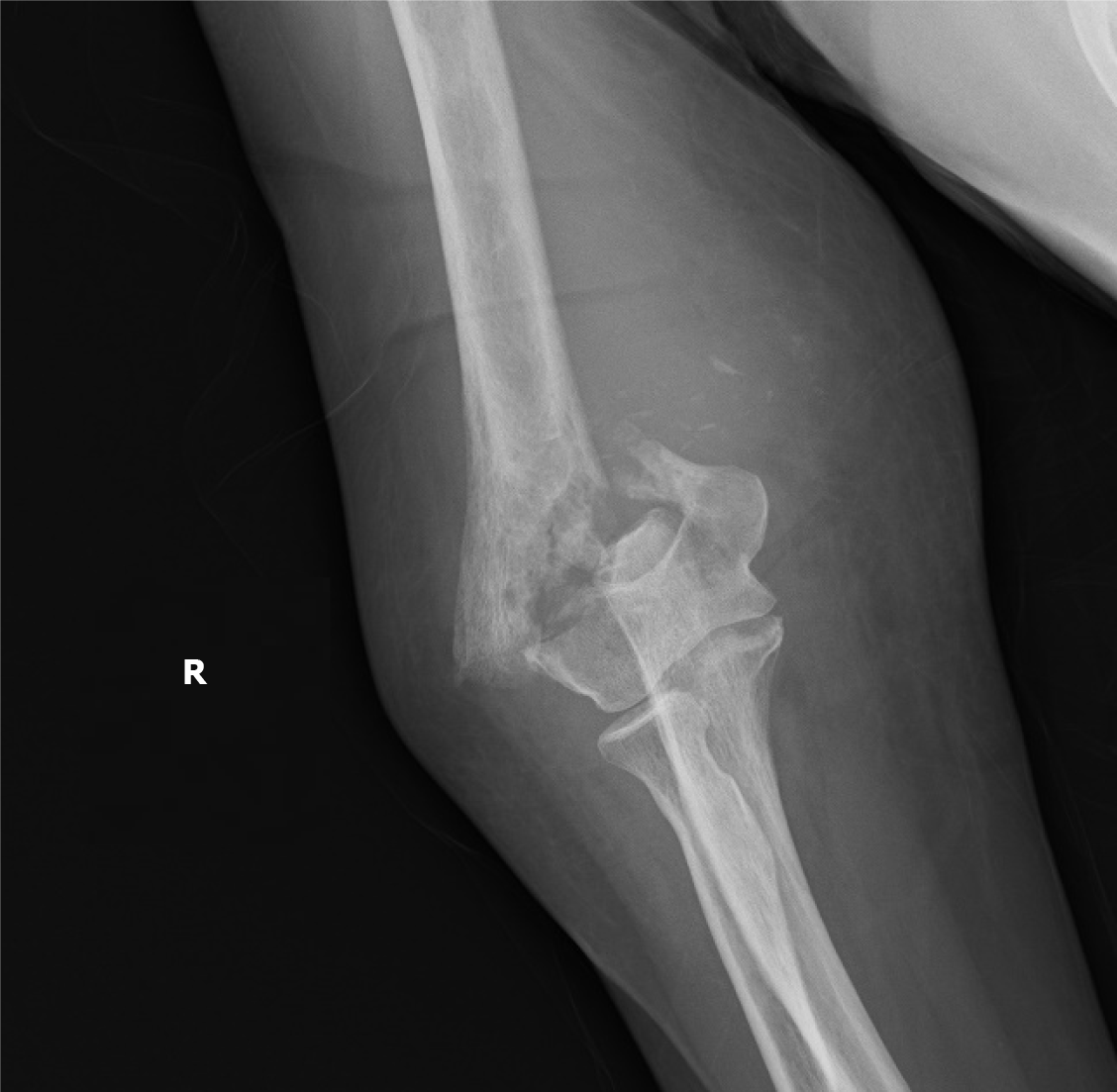

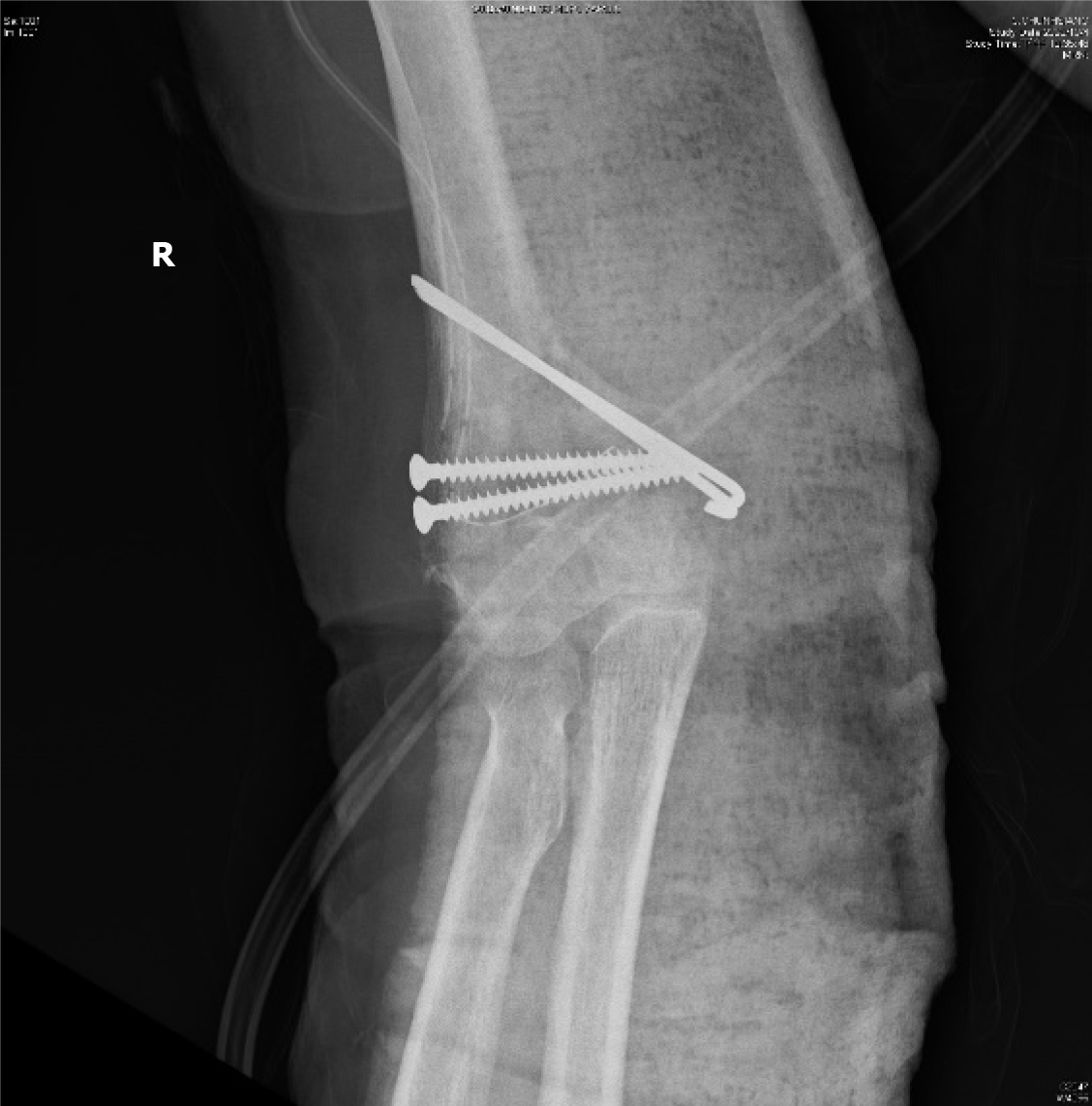

The patient fell from her bed during the night and fractured her right humerus (Figure 1). She was then admitted for surgical fixation (Figure 2).

The patient had diabetes mellitus type 2 with a hemoglobin A1c level of 5.8, under treatment with glipizide 1# twice daily.

The patient had no hereditary malignancies or bone diseases and denied smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol.

A painful right elbow deformity, tenderness, and limited range of motion were noted. After the fracture fixation surgery, the patient’s family found a non-healing wound with abscess formation that had developed on her chest wall near the sternum. Bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy was also noted.

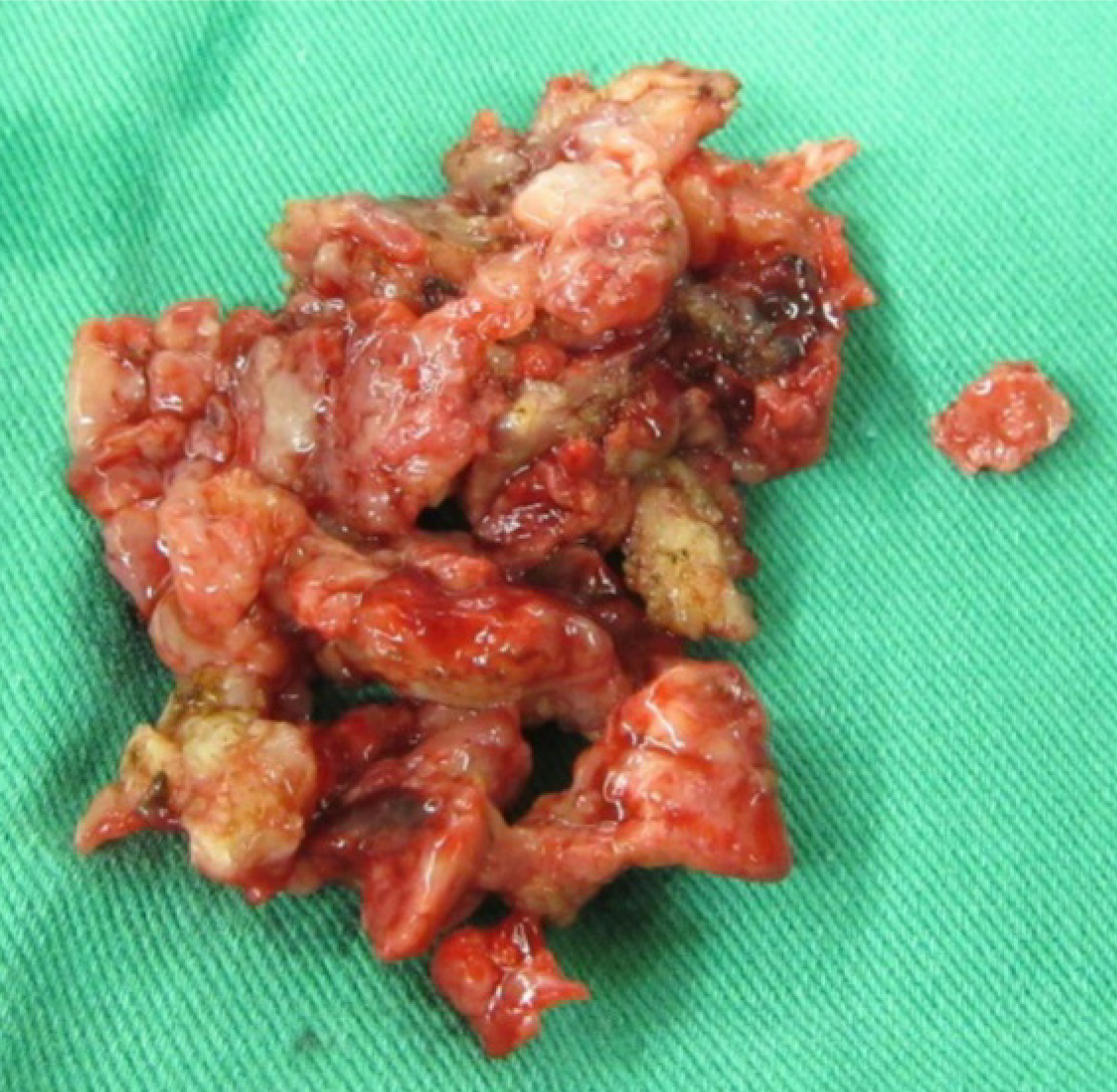

Unlike an acute traumatic fracture, necrotic bone tissues were noted and sequestrated intraoperatively (Figure 3). The specimen consisted of more than 10 tissue fragments, measuring up to 1.9 cm × 1.2 cm × 0.5 cm. Representative sections were taken, showing bone and fibrosynovial tissue with necrosis, granulation tissue proliferation, and marked acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. A malignancy-related pathological fracture was suspected. Sternum abscess excision and pathology revealed skin tissue with subcutaneous necrosis, fat necrosis, and dense acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, without malignancy. Mycobacterium intracellulare was cultured via pus drainage. A lymph node excision biopsy was also performed, and the pathology revealed necrotizing granulation without malignancy. An immunosuppression status was suspected due to opportunistic infections. The patient had a normal lymphocyte subpopulation and tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Neutralizing (n)AIGAs were then considered. Serologically, high titers of AIGAs (1:106) were observed.

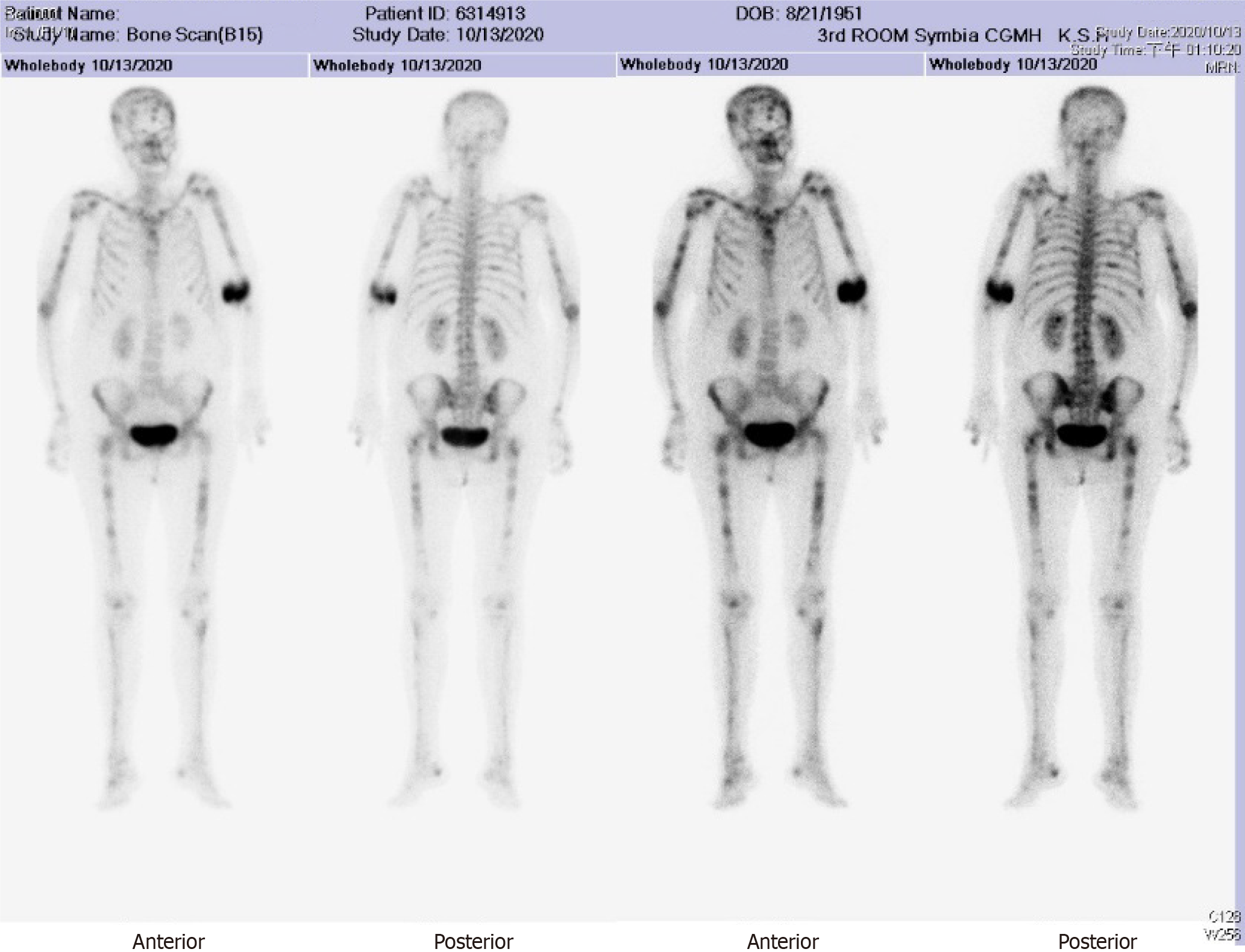

Plain X-ray revealed a displaced supracondylar humerus fracture of the right elbow (Figure 1). A bone scan revealed increased uptake over the skull, spine, bilateral pelvis, femur, tibia, tarsal bones, scapulae, clavicles, humeri, right forearm, sternum, and rib cage, indicating probable multiple metastases (Figure 4).

Disseminated (d)NTM infection with lymphadenopathy and multiple bone lesions causing a right humerus pathological fracture and sternum abscess formation. nAIGA-induced adult-onset immunodeficiency.

The patient was treated with open reduction and internal fixation with cancellous screws and Kirschner wires (Figure 2) for the fracture. She was administered cortisone (4 mg) 1# orally twice daily for the autoantibodies, and rifampicin, ethambutol, and clarithromycin for the dNTM infection.

After a 1-mo treatment course, a physical examination showed that the humerus fracture had healed, and the sternum infection had also gradually healed along with the other infected bones. The patient will continue to receive regular treatment during future outpatient visits.

Etiologies of pathological fractures include bone infection, malignancy, endo

Various pathogens can cause bone infections, among which NTM is a rare but noteworthy cause, as is the present case. The incidence of NTM infection has increased in recent years, likely due to advances in diagnostic technology. In addition, the rate of dNTM infection in HIV carriers has fallen from 16% in 1996 to less than 1% today due to the introduction of effective anti-viral therapy for HIV and macrolide prophylaxis[6]. The cause of other non-HIV-related immunocompromising conditions in patients with dNTM infection is thus of concern, most notably nAIGA-induced adult-onset immunodeficiency. nAIGAs are detected in 88% of Asian adults with multiple opportunistic infections without HIV infection[7]. nAIGA-induced adult-onset immunodeficiency is an autoimmune disease associated with HLA-DQB1/DRB1 and depleted interferon-gamma/interleukin 12-mediated cellular immunity, with increased susceptibility to opportunistic NTM infections frequently involving the lungs, lymphadenopathy, cutaneous, and the musculoskeletal system, as in our case.

However, an acute and accurate diagnosis of musculoskeletal NTM infection is often difficult because of the indolent clinical course and difficulty in isolating pathogens[8]. A recent prospective case-control study in Taiwan[9] reported an average 1.6 year delay in the diagnosis of nAIGA-related dNTM due to protean manifestations mimicking other systemic illnesses, including mycobacterial tuberculosis, malignancy, and connective tissue diseases. Multivariate analysis revealed that slow-growing NTM species (i.e., Mycobacterium intracellulare) in nAIGA cases were associated with multiple bone involvement. These findings are comparable with our case. Osteomyelitis and bone marrow infections have also been associated with bone manifestations of dNTM in nAIGA patients in previous studies. In contrast, a pathological fracture was the initial presentation in our case. It is important to note that NTM osteomyelitis often arises from previous trauma or surgical sites among patients with weak immunity and dNTM infection, and osteomyelitis is also considered to be a presentation of immune reconstruction inflammatory syndrome[8].

Our case also impressed as a traumatic fracture initially according to the patient’s injury history but was later found to have an NTM bone infection-related pathological fracture mimicking metastatic malignancy. Interestingly, in addition to granulomatous disease-induced bone loss, nAIGA can also induce an increase in osteoclast formation and bone resorption via RANKL-induced activation of the NF-kB pathway, thereby worsening NTM infection-induced bone erosion[10]. We therefore suggest that nAIGA should be considered an independent risk factor for pathological fractures.

As relatively few reports on NTM-related pathological fractures are available, our case provides valuable insight into the comparison with malignancy-related pathological fractures. Risk factors associated with the prognosis of malignancy-related pathological fractures include primary cancer type, spinal involvement, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status, and whether the patient received chemotherapy/radiotherapy. The median survival is 4.1 mo. Surgical treatment for pathological fractures includes intramedullary nails, plate fixation, and arthroplasty.

A retrospective cohort study[11] found that fracture site, method of fixation, and use of cement augmentation did not have a statistically significant impact on survival post-fracture. Another case-control study[12] found that cement fixation, in addition to open reduction and internal fixation, could result in immediate stabilization and thus better pain control without impairing the range of motion. In our case, the orthopedic doctor discussed the risks and benefits of different treatment methods with the patient. She chose to receive open reduction and internal fixation and subsequently underwent cancellous screw with Kirschner wire fixation for the humerus fracture. However, if we had noticed her sternum abscess lesion prior to surgery, we may have chosen a more intense fixation method under the suspicion/evidence of a pathological fracture. A more complete physical examination with preoperative planning may be helpful in such cases. In addition, further studies are warranted to investigate the preferred method of surgery, prognostic factors, and median survival of bone infection (such as NTM)-related fractures.

As T lymphocyte dysfunction predisposes patients to dNTM infection, we advise screening for nAIGA in HIV-negative Asian patients with NTM bone infection-related pathological fractures, especially when combined with other unexplained opportunistic infection history such as zoster, salmonellosis, histoplasmosis, and aspergillosis[7]. The histopathologic features of NTM bone infection show a spectrum of inflammatory changes, including granulomatous lesions with or without caseation[13]. With regards to treatment, it is necessary to differentiate nAIGA-related dNTM bone disease from Pott’s disease, monoclonal gammopathies, and other malignancies sharing similar features. Efficacy and drug resistance should be carefully evaluated for long-term anti-NTM treatment, and it is important that this is accompanied by surgical debridement and fracture treatment[8].

The immunosuppressants used for nAIGA include corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, while rituximab has also been reported to be effective[7,14]. nAIGA titers have been reported to decrease over time even without immunosuppressive treatment. However, rates of chronic opportunistic infections and death remain high[10]. Screening for nAIGA in dNTM-related pathological fractures is recommended to allow for appropriate treatment, thereby decreasing morbidity. A careful preoperative survey is important in potential pathological fracture cases.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akbulut S, Feng J, Wang XJ S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Canavese F, Samba A, Rousset M. Pathological fractures in children: Diagnosis and treatment options. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:S149-S159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shimose S, Sugita T, Kubo T, Matsuo T, Nobuto H, Ochi M. Differential diagnosis between osteomyelitis and bone tumors. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ku CL, Lin CH, Chang SW, Chu CC, Chan JF, Kong XF, Lee CH, Rosen EA, Ding JY, Lee WI, Bustamante J, Witte T, Shih HP, Kuo CY, Chetchotisakd P, Kiertiburanakul S, Suputtamongkol Y, Yuen KY, Casanova JL, Holland SM, Doffinger R, Browne SK, Chi CY. Anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies are strongly associated with HLA-DR*15:02/16:02 and HLA-DQ*05:01/05:02 across Southeast Asia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:945-8.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin CH, Chi CY, Shih HP, Ding JY, Lo CC, Wang SY, Kuo CY, Yeh CF, Tu KH, Liu SH, Chen HK, Ho CH, Ho MW, Lee CH, Lai HC, Ku CL. Identification of a major epitope by anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies in patients with mycobacterial disease. Nat Med. 2016;22:994-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mukhopadhyay S, Mukhopadhyay J, Sengupta S, Ghosh B. Approach to pathological fracture physician’s perspective. Austin Intern Med. 2016;1:1014. |

| 6. | Kadzielski J, Smith M, Baran J, Gandhi R, Raskin K. Nontuberculous mycobacterial osteomyelitis: a case report of Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex tibial osteomyelitis in the setting of HIV/AIDS. Orthop J Harvard Med. 2009;11:108-111. |

| 7. | Li WS, Huang WC, Ku CL, Lee CH. Osteolytic lesions resulting from opportunistic infections. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2017;33:365-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park JW, Kim YS, Yoon JO, Kim JS, Chang JS, Kim JM, Chun JM, Jeon IH. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection of the musculoskeletal system: pattern of infection and efficacy of combined surgical/antimicrobial treatment. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1561-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu UI, Wang JT, Sheng WH, Sun HY, Cheng A, Hsu LY, Chang SC, Chen YC. Incorrect diagnoses in patients with neutralizing anti-interferon-gamma-autoantibodies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1684.e1-1684.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Deng J, Sun D, Luo F, Zhang Q, Chen F, Xu J, Zhang Z. Anti-IFN-γ Antibody Promotes Osteoclastogenesis in Human Bone Marrow Monocyte-Derived Macrophages Co-Cultured with Tuberculosis-Activated Th1 Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;49:1512-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Salim X, D'Alessandro P, Little J, Mudhar K, Murray K, Carey Smith R, Yates P. A novel scoring system to guide prognosis in patients with pathological fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13:228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Laitinen M, Nieminen J, Pakarinen TK. Treatment of pathological humerus shaft fractures with intramedullary nails with or without cement fixation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:503-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Marchevsky AM, Damsker B, Green S, Tepper S. The clinicopathological spectrum of non-tuberculous mycobacterial osteoarticular infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:925-929. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Browne SK, Zaman R, Sampaio EP, Jutivorakool K, Rosen LB, Ding L, Pancholi MJ, Yang LM, Priel DL, Uzel G, Freeman AF, Hayes CE, Baxter R, Cohen SH, Holland SM. Anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapy for anti-IFN-γ autoantibody-associated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Blood. 2012;119:3933-3939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |