Published online Feb 18, 2020. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i2.137

Peer-review started: October 13, 2019

First decision: November 1, 2019

Revised: November 21, 2019

Accepted: December 23, 2019

Article in press: December 23, 2019

Published online: February 18, 2020

Processing time: 128 Days and 11.7 Hours

Peroneal tendon disorders are common causes of lateral hindfoot pain. However, total rupture of the peroneal longus tendon is rare. Surgical treatment for this condition is usually a side-to-side tenodesis of the peroneal longus tendon to the peroneal brevis tendon. While the traditional procedure involves a long lateral curved incision, this approach is associated with damage to the lateral soft tissues (up to 24% incidence).

A 50-year-old female had developed pain at the lateral aspect of the hindfoot 1 mo after an ankle sprain while walking in the street. Previous treatments were anti-inflammatory drugs, ice, rest and Cam-walker boot. At physical exam, there was pain and swelling over the course of the peroneal tendons. Ankle instability and cavovarus foot deformity were ruled out. Eversion strength was weak (4/5). Imaging showed complete rupture of the peroneal longus tendon associated with a sharp hypertrophic peroneal tubercle. Surgical repair was indicated after failure of conservative treatment (physiotherapy, rest, analgesics, and ankle stabilizer). A less invasive approach was performed for peroneal longus tendon debridement and side-to-side tenodesis to the adjacent peroneal brevis tendon, with successful clinical and functional outcomes.

Peroneus longus tendon tenodesis can be performed through a less invasive approach with preservation of the lateral soft tissue integrity.

Core tip: Traditionally, tenodesis of the peroneus longus tendon has been performed through a long lateral curved incision on the hindfoot. However, this approach is often associated with damage of the lateral soft tissues, having an incidence that ranges from 2.4% to 54%. The highlight of this study is its presentation of a less invasive approach for side-to-side tenodesis of full-thickness rupture of the peroneus longus tendon, which preserved most of the lateral soft tissue prone to wound breakdown.

- Citation: Nishikawa DRC, Duarte FA, Saito GH, de Cesar Netto C, Fonseca FCP, Miranda BR, Monteiro AC, Prado MP. Minimally invasive tenodesis for peroneus longus tendon rupture: A case report and review of literature. World J Orthop 2020; 11(2): 137-144

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v11/i2/137.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v11.i2.137

Acute peroneus longus tendon (PLT) ruptures are uncommon[1-3]. They rarely occur as an isolated injury, being more often associated with peroneus brevis tendon (PBT) partial or complete tears[4-6]. In general, the etiology involves mechanical and anatomical predisposing factors. An acute injury is the result of a sudden inversion sprain of the ankle. The most common sites of PLT lesions are where the tendon is subjected to attrition with underlying bones, such as the tip of the lateral malleolus, the peroneal tubercle, or the os peroneus[7-9]. Cavovarus deformity and lateral tibiotalar instability can also subject the PLT tendon to additional frictional forces on these points[1,4,10-12]. The six current options of treatment are nonoperative procedures, peroneal tendoscopy, opened debridement and tubularization of the remaining tendon, side-to-side tenodesis, tendon transfer of the flexor hallucis longus or flexor digitorum longus, and reconstruction with allograft or autograft[13-18]. Side-to-side tenodesis is considered an effective procedure for the treatment of partial or complete ruptures of the PLT, with successful results allowing patients to return to their previous activities[19]. However, this procedure has traditionally been performed through a long lateral curved incision that carries the risk of such soft tissue damage as dehiscence of the surgical wound, sural nerve transection, swelling, and infection[13,14].

The aim of this report was to describe the case of a patient who underwent a side-to-side tenodesis of the PLT to the PBT for the treatment of a full-thickness rupture of the PLT tendon using a minimally invasive approach. The approach was shown to be a reasonable option to preserve soft tissue on the lateral site of the hindfoot and ankle most prone to wound breakdown.

A 50-year-old female that works in a public hospital as a nurse assistant presented with complaints of severe pain and swelling on the right hindfoot along the course of the peroneal tendons (PT) after an ankle sprain.

The patient presented to the outpatient clinic of our hospital to address pain and swelling at the lateral aspect of the right hindfoot that had lasted for 1 mo after an ankle sprain while walking along the street. Previous treatments elsewhere were based on anti-inflammatory drugs, ice, rest and on the use of a Cam-walker boot (CWB).

The patient reported only hypertension as a chronic comorbidity.

Pain on palpation and swelling were evident over the course of the PT. No clinical signs of ankle instability were observed under stress maneuvers (anterior drawer and talar tilt tests). A subtle bilateral and symmetrical cavovarus foot was noted. Weakness in eversion was present under resistance, with strength of 4/5.

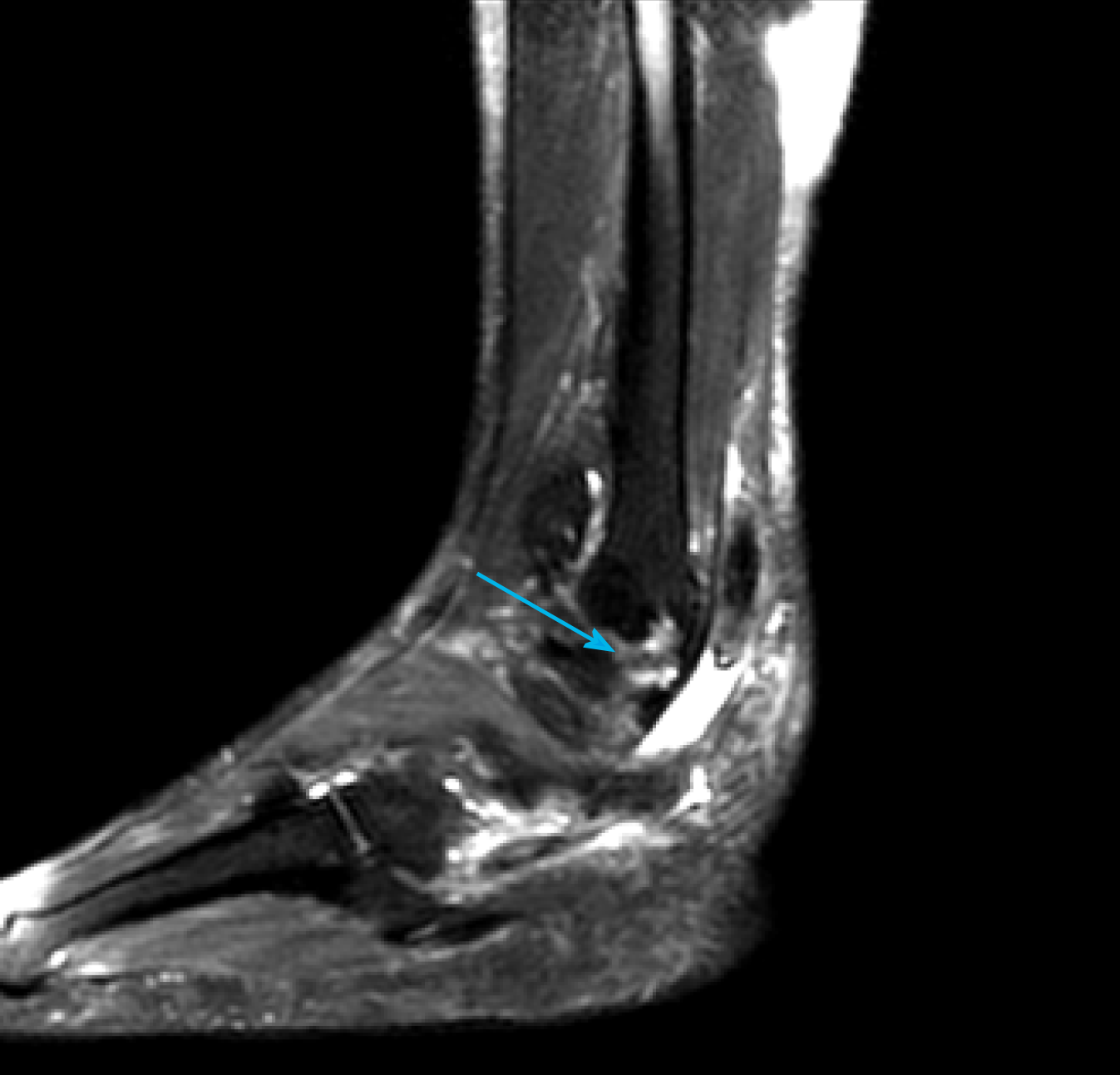

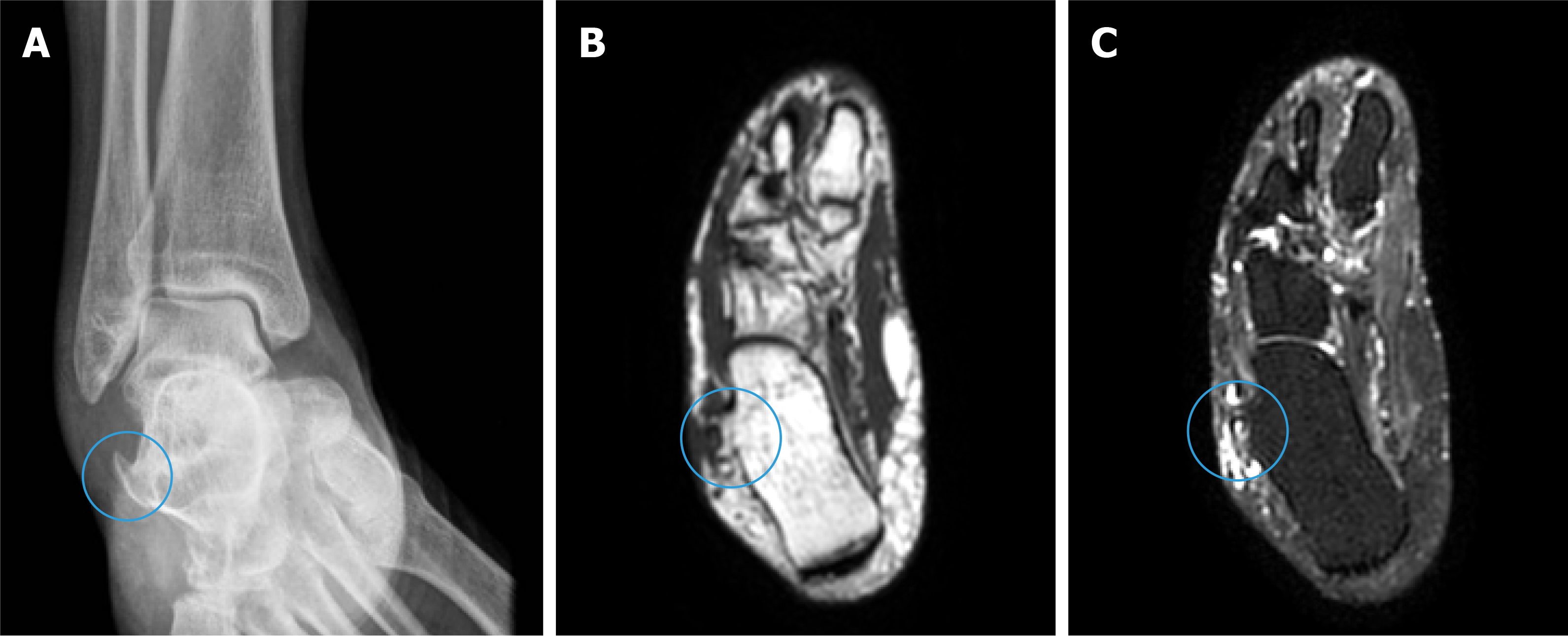

Foot and ankle plain radiographic series imaging and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ankle were performed. MRI T2-weighted images showed complete rupture of the PLT, surrounded by extensive synovitis (Figure 1). With plain radiographic images of the ankle anteroposterior view and the MRI T1- and T2-weighted images, it was possible to identify a sharp hypertrophic peroneal tubercle (Figure 2). An MRI exam of the leg was carried out to evaluate the status of the peroneal muscles and to determine if there was any evidence of fatty infiltration and/or muscle atrophy.

Full-thickness rupture of the PLT associated with a sharp hypertrophic peroneal tubercle.

Surgical repair was indicated after 6 mo of failure of the conservative treatment (physiotherapy, rest, anti-inflammatory drugs, and ankle stabilizer to restrict inversion-eversion movements). Preoperatively, the visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain and the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) ankle-hindfoot scores were applied. The patient’s VAS score was 9 and AOFAS ankle-hindfoot score was 39.

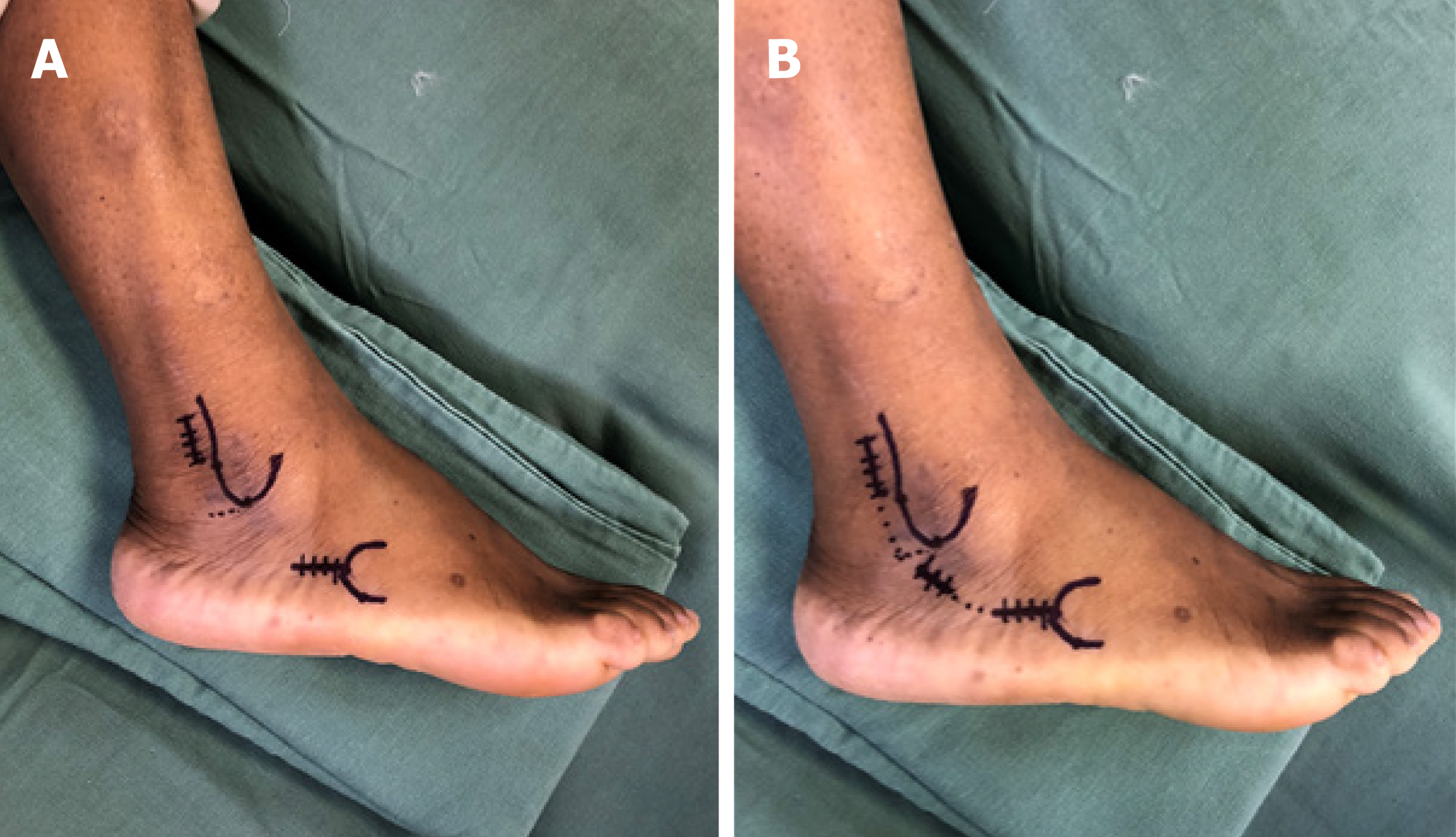

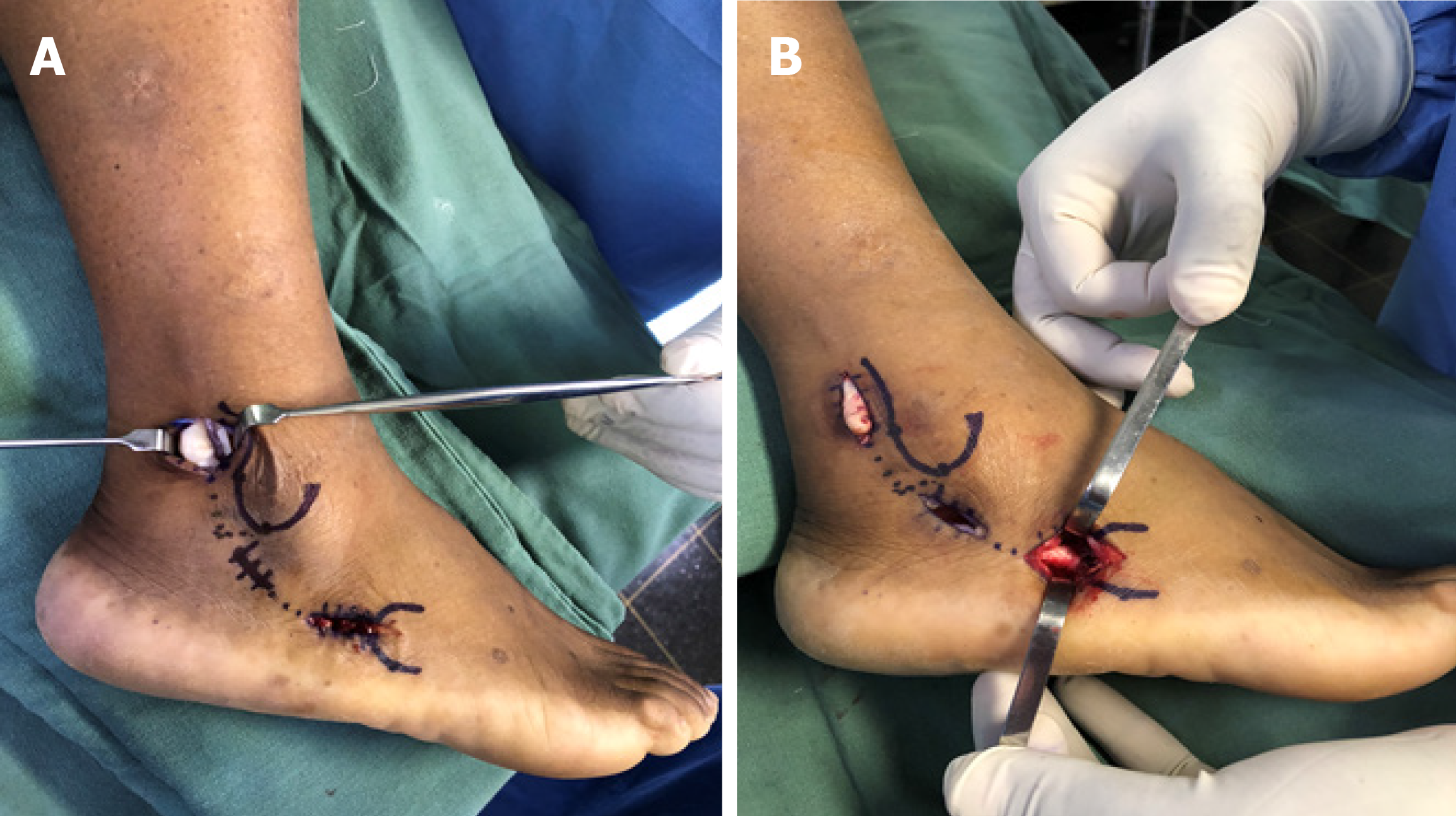

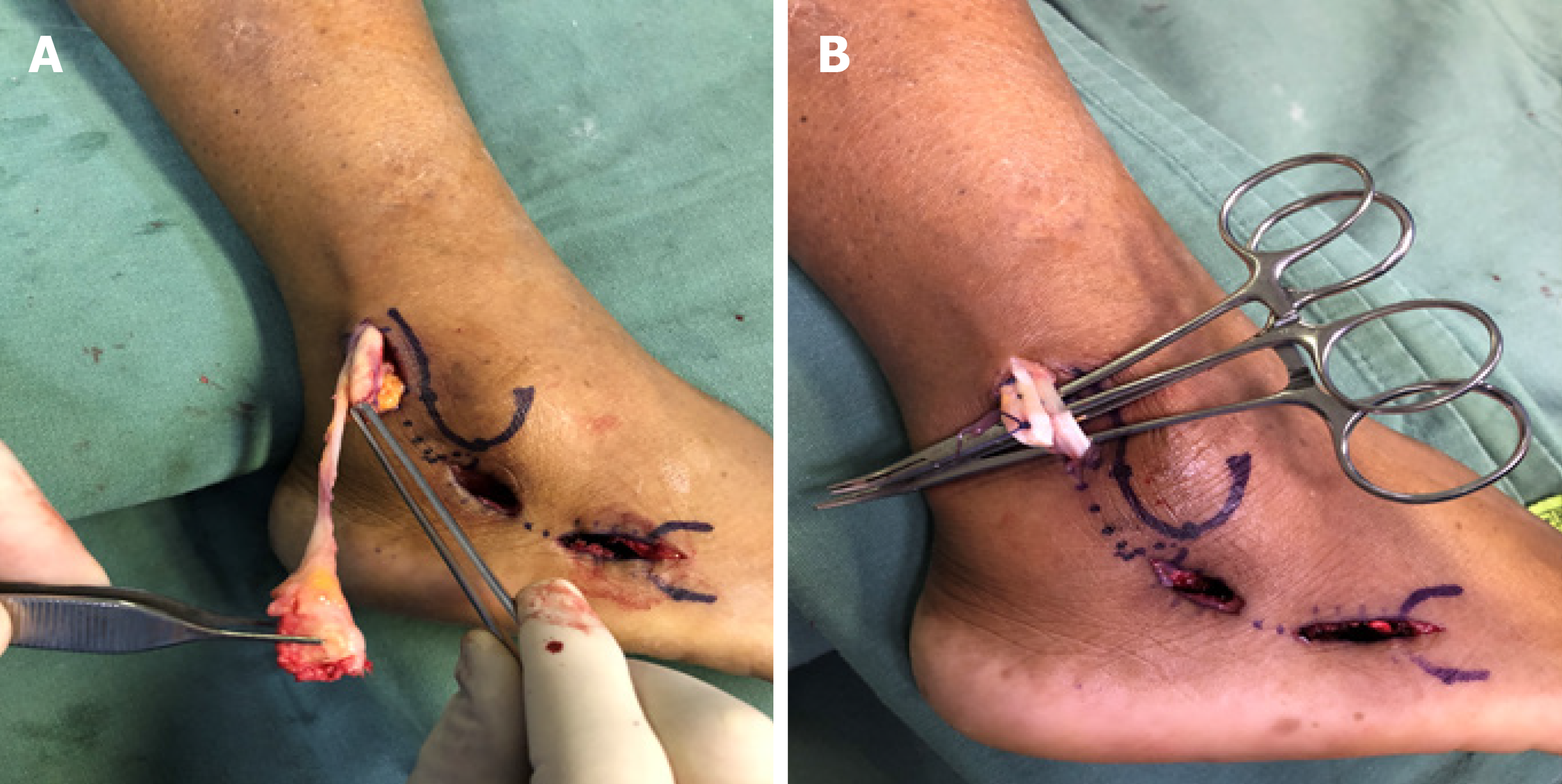

The surgical procedure was performed under regional anesthesia, with the patient placed in a lateral position using a well-padded nonsterile thigh tourniquet inflated to 300 mmHg. The minimally invasive approach consisted of two short incisions (Figure 3). Anatomical references were marked with a Codman skin marking pen and included lateral malleolus and base of the fifth metatarsal. Proximally, a longitudinal incision of approximately 3 cm in length was made at 1 cm posterior to the posterior border of the distal fibula and 1.5 cm above the tip of the lateral malleolus. The PT sheath was dissected and opened to expose the proximal portion of the PLT but the superior peroneal retinaculum remained intact (Figure 4). Care was taken to avoid the sural nerve and the lesser saphenous vein that runs laterally to the Achilles tendon[20,21]. Distally, a longitudinal incision of 3 cm in length was made parallel to the ground, going backwards from the tip of the base of the fifth metatarsal base. In the distal incision, the distal stump of the remaining PLT was dissected and released at the cuboid groove. Due to the presence of a hypertrophic peroneal tubercle, a short middle incision of 2 cm was made for its resection (Figure 3B). The PLT was then brought out of its sheath through the proximal incision, and its nonviable portion was resected (Figure 4A). After debridement of the PLT, the remaining proximal stump of the native PLT was sutured side-to-side to the PBT with two U-shaped lateral sutures using No. 1 Vicryl (Ethicon Inc, Johnson & Johnson, Bridgewater, NJ, United States) (Figure 4B). This suture was made above the superior peroneal retinaculum to prevent volume effect of increased pressure within the retromaleolar groove (Figure 5). Finally, the three incisions were closed in layers. In the proximal incision, the PT sheath was closed with No. 1 Vicryl, the subcutaneous tissue with No. 3 Monocryl (Ethicon Inc, Cornelia, GA, United States), and the skin with No. 4 nylon. In the middle and distal incisions, the subcutaneous tissue was closed with No. 3 Monocryl and the skin with No. 4 nylon. After closure of the surgical wounds, a sterile soft dressing and a splint were applied with the foot in the neutral position.

The patient remained nonweight-bearing for 2 wk with the cast. After 2 wk, the sutures were removed and full weight-bearing was allowed as tolerated with a CWB. Concerning evolution of the surrounding soft tissues and surgical wound, no complications of healing were noted. Sensitivity of the lateral skin of the hindfoot was preserved and similar to the contralateral foot. At that time, physical therapy was initiated, focusing on dorsiflexion/plantarflexion range of motion to prevent adhesions. Inversion/eversion movements were prohibited to prevent rupture of the suture of the tenodesis. The patient was instructed to always maintain the CWB, except for hygiene purposes and dorsiflexion/plantarflexion exercises. At 6 wk postoperative, the patient was out of the CWB with minimal swelling, and inversion/eversion movements were allowed; the patient was transitioned into an ankle stabilizing orthosis. From that point, the physical therapy program was oriented for inversion/eversion movements and to progressively restore proprioception and strength. The ankle stabilizing orthosis was used progressively less, according to the patient’s rehabilitation.

At 12 wk of follow-up, physical examination revealed that there was no pain on palpation or restriction of inversion. Surgical incisions were fully healed, and swelling had decreased significantly (Figure 6). The patient presented VAS score of 0 and AOFAS ankle-hindfoot score of 90. At 6 mo of follow-up, the patient finished physiotherapy and returned to her prior level of activities. In physical examination, there was still no pain and peroneal strength was 5/5. The VAS score was 0 and AOFAS ankle-hindfoot score was 98. At 14 mo of follow-up, the patient reported that she was feeling great, with no complaints, and was fully active.

Treatment of complete rupture of the PLT is based on patient symptoms, such as pain, loss of function, or instability. Inactive and asymptomatic patients can be treated conservatively. However, in cases of active and symptomatic patients, the outcomes of nonsurgical management are poor, with the need of surgical treatment to provide pain relief and to support return to prior level of activities[5,22-26]. Tenodesis of the proximal stump of the ruptured PLT to the intact PBT has been described and widely used for this type of injury, with satisfactory clinical and functional outcomes[1,27]. However, this procedure has traditionally been performed through a long lateral curved incision from the lateral retromaleolar area to the base of the fifth metatarsal[11,28]. This longer lateral approach is often associated with damage to the lateral soft tissues, resulting in scar tenderness, sural nerve lesion, wound dehiscence, swelling, adhesive tendinitis, subluxation of the PT, and infection.

These complications are reported in the literature in an incidence that ranges from 2.4% to 54%[13,14,23,29]. In a study involving 30 patients treated for PT tears through the same long lateral approach, Steel et al[29] showed that 58% of the patients had scar tenderness, 54% presented lateral ankle swelling, 27% had numbness over the lateral surface of the ankle, and 31% had pain at rest. Likewise, Redfern et al[23] reported postoperative complications in 31% (9/28) of patients treated for concomitant tears of PBT and PLT through the same long lateral incision. Three developed superficial wound infections, one wound dehiscence, two sural neuritis, one complex regional pain syndrome, and one adhesive tendinitis. Here, we have presented the case of a symptomatic patient with a full-thickness rupture of the PLT that was successfully treated with side-to-side tenodesis of the PLT to the PBT, without any soft tissue compromise in the postoperative follow-up. To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe a less invasive approach for the PLT tenodesis procedure.

The main advantage of our technique was that it allowed for performance of tenodesis of the PLT to PBT through two separate short incisions, with less aggression to the surrounding soft tissue. We were able to keep the integrity of deep structures, such as the superior peroneal retinaculum, giving us confidence to orient early mobilization of the ankle and avoiding additional scar tissue that may restrict the tenodesis suture gliding or postoperative luxation of the peroneal tendon. Consequently, all this care with the soft tissue integrity provided less pain in the postoperative period, faster healing of the wound, and faster recovery. The indication of our technique can be extended to the group of patients at higher risk of wound complications, such as diabetics, smokers, and vasculopaths.

Both incisions were designed to be easily complemented with other incisions in case a patient requires additional procedures, such as lateral ligament reconstruction, calcaneal osteotomy for varus realignment, or hypertrophic peroneal tubercle (HPT) resection. Our proximal approach does not interfere in the curved incision along the anteroinferior margin of the fibula for the Brostrom-Gould reconstruction, the lateral oblique incision at the hindfoot for calcaneal osteotomy, and an additional short incision, which can be performed for resection of the HPT. In this particular case, the authors decided on HPT removal because it was much more prominent than the usual images from overall patients and it presented with bone edema beneath (in MRI, indicating friction between the HPT itself and the PT). In fact, we believe that this was the etiologic factor since lateral ligaments were still present in the MRI images and at physical exam the patient did not present a significant cavovarus foot. An enlarged peroneal tubercle interferes with the normal gliding of the PLT[6,15,30]. Literature has advised for excision of HPT since it may predispose tenosynovitis and recurrent tears of the PT[15].

In conclusion, the minimally invasive approach described herein should be considered for surgical treatment of PLT, such as tenodesis. It represents a simple and effective alternative to the long lateral curved incision. With two short incisions, it preserves soft tissue integrity above the PT course. Besides that, it can be useful for those patients at higher risk of wound breakdown. Further studies analyzing clinical and functional outcomes in a larger population and with longer follow-up are needed to determine the precise roles of this technique in treatment of PLT.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Garg R, Teragawa H S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Koh D, Liow L, Cheah J, Koo K. Peroneus longus tendon rupture: A case report. World J Orthop. 2019;10:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Borton DC, Lucas P, Jomha NM, Cross MJ, Slater K. Operative reconstruction after transverse rupture of the tendons of both peroneus longus and brevis. Surgical reconstruction by transfer of the flexor digitorum longus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:781-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Molloy R, Tisdel C. Failed treatment of peroneal tendon injuries. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:115-129, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roster B, Michelier P, Giza E. Peroneal Tendon Disorders. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34:625-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arbab D, Tingart M, Frank D, Abbara-Czardybon M, Waizy H, Wingenfeld C. Treatment of isolated peroneus longus tears and a review of the literature. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7:113-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Cerrato RA, Myerson MS. Peroneal tendon tears, surgical management and its complications. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009;14:299-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Petersen W, Bobka T, Stein V, Tillmann B. Blood supply of the peroneal tendons: injection and immunohistochemical studies of cadaver tendons. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brandes CB, Smith RW. Characterization of patients with primary peroneus longus tendinopathy: a review of twenty-two cases. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grant TH, Kelikian AS, Jereb SE, McCarthy RJ. Ultrasound diagnosis of peroneal tendon tears. A surgical correlation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1788-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Davda K, Malhotra K, O'Donnell P, Singh D, Cullen N. Peroneal tendon disorders. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2:281-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heckman DS, Gluck GS, Parekh SG. Tendon disorders of the foot and ankle, part 1: peroneal tendon disorders. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:614-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Squires N, Myerson MS, Gamba C. Surgical treatment of peroneal tendon tears. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007;12:675-695, vii. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Seybold JD, Campbell JT, Jeng CL, Short KW, Myerson MS. Outcome of Lateral Transfer of the FHL or FDL for Concomitant Peroneal Tendon Tears. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:576-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Demetracopoulos CA, Vineyard Vineyard JC, Kiesau CD, Nunley JA 2nd. Long-term results of debridement and primary repair of peroneal tendon tears. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35:252-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Dijk PA, Miller D, Calder J, DiGiovanni CW, Kennedy JG, Kerkhoffs GM, Kynsburtg A, Havercamp D, Guillo S, Oliva XM, Pearce CJ, Pereira H, Spennacchio P, Stephen JM, van Dijk CN. The ESSKA-AFAS international consensus statement on peroneal tendon pathologies. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:3096-3107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pellegrini MJ, Adams SB, Parekh SG. Allograft reconstruction of peroneus longus and brevis tendons tears arising from a single muscular belly. Case report and surgical technique. Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;21:e12-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mook WR, Parekh SG, Nunley JA. Allograft reconstruction of peroneal tendons: operative technique and clinical outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34:1212-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cody EA, Karnovsky SC, DeSandis B, Tychanski Papson A, Deland JT, Drakos MC. Hamstring Autograft for Foot and Ankle Applications. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39:189-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rapley JH, Crates J, Barber A. Mid-substance peroneal tendon defects augmented with an acellular dermal matrix allograft. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31:136-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Duscher D, Wenny R, Entenfellner J, Weninger P, Hirtler L. Cutaneous innervation of the ankle: an anatomical study showing danger zones for ankle surgery. Clin Anat. 2014;27:653-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | De Maeseneer M, Madani H, Lenchik L, Kalume Brigido M, Shahabpour M, Marcelis S, de Mey J, Scafoglieri A. Normal Anatomy and Compression Areas of Nerves of the Foot and Ankle: US and MR Imaging with Anatomic Correlation. Radiographics. 2015;35:1469-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sammarco GJ. Peroneus longus tendon tears: acute and chronic. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:245-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Redfern D, Myerson M. The management of concomitant tears of the peroneus longus and brevis tendons. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:695-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dombek MF, Lamm BM, Saltrick K, Mendicino RW, Catanzariti AR. Peroneal tendon tears: a retrospective review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2003;42:250-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bassett FH, Speer KP. Longitudinal rupture of the peroneal tendons. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:354-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wind WM, Rohrbacher BJ. Peroneus longus and brevis rupture in a collegiate athlete. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:140-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Slater HK. Acute peroneal tendon tears. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007;12:659-674, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Stamatis ED, Karaoglanis GC. Salvage options for peroneal tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2014;19:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Steel MW, DeOrio JK. Peroneal tendon tears: return to sports after operative treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Palmanovich E, Laver L, Brin YS, Kotz E, Hetsroni I, Mann G, Nyska M. Peroneus longus tear and its relation to the peroneal tubercle: A review of the literature. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2011;1:153-160. [PubMed] |