Published online Jun 18, 2020. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i6.294

Peer-review started: February 28, 2020

First decision: April 25, 2020

Revised: May 8, 2020

Accepted: May 19, 2020

Article in press: May 19, 2020

Published online: June 18, 2020

Processing time: 107 Days and 16.6 Hours

Tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) is a well-established surgical technique to deal with a stiff knee in revision total knee arthroplasty (RTKA). However, several reports have described potential osteotomy-related complications such as non-union, tibial tubercle migration and fragmentation, and metalware related pain.

To evaluate the literature and estimate the efficiency of TTO in RTKA in terms of osteotomy union, knee mobility and complications.

MEDLINE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were investigated for completed studies until February 2020. The principle outcome of the study was the incidence of union of the osteotomy. Secondary outcomes were the knee range of motion as well as the TTO-related and overall procedure complication rate.

Fifteen clinical studies with a total of 593 TTOs were included. The TTO union rate was 98.1%. Proximal migration and anterior knee pain were the most common TTO-related complications accounting for 6.9% and 6.4% of all cases, respectively. However, only 2.2% of cases suffering from anterior knee pain needed hardware removal. Knee flexion was improved from 82.9° preoperatively to 100.1° postoperatively and total knee range of motion was increased from 73.4° before surgery to 97° after surgery. Stiffness requiring manipulation under anesthesia was recorded in 4.6% of cases. No major complications were reported.

The current systematic review supports the use of TTO in RTKA, as it is associated with high union rate, significant improvement in knee motion and low osteotomy-related complication risk that rarely leads to secondary tibial tubercle procedures.

Core tip: Tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) is a useful technique to deal with a stiff knee in revision total knee arthroplasty. However, several reports have described potential osteotomy-related complications such as non-union, tibial tubercle migration and fragmentation as well as metalware related pain. The purpose of the current systematic review was to evaluate the literature and estimate the efficacy of TTO in revision total knee arthroplasty in terms of osteotomy union, knee range of motion, and complication rate. TTO was found to result in high union rate, significant improvement in knee motion and low osteotomy-related complication risk that rarely leads to secondary tibial tubercle procedures.

- Citation: Chalidis B, Kitridis D, Givissis P. Tibial tubercle osteotomy in revision total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. World J Orthop 2020; 11(6): 294-303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v11/i6/294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v11.i6.294

Tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) is a useful and well-established technique to deal with a tight extensor mechanism and stiffness in revision total knee arthroplasty (RTKA). It provides excellent exposure and visualization of the knee joint as it allows unforceful eversion or lateral subluxation of the patella and unimpeded access to the lateral gutter and lateral component-bone interface[1,2]. The osteotomized bone fragment should be of sufficient size to facilitate secure hardware fixation with wires and screws and provide an appropriate contact area for bone consolidation. Furthermore, preservation of the musculature sleeve is of primary importance for bone segment viability and stability and a good result can be achieved even after a previously performed TTO[2].

The osteotomy can be safely extended into the intramedullary tibial canal to utilize removal of the tibial stem and retained cement[3,4]. Although the intramedullary extension of the osteotomy may prolong union time due to the relatively small bone-to-bone contact area at the site of the TTO, good healing capacity has been reported[2]. In addition, re-alignment of the extensor mechanism for optimal balance and simultaneous correction of patellar height by proximalization of the tibial tubercle can be safely applied at the time of osteotomy fixation[2,3].

On the other hand, several reports have described potential osteotomy-related complications such as extensor lag, tibia fracture, nonunion, tibial tubercle migration, metalware irritation, and wire breakage. In the majority of cases, the aforementioned problems were largely attributed to surgical technique and adversely affected the functional outcome[5,6].

The current review aims to investigate the literature and estimate the efficiency of TTO in RTKA in terms of osteotomy union rate, knee range of motion (ROM), and incidence of complications.

The authors followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations[7].

MEDLINE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for entries from inception to February 2020. The search strategy for Medline was “(tibial tubercle osteotomy) AND (total knee)” and was adjusted to each database and no filters or language restrictions were used. The reference lists from the included articles were also manually screened for additional studies. Two authors (Kitridis D and Chalidis B) independently searched for studies and reviewed all titles and abstracts. Subsequently, the full texts were screened for eligible studies that met all identified inclusion criteria.

Clinical studies relevant to TTO in RTKA, which enrolled more than 10 patients over 18 years old, were included in the review. Trials with incomplete clinical data and articles reporting mixed results with primary total knee arthroplasty were excluded.

Two authors (Kitridis D and Chalidis B) performed the data extraction process from the selected articles in a blinded manner. Studies and patients’ characteristics (i.e., study type, year, country and size, as well as patients’ demographics), kind of surgical interventions, clinical results and complications, and the follow-up observations were gathered and analyzed. Any disagreement was resolved by review from a third author (Givissis P).

When there were insufficient data, these were requested from the corresponding author of each article.

Two investigators (Kitridis D and Chalidis B) independently performed the quality appraisal. Case series studies were assessed using the tool developed by Moga et al[8], which consists of 18 entries; studies achieving a score of 13 or greater are considered of high quality, 7-12 of moderate, and 0-6 of low quality. Comparative trials were evaluated using the Coleman Methodology Score[9], which relies to ten methodological criteria; a score of 100% is considered the optimal high quality score.

The main outcome of the review was the TTO union. Secondary outcomes were the improvement of ROM and the incidence of TTO-related and RTKA complications.

Pooled-data analysis was performed using weights according to each study’s sample size. Categorical outcomes were expressed as percentages. The longest follow-up measurements of each study were used. Microsoft Excel version 16 and IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 24 were utilized for data analysis.

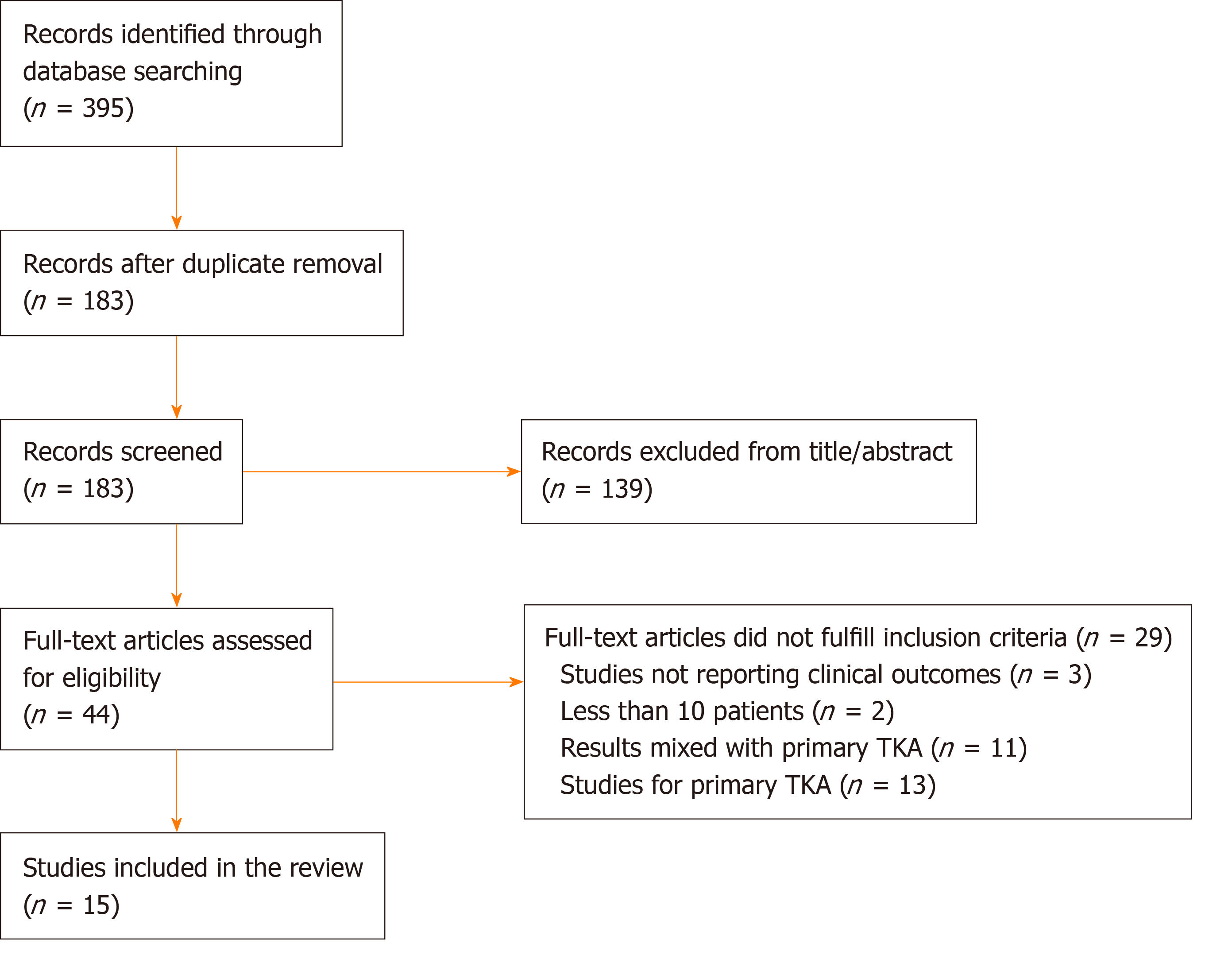

The literature search yielded 395 articles, of which 183 were duplicates and 139 were excluded from the titles and abstracts. Finally, 29 clinical studies did not fulfill the selection criteria and 15 clinical studies were considered for review (Figure 1).

Ten retrospective case series studies[1,2,4,6,10-15], three retrospective non-randomized comparative studies[3,16,17], one prospective non-randomized comparative trial[18], and one prospective randomized clinical trial[19] enrolled 780 patients. Data were extracted from a total of 545 patients, who underwent 593 TTOs. Of them, 296 were performed in aseptic RTKAs and 297 in septic RTKAs. Of note, eight studies included two-stage revisions for infected RTKAs[2-4,6,10,11,13,19]. All the cited articles were published from 1998 to 2019. Eight studies originated from Europe[1,6,12-16,19], five from North America[2,4,10,11,17], and two from Asia[3,18]. Tables 1 and 2 present details about studies and surgical interventions, respectively.

| Ref. | n | TTOs | Mean age (yr) | Males/ Females | Mean follow-up (mo) | Outcome measures |

| Barrack et al[17], 1998 | 15 | 15 | NR | NR | 30 (24-48) | ROM, KSS, Subjective satisfaction and function questionnaires |

| Bruni et al[19], 2013 | 39 | 39 | 72 ± 6 | 11/28 | 144 ± 24 | ROM, VAS, KSS, Complications |

| Chalidis et al[2], 2009 | 74 | 87 | 60 (29-89) | 35/39 | 49 (6-108) | ROM, Complications |

| Choi et al[10], 2012 (1) | 36 | 51 | 67 (38-87) | 20/16 | 57 (7-126) | ROM, KSS, Complications |

| Choi et al[11], 2012 (2) | 13 | 26 | 60 (38-85) | 9/4 | 56 (15-126) | ROM, KSS, Complications |

| Chun et al[18], 2019 | 31 | 31 | 73.8 ± 7.5 | 5/26 | 62.4 (36-210) | ROM, KSS, HSS, Complications |

| Hocking et al[1], 2007 | 52 | 52 | NR | NR | NR | ROM, KSS, Complications |

| Le Moulec et al[12], 2014 | 63 | 63 | 72 ± 11.3 | 29/36 | 27.8 ± 10.7 | ROM, IKS, Patellar height, Complications |

| Mendes et al[4], 2004 | 64 | 67 | 65.6 (35-93) | 25/39 | 30 (5-60) | ROM, KSS, Complications |

| Punwar et al[6], 2016 | 38 | 42 | 66 (33-92) | 24/14 | 6-24 | OKS, ROM, Walking status, Complications |

| Segur et al[13], 2014 | 26 | 26 | 73 (64-88) | 12/14 | 40.8 (28.8- 3.2) | KSS, WOMAC, ROM, Complications |

| Sun et al[3], 2014 | 21 | 21 | 70.1 ± 7.7 | 6/15 | 48.1 ± 17.2 | ROM, KSS, HSS, Complications |

| Van den Broek et al[14], 2006 | 37 | 37 | 54.2 (37-78) | NR | 28.4 (12-46) | ROM, KSS, VAS for satisfaction, Complications |

| Vandeputte et al[16], 2017 | 13 | 13 | 53.6 (34-71) | 5/8 | 24 | ROM, KSS, Complications |

| Zonnenberg et al[15], 2014 | 23 | 23 | 69.6 (43-84) | 7/16 | 16.1 (1-43) | KSS, ROM, SF-36, Complications |

| Ref. | TTO length (cm) | Fixation | Approach | Oscillating saw or osteotome |

| Barrack et al[17], 1998 | 10 | Wires | Medial parapatellar | Saw |

| Bruni et al[19], 2013 | 8-10 | Wires | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Chalidis et al[2], 2009 | 10.6 (7.9-15.3) | Wires (n = 16) | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Screws (n = 9) | ||||

| Wires and screws (n = 59) | ||||

| Choi et al[10], 2012 (1) | 8 | Wires (n = 49) | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Screws (n = 2) | ||||

| Choi et al[11], 2012 (2) | 8 | Wires (n = 25) | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Screws (n = 1) | ||||

| Chun et al[18], 2019 | 10 | Screws | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Hocking et al[1], 2007 | 5-8 | Wires | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Le Moulec et al[12], 2014 | 7.7 ± 1.6 | Wires | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Mendes et al[4], 2004 | 8-10 | Wires (n = 66) | Midvastus (n = 40) | Saw |

| Wires and screw (n = 1) | Medial parapatellar (n = 19) | |||

| Subvastus (n = 40) | ||||

| Not noted (n = 4) | ||||

| Punwar et al[6], 2016 | 7 | Screws | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Segur et al[13], 2014 | 10 | Wires (n = 25) | Medial parapatellar | Saw |

| Nonabsorbable sutures (n = 1) | ||||

| Sun et al[3], 2014 | 6-8 | Screws | Medial parapatellar | Saw |

| van den Broek et al[14], 2006 | 6-8 | Screws (n = 36) | Medial parapatellar | Both |

| Wires (n = 1) | ||||

| Vandeputte et al[16], 2017 | 6-8 | Wires or screws | Medial parapatellar | Saw |

| Zonnenberg et al[15], 2014 | 4-8 | Absorbable sutures | Medial parapatellar | Osteotome |

Ten studies were level IV evidence[1,2,4,6,10-15], four were level III[3,16-18], and one was level II[19]. Nine case series were found to be of high quality[2,4,6,10-15], and one of low quality[1]. The effect of the particular low-quality study was evaluated as a potential confounding factor; the stratified analysis of outcomes was repeated after excluding the study, and no substantial differences were noted (P = 0.83). Therefore, the study was finally included in the review. The comparative trials were rated with a mean Coleman Methodology Score[3,16-19] of 73.6% (range 54-92%).

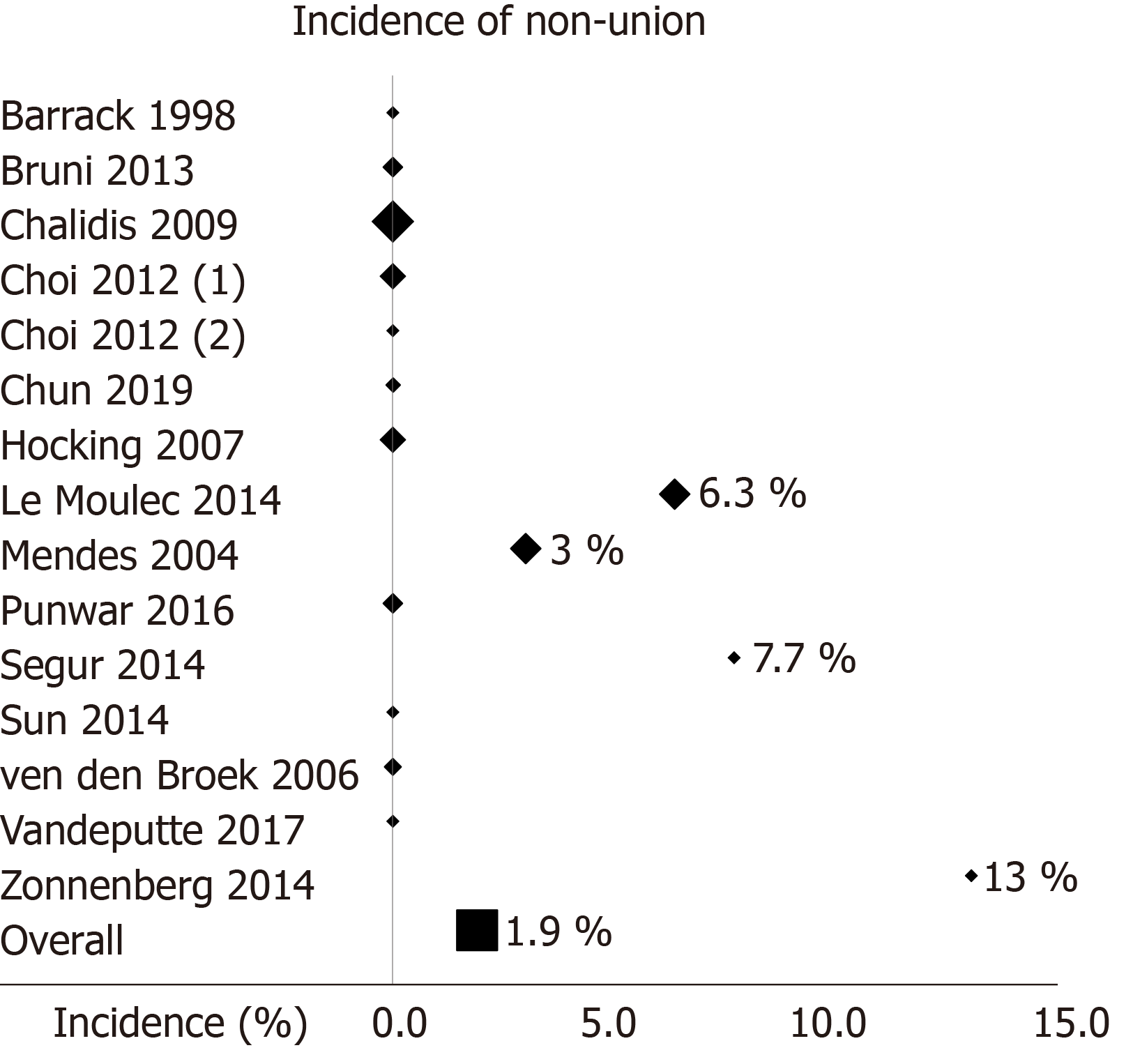

Eleven non-unions out of 593 TTOs were reported (union rate 98.1%, Figure 2). There were three intraoperative tibial tubercle (TT) fractures (0.5%), 10 proximal avulsion fractures (1.7%), and five metaphyseal tibial fractures (0.8%). Proximal migration of the TT was observed in 41 cases (6.9%). Anterior knee pain was reported in 38 cases (6.4%), 13 of which required hardware removal (2.2%). All TTO-related complications are reported in Table 3.

| Ref. | n | Non-unions | TT fractures | Proximal avulsion fractures | Metaphyseal tibial fractures | Proximal migration | Anterior knee pain |

| Barrack et al[17], 1998 | 15 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| Bruni et al[19], 2013 | 39 | - | - | - | - | - | 11 |

| Chalidis et al[2], 2009 | 74 | - | - | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Choi et al[10], 2012 (1) | 36 | - | - | 2 | 1 | 5 | - |

| Choi et al[11], 2012 (2) | 13 | - | - | - | - | 3 | - |

| Chun et al[18], 2019 | 31 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hocking et al[1], 2007 | 52 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 10 | - |

| Le Moulec et al[12], 2014 | 63 | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | - |

| Mendes et al[4], 2004 | 64 | 2 | - | - | 1 | 13 | 11 |

| Punwar et al[6], 2016 | 38 | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | - |

| Segur et al[13], 2014 | 26 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Sun et al[3], 2014 | 21 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 5 |

| van den Broek et al[14], 2006 | 37 | - | - | 1 | - | 2 | 3 |

| Vandeputte et al[16], 2017 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Zonnenberg et al[15], 2014 | 23 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

Total ROM improved from 73.4° preoperatively to 97° postoperatively and knee flexion increased from 82.9° before surgery to 100.1° after surgery. Data in detail are reported in Table 4.

| Ref. | n | Total ROM (°) | Flexion (°) | Extension lag | Flexion contracture | ||

| Preop | Postop | Preop | Postop | ||||

| Barrack et al[17], 1998 | 15 | 73 | 81 | 1.5° | |||

| Bruni et al[19], 2013 | 39 | 57 | 113 | 5 cases < 15° | |||

| Chalidis et al[2], 2009 | 74 | 60 | 95 | 80 | 95 | 2.5° | 2.5° |

| Choi et al[10], 2012 (1) | 36 | 40 | 92 | ||||

| Choi et al[11], 2012 (2) | 13 | 60 | 94 | 68 | 95 | 1° | |

| Chun et al[18], 2019 | 31 | 101 | 109 | 109 | 4° | ||

| Hocking et al[1], 2007 | 52 | 91 | 3 cases | ||||

| Le Moulec et al[12], 2014 | 63 | 87.8 | 103.7 | 15 cases | 10 cases | ||

| Mendes et al[4], 2004 | 64 | 101 | 107 | 3 cases < 15° | |||

| Punwar et al[6], 2016 | 38 | 85 | 95 | 15 cases | |||

| Segur et al[13], 2014 | 26 | 90 | 95 | 1 case < 5° | |||

| Sun et al[3], 2014 | 21 | 94.1 | 101.7 | 3.8° | |||

| van den Broek et al[14], 2006 | 37 | 81 | 93 | 1 case | |||

| Vandeputte et al[16], 2017 | 13 | ||||||

| Zonnenberg et al[15], 2014 | 23 | 87.9 | 95.3 | ||||

Stiffness requiring manipulation under anesthesia was evident in 27 cases (4.6%). From all RTKAs that performed due to periprosthetic joint infection via TTO, 29 knees (9.8%) showed recurrence of infection. None of the studies reported any major complications. Specifically, all non-TTO related complications are documented in Table 5.

| Ref. | Complications |

| Barrack et al[17], 1998 | None reported |

| Bruni et al[19], 2013 | MUA for stiffness (n = 3) |

| Reinfections (n = 2) | |

| DVT (n = 1) | |

| Chalidis et al[2], 2009 | MUA for stiffness (n = 10) |

| Skin necrosis (n = 1) | |

| Reinfections (n = 6) | |

| Choi et al[10], 2012 (1) | MUA for stiffness (n = 2) |

| Spacer subluxation (n = 1) | |

| Reinfections (n = 10) | |

| Choi et al[11], 2012 (2) | MUA for stiffness (n = 2) |

| Spacer subluxation (n = 1) | |

| Reinfections (n = 4) | |

| Chun et al[18], 2019 | Skin necrosis (n = 2) |

| Hocking et al[1], 2007 | MUA for stiffness (n = 4) |

| Le Moulec et al[12], 2014 | None reported |

| Mendes et al[4], 2004 | MUA for stiffness (n = 9) |

| Pain not associated to TTO (n = 2) | |

| Reinfection (n = 1) | |

| Delayed wound healing (n = 5) | |

| Transient peroneal nerve palsy (n = 3) | |

| Punwar et al[6], 2016 | Reinfections (n = 2) |

| Segur et al[13], 2014 | Reinfections (n = 3) |

| Sun et al[3], 2014 | Reinfection (n=1) |

| van den Broek et al[14], 2006 | None reported |

| Vandeputte et al[16], 2017 | None reported |

| Zonnenberg et al[15], 2014 | MUA for stiffness (n = 1) |

| Fractures of tibial plateau (n = 5) | |

| Patellar pain resolved with patellar resurfacing (n = 1) | |

| Wound leakage resolved conservatively (n = 5) |

The present systematic review advocates the use of TTO in RTKA. Knee flexion and ROM were improved from 82.9° and 73.4° preoperatively to 100.1° and 97° postoperatively, respectively. Furthermore, TTO permits early rehabilitation and restoration of quadriceps excursion and strength minimizing the incidence of extension lag[4]. Bruni et al[19] compared the utilization of TTO and Rectus Snip techniques at the time of reimplantation during two-stage RTKA for prosthetic joint infection. Patients in the TTO group had a higher mean Knee Society Score than the Rectus Snip group (88 vs 70, respectively). Mean maximum knee flexion was greater in the TTO group (113° vs 94°) with a lower incidence of extension lag (45% vs 13%). However, the risk of joint arthrofibrosis and stiffness even after utilization of TTO isn’t insignificant. We found that 4.6% of cases underwent postoperative closed manipulation under anesthesia to improve knee ROM.

Non-union of osteotomy is rare as 98.1% of bone healing was obtained. Even in case of tibial tubercle distalization or/and medialization for achieving proper tension and tracking of the patella and the extensor mechanism, excellent healing capacity should be expected[2,16]. Similarly, repeat osteotomy as well as intramedullary extension of osteotomy was associated with high union rates. Chalidis and Ries noticed that the median union time for the primary TTO was 15 wk (range 6 to 47 wk) and for the repeat TTO was 21 wk (range 7 to 27 wk)[2]. In addition, intramedullary TTO had a longer healing time (median 21 wk, range 7 to 38 wk) when compared to extramedullary osteotomy (median 12 wk, range 6 to 47 wk).

Proximal migration of TT and anterior knee pain were the most common complications of TTO with an incidence of 6.9% and 6.4%, respectively. Proximal step-cut osteotomy might prevent superior displacement of the osteotomized tibial fragment, although this was not necessarily associated with extensor mechanism dysfunction[2,14]. Anterior knee pain was mainly related to metalware prominence and irritation and it was apparent regardless the type of fixation with wires and screws[10,11]. However, we found that only 2.2% of cases required hardware removal. Suture repair may reduce even further the incidence of anterior knee pain but the technique relies on the integrity of the lateral periosteal sleeve and therefore risks migration of TTO[15,20].

Recurrence of periprosthetic knee joint infection was identified in 9.8% of RTKA cases. The overall risk appears to be a complex and multifactorial issue involving patient and surgical factors. Tibial tubercle osteotomy should be considered a safe extensile procedure as so far there is no evidence that the technique may adversely affect the possibility of reinfection. When TTO was compared to rectus snip regarding re-infections after two-stage revisions in infected RTKA, Bruni et al[19] reported that the results were similar in both groups (7% in the snip group and 5% in the TTO group, P = 0.84). Furthermore, Sun et al[3] in another comparative study found that the incidence of reinfection in two-stage RTKAs was 4.8% in the TTO group and 7.4% in the snip group. Nevertheless, this difference failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.71).

The main limitation of the current study was the fact that it was not feasible to conduct a meta-analysis with direct comparisons between interventions. This occurred because the majority of the included studies did not include a control group. Moreover, the case series studies were of low level of evidence. Another limitation was that the study by Zonnenberg et al[15] had a borderline moderate quality Coleman methodology score of 54%, and the study by Hocking et al[1] was of low quality according to the Moga score. After accounting for the risk of bias introduced in the review by the latter study with a stratified analysis, no significant changes of the results were noted compared to the primary analysis. Therefore, both studies were included to increase the sample size and improve the power of the review. Also, 13 out of 15 studies were retrospective, which might create data collection or patient selection bias. All these reflect the need for high-quality trials comparing different interventions.

In conclusion, TTO shows great clinical safety and efficacy in RTKA. Non-union is rare, and the most reported TTO-related complications are proximal migration and anterior knee pain. However, in the vast majority of cases they aren’t associated with secondary procedures of osteotomy refixation or metalware removal.

Tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) is a useful technique to deal with a stiff knee in revision total knee arthroplasty (RTKA). It provides excellent exposure and visualization of the knee joint as it allows unforceful eversion or lateral subluxation of the patella. Complications such as non-union, tibial tubercle migration and fragmentation, and metalware related pain have been reported.

Although TTO is widely utilized in RTKA, several reports have reported potential osteotomy-related complications. There is currently a lack of synthesis of the evidence about TTO in RTKA.

The present review aims to evaluate the available literature and estimate the efficiency of TTO in RTKA in terms of osteotomy union, knee mobility, and complications.

Medline, Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were systematically screened for studies from inception to February 2020. The main outcome was the incidence of union of the osteotomy. Secondary outcomes were the knee range of motion as well as the TTO-related and overall procedure complication rate. The systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA recommendations.

Fifteen clinical studies were included in the systematic review. Eleven non-unions out of 593 TTOs were reported (union rate 98.1%). Proximal migration of the TT was observed in 41 cases (6.9%). Anterior knee pain was reported in 38 cases (6.4%), 13 of which required hardware removal (2.2%). Total knee range of motion improved from 73.4° preoperatively to 97° postoperatively and knee flexion increased from 82.9° before surgery to 100.1° after surgery. Stiffness requiring manipulation under anesthesia was evident in 27 cases (4.6%).

TTO shows great clinical safety and efficacy in RTKA. Non-union is rare, and the most reported TTO-related complications are proximal migration and anterior knee pain. However, in the vast majority of cases they aren’t associated with secondary procedures.

Further clinical studies are encouraged to determine the optimal extensile approach in RTKA. High quality randomized studies comparing different techniques using standardized protocols will need to be performed.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: DeSousa K, Zhou YG S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Hocking RA, Bourne RB. Tibial tubercle osteotomy in revision total knee replacement. Tech Knee Surg. 2007;6:88-92. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chalidis BE, Ries MD. Does repeat tibial tubercle osteotomy or intramedullary extension affect the union rate in revision total knee arthroplasty? A retrospective study of 74 patients. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:426-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun Z, Patil A, Song EK, Kim HT, Seon JK. Comparison of quadriceps snip and tibial tubercle osteotomy in revision for infected total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2015;39:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mendes MW, Caldwell P, Jiranek WA. The results of tibial tubercle osteotomy for revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Divano S, Camera A, Biggi S, Tornago S, Formica M, Felli L. Tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) in total knee arthroplasty, is it worth it? A review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138:387-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Punwar SA, Fick DP, Khan RJK. Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy in Revision Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:903-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18665] [Cited by in RCA: 17476] [Article Influence: 1092.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Moga C, Guo B, Schopflocher D, Harstall C. Development of a quality appraisal tool for case series studies using a modified Delphi technique. Institute of Health Economics. 2012. [cited 20 February 2020]. Available from: https://www.ihe.ca/publications/development-of-a-quality-appraisal-tool-for-case-series-studies-using-a-modified-delphi-technique.html. |

| 9. | Coleman BD, Khan KM, Maffulli N, Cook JL, Wark JD. Studies of surgical outcome after patellar tendinopathy: clinical significance of methodological deficiencies and guidelines for future studies. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:2-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 764] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choi HR, Burke D, Malchau H, Kwon YM. Utility of tibial tubercle osteotomy in the setting of periprosthetic infection after total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2012;36:1609-1613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Choi HR, Kwon YM, Burke DW, Rubash HE, Malchau H. The outcome of sequential repeated tibial tubercle osteotomy performed in 2-stage revision arthroplasty for infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:1487-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Le Moulec YP, Bauer T, Klouche S, Hardy P. Tibial tubercle osteotomy hinged on the tibialis anterior muscle and fixed by circumferential cable cerclage in revision total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100:539-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Segur JM, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Martinez-Pastor JC, Macule F, Suso S, Acosta-Olivo C. Tibial tubercle osteotomy in septic revision total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1311-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | van den Broek CM, van Hellemondt GG, Jacobs WC, Wymenga AB. Step-cut tibial tubercle osteotomy for access in revision total knee replacement. Knee. 2006;13:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zonnenberg CB, van den Bekerom MP, de Jong T, Nolte PA. Tibial tubercle osteotomy with absorbable suture fixation in revision total knee arthroplasty: a report of 23 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:667-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vandeputte FJ, Vandenneucker H. Proximalisation of the tibial tubercle gives a good outcome in patients undergoing revision total knee arthroplasty who have pseudo patella baja. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:912-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Barrack RL, Smith P, Munn B, Engh G, Rorabeck C. The Ranawat Award. Comparison of surgical approaches in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;16-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chun KC, Kweon SH, Nam DJ, Kang HT, Chun CH. Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy vs the Extensile Medial Parapatellar Approach in Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty: Is Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy a Harmful Approach? J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2999-3003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bruni D, Iacono F, Sharma B, Zaffagnini S, Marcacci M. Tibial tubercle osteotomy or quadriceps snip in two-stage revision for prosthetic knee infection? A randomized prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1305-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Deane CR, Ferran NA, Ghandour A, Morgan-Jones RL. Tibial tubercle osteotomy for access during revision knee arthroplasty: Ethibond suture repair technique. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |