Published online Dec 18, 2020. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i12.615

Peer-review started: April 1, 2020

First decision: September 29, 2020

Revised: September 29, 2020

Accepted: October 29, 2020

Article in press: October 29, 2020

Published online: December 18, 2020

Processing time: 257 Days and 11.5 Hours

Few cases of avulsion fractures of the tibial tuberosity with simultaneous rupture of the patellar tendon have been reported in the literature. Therefore, its mechanism and incidence have not been determined conclusively. This type of fracture is considered a serious injury that requires prompt diagnosis and early surgical repair. There is no therapeutic algorithm or standard method of treatment due to the infrequency of the injury. In this case report, we conducted an exhaustive review and synthesis of the existing literature including all previously reported cases.

We present a 16-year-old male soccer player with a case of a tibial tuberosity fracture with distal avulsion of the patellar tendon 5 d prior to surgical treatment. The patient presented with a loss of the extensor mechanism of the knee, edema, the inability to walk, and pain. X-rays showed a high patella and a 180-degree avulsion of the tibial tuberosity. The diagnosis was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography. The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture with a cannulated screw and washer as well as patellar tendon repair with two metallic anchors. The rehabilitation protocol consisted of initial immobilization in extension followed by passive mobility and muscle strengthening exercises. The patient demonstrated excellent postoperative outcomes and returned to regular activity without complications.

This case presentation and literature review comprise the most relevant clinical, radiographic, and treatment details described in the international literature to date, providing the reader with an overview of this rare condition.

Core Tip: Simultaneous injury to the anterior tibial tuberosity and the patellar tendon is rare, and the etiology is unclear. To date, no definitive treatment protocols for this pathology have been reported. In this case report, we present a review of the studies published to date. The diagnoses must be based on high clinical suspicion, physical examinations, and imaging methods. Open reduction and internal fixation of the bone fragment are almost always necessary. Patellar tendon repair is performed using sutures, anchors, staples, or screws.

- Citation: Morales-Avalos R, Martínez-Manautou LE, de la Garza-Castro S, Pozos-Garza AJ, Villarreal-Villareal GA, Peña-Martínez VM, Vílchez-Cavazos F. Tibial tuberosity avulsion-fracture associated with complete distal rupture of the patellar tendon: A case report and review of literature. World J Orthop 2020; 11(12): 615-626

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v11/i12/615.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v11.i12.615

Avulsion fractures of the tibial tuberosity (TT) are uncommon, accounting for less than 1% of all physeal injuries[1] and 0.4%-2.7% of epiphyseal injuries. The incidence of patellar tendon (PT) rupture in the pediatric population is unclear[2,3]. Only a few cases of avulsion fracture of the TT with a complete simultaneous rupture of the PT have been reported in the literature[4]; therefore, the mechanism and incidence of this type of fracture have not been clearly determined[5]. Some previous studies have suggested that it may be related to certain enzymatic deficiencies, obesity or Osgood-Schlatter disease[5].

Watson-Jones[6] was the first to classify TT fractures into three different types. Subsequently, Ogden et al[7]further modified this classification system in 1980 by looking at other parameters that impacted management, including displacement and comminution, and added subtypes A and B. Then Frankl et al[8] extended the classification system to include the association with PT ruptures.

Although rare, avulsion fractures of the TT are considered serious injuries that necessitate a prompt diagnosis and early surgical repair. There are relevant differences among the treatments proposed by various authors, most of which are surgical treatments. However, there is no therapeutic algorithm or standard method of treatment due to the infrequency of the injury[9]. The authors present a case of TT fracture with distal avulsion of the PT that occurred in a 16-year-old amateur soccer player who was surgically treated, as well as a comprehensive review of the existing literature on the injury. The authors have obtained written informed consent from the patient and his parents to print and electronically publish the case report and in this case report no data is shown that could lead to the identification of the patient.

A 16-year-old male soccer player on an amateur team who was a resident of a rural community with limited access to medical services presented to the trauma emergency room with a 6 d history of evolution, pain, swelling in the left knee and the inability to bear weight.

The patient’s injury occurred while he was playing soccer; his right leg was fixed in extension when he kicked a ball with his left foot. Subsequently, the patient experienced severe pain in the left knee, fell directly onto the ground from a standing position, and could not bear weight on the foot. He was immobilized and treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), rested and physical measures; however, when the symptoms persisted, the patient was transferred to our trauma center. He was initially assessed in our center 6 d after the incident.

The patient had no significant previous illnesses.

The patient exhibited grade 2 obesity (weight: 102 kg, height: 1.65 cm, body mass index: 37.50 kg/m2), and there were no relevant items in the medical history.

In the examination, the skin on the left knee was intact, without abrasions or wounds, and the patient showed a diffuse increase in soft tissue around the left knee, moderate joint effusion (grade 3), and a knee attitude in flexion. He was also unable to actively perform knee extension. The patient experienced severe pain during palpation of the TT (8/10 in the visual analogue scale). The injured patella was also asymmetrically elevated compared to the contralateral patella (Figure 1). The Lachman test result was negative, and no knee instability was confirmed on the physical exam. Distally, he demonstrated to the ability to completely plantarflex and dorsiflex the ankle and flex and extend the fingers.

This patient had routine blood tests including complete blood count, blood clotting, blood group, basic metabolic panel, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate tests. These results did not reveal any abnormalities.

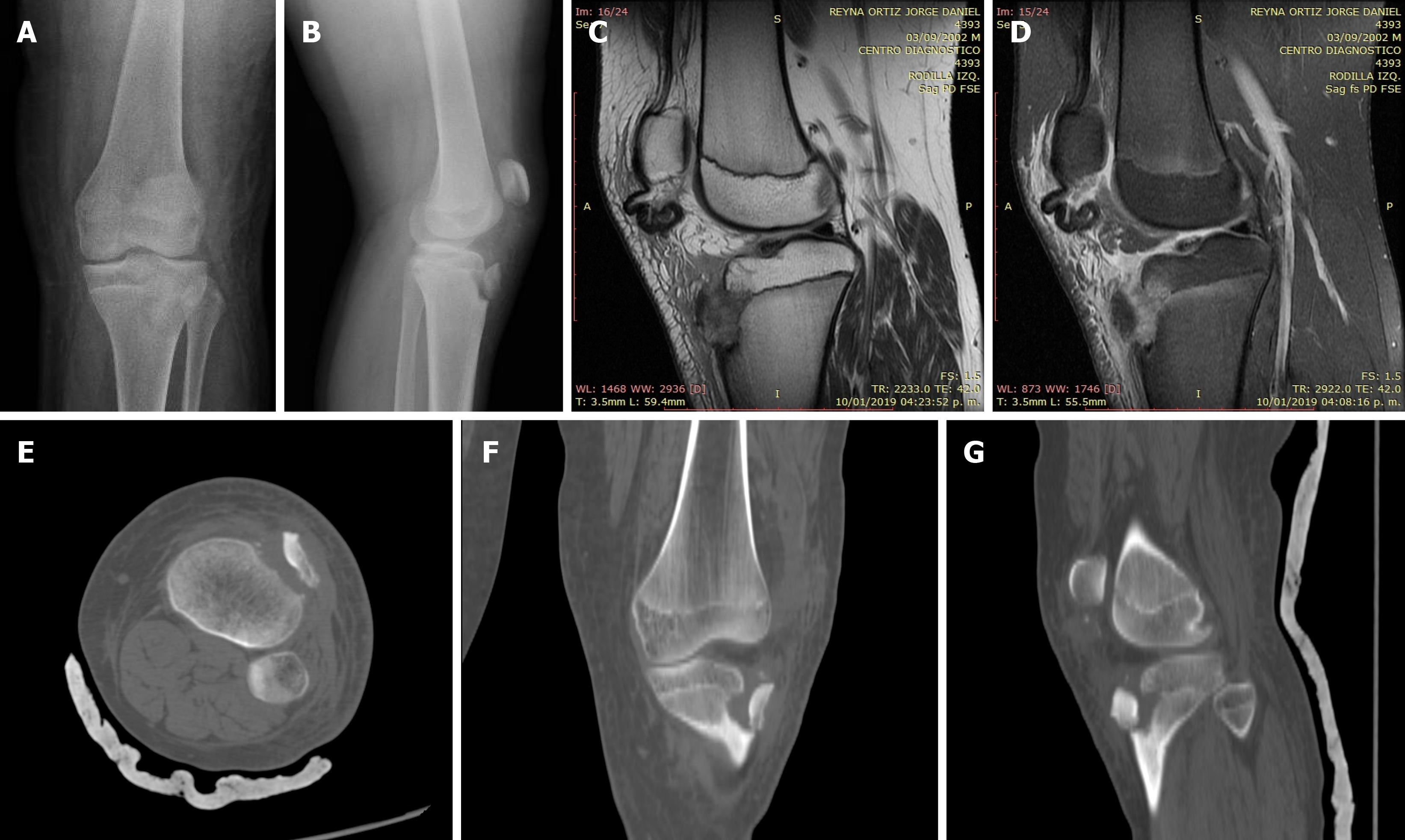

The radiographs revealed a displaced avulsion fracture of the TT extending to the level of the proximal tibial physis (Ogden type 2B) with 180º of rotation in the fragment and a concomitant high-riding patella (Caton-Desahmps index: 1.47) (Figure 2A and B). Given the latter finding, concern was raised for PT injury; a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was performed, and the results demonstrated a complete distal rupture of the PT (which was retracted in the lower pole of the patella) (Figures 2C and D), reclassifying the lesion as an Ogden 2C type lesion. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the knee was performed, which revealed a large anterior fragment displaced by 13.14 mm (Figures 2E and F).

The final diagnosis was an avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity and total distal rupture of the patellar tendon (simultaneous injury at two sites of the extensor mechanism).

The patient’s left lower extremity was placed into a bulky jones dressing with a knee immobilizer, and the patient was admitted to the hospital. He was taken to the operating room the following day for open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture and repair of the tendon injury.

After the induction of spinal anesthesia, prophylactic antibiotics were administered (cephalotin 1-gram I.V.). The patient was positioned supine on a radiolucent table without a tourniquet due to possible retraction that can affect the patellar and quadricipital tendons. After sterile preparation and draping with the knee in 30º of flexion, an anterior longitudinal incision measuring 7 cm was made over the anterior aspect of the knee, extending from the distal pole of the patella to 3 cm below the TT (Figure 3A). Dissection was performed through the subcutaneous tissue to the extensor mechanism, where the fracture and hematoma were encountered (Figure 3B).

After the hematoma was drained, the infrapatellar fat pad was identified and debrided from the fibrotic tissue. Then the PT was identified and completely avulsed from its distal native footprint (Figure 3C). Macroscopically, the PT appeared delaminated and frayed without any intratendinous ruptures. The PT was located for later reconstruction. Then the TT was found to be a completely free fragment, rotated by 180º and displaced from its original position (Figure 3D). The anterior cortex of the TT was devoid of periosteum at the patellar tendon insertional footprint (consistent with a tendon avulsion), while some ruptured terminal tendon fibers remained attached to the tubercle. The tubercle’s periosteum was found to be attached to the undersurface of the ruptured patellar tendon.

The free TT fracture edges were cleared of soft tissue, and the hematoma was removed. Under fluoroscopic assistance, the TT was correctly reduced. With a 0.045-inch K-wire, the reduction was secured (Figure 3E), and a half-threaded 6.5 mm × 50 mm cannulated screw (DePuy Synthes®, West Chester, PA, United States) and washer were used (Figure 3F). Subsequently, PT reconstruction was initiated. With the knee in 30º of flexion, the PT was reduced to its original footprint over the TT. The periosteum attached to the undersurface of the tendon was reapproximated onto its footprint on the tibial tubercle and was thus used as an anatomic landmark to ensure the appropriate tensioning of the PT. If this maneuver was not possible, a peroneus longus allograft was prepared. Subsequently, two 5.5 mm metallic anchors (Corkscrew; Arthrex®, Naples, FL, United States), with two high resistance sutures per anchor, were placed 2.5 cm distal to the TT; one anchor was placed medial to the TT, and one anchor was placed lateral to the TT (Figure 3G). Subsequently, one high-resistance suture of the medial anchor was used to perform a Krackow suture on the PT. A total of seven passes were performed, and the free ends of the suture were knotted. Then, one suture was used as the lateral anchor, a Krackow suture was performed on the PT, with a total of 7 passes, and the free ends of the suture were knotted. The other two high-resistance sutures were used to repair the medial and lateral retinacula of the PT (Figure 3H). The duration of the surgery was 58 min. Finally, radiographic images were taken to confirm the patella height was correct according to the Caton-Deshamps index (Figures 3I and J). The wound was irrigated, and a multilayered closure was performed (Figure 3K). The knee was immobilized with an extension brace.

The patient was discharged 48 h later without complications. The patient visited the office at 2 wk postoperatively for wound inspection and stitch removal. At 4 wk, he was allowed to initiate proprioceptive weight bearing with crutches. The radiograph showed total consolidation of the fracture at 5 wk postoperatively. At 6 wk, the immobilization device was removed; strengthening exercises of the quadriceps, passive flexion-extension movements to 90º degrees of flexion and limited active flexion-extension movements of the limb (0º to 60º degrees) were initiated; and ambulation with partial weight bearing assisted by a crutch was allowed. At 8 wk, he was allowed to move freely with full weight bearing. At 12 wk, he could perform 130º degrees of flexion and full extension. He was allowed to return to sports activities at 5 mo postoperatively and the patient subjectively report being in excellent condition.

Mayba et al[10] was the first to report this pathology in 1982, and since then, a few case reports and case series have been published. Kaneko et al[11] conducted a review of six cases previously published in the literature. Subsequently, Mosier et al[5] reported 19 cases of TT avulsion fractures, 2 of which were associated with a PT rupture. Yousef et al[12] reported the incidence of a combined injury to the TT and PT to be 4.2% in a retrospective analysis of 71 pediatric cases of injuries of the knee extensor mechanism. We believe the occurrence of such injury patterns has increased progressively due to the increased participation in sports activities at younger ages.

In most cases, the age of presentation was between 11-years-old[13] and 18-years-old[14]. This injury is more common in males than in females and occurs predominantly on the left side[15]. Patients with this pathology tend to have well-developed quadriceps muscles capable of exerting tremendous forces across the extensor mechanism of the knee[16]. The mechanisms of injury for each of the two lesions described in this case report have been well described (vigorous eccentric contraction of the extensor mechanism with the knee fixed in flexion or, as in our case, an aggressive quadriceps contraction when the ipsilateral foot is fixed, both of which can occur during jumping activities)[16]. However, it is not clear why the extensor mechanism fails in two different locations[17]. The synchronous failure at both sites can imply perfectly balanced forces at both sites[15]. Kaneko et al[11] suggested that an eccentric contraction of the quadriceps can initially result in avulsion of the TT, which intensifies to the point of rupture of the PT. When the bony fragment has been inverted while initially remaining attached to the proximal periosteum, there is secondary resistance to the extensor mechanism, and when knee flexion and a forceful quadriceps contraction are maintained, the PT avulses from the TT[14].

Clinical diagnoses of these injuries can be challenging, and the loss of active knee extension should heighten clinical suspicion for associated PT rupture[18]. Radiographically, the presence of patella alta on lateral radiographs of the knee flexed to 30° as well as calcified fragments below the patella may indicate the presence of PT rupture[12,13]. Frankl et al[8] recommended taking plain lateral knee radiographs in extension and flexion, with an increased patellar to tibial distance in flexion indicating a combined injury. Tai et al[19] mentioned that the Insall-Salvati index can be used, which had a value of 1.6 in the preoperative period in their study; however, we used and suggest using the Caton-Deschamps, as it is more reliable and does not involve a measurement of the anterior tibial tuberosity, which may be fragmented or displaced from its original position, biasing the measurement.

The use of advanced imaging can surely increase diagnostic accuracy. MRI is indicated when there is articular involvement of the fracture or the associated lesions of the menisci, articular cartilage, cruciate ligaments or collateral ligaments need to be evaluated[20-23]. However, it is striking that only a small number of cases were assessed by this method preoperatively (6 of 23, 26.08%). Nevertheless, MRI is not available in all hospitals and has a high cost. CT is useful for the evaluation of the articular surface and preoperative planning, but it has the disadvantage of exposing the patient to radiation.

Pandya et al[16] retrospectively determined that these types of injuries are associated with sports that involve jumping (basketball 27%, soccer 22%, and running 22%); however, in our extensive review, we observed that this combined injury also occurs in sports such as wrestling[24], gymnastics[15], hurdling[11], running[12] and handball[19].

Multiple treatment and fixation methods have been proposed, such as the use of immobilization with plaster or percutaneous fixation in the Ogden 1 type fractures and the use of Kirschner wires[8], tension bands[25], staples[26], conventional AO screws[23] or cannulated screws (unicortical or bicortical with and without the use of washers, it has been previously shown that there are no differences regarding the number of cortices)[27] measuring 3.5 mm[3], 4.0 mm[28], 4.5 mm[22], 5.0 mm[17] and 6.5 mm[14] with full or partial thread; usually, two screws are used, but the use of three screws has been described[18]. The reinsertion/fixation of the patellar tendon has been described using direct suture repair of the tendon to the periosteum[14], staples[29], tension bands, transosseous sutures through the tibia in an oblique[3] or horizontal direction[17], pole screws[22], fixing anchors placed in the native footprint of the PT insertion or on each side of the fracture line[30] and combinations of these methods[28]. The preferred suture technique for patellar tendon repair is the Krackow technique for most cases and the Bunell technique for some cases[12], and various suture materials are used: 2/0 Ethindond[31], #2 Fiberwire®[3,17], #2 polydioxanone[18] or Vycril[14]. Due to the rare nature of this pathology, no clinical studies have been performed comparing the previously described methods; however, on the basis of the positive findings reported in most of the studies, we believe that achieving stable fixation of the bone fragment and repair and adequate reinsertion of the patellar tendon can lead to a satisfactory clinical outcome. However, the choice of the method depends on the age of the patient, the size and the comminution status of the fragment, and the surgeon’s experience, based on previous case reports, we suggest as a hypothesis that the absolute fixation of the bone fragment and an adequate repair and reinsertion of the PT by any method lead to satisfactory clinical results.

Similarly, the use of semitendinosus autografts for acute lesions[22] and the use of Achilles tendon allografts for chronic lesions[32] to augment or protect the PT have been previously described (where wire cerclages have also been used[18,19]or high strength sutures[3]). In some cases, surgery is associated with additional procedures, such as releasing the anterolateral compartment of the leg to prevent the appearance of a compartment syndrome or partial meniscectomies. It is noteworthy that in most cases, patients undergo surgery in the acute phase on the same day or the day after diagnosis; however, we believe that the longest time from injury to surgery was presented in our study (6 d) and the study by Garbuz et al[24].

In most studies, pneumatic tourniquets were not used, except for some exceptions[33] in which complications or difficulties with its use were not reported. However, in our case, we preferred not to use a tourniquet due to the possibility of retraction of the PT with its use. Similarly, only a few studies have used postoperative drainage[14,23,30]. In all cases, a vertical midline incision of variable length was preferred for the management of the patients (generally 6 to 10 cm in most studies).

A 180 degree rotation of the bone fragment has been reported in many studies[2,3,11,21,28]. Wu et al[30] mentioned that after 180° of rotation, soft-tissue attachments around the tibial tubercle prevent further displacement, but continued application of a force beyond this angle may then cause a patellar ligament avulsion.

Postoperative recovery protocols in existing case reports range from leg immobilization for 4-8 wk to range of motion exercises being performed early[18]. The exercises start from strengthening exercises in extension, progressive active movements and assisted walking in extension from 3 wk or to the withdrawal of immobilization. The full mobility range (0° to 130°-140°) is generally reached between 12-14 wk postoperatively[33]. The complete recovery of patients with their subsequent return to sports activities has been reported between 5-6 mo postoperatively[33].

Few articles have reported long-term complications or the need for additional procedures for subsequent management or removal of temporary implants[18]. TT avulsion fractures can cause disruption to the growth plate, which can cause skeletal deformities such as genu recurvatum or limb-length discrepancy, which can be present in 4% and 5% of cases, respectively[34]. It is imperative to continue to follow up these patients until they have reached skeletal maturity to ensure normal growth without any resultant osseous deformities, as additional procedures, such as growth plate modulation, may be required[23].

The strengths of this case report include X-ray, CT, and MRI assessment of the injury, accurate description of the surgical techniques and photos of them, detailed postoperative follow-up, and a comprehensive evaluation of all available literature which could help in the elaboration of clinical practice guidelines for this pathology. In Table 1, we present the results for all the 23 previous case reports described since 1982, including the present case report.

| No. | Ref. | Year | Country | Gender | Age | Sport | Mechanism of injury | Approach | Screw diameter | Screw number | Kind of screw | Autograft/ allograft | Method of patellar tendon fixation | Protection | Immobilization | Rehabilitation | Range of motion | Consolidation | Use of MRI |

| 1 | Mayba[10] | 1982 | Canada | Male | 15 | Running | Jump | Anterior | - | 1 | Cortical | - | Sutures | - | Cast | 6 wk | 1 yr | - | No |

| 2 | Frankl et al[8] (Case 1) | 1990 | United States | Male | 16 | Basketball | Jump | Anterior | - | 1 | Cortical | - | Sutures | - | - | - | 6 mo | - | No |

| 3 | Frankl et al[8] (Case 2) | 1990 | United States | Male | 12 | Gymnast | Hyperflexion | Anterior | - | - | - | - | Kirschner wire + suture | - | - | - | 3 mo | - | No |

| 4 | Goodier et al[14] | 1994 | England | Male | 18 | Soccer | Tripped | Anterior | 6.5 | 1 | Cancellous | - | Sutures | - | Cast | 6 wk | 11 wk | - | No |

| 5 | Kaneko et al[11] | 2000 | Japan | Female | 14 | Hurdle | Jump | Anterior | - | 1 | Cancellous | - | Staples | - | Cast | 4 wk | 3 mo | - | No |

| 6 | Sullivan et al[4] | 2000 | Turkey | Male | 14 | Wrestling | Extension | Anterior | - | - | - | - | Staples + Anchors de Ethibond | - | Splint | 4 wk | 6 wk | - | No |

| 7 | Seo et al[34] | 2005 | South Korea | Male | 14 | Jumping rope | Jump | Anterior | - | 1 | Cancellous | - | Staples | - | Cast | 6 wk | 3 mo | - | Yes |

| 8 | Uppal et al[21] | 2007 | United States | Male | - | Running | - | Anterior | - | 1 | Cancellous | - | Transosseous suture | - | Cast | 4 wk | 4 mo | - | No |

| 9 | Swan et al[9] | 2007 | United States | Male | 15 | Basketball | Jump | Anterior | 4.0 | 2 | Half threaded | - | Transosseous suture | - | Knee Immobilizer | Postop | 6 wk | - | Yes |

| 10 | Boyle et al[15] | 2011 | New Zealand | Male | 11 | Gymnast | Jump | Anterior | - | - | - | - | Kirschner wire + suture | Tension wire | Cast | 12 wk | 12 wk | - | Yes |

| 11 | Sié et al[28] | 2011 | Ivory Coast | Male | 15 | - | Jump | Anterior | - | - | - | - | Staples | - | Cast | 6 wk | 6 wk | - | No |

| 12 | Wu et al[32] | 2012 | Taiwan, China | Male | 18 | Basketball | - | Anterior | - | - | - | - | Surgical steel 7.0 + staples + ethibond | - | Splint | - | 3 mo | - | No |

| 13 | Sharief et al[30] | 2015 | Kuwait | Male | 15 | - | Fall | Anterior | 4.0 | 2 | Cancellous | - | Sutures | - | Splint | 4 wk | 2 mo | - | No |

| 14 | Tai et al[19] | 2015 | Hong Kong, China | Male | 16 | Handball | Jump | Anterior | 6.5 y 5.0 | 3 | Cannulated | - | Transosseous suture | Tension wire | Fiberglass | 8 wk | 5 mo | - | No |

| 15 | Gurbuz et al[24] | 2016 | Turkey | Male | 14 | Wrestling | Extension | Anterior | - | - | - | - | Staples + Anchors de Ethibond | - | Splint | 4 wk | 6 wk | - | No |

| 16 | Clarke et al[18] | 2016 | - | Male | 16 | Football | Tackle | Anterior | 4.0 | 3 | Cortical | - | Transosseous suture | Tension wire | - | Postop | 5 mo | - | No |

| 17 | Yousef et al[12] (Case 1) | 2017 | United States | Male | 13 | Basketball | Jump | Anterior | - | 1 | Half threaded | - | Transosseous suture + spiked washer | - | Cast | 3 wk | 12 wk | 12 wk | No |

| 18 | Yousef et al[12] (Case 2) | 2017 | United states | Male | 14 | Basketball | Jump | Anterior | - | 2 | Cannulated | - | Suture anchors | - | Knee Immobilizer | 8 wk | 20 wk | 8 wk | No |

| 19 | Yousef et al[12] (Case 3) | 2017 | United states | Male | 14 | Running | Fall | Anterior | - | 2 | Cannulated | - | Transosseous suture | - | Knee Immobilizer | 4 wk | 12 wk | 8 wk | No |

| 20 | Agarwalla et al[23] | 2018 | United States | Male | 14 | Basketball | Jump | Anterior | 3.5 | 3 | Cortical | - | Anchors | - | Hinged Knee Brace | 3 wk | 5 mo | - | Yes |

| 21 | Pereira et al[22] | 2018 | Brazil | Male | 15 | Basketball | Jump | Anterior | 4.5 | 2 | Cannulated | Semitendinosus | Suture anchors | - | Brace | 6 wk | 14 wk | 14 wk | Yes |

| 22 | Behery et al[2] | 2018 | United States | Female | 13 | Skateboarding | Hyperflexion | Anterior | 3.5 | 2 | Cortical | - | Transosseous suture | - | Knee Immobilizer | 1 wk | 5 mo | - | Yes |

| 23 | Bárcena Tricio et al[3] | 2019 | Spain | Male | 14 | Soccer | Jump | Anterior | 5.0 | 2 | Half threaded | - | Transosseous suture | - | Cast | - | 12 wk | - | No |

| 24 | Morales-Avalos et al (Present Report) | 2020 | Mexico | Male | 16 | Soccer | Extension | Anterior | 3.5 | 1 | Cannulated | - | Suture anchors | - | Knee Immobilizer | 12 wk | 5 mo | 10 wk | Yes |

This case presentation and literature review covers the most relevant clinical, radiographic and treatment details described in the international literature so far, which provide the reader with an overview of this rare condition. Subsequent clinical and biomechanical studies are necessary to determine the definitive etiology of this condition as well as to establish a specific treatment method.

We would like to acknowledge to Dr. Flores FB for recommending modifications to the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, No. 473939.

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ju SQ S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Frey S, Hosalkar H, Cameron DB, Heath A, David Horn B, Ganley TJ. Tibial tuberosity fractures in adolescents. J Child Orthop. 2008;2:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Behery OA, Feder OI, Beutel BG, Godfried DH. Combined Tibial Tubercle Fracture and Patellar Tendon Avulsion: Surgical Technique and Case Report. J Orthop Case Rep. 2018;8:18-22. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Bárcena Tricio VM, Hidalgo Bilbao R. Combined avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle and patellar tendon rupture in adolescents: a case report. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019;29:1359-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sullivan L, Lee CB, Simonian PT. Simultaneous avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle with avulsion of the patellar ligament. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13:156-158. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mosier SM, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Watson-Jones R. Fractures and joint injuries. 5th ed. Baltimore, USA: Williams & Wilkins, 1979: 1048-1050. |

| 7. | Ogden JA, Tross RB, Murphy MJ. Fractures of the tibial tuberosity in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:205-215. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Frankl U, Wasilewski SA, Healy WL. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle with avulsion of the patellar ligament. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1411-1413. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Swan K Jr, Rizio L. Combined avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle and avulsion of the patellar ligament. Orthopedics. 2007;30:571-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mayba II. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle apophysis with avulsion of patellar ligament. J Pediatr Orthop. 1982;2:303-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kaneko K, Miyazaki H, Yamaguchi T. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle with avulsion of the patellar ligament in an adolescent female athlete. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10:144-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yousef MAA. Combined avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle and patellar tendon rupture in pediatric population: case series and review of literature. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28:317-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kramer DE, Chang TL, Miller NH, Sponseller PD. Tibial tubercle fragmentation: a clue to simultaneous patellar ligament avulsion in pediatric tibial tubercle fractures. Orthopedics. 2008;31:501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goodier D, Maffulli N, Good CJ. Tibial tuberosity avulsion associated with patellar tendon avulsion. Acta Orthop Belg. 1994;60:336-338. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Boyle MJ, Dawe CJ. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity with associated proximal patellar ligament avulsion. A case report and literature review. Injury Extra. 2011;42:22-24. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pandya NK, Edmonds EW, Roocroft JH, Mubarak SJ. Tibial tubercle fractures: complications, classification, and the need for intra-articular assessment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32:749-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Perez Carro L. Avulsion of the patellar ligament with combined fracture luxation of the proximal tibial epiphysis: case report and review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Clarke DO, Franklin SA, Wright DE. Avulsion Fracture of the Tibial Tubercle Associated With Patellar Tendon Avulsion. Orthopedics. 2016;39:e561-e564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tai DH, Lee KB, Wong KF. Tibial Tuberosity Avulsion Fracture and Patellar Tendon Avulsion: A Case Report. J Orthop Trauma Rehabilitation. 2016;21:44-47. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bauer T, Milet A, Odent T, Padovani JP, Glorion C. [Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle in adolescents: 22 cases and review of the literature]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91:758-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Uppal R, Lyne ED. Tibial tubercle fracture with avulsion of the patellar ligament: a case report. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2007;36:273-274. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Pereira AL, Faria ÂRV, Campos TVO, Andrade MAP, Silva GMAE. Tibial tubercle fracture associated with distal rupture of the patellar tendon: case report. Rev Bras Ortop. 2018;53:510-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Agarwalla A, Puzzitiello R, Stone AV, Forsythe B. Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Fracture with Multiple Concomitant Injuries in an Adolescent Male Athlete. Case Rep Orthop. 2018;2018:1070628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gurbuz K, Uzun EC, Cirakli A, Ozan F, Duygulu F. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle associated with patellar ligament avulsion in a sporting adolescent. A rare case. J Clin Anal Med. 2016;7:548-550. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schiedts D, Mukisi M, Bastaraud H. [Fractures of the tibial tuberosity associated with avulsion of the patellar ligament in adolescents]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1995;81:635-638. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Sie EJ, Kacou AD, Sery BL, Lambin Y. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle associated with patellar ligament avulsion treated by staples. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2011;8:105-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Arkader A, Schur M, Refakis C, Capraro A, Woon R, Choi P. Unicortical Fixation is Sufficient for Surgical Treatment of Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Fractures in Children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:e18-e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sharief RJ, Jimoh R, Alsaqabi MN. Comminuted tibial tuberosity avulsión fracture associated with avulsión of patellar tendón: A case report. Sky J Med Med Sci. 2015;3:123-127. |

| 29. | Howarth WR, Gottschalk HP, Hosalkar HS. Tibial tubercle fractures in children with intra-articular involvement: surgical tips for technical ease. J Child Orthop. 2011;5:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wu KC, Ding DC. Tibial tubercle fracture with avulsión of patellar ligament. Formos J Musculoskeletal Disord. 2013;4:15-17. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Falconiero RP, Pallis MP. Chronic rupture of a patellar tendon: a technique for reconstruction with Achilles allograft. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:623-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | E Albuquerque RP, Giordano V, Carvalho AC, Puell T, E Albuquerque MI, do Amaral NP. Simultaneous bilateral avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity in a teenager: case report and therapy used. Rev Bras Ortop. 2012;47:381-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Seo S, Kim D, Kim M, Seo J. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity with patellar ligament rupture in an adolescent patient. Arthrosc Orthop Sports Med. 2015;2:48-50. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pretell-Mazzini J, Kelly DM, Sawyer JR, Esteban EM, Spence DD, Warner WC Jr, Beaty JH. Outcomes and Complications of Tibial Tubercle Fractures in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36:440-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |