Published online Sep 18, 2020. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i9.380

Peer-review started: May 7, 2020

First decision: May 15, 2020

Revised: May 28, 2020

Accepted: August 15, 2020

Article in press: August 15, 2020

Published online: September 18, 2020

Processing time: 130 Days and 5.7 Hours

Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIMN) is relatively contraindicated for pediatric length unstable femoral fractures.

To evaluate FIMN treatment outcomes for pediatric diaphyseal length unstable femoral fractures in patients aged 5 to 13 years.

This retrospective study includes pediatric patients (age range 5-13 years) who received operative treatment for a diaphyseal femoral fracture at a single institution between 2013 and 2019. Length unstable femur fractures treated with FIMN were compared to treatment with other fixation methods [locked intramedullary nailing (IMN), submuscular plating (SMP), and external fixation] and to length stable fractures treated with FIMN. Exclusion criteria included patients who had an underlying predisposition for fractures (e.g., pathologic fractures or osteogenesis imperfecta), polytrauma necessitating intensive care unit care and/or extensive management of other injuries, incomplete records, or no follow-up visits. Patients who had a length stable femoral fracture treated with modalities other than FIMN were excluded as well.

Ninety-five fractures from ninety-two patients were included in the study and consists of three groups. These three groups are length unstable fractures treated with FIMN (n = 21), length stable fractures treated with FIMN (n = 45), and length unstable fractures treated with either locked IMN, SMP, or external fixator (n = 29). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Patient characteristic differences that were statistically significant between the groups, length unstable with FIMN and length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, or external fixator, were average age (7.4 years vs 9.3 years, respectively), estimated blood loss (29.2 mL vs 98 mL, respectively) and body mass (27.8 kg vs 35.1 kg, respectively). All other patient characteristic differences were statistically insignificant. Regarding complications, length unstable with FIMN had 9 total complications while length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, or external fixator had 10. Grouping these complications into minor or major, length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, or external fixator had 6 major complication while length unstable with FIMN had 0 major complications. This difference in major complications was statistically significant. Lastly, when comparing patient characteristics between the groups, length unstable with FIMN and length stable with FIMN, all characteristics were statistically similar except time to weight bearing (39 d vs 29 d respectively). When analyzing complication differences between these two groups (9 total complications, 0 major vs 20 total complications, 4 major), the complication rates were considered statistically similar.

FIMN is effective for length unstable fractures, having a low rate of complications. FIMN is a suitable option for length stable and length unstable femur fractures alike.

Core Tip: There is debate between orthopaedic surgeons regarding proper treatment for length unstable femoral fractures in patients between the ages of 5 and 11. In our manuscript we present results demonstrating that flexible intramedullary nailing in this subset of patients is an effective form of treatment and compares well to other forms of treatment for this subset of patients. Our results also compare favorably to those from recently published literature pieces on this same subject.

- Citation: Mussell EA, Jardaly A, Gilbert SR. Length unstable femoral fractures: A misnomer? World J Orthop 2020; 11(9): 380-390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v11/i9/380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v11.i9.380

Diaphyseal femoral fractures account for roughly 1.6% of fractures in pediatric patients 5-18 years of age with an incidence of 19 per 100000 children[1,2] and are more common in males[3]. These fractures place a substantial burden on the patient and their family due to hospitalizations, complex treatment options, and lengthy recovery times[2,4]. Fracture pattern, length stability, patient weight/age, geographic location, and surgeon preference all play a role in the choice of treatment[1]. Surgical intervention is nearly always recommended for pediatric femoral fracture patients above the age of 5[5].

Length unstable fractures have been defined as spiral/long oblique or comminuted, with a fracture line length ≥ twice the diameter of the femoral shaft at the level of the fracture[5-11]. This fracture is often associated with > 2 cm of shortening[5,12]. The length unstable diaphyseal femoral fracture is problematic in children ages 5–11 due to the long recovery time, skeletal immaturity, heightened risk of post-operative complications, and a lack of consensus as to the proper fixation modality[5,6,13]. Options include external fixation (Ex fix), submuscular plating (SMP), open/compression plating, flexible intramedullary nailing (FIMN) (titanium vs stainless steel) (locked vs non-locked), rigid intramedullary nailing, ex fix in combination with elastic nailing, semi-rigid pediatric locking nail, and others[14-16]. FIMN of the pediatric femur, which is synonymous with both titanium elastic nailing and elastic stable intramedullary nailing, provides immediate-to-early stability to the involved bone segment, permitting early mobilization and allows for return to normal activities with a relatively low complication rate[17]. Although FIMN is an effective procedure for length stable diaphyseal pediatric femoral fractures, there is concern regarding its use for length unstable fractures[8,9,14,18-21]. Potential complications with FIMN treatment for length unstable fractures include suboptimal stability leading to angulation, shortening, rotation[8,22-24], and nail protrusion resulting in symptomatic hardware with skin irritation being the primary patient complaint[6,16,25].

Despite the above concerns, FIMN is still often used for length unstable femur fractures. We hypothesized that FIMN is a viable option for length unstable femur fractures with a rate of complications that does not differ unfavorably from other treatment options. We performed a retrospective chart review at a single institution to compare FIMN with other treatment options for length unstable femur fractures with a primary outcome of complications. Also, because the treatment group, length unstable other than FIMN, was slightly older and heavier, we utilized a second comparison group, length stable fractures treated with FIMN.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Billing databases at a single institution were used to identify patients (age range 5–13) who had received surgical management of a diaphyseal femoral fracture from 2013–2019. Charts and radiographs were reviewed. Recorded data included patient characteristics (sex, age, weight, fracture type, blood loss from surgery, follow-up duration and time to weight bearing) and complications (rotational deformity, shortening, arthrofibrosis, symptomatic hardware, treatment change, wound complications, and decreased range of motion). Complications were stratified into minor and major in accordance with previous studies[26]. Minor complications constitute pain at the nail insertion site (i.e., symptomatic hardware) and temporary complications that are self-resolving or that are completely resolved without surgery (e.g. superficial surgical site infection and superficial wound complications). Major complications are those persisting at final follow-up or those requiring additional procedures and include instrument failure requiring revision, rotational deformities requiring surgical correction, and arthrofibrosis requiring knee manipulation under anesthesia. The only exception to an additional procedure considered as a minor complication is hardware removal due to symptoms. Patients who had an elective hardware removal in the absence of symptoms were not included as complications. Rotational deformity and leg-length discrepancy were assessed clinically by the treating orthopaedist. If a clinical concern of either deformity was raised, then long-leg X-rays with the contralateral leg were obtained. Shortening was measured on lateral X-rays and was defined as shortening greater than 14 mm, which is the upper acceptable limit in the literature[27].

Inclusion criteria is a femur fracture in a patient aged 5-13 years. One hundred and sixty-three such patients were identified. Cases were excluded if they had an underlying predisposition for fractures (e.g., pathologic fractures or osteogenesis imperfecta) (9 patients), polytrauma necessitating intensive care unit care and/or extensive management of other injuries [may skew data on variables including estimated blood loss (EBL), operative time, and time to weight bearing due to the associated injuries] (12 patients), incomplete records (8 patients), or no follow-up visits (12 patients). Thirty patients were also excluded as they had a length stable fracture treated with modalities other than FIMN. Ninety-two patients with 95 fractures were included. They constituted three groups: Length unstable femoral fractures treated with FIMN, length unstable femoral fractures treated with a modality other than FIMN (locked IMN, SMP, and external fixators), and length stable femoral fractures treated with FIMN. Primary outcomes for the study were the number and percentage of complications per each group and the secondary outcomes included the types of complications per each group (e.g. symptomatic hardware, rotational deformity, etc.) and their severity (major or minor).

A two-tailed t-test and a chi-square test were performed for continuous and categorical data, respectively. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Regarding the primary surgical treatment of interest in this study, FIMN, the procedure described in depth by Busch et al[26] is the one predominantly carried out at our institution. Also, patient follow-up was achieved in clinic at our institution from the first presentation of the involved femoral fracture(s) to the patient’s last clinic visit. Our institution also does not typically cast fractures in conjunction with FIMN, and patients included in this study were not casted after surgical correction. The treating orthopaedist considered the fracture(s) completely resolved when union was evident on x-ray and when the patient’s symptoms, specific to the prior femoral fracture(s) of concern, were resolved. All patients were given the option of additional follow-up in clinic if symptoms reemerged and/or if a physical deformity appeared.

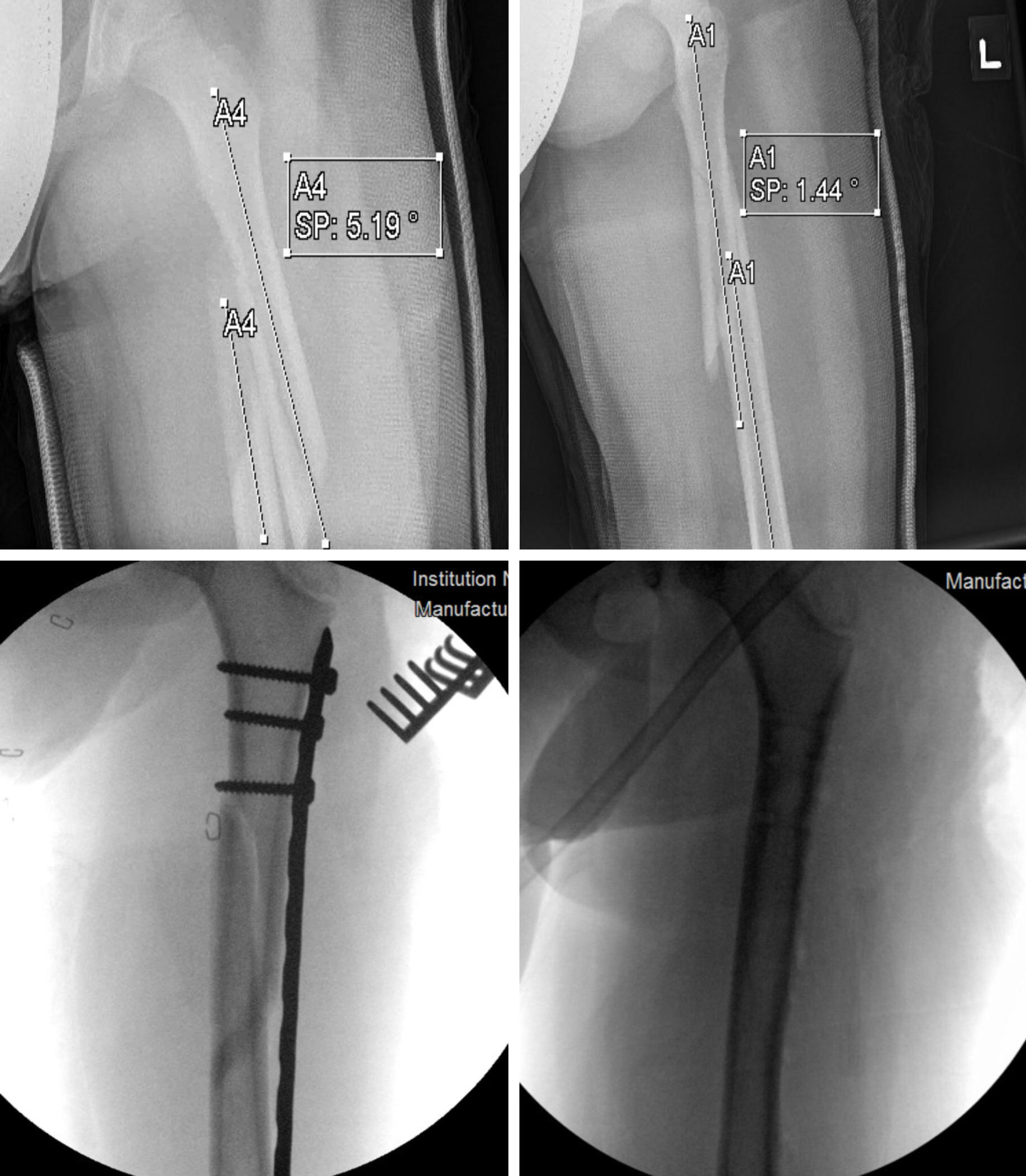

Ninety-five fractures from ninety-two patients were included in this study. There were 50 length unstable fractures (Table 1). Twenty-one were treated with titanium FIMN, and included 17 males and 4 females, with an average age of 7.4 years (range: 5.2–11.9 years) and weight of 27.8 kg (range: 10.6–56.7 kg). Sixteen fractures were long spiral or oblique, and the remaining 5 were comminuted. Patients were followed up for an average of 10.6 mo (range: 2–51.5 mo), and time from surgery to weightbearing as tolerated was 39 d (range: 23–60 d). 9 patients (42.8%) experienced a complication, with 8 being symptomatic hardware. One patient had superficial wound dehiscence. All complications, therefore, were minor, and no major complications were encountered. An example of a length unstable femur fracture treated with FIMN is included in Figure 1.

| Length unstable with FIMN (n = 21) | Length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, or external fixator (n = 29) | P value | |||||

| Patient characteristics | Average | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Sex | 0.19 | ||||||

| Male | 17 | 27 | |||||

| Female | 4 | 2 | |||||

| Age, yr | 7.41 | 5.2 | 11.9 | 9.31 | 5.8 | 12.4 | 0.004 |

| Weight, kg | 27.81 | 10.6 | 56.7 | 35.11 | 18 | 68 | 0.033 |

| Fracture type | 0.29 | ||||||

| Spiral or oblique | 16 | 18 | |||||

| Comminuted | 5 | 11 | |||||

| Blood loss, mL | 29.21 | 5 | 100 | 981 | 10 | 500 | 0.0036 |

| Follow-up duration, mo | 10.6 | 2 | 51.5 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 0.37 |

| Time to weightbearing, d | 39 | 23 | 60 | 36 | 12 | 63 | 0.45 |

| Complications | Number (%) | Number (%) | |||||

| Malunion | 0 | 1 (3.4%) | |||||

| Shortening | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Arthrofibrosis | 0 | 2 (6.9%) | |||||

| Symptomatic | 8 (38%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||||

| Hardware | 0 | 1 (3.4%) | |||||

| Changing treatment | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||||

| Wound complications | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Decreased ROM | |||||||

| Total | 9 (42.8%) | 10 (34.5%) | 0.55 | ||||

| Minor | 9 (100%) | 4 (40%) | 0.021 | ||||

| Major | 0 (0%) | 6 (60%) | 0.026 | ||||

Twenty–nine length unstable fractures were treated with a technique other than FIMN. These were older patients (9.3 years vs 7.4 years, P = 0.004) with a greater weight (35.1 kg vs 27.8 kg, P = 0.033), but both groups were similar in their sex distribution, fracture pattern, time to weightbearing, and follow-up duration (P > 0.05, Table 1). Blood loss during surgery was greater in this group as compared to FIMN (98 mL vs 29.2 mL, P = 0.0036). 10 total complications (34.5%) were encountered, with 4 being minor complications (13.8%) and 6 being major ones (20.7%). The minor complications included 3 patients with symptomatic hardware and 1 keloid formation. Major complications were pin infection or fixator disturbance requiring hardware removal (n = 3), genu valgum requiring hemiepiphysiodesis (n = 1), and arthrofibrosis requiring knee manipulation under anesthesia (n = 2). Figure 2 consists of radiographs representing the treatment of a pediatric diaphyseal femoral fracture, with a large comminution, originally treated with external fixation. Pin site infections occurred in the patient, requiring changing the treatment to a spica cast. The overall complication rate for length unstable fractures was similar regardless of the treatment employed (42.8% for FIMN vs 34.5% for other methods of fixation, P = 0.55). FIMN had less major and more minor complications compared to the other methods of fixation for length unstable femur fractures (P of 0.026 and 0.021, respectively).

We also evaluated whether FIMN was associated with more complications when used for length unstable vs length stable fractures. FIMN was used for 45 length stable femur fractures (Table 2). Both groups had similar sex distribution, age, weight, follow-up duration, and estimated operative blood loss (P > 0.05, Table 2). The length stable group was allowed to bear weight, as tolerated, 10 d sooner (P = 0.001). 20 overall complications (44.4%) were observed in this group. Sixteen were minor complications due to either symptomatic hardware (n = 15) or superficial wound dehiscence (n = 1). Major complications were bilateral fixation failure in a patient weighing 47.4 kg as well as 2 fractures with persistent arthrofibrosis. The rates of total minor and major complications were similar in fractures treated with FIMN regardless of fracture stability (P > 0.15 for each).

| Length unstable fractures (n = 21) | Length stable fractures (n = 45) | P value | |||||

| Patient characteristics | Average | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Sex | 0.24 | ||||||

| Male | 17 | 28 | |||||

| Female | 4 | 14 | |||||

| Age, yr | 7.4 | 5.2 | 11.9 | 8.5 | 4.6 | 12.8 | 0.062 |

| Weight, kg | 27.8 | 10.6 | 56.7 | 32.1 | 16 | 58.5 | 0.144 |

| Blood loss, mL | 29.2 | 5 | 100 | 33.9 | 5 | 200 | 0.57 |

| Follow-up duration, mo | 10.6 | 2 | 51.5 | 6.8 | 1 | 24 | 0.204 |

| Time to weightbearing, d | 391 | 23 | 60 | 291 | 12 | 47 | 0.001 |

| Complications | Number (%) | Number (%) | |||||

| Malunion | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Shortening | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Arthrofibrosis | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Symptomatic hardware | 8 (38%) | 15 (33.3%) | |||||

| Changing treatment | 0 | 2 (4.4%) | |||||

| Wound complications | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (2.2%) | |||||

| Decreased ROM | 0 | 2 (4.4%) | |||||

| Total | 9 (42.8%) | 20 (44.4%) | 0.805 | ||||

| Minor | 9 (100%) | 16 (80%) | > 0.15 | ||||

| Major | 0 (0%) | 4 (20%) | > 0.15 | ||||

Lastly, Figure 3 depicts the treatment of another pediatric length unstable spiral fracture, but instead of FIMN, it was treated with SMP. The patient went on to have significant keloid scars at the 2 incisions sites. With FIMN as a treatment modality, only two 2–3 cm incisions are needed, one each at the lateral and medial borders of the distal femoral metaphysis, while SMP for this patient required at least two 5-6 cm incisions total for the submuscular plate and 6 screws.

This single institution, retrospective comparative/cohort study found that length unstable, pediatric femur fractures treated with FIMN had similar complication rates to other fixation methods for length unstable fractures and to length stable fractures treated with FIMN. Thus, FIMN remains a viable option for certain length unstable femur fractures.

Multiple treatment modalities for length unstable, pediatric femoral fractures remain. External fixation is an option, particularly when extensive soft tissue damage and or contamination is present, but is associated with complications such as refracture, delayed union, malunion, unappealing scars, and pin tract infections[28-33]. Rigid intramedullary nailing may not be feasible in some cases due to implant size relative to the pediatric canal and is relatively contraindicated for pediatric patients due to the risk of avascular necrosis of the femoral head[34-37]. SMP is a modern, viable treatment option for length unstable diaphyseal femur fractures[1,7,9,29,31,32,38-40]. Open/compression plating offers a rigid construct with good operative exposure but involves a large incision, soft tissue disruption, increased blood loss, and leads to incomplete primary bone healing with limited callus and therefore is contraindicated in exchange for non-invasive treatments[12,41].

FIMN fracture fixation is minimally invasive with no preselection needed for proper implant length and power instruments are not needed. FIMN treatment also has lower EBL, shorter operative times comparatively, and a low risk of avascular necrosis compared to other treatment options[21,42]. The use of FIMN for pediatric femoral fractures has its limits, however. Reports on its success in length unstable fractures are variable. Sink et al[8] reported on the outcomes of 39 pediatric femur fractures treated with FIMN, 24 of which were length stable and 15 were length unstable. For the length stable fractures, 12 had complications (12/24 or 50%), 2 of which needed a second surgery for correction. As for the length unstable group, 12 also had complications (12/15 or 80%), 6 of which needed a second surgery for correction. While their complication rate between unstable vs stable fractures treated with FIMN was not statistically significant, the difference in the number of patients requiring a second surgery in each group was statistically significant. Allen et al[21] did a retrospective study on all pediatric femur fracture patients within their institution from 2004–2014 and found that patients had similar outcomes between the SMP and FIMN groups regardless of length stability. Further, they favored FIMN compared to plating due to decreased operative time, EBL, and cost. Both procedures had equivalent pain measures. Lastly, Siddiqui et al[43] did a retrospective study of femur fracture patients, age 1–11 (mean age 5 ± 2). Fifty-eight femoral shaft fractures were included; 32/58 fractures were classified as length unstable and 26/58 fractures were stable. They found no difference in the complication rate between length unstable and length stable fractures treated with FIMN.

The results from this study regarding the use of FIMN for length unstable femoral fractures compares well to the use of other treatment modalities for length unstable femoral fractures as well as to length stable, transverse fractures treated with FIMN. The total complication rates of FIMN use for length unstable femur fractures versus other treatments was similar. However, stratifying the complications into minor and major yields a difference. FIMN did not have any major complications, while the other treatment modalities had clinically significant complications like rotational deformity and valgus (P = 0.026). When comparing the complication rate of unstable fractures treated with FIMN vs stable transverse fractures treated with FIMN, the results were similar. When considering these results and the other factors for supporting FIMN use over other treatment methods as reported by Allen et al[21], FIMN is a favorable treatment option for pediatric femur fracture patients within the ideal 5–11 age range, regardless of length stability.

This study has limitations. First, due to this study’s retrospective nature, the value of data we collected was dependent on the adequacy of chart documentation. There was no standardized system for treatment selection at our institution and therefore treatment was largely based on surgeon preference. There were cases where surgeons specifically documented a decision against the use of FIMN due to a fracture’s degree of length instability and/or extent of other concomitant injuries, indicating some selection bias. Long-term follow up and patient-reported outcome measures were not performed for this study and are needed to further support these findings.

This study supports the concept that FIMN can still be used in many length unstable pediatric femur fractures treated with FIMN. Further work is necessary to define the appropriate parameters and/or algorithm(s) necessary for deciding if a pediatric length unstable femur fracture may still benefit from a more rigid treatment.

While flexible intramedullary nailing (FIMN) is routinely recommended for length stable transverse diaphyseal femoral fractures in patients aged roughly 5-11 years old, there is lacking consensus amongst orthopaedists as to the recommended fixation method for length unstable femoral fractures for patients in this age range.

The motivation for this study is to identify the proper treatment modality for the subset of pediatric patients where there is lacking consensus amongst orthopaedists as to what the proper treatment method should be. We hope that our conclusions will streamline the decision-making process further for the patient’s designated physician and their family.

The objective of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of FIMN for pediatric diaphyseal length unstable femoral fractures in patients between the ages of 5 and 13. The effectiveness of FIMN for this subset of patients, named length unstable with FIMN, is then compared against 2 separate groups, one identified as length unstable with locked intramedullary nailing (IMN), submuscular plating (SMP), and external fixator, and the other being length stable with FIMN.

This is a retrospective study of patients belonging to one of the three groups mentioned above.

The study included 95 fractures from 92 patients, the group of interest, length unstable with FIMN, had 21 fractures, while 45 fractures were of the length stable with FIMN group, and 29 were in the length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, and external fixator group.

When examining patient details of the groups, length unstable with FIMN and length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, and external fixator, the first group had less blood loss (P < 0.05). In terms of complications, length unstable with FIMN had 9 total complications while length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, and external fixator had 10. When stratifying these complications as minor or major, length unstable with locked IMN, SMP, and external fixator had 6 major complication while length unstable with FIMN had 0 major complications (P < 0.05).

Comparing length unstable with FIMN (n = 21) and length stable with FIMN (n = 45), the complication rates were similar. As mentioned, length unstable with FIMN had 9 total complications, with 0 being major, while length stable with FIMN had 20 total complications, with 4 being major.

After analyzing the results from this single institution, retrospective comparative/ cohort study, we believe FIMN can be used for certain length unstable diaphyseal femoral fractures in patients between the ages of 5 and 13.

Future studies pertaining to this topic should collect patient reported outcomes for greater follow-up while also achieving a greater sample size of patients. Lastly, future studies should work to define the appropriate parameters and/or algorithm(s) necessary for deciding if a pediatric length unstable femur fracture may still benefit from a more rigid fixation method than FIMN.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pogorelic Z S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Stoneback JW, Carry PM, Flynn K, Pan Z, Sink EL, Miller NH. Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes After Submuscular Plating (SMP) of Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kocher MS, Sink EL, Blasier RD, Luhmann SJ, Mehlman CT, Scher DM, Matheney T, Sanders JO, Watters WC, Goldberg MJ, Keith MW, Haralson RH, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Sluka P, Hitchcock K. Treatment of pediatric diaphyseal femur fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rewers A, Hedegaard H, Lezotte D, Meng K, Battan FK, Emery K, Hamman RF. Childhood femur fractures, associated injuries, and sociodemographic risk factors: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e543-e552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kocher MS, Sink EL, Blasier RD, Luhmann SJ, Mehlman CT, Scher DM, Matheney T, Sanders JO, Watters WC, Goldberg MJ, Keith MW, Haralson RH, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Sluka P, McGowan R; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on treatment of pediatric diaphyseal femur fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1790-1792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sutphen SA, Beebe AC, Klingele KE. Bridge Plating Length-Unstable Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36 Suppl 1:S29-S34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soni JF, Schelle G, Valenza W, Pavelec AC, Souza CD. UNSTABLE FEMORAL FRACTURES TREATED WITH TITANIUM ELASTIC INTRAMEDULLARY NAILS, IN CHILDREN. Rev Bras Ortop. 2012;47:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sink EL, Hedequist D, Morgan SJ, Hresko T. Results and technique of unstable pediatric femoral fractures treated with submuscular bridge plating. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:177-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sink EL, Gralla J, Repine M. Complications of pediatric femur fractures treated with titanium elastic nails: a comparison of fracture types. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:577-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sink EL, Faro F, Polousky J, Flynn K, Gralla J. Decreased complications of pediatric femur fractures with a change in management. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:633-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li Y, Hedequist DJ. Submuscular plating of pediatric femur fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:596-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuremsky MA, Frick SL. Advances in the surgical management of pediatric femoral shaft fractures. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Samora WP, Guerriero M, Willis L, Klingele KE. Submuscular bridge plating for length-unstable, pediatric femur fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33:797-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ellis HB, Ho CA, Podeszwa DA, Wilson PL. A comparison of locked versus nonlocked Enders rods for length unstable pediatric femoral shaft fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:825-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Roaten JD, Kelly DM, Yellin JL, Flynn JM, Cyr M, Garg S, Broom A, Andras LM, Sawyer JR. Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures: A Multicenter Review of the AAOS Clinical Practice Guidelines Before and After 2009. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:394-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anderson SR, Nelson SC, Morrison MJ. Unstable Pediatric Femur Fractures: Combined Intramedullary Flexible Nails and External Fixation. J Orthop Case Rep. 2017;7:32-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Flinck M, von Heideken J, Janarv PM, Wåtz V, Riad J. Biomechanical comparison of semi-rigid pediatric locking nail versus titanium elastic nails in a femur fracture model. J Child Orthop. 2015;9:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Furlan D, Pogorelić Z, Biočić M, Jurić I, Budimir D, Todorić J, Šušnjar T, Todorić D, Meštrović J, Milunović KP. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing for pediatric long bone fractures: experience with 175 fractures. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:208-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | John R, Sharma S, Raj GN, Singh J, C V, Rhh A, Khurana A. Current Concepts in Paediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:353-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shaha J, Cage JM, Black S, Wimberly RL, Shaha SH, Riccio AI. Flexible Intramedullary Nails for Femur Fractures in Pediatric Patients Heavier Than 100 Pounds. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38:88-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cosma D, Vasilescu DE. Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nailing for Fractures in Children - Specific Applications. Clujul Med. 2014;87:147-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Allen JD, Murr K, Albitar F, Jacobs C, Moghadamian ES, Muchow R. Titanium Elastic Nailing has Superior Value to Plate Fixation of Midshaft Femur Fractures in Children 5 to 11 Years. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38:e111-e117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Salem KH, Keppler P. Limb geometry after elastic stable nailing for pediatric femoral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1409-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Flynn JM, Hresko T, Reynolds RA, Blasier RD, Davidson R, Kasser J. Titanium elastic nails for pediatric femur fractures: a multicenter study of early results with analysis of complications. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:4-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Narayanan UG, Hyman JE, Wainwright AM, Rang M, Alman BA. Complications of elastic stable intramedullary nail fixation of pediatric femoral fractures, and how to avoid them. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:363-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Windolf M, Fischer MF, Popp AW, Matthys R, Schwieger K, Gueorguiev B, Hunter JB, Slongo TF. End caps prevent nail migration in elastic stable intramedullary nailing in paediatric femoral fractures: a biomechanical study using synthetic and cadaveric bones. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:558-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Busch MT, Perkins CA, Nickel BT, Blizzard DJ, Willimon SC. A Quartet of Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nails for More Challenging Pediatric Femur Fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:e12-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tisherman RT, Hoellwarth JS, Mendelson SA. Systematic review of spica casting for the treatment of paediatric diaphyseal femur fractures. J Child Orthop. 2018;12:136-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Oh CW, Song HR, Jeon IH, Min WK, Park BC. Nail-assisted percutaneous plating of pediatric femoral fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;456:176-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hedequist DJ, Sink E. Technical aspects of bridge plating for pediatric femur fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:276-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hedequist D, Bishop J, Hresko T. Locking plate fixation for pediatric femur fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:6-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Eidelman M, Ghrayeb N, Katzman A, Keren Y. Submuscular plating of femoral fractures in children: the importance of anatomic plate precontouring. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kanlic EM, Anglen JO, Smith DG, Morgan SJ, Pesántez RF. Advantages of submuscular bridge plating for complex pediatric femur fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kanlic E, Cruz M. Current concepts in pediatric femur fracture treatment. Orthopedics. 2007;30:1015-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mileski RA, Garvin KL, Crosby LA. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in an adolescent following intramedullary nailing of the femur. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1706-1708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | O'Malley DE, Mazur JM, Cummings RJ. Femoral head avascular necrosis associated with intramedullary nailing in an adolescent. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:21-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Beaty JH, Austin SM, Warner WC, Canale ST, Nichols L. Interlocking intramedullary nailing of femoral-shaft fractures in adolescents: preliminary results and complications. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14:178-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hosalkar HS, Pandya NK, Cho RH, Glaser DA, Moor MA, Herman MJ. Intramedullary nailing of pediatric femoral shaft fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:472-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Abbott MD, Loder RT, Anglen JO. Comparison of submuscular and open plating of pediatric femur fractures: a retrospective review. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33:519-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Abdelgawad AA, Sieg RN, Laughlin MD, Shunia J, Kanlic EM. Submuscular bridge plating for complex pediatric femur fractures is reliable. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:2797-2807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sink EL. Submuscular Bridge Plating for Pediatric Femur Fractures. 2005;15:350-354 In: Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Rozbruch SR, Müller U, Gautier E, Ganz R. The evolution of femoral shaft plating technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;195-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ligier JN, Metaizeau JP, Prévot J, Lascombes P. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:74-77. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Siddiqui AA, Abousamra O, Compton E, Meisel E, Illingworth KD. Titanium Elastic Nails Are a Safe and Effective Treatment for Length Unstable Pediatric Femur Fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40:e560-e565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |