Published online Jun 18, 2019. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i6.235

Peer-review started: March 19, 2019

First decision: April 15, 2019

Revised: May 9, 2019

Accepted: May 21, 2019

Article in press: May 22, 2019

Published online: June 18, 2019

Processing time: 93 Days and 5.1 Hours

Idiopathic clubfoot is a congenital deformity of multifactorial etiology. The initial treatment is eminently conservative; one of the methods applied is the Functional physiotherapy method (FPM), which includes different approaches: Robert Debré (RD) and Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (SVP) among them. This method is based on manipulations of the foot, bandages, splints and exercises adapted to the motor development of the child aimed to achieve a plantigrade and functional foot. Our hypothesis was that the SVP method could be more efficient than the RD method in correcting deformities, and would decrease the rate of surgeries.

To compare the RD and SVP methods, specifically regarding the improvement accomplished and the frequency of surgery needed to achieve a plantigrade foot.

Retrospective study of 71 idiopathic clubfeet of 46 children born between February 2004 and January 2012, who were evaluated and classified in our hospital according to severity by the Dimeglio-Bensahel scale. We included moderate, severe and very severe feet. Thirty-four feet were treated with the RD method and 37 feet with the SVP method. The outcomes at a minimum of two years were considered as very good (by physiotherapy), good (by percutaneous heel-cord tenotomy), fair (by limited surgery), and poor (by complete surgery).

Complete release was not required in any case; limited posterior release was done in 23 cases (74%) with the RD method and 9 (25%) with the SVP method (P < 0.001). The percutaneous heel-cord tenotomy was done in 2 feet treated with the RD method (7%) and 6 feet (17%) treated with the SVP method (P < 0.001). Six feet in the RD group (19%) and twenty-one feet (58%) in the SVP group did not require any surgery (P < 0.001).

Our study provides evidence of the superiority of the SVP method over the RD method, as a variation of the FPM, for the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot.

Core tip: We have compared the clinical results of the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot in the context of the improvement accomplished and the frequency of surgery needed to achieve a plantigrade foot with two Functional physiotherapy methods: Robert Debré (RD) and Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (SVP). Both approaches managed to avoid complete surgery, which shows that the physiotherapies achieve a more flexible foot, allowing a more conservative surgery. Our data indicate that the SVP method achieves prolonged correction of deformities more efficiently than the RD method; the best advantage of the SVP method over the RD method was the greater number of cases without any surgery.

- Citation: García-González NC, Hodgson-Ravina J, Aguirre-Jaime A. Functional physiotherapy method results for the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. World J Orthop 2019; 10(6): 235-246

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v10/i6/235.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v10.i6.235

Idiopathic clubfoot is a common birth defect that occurs in one per 1,000 births. The etiopathogenesis has been linked to several genes and environmental factors, such as consanguinity of the parents, smoking during pregnancy, maternal age, alcohol consumption, oligohydramnios, among others. Approximately 20% of clubfeet are associated with distal arthrogryposis, myelomeningocele, amniotic bands, or other genetic syndromes, and in some cases with talar vertical. In 80% of cases, the etiology is unknown and are referred to as idiopathic clubfoot, of which almost 25% have family history[1-5]. Children with idiopathic clubfeet may have problems with balance, coordination, gross motor function, strength and agility. Neurological developmental difficulties should also be taken into account at the time of assessment, since knowledge of these conditions could facilitate the management of treatment, and the support needed for the patient and their families. The perception of difficulties in mobility, day-to-day activities, pain and discomfort negatively affect the quality of life. The diagnosis of clubfoot has a negative psychological impact for the parents; therefore, it is important that they receive emotional support, information and education about the pathology[6-10]. Currently, the initial treatment of clubfoot is eminently conservative. Among the best-known conservative methods, we highlight the Ponseti method (PM) and the Functional physiotherapy method (FPM), also called the French method. The PM includes manipulation, serial casting, Achilles tendon tenotomy and foot abduction brace. Several studies have reported that PM achieved the initial correction in a shorter time (3 to 13 castings), and 79%-96% of cases are subjected to tenotomy. Some problems have been reported, which include plaster, the above-knee cast making the perineal hygiene more difficult, the removal of cast making it stressful for the child and parents, skin wounds that can be produced by the cast knife or saw, and even skin burns caused by exothermic reaction[11-14]. The FPM is based on manipulations of the foot, bandages, splints and exercises adapted to the motor development of the child aimed to achieve a plantigrade and functional foot. The treatment is extended after the correction phase (around 3 mo) until the child reaches independent walking. The thermoplastic splints are light and of variable rigidity, easy to place by the parents, have good acceptance by the family and child, allow adequate perineal hygiene, and adapt to the phases of motor development. The FPM provides comprehensive care; it deals with very important aspects such as propioception, coordination, balance, flexibility, muscular reinforcement, resistance, facilitates the acquisition of motor skills, in addition to educating and training parents for the management of the pathology. The different approaches of the FPM[15] have enriched the working context of the different multidisciplinary teams, including Bensahel et al[16] [Robert Debré (RD) method], Seringe et al[17,18] [Saint Vincent de Paul (SVP) method] and Diméglio et al[19] (Montpellier method). However, there is a lack of comparative studies between them. Our hypothesis was that the SVP method could achieve prolonged correction of deformities more efficiently than the RD method and decrease the rate of surgeries. The goal of this study was to compare the clinical results of the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot regarding both the improvement accomplished and the frequency of surgery needed to achieve a plantigrade foot with two FPM: the RD and SVP.

This is a retrospective study of a series of cases of clubfeet (n = 71). The review of the therapeutic outcome was carried out on 46 children born between February 2004 and January 2012 with idiopathic clubfoot. The feet were treated in a public hospital with the RD method (n1 = 34, before 2009) and the SVP method (n2 =37, from 2009). Data were taken from the medical records. The children were between 1 and 45 d old when they began treatment, and had a minimum follow-up of two years. Before starting the treatment, feet were photographed (to observe the conditions of the feet in detail and the sequential progress during the treatment, serving as support of the information obtained with the scale), evaluated and then classified according to the severity based on the Dimeglio-Bensahel scale[20] by physicians or physiotherapists experienced with this rating system. This scale ranges from 0 to 20 points (0, 1-5, 6-10, 11-15 and 16-20, corresponding to normal, benign, moderate, severe, and very severe foot, respectively). This scale is widely used, and has proven to be reliable and re-producible in preceding intra-observer and interobserver studies[21,22]. We included children that were treated in our hospital with moderate, severe and very severe idiopathic clubfoot; those who attended the treatment sessions and complied with good observance of the protocol (these data was reflected in the clinical records through the care control sheet carried out by the physiotherapist responsible for each case), and we excluded those classified as benign or non-idiopathic, those previously treated with another method in other hospitals, and those who did not perform the sessions or did not properly comply with the protocol. The Ethics Committee of the Nuestra Señora de Candelaria University Hospital approved this study.

Trained physiotherapists with over ten years of experience working with the RD method performed the treatment. Our experience with the SVP method started in 2009 after the team received training in Paris.

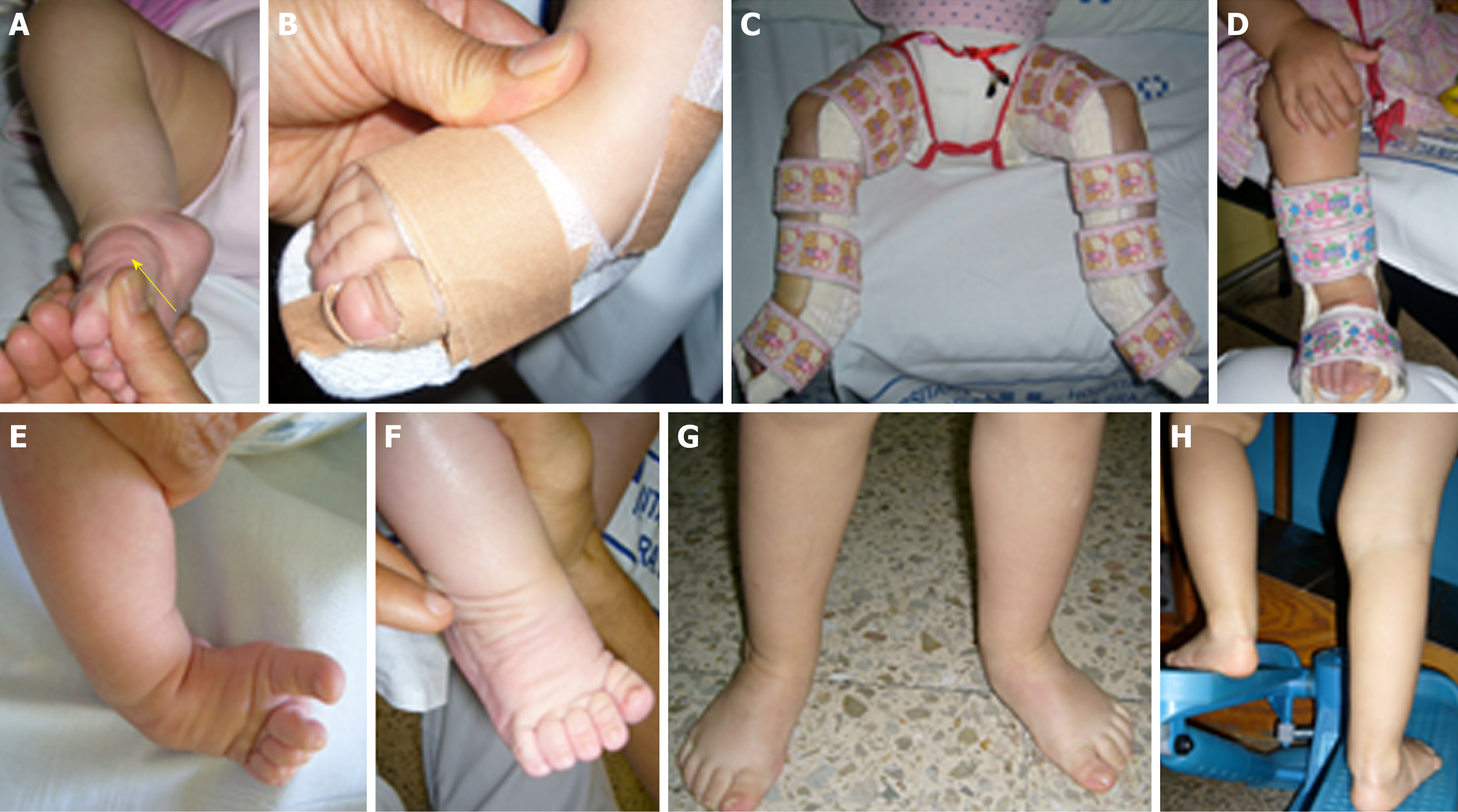

The RD group was treated according to the approach proposed by Bensahel et al[16], and also followed by Souchet el al[23]. We manipulated the foot daily and sequentially, and then applied elastic and nonelastic taping (closing the taping with a cohesive bandage to give greater consistency) between the sessions to maintain the correction obtained, until the pre-standing stage. When the child began to walk, a straight shoe was worn during the day and the Denis-Browne bar at nighttime. After correction of the foot was obtained, the parents continued the stretching, the splinting and exercises daily. The SVP group was treated according to the approach proposed by Seringe et al[17,18] with an additional manipulation for the correction of the cavus, as previously described[11]. This additional manipulation consisted in slightly supinate position with the forefoot moving into its proper alignment with the hindfoot. We manipulated the foot daily and globally, applied an inextensible taping on a rigid plantar plate between the sessions, and then a splint was placed full-time to keep the foot aligned with respect to the leg. The physiotherapist shaped the splint according to the correction achieved and the growth of the child. When the child began to walk, a straight shoe was worn during the day and the short splint during naps, with an above-knee splint overnight. After correction of the foot was achieved, the parents continued the stretching, placing the taping, splinting and exercises daily.

Both interventions were similarly performed. Before starting the treatment, the team explained to the parents the procedure and the care needs. We also stressed that the adhesion of parents to the treatment is a prerequisite for success. Therefore, they were given clear instructions about the use of the splint and the importance of rigorously complying with the protocol. During the sessions, the parents were asked if they complied with the guidelines given and if they experienced any difficulty. The treatment was divided by stages, always adapted to each case: (1) Stage of deformities reduction: the first 3 mo, with physiotherapy daily; (2) Stage of maintenance: from 4th month until pre-standing, with physiotherapy two or three times a week. The parents were trained by the physiotherapist to perform daily stretching, taping, splinting and exercises; and performed these tasks in some sessions in order to check the training; (3) Stage of standing and walking: passive mobilizations, with active physiotherapy one or two times a week, adapted to the motor development of the child (some manipulations and active physiotherapy are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively). In those cases in which we observed a slight adduct of the forefoot when the child walked, a flexible bandage was applied to use with the footwear in order to improve the support and realign the foot with the leg.

The manipulations were performed daily with gentle joint tractions with the child stress-free, each session lasted 30 min per foot and was done by the same ph-ysiotherapist. In each bimonthly consultation, the feet were rated again using the Dimeglio-Bensahel scale[20] in order to objectify the improvement achieved (also, a series of photographs of the feet were taken); a score ≤ 5 was considered good enough, and > 5 not good enough. If at 8 mo of age the treatment was no longer effective, the evolution was considered stabilized and two surgeons evaluated the need for surgery and the optimal time to perform it. In our hospital, it was generally between 10-11 mo old; the surgeon considered that upon re-initiation of ph-ysiotherapy post-surgery, the child would be prepared to stand up, and this contributed to maintaining the correction of the equine of the calcaneus. According to the clinical assessment, we estimated that for the feet that did not exceed 90 degrees ankle dorsiflexion, a percutaneous heel-cord tenotomy was scheduled. When the calcaneus remained elevated with contracture of the posterior soft tissues without reaching 90 degrees of dorsiflexion of the ankle, a limited release was scheduled (Achilles tendon lengthening, with subtalar and tibiotalar capsulotomy). In specific cases, limited surgery could be supplemented with release of the adductor hallucis, and/or plantar fascia through a mini-incision; these were noted as nonrelease surgeries). When the foot was not corrected, and kept triple deformation and stiffness, a complete release (extensive posteromedial release) would be indicated. The surgery was a complementary intervention and was tailored to the specific needs of each case, with an intent to be as conservative as possible. The feet were not X-rayed at the time of revision.

The immobilization was performed with long plaster in knee flexion at 90 degrees for 4-6 wk. At 3 wk, the cast was changed in the operating room under anesthesia to check the correctness achieved, the skin and the scar. The physiotherapy post-surgery was immediately provided to stabilize the correction achieved, including in cases of surgery for recurrence. When the child walked properly, the treatment was considered complete. Then the child was discharged and was controlled each month, then eventually every 3-6 mo, and throughout the growth to detect any functional impairment. If there was any deterioration, it was again referred to physiotherapy. We recommended using the splints up to 4-5 years old, according to severity and evolution.

We could not complete the data for three patients (four feet) because they did not follow the treatment properly for various reasons: three feet in the RD group (two of which developed an allergy to the taping and had to stop the treatment, and one of a child who was changed to another hospital) and one foot in the SVP group also due to a change of residence. Therefore, we did not get considered for the results.

The primary outcome measure was the rate of the severity of deformity by the Dimeglio-Bensahel scale[20]. To get this scoring, the degrees of reducibility of the internal rotation of the calcaneo-forefoot block, the adduction of forefoot relative to hindfoot, the equinus and the varus of the hindfoot were measured using a small goniometer and the charts. These four components can add a maximum of 16 points. It was also taken into account whether the foot presented medial and posterior creases, cavus, and the poor muscle condition (hypertonic, contracture, amyotrophic). Each of these conditions adds one more point. A second outcome measure was the need of complementary surgery to achieve a plantigrade foot. Other data recorded were the affected laterality, gender, and date of birth. To achieve a plantigrade foot, patient outcome were defined as: (1) Very good, when obtained only by phy-siotherapy; (2) Good, complemented by percutaneous heel-cord tenotomy; (3) Fair, complemented by limited release; and (4) Poor, complemented by complete release.

A biomedical statistician performed a statistical review of the study. The sample characteristics were summarized as relative frequencies of their component categories for nominal variables and as median (range) for numerical variables due to its non-normal distribution. Comparisons between treatments were performed with the χ2 tests for nominal variables and the U test for numerical ones. The odds-ratio (OR) analysis was used to determine the relapse rate of the approaches. We observed a 25% success rate (good and very good results) with the RD method; so in order to detect a clinically relevant difference of at least 40% more success with the SVP method, a sample of 31 feet in each treatment group would be required to achieve a study power of 90% in bilateral hypothesis testing with a level of statistical significance P ≤ 0.05. All calculations were carried out using the statistical software package IBM SPSS 24.0® for Windows NT®.

Due to the lack of data from 3 patients (4 feet), the final sample consisted of 67 idiopathic clubfeet from 43 children (29 males and 14 females). Thirty-one feet (46%) were treated with the RD method and thirty-six feet (54%) were treated with the SVP method. The comparison of both groups at baseline is shown in Table 1. Both groups showed homogeneity at baseline for all the considered factors; although the average age of the children in the SVP group was lower, the differences were not statistically significant. The comparison of the improvement achieved by category with RD and SVP groups at 8 mo with respect to baseline is shown in Table 2. It has been found that the percentage of moderate feet that reached normality was lower in the group treated with the RD method (40%) compared to those who were treated with the SVP method (80%); the percentage of severe feet that managed to reclassify as benign was lower in the group treated with the RD method (16.6%) compared to those who were treated with the SVP method (100%); the percentage of very severe feet that managed to reclassify as benign was null in the group treated with the RD method (0%) compared to those who were treated with the SVP method (44.4%). A statistically significant difference was reached P = 0.001. The comparison of the results obtained by category at two years of age for the RD and SVP groups to achieve a plantigrade foot according to the procedure that was necessary is shown in Table 3. It has been seen that only 60% of moderate feet treated with the RD method were corrected with physiotherapy versus 100% of those treated with the SVP method. The 100% of severe feet treated with RD needed limited surgery; while of those treated with SVP, 65% were corrected with physiotherapy and 35% with hell-cord tenotomy. With both methods, all very severe feet required limited surgery. The outcomes were very good for 19% (only physiotherapy), good for 7% (with heel-cord tenotomy), fair for 74% (limited posterior release), and poor for 0% (complete release); and very good for 58% (only physiotherapy), good for 17% (with heel-cord tenotomy), fair for 25% (limited posterior release), and poor for 0% (complete release) for the feet treated with RD and SVP methods, respectively (P < 0.001). In the RD group, surgery was supplemented with release of the adductor hallucis and/or plantar fascia in 11 feet, and in the SVP group it was supplemented only in two feet. Examples of the progression of the clubfeet with the RD and SVP methods are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively.

| Robert Debré group | Saint Vincent de Paul group | P value3 | |

| Number of feet | 31 | 36 | 0.747 |

| Number of feet by gender, boys/girls | 23/8 | 25/11 | 0.667 |

| Number of laterality affected feet, R/L | 16/15 | 20/16 | 0.809 |

| Number of moderate feet1, % | 10 (32) | 10 (28) | 0.782 |

| Number of severe feet1, % | 12 (39) | 17 (47) | 0.782 |

| Number of very severe feet1, % | 9 (29) | 9 (25) | 0.782 |

| Age at start of treatment in d2 | 14 (2-30) | 10 (1-45) | 0.050 |

| Group | Severity at baseline, n (%) | Severity 8 mo after, n (%) | ||

| Normal | Benign | Moderate | ||

| Moderate 10 (32) | 4 (13) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | |

| Robert Debré | Severe 12 (39) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 10 (32) |

| Very severe 9 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (29) | |

| Moderate 10 (28) | 8 (22) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Saint Vincent de Paul | Severe 17 (47) | 0 (0) | 17 (47) | 0 (0) |

| Very severe 9 (25) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 5 (14) | |

| Group | Severity at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| Very good2 | Good3 | Fair4 | Poor5 | ||

| Moderate 10 (32) | 6 (20) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Robert Debré | Severe 12 (39) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (39) | 0 (0) |

| Very severe 9 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (29) | 0 (0) | |

| Moderate 10 (28) | 10 (28) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Saint Vincent de Paul | Severe 17 (47) | 11 (30) | 6 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Very severe 9 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (25) | 0 (0) | |

In the RD group, the relapses occurred between two and three years old in five very severe feet that initially had fair outcomes; these were treated again with physiotherapy, but required another limited surgery. In the SVP group, the relapses occurred at 3 years old in five feet. Four of these feet were initially very severe and one foot was severe. Three of these feet initially had a fair outcome; two feet required another limited surgery, and one foot at the time of review was undergoing physical therapy; and the remaining two feet that initially had good outcomes were rescued with physiotherapy. An OR = 1.20 indicates that the probability of relapse in the RD group is 1.2 times more than in the SVP group. It is shown in Table 4.

| Group | Relapses Yes | Relapses No | Total |

| Saint Vincent de Paul | 5 | 31 | 36 |

| Robert Debré | 5 | 26 | 31 |

| Total | 10 | 31 | 67 |

We compared two approaches of the FPM regarding the improvement accomplished and the frequency of surgery needed to achieve a plantigrade foot. Our data indicate that the SVP method achieved prolonged correction of deformities more efficiently than the RD method, and substantially decreased the rate of surgeries. In this study, we revealed that both approaches managed to avoid complete surgery, which points to the overall effectiveness of the FPM. This shows that the physiotherapy achieved a more flexible foot, allowing a more conservative surgery. This is particularly significant because it has been shown that extensive surgery results in long-term overcorrection, stiffness, pain and osteoarthritis of the foot and ankle; a lesser correction is well-tolerated and easier to treat in adulthood than a hypercorrection[24]. Our major difficulty with the RD method was the failure to satisfactorily correct the equinus of the calcaneus; most children did not keep the feet inside the shoes with the Denis-Browne bar, despite the adjustments made inside the shoes. In these cases, we had to use only a simple taping. The taping was not enough to maintain the correction achieved in the sessions, and this therefore led to a high frequency of surgeries. In the RD group, two moderate feet improved and became benign, but required a limited release at 15 mo of age due to the persistence of the equine ankle; perhaps in this case, an early hell-cord tenotomy could have prevented it, but we thought that it was due to the lack of efficacy of the containment available. With the SVP method, we more effectively maintain the corrections, and this aspect defines its success. Our result was not due to a reflection of experience with the RD method, however the success rate of the SVP was a consequence of the SVP protocol itself. In the first place, the bandage used on the rigid plate has a greater consistency than just a simple bandage; the strips of tape are more effective because we can achieve a better traction over the calcaneus and fix them to the plate. Second, the rigid plate has the advantage of being angled to 20 degrees on the back in order to continue the descent of the calcaneus. Third, the splints we used were very effective to maintain the correction, adapting completely to each foot. Despite frequent checks and the education received by parents, who assured us that they had followed the instructions received, some families reported that they were unable to achieve compliance post-treatment of the splinting, and these were the cases that relapsed. The relapse rates had a negative association with the applied approach. We want to show when the first relapse appeared in each group, and to determine which approach was able to maintain the correction for a longer period. In the recurrent cases that required surgery, the limited surgery was considered the best option at this stage of growth, and also because the physical therapy was able to maintain the foot with degrees of flexibility, allowing us to consider a more conservative surgery. The improvement achieved with the RD method by category was similar to that described by Souchet et al[23] in the evaluation of the results at the end of the conservative treatment. They compared the outcomes of conservative treatment to the at-birth classification, and found that 50% of moderate feet had a reclassification to benign; 100% of severe feet improved and became moderate; the very severe feet improved and 60% became moderate. Our results with the RD group also correlated with those obtained by Van Campenhout et al[25]. In this study, 75% of the cases require an operation in order to achieve a plantigrade foot. Rampal et al[26] report that more than half of the cases treated with the SVP method do not require surgery; we obtained similar results with our SVP group (58% without any surgery). Different teams had compared the results of the FPM with the PM. Richards et al[27] define their good results as plantigrade foot with or without heel-cord tenotomy; they reported good results for 72% of the feet treated with the PM. Although they obtained better results with the PM than with the FPM, the differences did not reach statistical significance. In our SVP group, we found good results in 75% of the feet. The results obtained by Chotel et al[28] with the FPM showed 17% of hell cord tenotomy and 21% of surgeries (correlates with our SVP group, 17% and 21% respectively). However, these authors found that 94% of the feet treated with PM were subjected to hell-cord tenotomy and 16% required surgery. In this study, the difference between FPM and PM was the type of surgery applied, and this was also due to the criterion of surgical indication in each team. They showed that the increase in the ratio of hell-cord tenotomy in the FPM (24%) managed to decrease the ratio of need for surgery (10%). Two studies of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed similar corrections achieved with the PM and the FPM, except for the persistence of the equine of the calcaneus on the feet treated with the FPM[29,30]. We must bear in mind that these feet had not suffered any hell-cord tenotomy at the time of the last MRI study, contrary to the feet treated with the PM, and all feet had been subjected to the hell-cord tenotomy before the last MRI study. There is still controversy as to which method is better, but it has been demonstrated that both methods achieve similar results; the FPM is as effective as the PM, and the differences between them do not reach statistical significance[8,31-33]. Regarding the learning curve of FPM approaches, we want to point out that learning and mastering the necessary skills to successfully apply the method takes time and requires knowledge. Thanks to its repetitive and extensive process, learning and experience are facilitated until reaching the stability that allows maintaining an adequate rhythm of work.

This study has limitations; the change from one treatment method to another resulted in an inherent bias in the techniques, since the onset of the SVP approach concurred with the learning curve of the latter by the physiotherapists. However, this did not appear to affect the comparability of groups, nor to the SVP group. In any case, the bias would have been produced against the SVP method, meaning that if our experience with the SVP protocol had matched the experience gained with the RD method, and if we had applied randomization, this would have generated even better results for the SVP group. Moreover, the rehabilitation department organization did not allow us to perform both treatment protocols simultaneously; for that reason, we carried out a retrospective study. Due to the high rate of surgery required for complete correction of idiopathic clubfoot using the RD method, we discarded the RD method in favor of the SVP method. In conclusion, the SVP method achieves prolonged correction of deformities more efficiently than the RD method; the best advantage of the SVP method is the greater number of cases without any surgeries. The SVP method should be regarded as a clearly beneficial option for the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. Further studies are needed to corroborate or refute our results.

Idiopathic clubfoot is a common birth defect that affects the musculoskeletal system. The initial treatment is conservative. The Functional physiotherapy method (FPM) is based on mani-pulations of the foot, bandages, splints, and exercises adapted to the motor development of the child to achieve a plantigrade and functional foot with the smallest surgical gesture possible. There are different approaches to the same method, but there is a lack of comparative studies between them. This study describes the results obtained with two approaches of this method [Robert Debré (RD) and Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (SVP)] revealing a significant difference in the ratio of surgeries before and after implementing the SVP method

The motivation behind this study was to detect the most effective FPM approach for maintaining corrections and reducing the rate of surgeries. This is very important because it would translate into saving resources, and would determine whether our institution should continue supporting the application of this method. The results of this study can encourage the implementation of FPM for us by other professionals who are seeking to both improve their interventions in clubfoot and reduce the ratio of surgeries.

The objective of this study was to compare two approaches of the FPM (RD and SVP) with regard to the improvement achieved and the frequency of surgery necessary to achieve a plantigrade foot, and to determine if the choice of one method or another would generate a substantial decrease in the rate of surgeries of clubfoot.

A retrospective review of the therapeutic outcome was carried out for a series of 71 idiopathic clubfeet on 46 children born between February 2004 and January 2012. Data were taken from the medical records. The clubfeet were evaluated and classified according to severity by the Dimeglio-Bensahel scale; we included moderate, severe and very severe feet. Thirty-four feet were treated with the RD method, and 37 feet with the SVP method. The outcomes at a minimum of two years were considered as very good (by physiotherapy), good (by percutaneous hell-cord tenotomy), fair (by limited surgery), and poor (by complete surgery). Comparisons between treatments were performed with the χ2 tests for nominal variables, and U test for numerical ones. The OR test was used for relapse rates. A two-tailed P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Complete release was not required in any case; limited posterior release was done in 23 cases (74%) with the RD method and 9 (25%) with the SVP method (P < 0.001). The percutaneous heel-cord tenotomy was done in 2 feet treated with the RD method (7%) and 6 feet (17%) treated with the SVP method (P < 0.001). Six feet in the RD group (19%) and twenty-one feet (58%) in the SVP group did not require any surgery (P < 0.001). The Dimeglio-Bensahel scale is useful for reflecting the severity of the deformity, and for analyzing the results category by category.

Our hypothesis that the SVP method could achieve prolonged correction of deformities more efficiently than the RD method, as well as decrease the rate of surgeries, was confirmed in this study. The best advantage of the SVP method was the greater number of cases without any surgeries. No new methods were proposed in this study, but we would like to highlight that the SVP method is a clearly beneficial option for the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot.

This study helped emphasize the importance controlling the equine of the calcaneus to avoid the need for surgery, and showed the efficacy of the FPM (the physiotherapy achieves a flexible, functional and painless clubfoot, and substantially reduces the need for surgery). The results obtained correlate with the initial severity of the deformity and with the protocol applied. The success of the treatment is based on two basic pillars: the adherence of parents to treatment and team training. It is essential to inform, educate and train the family, accompanied by a follow-up throughout the growth. We believe that it is necessary to carry out a future prospective investigation applying the SVP method with long-term follow-up. It is important to note that the current results obtained by different teams with the FPM correlate with those reported in the literature of the Ponseti method, and their differences do not reach statistical significance.

We thank Mónica Hernández Caraballo, Alicia Quintana Coello, and Maria J. Huertas Clemente for collaborating with the treatment of the children and the fabrication of the first thermoplastic splints, Dianelis Castillo Gort for performing the periodic assessments of children and Dr. Félix Claverie Martín for the help with the English translation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pavone P, Ünver B S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Wang H, Barisic I, Loane M, Addor MC, Bailey LM, Gatt M, Klungsoyr K, Mokoroa O, Nelen V, Neville AJ, O'Mahony M, Pierini A, Rissmann A, Verellen-Dumoulin C, de Walle HEK, Wiesel A, Wisniewska K, de Jong-van den Berg LTW, Dolk H, Khoshnood B, Garne E. Congenital clubfoot in Europe: A population-based study. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Siapkara A, Duncan R. Congenital talipes equinovarus: a review of current management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:995-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gurnett CA, Boehm S, Connolly A, Reimschisel T, Dobbs MB. Impact of congenital talipes equinovarus etiology on treatment outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:498-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Merrill LJ, Gurnett CA, Siegel M, Sonavane S, Dobbs MB. Vascular abnormalities correlate with decreased soft tissue volumes in idiopathic clubfoot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1442-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pavone V, Chisari E, Vescio A, Lucenti L, Sessa G, Testa G. The etiology of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Coppola G, Costantini A, Tedone R, Pasquale S, Elia L, Barbaro MF, d'Addetta I. The impact of the baby's congenital malformation on the mother's psychological well-being: an empirical contribution on the clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32:521-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Karol LA, Jeans KA, Kaipus KA. The Relationship Between Gait, Gross Motor Function, and Parental Perceived Outcome in Children With Clubfeet. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Zapata KA, Karol LA, Jeans KA, Jo CH. Gross Motor Function at 10 Years of Age in Children With Clubfoot Following the French Physical Therapy Method and the Ponseti Technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38:e519-e523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lööf E, Andriesse H, Broström EW, André M, Böhm S, Bölte S. Neurodevelopmental difficulties negatively affect health-related quality of life in children with idiopathic clubfoot. Acta Paediatr. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lööf E, Andriesse H, Broström EW, André M, Bölte S. Neurodevelopmental difficulties in children with idiopathic clubfoot. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Ponseti IV, Smoley EN. The classic: congenital club foot: the results of treatment. 1963. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1133-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ganesan B, Luximon A, Al-Jumaily A, Balasankar SK, Naik GR. Ponseti method in the management of clubfoot under 2 years of age: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Brewster MB, Gupta M, Pattison GT, Dunn-van der Ploeg ID. Ponseti casting: a new soft option. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1512-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hui C, Joughin E, Nettel-Aguirre A, Goldstein S, Harder J, Kiefer G, Parsons D, Brauer C, Howard J. Comparison of cast materials for the treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot using the Ponseti method: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Can J Surg. 2014;57:247-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bergerault F, Fournier J, Bonnard C. Idiopathic congenital clubfoot: Initial treatment. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:S150-S159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bensahel H, Guillaume A, Czukonyi Z, Desgrippes Y. Results of physical therapy for idiopathic clubfoot: a long-term follow-up study. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:189-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Seringe R, Atia R. [Idiopathic congenital club foot: results of functional treatment (269 feet)]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1990;76:490-501. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Seringe R, Chedeville R. Traitement non-chirurgical. Le pied bot varus équin congenital. Cahiers d'enseignement de la SOFCOT, nº43. París: Expansion Scientifique Française 1993; 41-53. |

| 19. | Diméglio A, Bonnet F, Mazeau P, De Rosa V. Orthopaedic treatment and passive motion machine: consequences for the surgical treatment of clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:173-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Diméglio A, Bensahel H, Souchet P, Mazeau P, Bonnet F. Classification of clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1995;4:129-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Flynn JM, Donohoe M, Mackenzie WG. An independent assessment of two clubfoot-classification systems. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | van Mulken JM, Bulstra SK, Hoefnagels NH. Evaluation of the treatment of clubfeet with the Diméglio score. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:642-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Souchet P, Bensahel H, Themar-Noel C, Pennecot G, Csukonyi Z. Functional treatment of clubfoot: a new series of 350 idiopathic clubfeet with long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:189-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Besse JL, Leemrijse T, Thémar-Noël C, Tourné Y; Association Française de Chirurgie du Pied. [Congenital club foot: treatment in childhood, outcome and problems in adulthood]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2006;92:175-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Van Campenhout A, Molenaers G, Moens P, Fabry G. Does functional treatment of idiopathic clubfoot reduce the indication for surgery? Call for a widely accepted rating system. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rampal V, Chamond C, Barthes X, Glorion C, Seringe R, Wicart P. Long-term results of treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot in 187 feet: outcome of the functional "French" method, if necessary completed by soft-tissue release. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33:48-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Richards BS, Faulks S, Rathjen KE, Karol LA, Johnston CE, Jones SA. A comparison of two nonoperative methods of idiopathic clubfoot correction: the Ponseti method and the French functional (physiotherapy) method. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2313-2321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chotel F, Parot R, Seringe R, Berard J, Wicart P. Comparative study: Ponseti method versus French physiotherapy for initial treatment of idiopathic clubfoot deformity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:320-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pirani S, Zeznik L, Hodges D. Magnetic resonance imaging study of the congenital clubfoot treated with the Ponseti method. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:719-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Richards BS, Dempsey M. Magnetic resonance imaging of the congenital clubfoot treated with the French functional (physical therapy) method. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:214-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jeans KA, Erdman AL, Jo CH, Karol LA. A Longitudinal Review of Gait Following Treatment for Idiopathic Clubfoot: Gait Analysis at 2 and 5 Years of Age. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36:565-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | El Batti S, Solla F, Clément JL, Rosello O, Oborocianu I, Chau E, Rampal V. Initial treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot: Prognostic factors. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:1081-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Richards BS, Faulks S, Razi O, Moualeu A, Jo CH. Nonoperatively Corrected Clubfoot at Age 2 Years: Radiographs Are Not Helpful in Predicting Future Relapse. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:155-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |