Published online Feb 18, 2019. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i2.81

Peer-review started: December 23, 2018

First decision: December 30, 2018

Revised: January 11, 2019

Accepted: January 26, 2019

Article in press: January 26, 2019

Published online: February 18, 2019

Processing time: 58 Days and 13.5 Hours

The recent federal ruling to against Affordable Care Act (ACA), specifically the mandate requiring people to buy insurance, has once again brought the healthcare reform debate to the spotlight. The ACA increased the number of insured Americans through the development of subsidized healthcare plans and health insurance exchanges. Insurance-based differences in the rate of upper extremity elective orthopaedic surgery have been described before and after healthcare reform in Massachusetts, where a similar mandate was put into place years before the ACA was passed. However, no comprehensive study has evaluated insurance-based differences of knee elective surgery before and after reform.

To investigate how an individual mandate to purchase health insurance affects rates of knee surgery.

A retrospective review was performed within an orthopaedic surgery department at a tertiary-care, academic medical center in Massachusetts. The rate of elective knee surgery performed before and after the healthcare reform (2005-2006 and 2007-2010, respectively) was calculated. The patients were categorized by insurance type (Commonwealth Care, Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, Workers’ Compensation, TriCare, and Uninsured). Using χ2 testing, differences in rates of surgery between the pre-reform and post-reform period and among insurance subgroups were calculated.

Rate of surgery increased in the post-reform period (pre-reform 8.07% (95%CI: 7.03%-9.11%), post-reform 9.38% (95%CI: 8.74%-10.03%) (P = 0.04) and was statistically significant. When the insurance groups and insurance types were compared, the rates of surgery are not significantly different before or after reform.

The increase in the rate of elective knee surgery in the post-reform period suggests that health care reform in Massachusetts has been successful in decreasing the uninsured population and may increase health care expenditures. This is a hypothesis generating study that suggests further avenues of study on how mandated coverage may change healthcare utilization and cost.

Core tip: We examined how an individual mandate in the United States may affect rates of knee surgery. This topic is of great interest as the United States thinks about moving to a universal coverage model and to countries that already have such a system. We found that the rate of surgery increased after the implementation of mandated universal coverage. Also, we found that patients on lesser reimbursing insurance plans were not discriminated against compared to private insurance plans.

- Citation: Kim D, Do W, Tajmir S, Mahal B, DeAngelis J, Ramappa A. Mandated health insurance increases rates of elective knee surgery. World J Orthop 2019; 10(2): 81-89

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v10/i2/81.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v10.i2.81

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) nationally under the Obama administration in March 2010 stimulated discussion over how the individual mandate and other provisions of the law would affect the utilization and delivery of healthcare. With annual costs of $849 billion a year, orthopaedic care delivery accounts for nearly 7.7% of the GDP, affects 77 million Americans annually, and is an essential component to the successful reformation of United States healthcare[1]. Recently, the ACA was struck down by a federal judge on the grounds that the mandate requiring people to buy health insurance was unconstitutional[2,3]. This ruling has the potential to result to seismic shifts to the healthcare market and brings the debate of healthcare reform back into the spotlight.

In 2007 Massachusetts was the first state to pass a sweeping healthcare reform law. Because its provisions are very similar to the ACA (a universal coverage mandate, a government-run healthcare exchange (Commonwealth Connector), and novel partially-subsidized managed care plans (Commonwealth Care), eyes are once again focused on the Massachusetts as a test case for how ACA will affect the rest of the country. Given the similarities between the Massachusetts law and the ACA, it is very likely that changes in orthopaedic care delivery in post-reform Massachusetts will reflect future changes nationally. One area of particular interest is how much care utilization might change with mandated coverage as the one of the primary costs of healthcare reform is how to control costs.

One important component of these laws is their effect on rate of elective orthopaedic surgery. Previous studies have documented insurance-based differences in rates of elective upper extremity orthopaedic surgery. However, there have been no studies comparing pre- and post-reform rates for knee surgery[4-6]. Given the renewed attention and likely heated debate that will follow this recent ruling, study the Massachusetts experience with mandated coverage is important.

Therefore, we sought to examine a cohort of patients at a single academic orthopaedic practice in Massachusetts to determine if there were insurance-based differences in the rate of elective knee surgery (ROS) pre- and post-reform. We hypothesized that the ROS post-reform would be higher due to increased access and utilization.

Approval for this investigation was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. A retrospective review was performed within the department of orthopedics at a tertiary-care, academic medical center in Massachusetts. The departmental billing database was queried to identify all International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes related to the knee. In an effort to validate the cohort, the ten most common diagnosis codes were identified for two periods in time: Pre-reform (calendar years 2005-2006) and post-reform (calendar years 2007-2010) periods for three orthopaedic surgeons. When compared, the pre- and post-reform ICD-9 codes were found to be identical, suggesting that the spectrum of disease in both periods was similar (Appendix A). These ten diagnosis codes were then used to identify all new patients seen by three surgeons in pre-reform (2005-2006) and post-reform (2007-2010) periods (n = 10420).

Although the healthcare reform was passed on April 12, 2006, the law did not take effect until the beginning of 2007. In keeping with prior investigations, the calendar year 2006 was considered pre-reform[5,6]. To control for confounders, eligible patients were limited to those seeking care from three orthopaedic surgeons with established practices at one academic institution throughout both study periods.

For each patient, age, sex, highest level of education, body mass index (BMI), dates of service, ICD-9 codes, and insurance status at time of presentation were recorded. The billing database contained twenty-one different providers. These different payers were grouped into four insurance groups (uninsured, government, private, Workers’ Compensation) and seven insurance types (Medicaid, Medicare, Worker’s Compensation, private insurance, uninsured, Commonwealth Care, and TriCare) allowed for continuity with previous investigations[5,6].

The ROS was defined as the number of patients who underwent surgery divided by the total number of unique patients in that cohort. For each insurance type at both points in time, the ROS was calculated. In keeping with the method described by McGlaston et al[6], an effect size of greater than or equal to 10% in the rate of surgery was considered clinically significant. An a priori sample size analysis indicated that a 10% difference in the rate of surgery between insurance categories with an α of 0.05 and a β of 0.20 (power = 0.80) could be achieved with 300 persons per insurance category.

The ROS was compared using a Pearson-type χ2 test with Yate’s continuity correction for the entire cohort, each group (uninsured vs government insurance vs private insurance vs Workers’ Compensation) and the seven types of insurance (uninsured vs Commonwealth Care vs Medicare vs Medicaid vs TriCare vs private insurance vs Workers’ Compensation) pre-reform and post-reform. A two-tailed P-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant.

In this study, 2640 patients were enrolled from the pre-reform period and 7780 during the post reform. While gender did not significantly differ between the two study periods, comparison of the cohort’s demographics reveals several disparities (Table 1).

| Pre-reform (n) | (%) | Post-reform (n) | (%) | P-value | ||

| Total | 2640 | 7780 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1551 | 59% | 4419 | 57% | 0.08 | |

| Male | 1089 | 41% | 3361 | 43% | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1592 | 60% | 4997 | 64% | 0.00 | |

| Black | 440 | 17% | 1320 | 17% | 0.72 | |

| Asian | 98 | 4% | 323 | 4% | 0.32 | |

| Hispanic | 208 | 8% | 594 | 8% | 0.69 | |

| Native American | 2 | 0% | 8 | 0% | 0.70 | |

| Other | 114 | 4% | 242 | 3% | 0.00 | |

| Unknown/Unreported | 186 | 7% | 296 | 4% | 0.00 | |

| Highest Education | ||||||

| Unreported | 948 | 36% | 398 | 5% | 0.00 | |

| I did not attend school | 12 | 0% | 41 | 1% | 0.65 | |

| 8th grade or less | 61 | 2% | 215 | 3% | 0.21 | |

| Some high school | 86 | 3% | 341 | 4% | 0.01 | |

| Graduated from high school or GED | 380 | 14% | 1528 | 20% | 0.00 | |

| Some college/vocational/technical pgrm | 222 | 8% | 1033 | 13% | 0.00 | |

| Graduated from college, graduate or post | 692 | 26% | 3192 | 41% | 0.00 | |

| Other | 22 | 1% | 151 | 2% | 0.00 | |

| Patient declined to answer | 133 | 5% | 656 | 8% | 0.00 | |

| Patient unavailable to answer | 84 | 3% | 225 | 3% | 0.47 | |

| BMI | ||||||

| Unreported | 1279 | 48% | 3221 | 41% | 0.00 | |

| Underweight/normal (0-18.49) | 20 | 1% | 42 | 1% | 0.21 | |

| Overweight (18.5-24.9) | 249 | 9% | 947 | 12% | 0.00 | |

| Obese, Class I (25-29.9) | 436 | 17% | 1385 | 18% | 0.13 | |

| Obese, Class II (30-34.9) | 319 | 12% | 1107 | 14% | 0.06 | |

| Obese, Class III (35+) | 337 | 13% | 1078 | 14% | 0.16 | |

| Insurance Type | ||||||

| Uninsured | 199 | 8% | 204 | 3% | 0.00 | |

| Private | 1507 | 57% | 4715 | 61% | 0.00 | |

| Government | 854 | 32% | 2646 | 34% | 0.12 | |

| Workers' compensation | 80 | 3% | 215 | 3% | 0.48 | |

| Insurance sub-types | ||||||

| Medicare | 563 | 21% | 1593 | 20% | 0.35 | |

| Medicaid | 271 | 10% | 694 | 9% | 0.04 | |

| CommCare | 0 | 0% | 240 | 3% | 0.00 | |

| TriCare | 20 | 1% | 119 | 2% | 0.00 | |

| Private | 1507 | 57% | 4715 | 61% | 0.00 | |

| Workers Comp | 80 | 3% | 215 | 3% | 0.48 | |

| Uninsured | 199 | 8% | 204 | 3% | 0.00 | |

Self-reported racial groups demonstrated a significant increase in “White” patients and significant decreases in “Other” and “Unknown/Unreported”. The highest level of education showed a significant increase in all groups except “I did not attend school” and “8th grade or less”. BMI showed a significant increase in “Overweight” and a significant decrease in “Unreported.” The population of uninsured patients dropped significantly post-reform from 8% to 3%, and the population of private insurance increased significantly from 57% to 61%. When divided into insurance subgroups, TriCare subgroup’s increase was statistically significant from 1% to 2% as was Medicaid’s statistically significant decrease post-reform from 10% to 9%. Of note, Commonwealth Care did not exist before the reform.

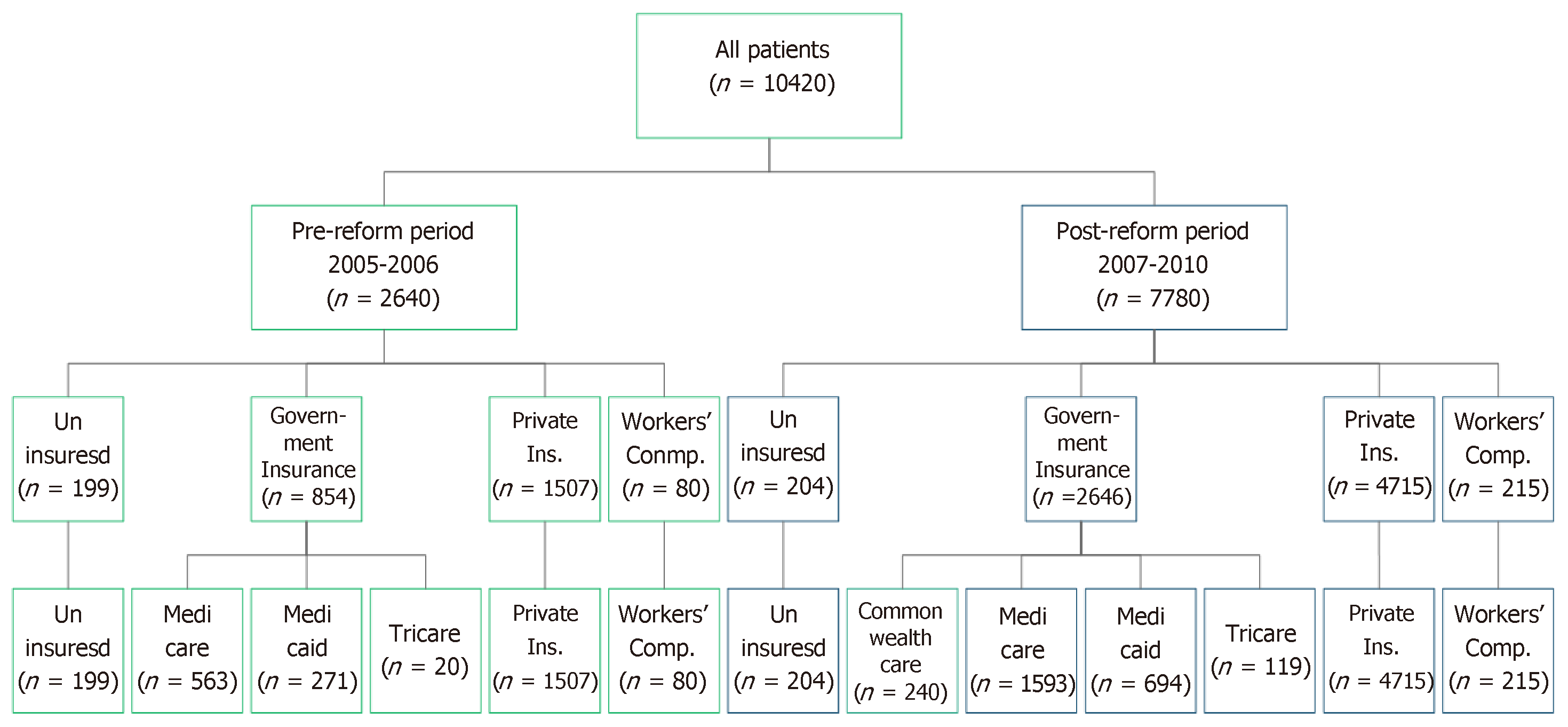

There were 21 different payers present in the patient cohort. These different payers were grouped into four insurance groups (uninsured, government, private, and workers’ compensation) and seven insurance types (Medicaid, Medicare, Worker’s Compensation, private, uninsured, Commonwealth Care, and TriCare). Figure 1 details the distribution of patients in each group.

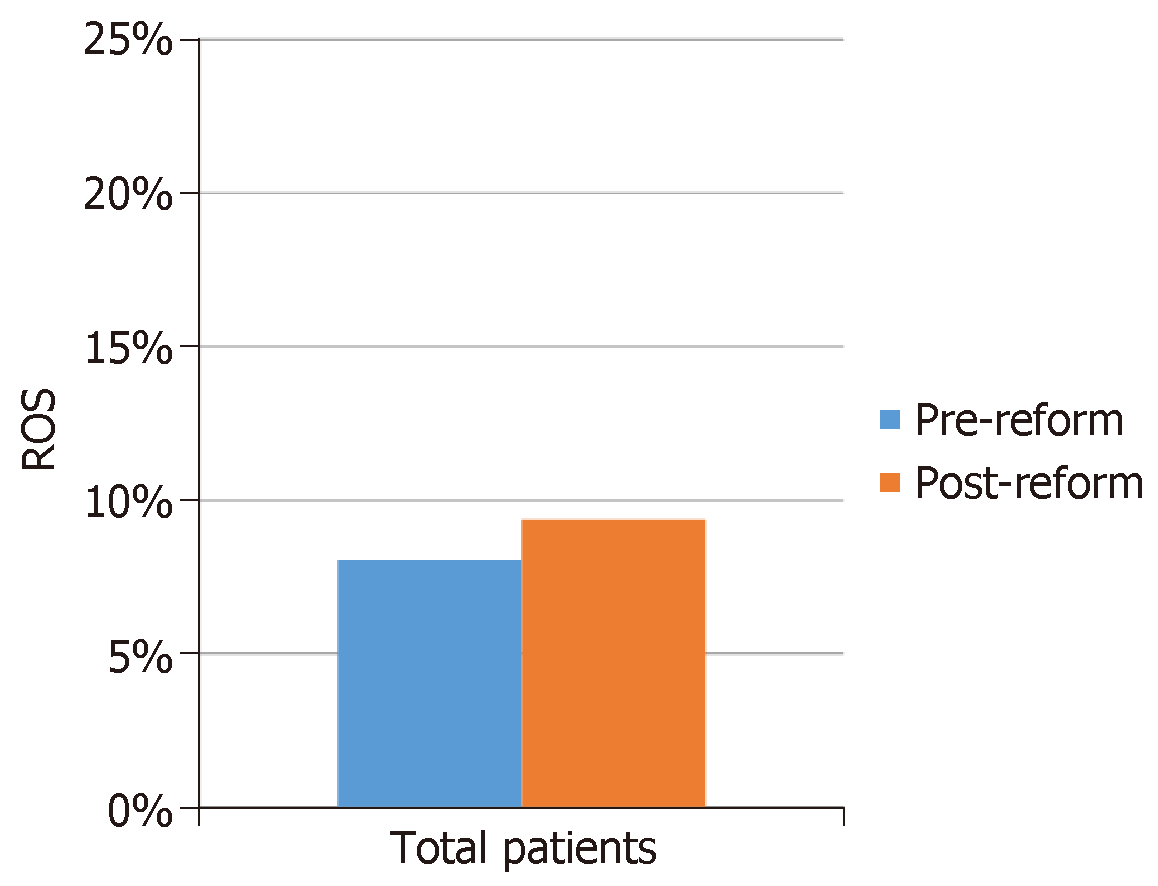

Comparing all-patients pre-reform and post-reform, the pre-reform ROS was 8.07% (95%CI: 7.03%-9.11%) and 9.38% in the post-reform period (95%CI: 8.74%-10.03%; P = 0.04) (Figure 2).

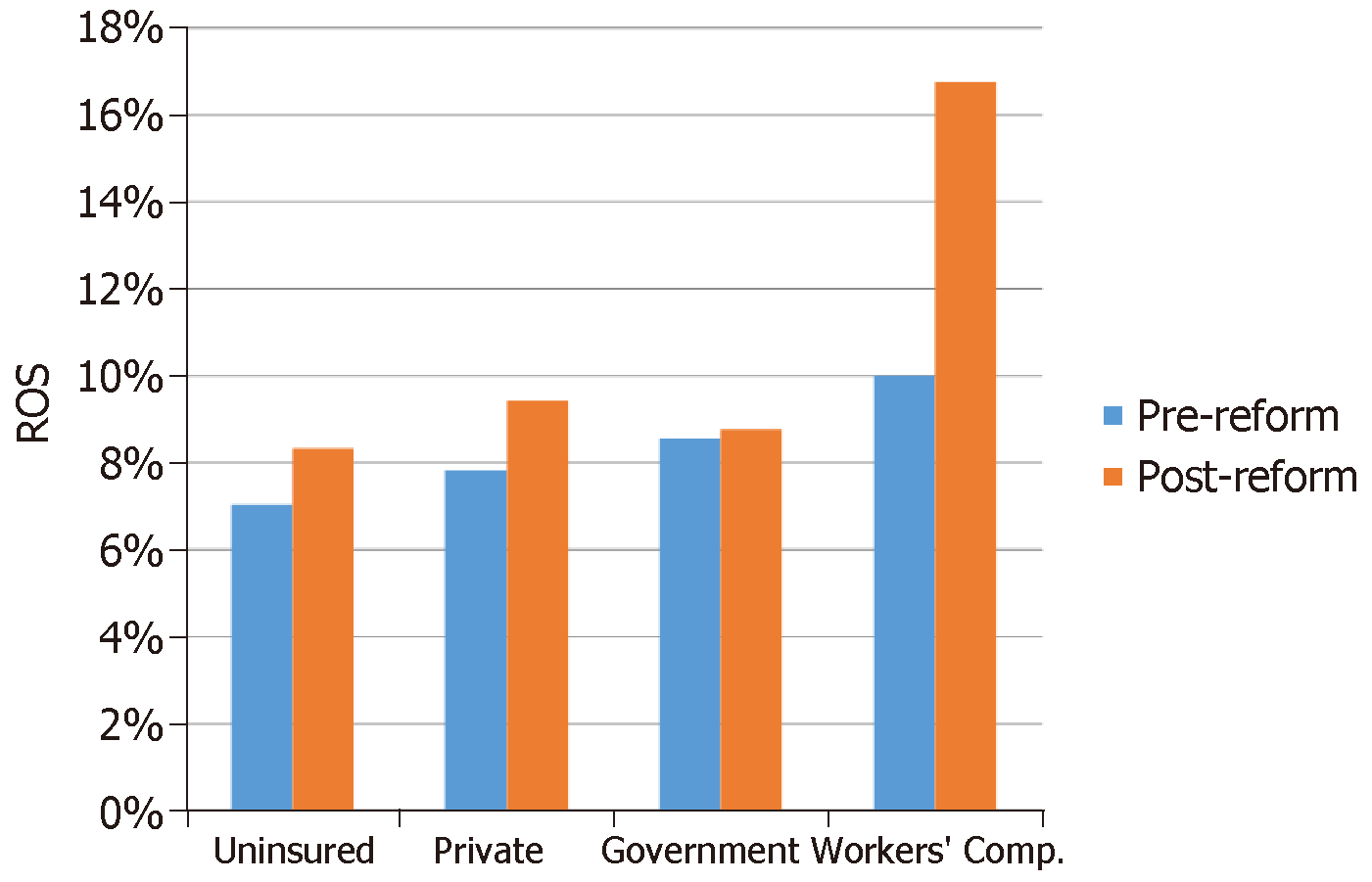

When the groups were compared by their type of insurance (uninsured, private, government-sponsored, and Workers’ Compensation, no significant differences were found before and after healthcare reform (Figure 3).

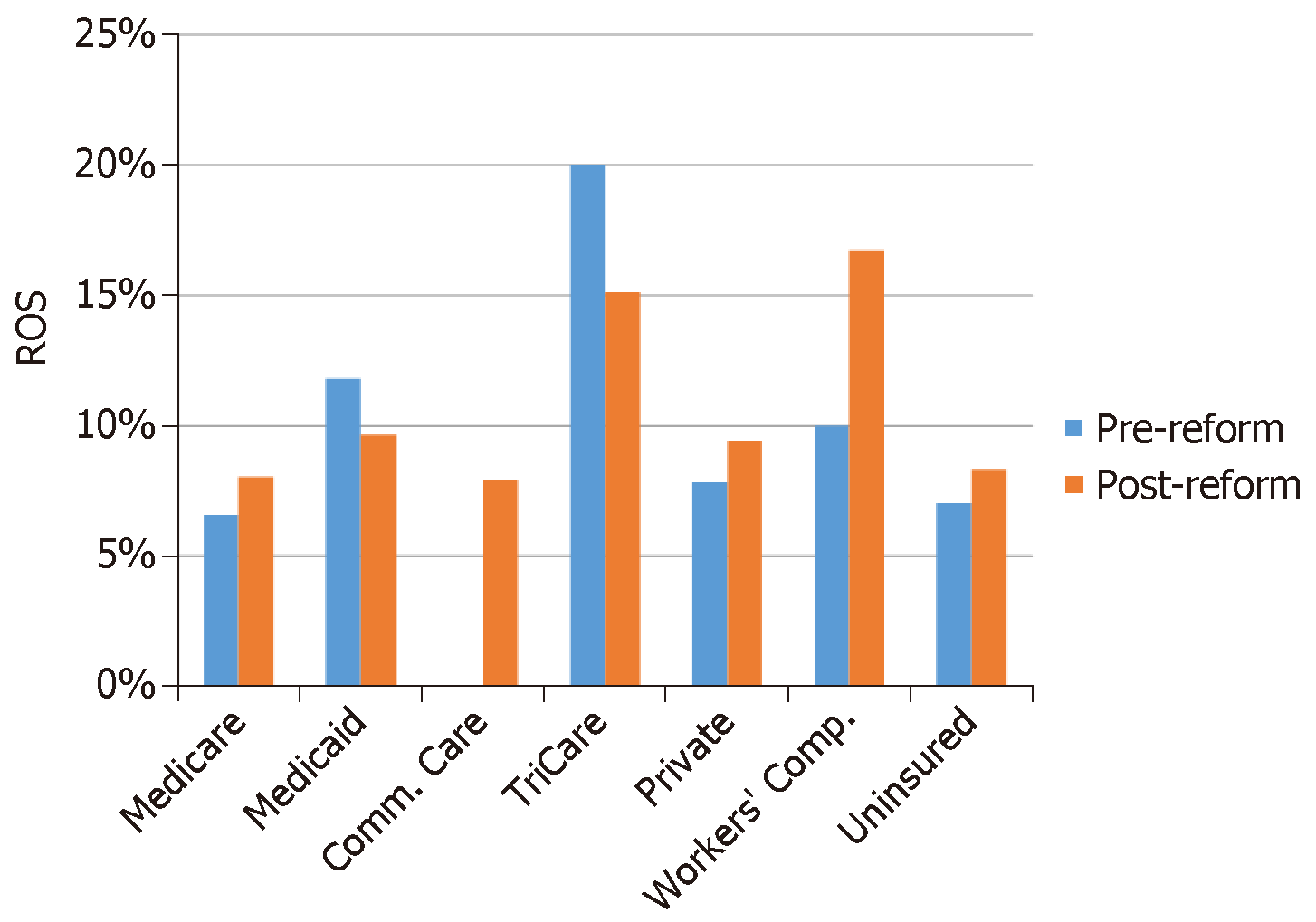

Insurance subgroup analysis further subdivided the patients within the government group into Medicare, Medicaid, TriCare, and Commonwealth Care. Each group’s rate of surgery pre-reform and post-reform was computed and compared using chi-square analysis. Rates of Surgery were as follows: Medicare 6.6% pre-reform and 8.0% post-reform (P = 0.26162); Medicaid 11.8% pre-reform and 9.7% post-reform (P = 0.32167); TriCare 20.0% pre-reform and 15.1% post-reform (P = 0.82471); Private patients’ 7.8% pre-reform and 9.4% post-reform (P = 0.0582); Workers’ Compensation 10.0% pre-reform and 16.7% post-reform (P = 0.2070); and uninsured patients’ 7.0% pre-reform and 8.3% post-reform (P = 0.6249). Rates of surgery across these six groups were not significantly different when compared between the two periods (Figure 4).

This investigation sought to compare the rate of elective knee orthopaedic surgery in a large academic practice before and after healthcare reform in Massachusetts. Given the similarity between the ACA and the mandated coverage stipulated by the Massachusetts law in 2007, this study provides insight into how the rate of elective orthopaedic surgery may change nationally in light of the recent ruling against the ACA and the mandated coverage requirement. It is hypothesis generating and suggests avenues for further research into mandated coverage within Massachusetts and nationally.

Comparing the overall rate of surgery during the pre- and post-reform periods, there was a significant increase in the ROS following mandated coverage. When the cohort is examined by insurance group (uninsured, government, private, Workers’ Compensation), there is no difference in ROS (Figure 3). Similarly, when the individual insurance types (Medicaid, Medicare, Worker’s Compensation, private insurance, uninsured, Commonwealth Care, and TriCare) are considered, the ROS before and after reform remains unchanged (Figure 4).

This finding suggests that with increased insurance coverage (near-universal), patients enjoy increased access to medical services, and, in turn, there may be a higher ROS for musculoskeletal problems. This explanation assumes that there are patients without insurance with operative diagnoses that are now becoming surgical candidates because they are insured. This idea is supported by a significant decrease in the number of uninsured patients. It is possible that a musculoskeletal problem, which was neglected while a patient was uninsured, might require a surgery once they have coverage.

The absence of a statistically significant difference in the ROS in both insurance group and insurance type before and after reform is mostly likely due to the limited size of this investigation. From the a priori sample size analysis, each subgroup would require 300 individuals in order to identify a 10% change in the ROS. Despite starting with more than 10000 eligible patients, many of the subgroups (both insurance groups and type) had less than the recommended 300 individuals participating. Specifically, in the four sub-group analysis, the Workers’ Compensation and uninsured categories were underpowered. In the seven sub-group analysis, all groups were underpowered, except the Medicare insurance group.

The overall comparison of ROS is interesting given that the post-reform period had a significantly higher number of elective surgeries performed. This change may be due to greater access to surgery with the mandated insurance coverage. In this sense, the post-reform period has captured previously uninsured people who would have otherwise not had an elective procedure. However, it is difficult to assess whether a previously uninsured person obtained insurance and then had an elective procedure they would have formerly forgone. Similarly, another potential confound is how physician behavior may have changed in response to mandated coverage. Hypothetically, if government-supported plans offer lower reimbursement, it is possible that the fee change might influence a surgeon’s willingness to operate. While this effect was not studied implicity, the data suggest that such an effect is unlikely because private and subsided plans had similar rates of surgery. In this way, these data support the argument that obtaining health insurance is helpful in decreasing healthcare disparities in orthopaedics, a finding that has been described in elective upper extremity surgery[6]. While this investigation was performed within an academic center, physician remuneration in this practice is based on cash collections, not relative value units or a productivity metric. As a result, the financial benefit associated with surgical treatment and fostering a better payer mix do not appear to have influenced physician behavior.

In Massachusetts, healthcare reform has been deemed a success because the number of uninsured people has decreased. The uninsured rate in Massachusetts has fallen from 10.9% in 2006 to 5.5% in 2007 (US average: 17.1% in 2006 and 16.6% in 2007)[7]. In the practice studied, the drop in uninsured patients was equally impressive, declining from 8% in the pre-reform period to 3% post-reform. However, the system has struggled to contain cost.

The price of health care in Massachusetts despite reform is concerning[8,9]. In May 2012 the non-partisan Kaiser Family Foundation Executive Summary found that since the law’s enactment, the Commonwealth is struggling with rising health care costs. Per capita spending is 15% higher than the national average and Massachusetts continues to have the highest individual premiums in the country[10]. Furthermore, per capita health care spending increased from $8002 in 2006 to $9278 in 2009, 36% higher than the national average $6815[10].

Because the ROS increased in the post-reform period, it is possible that mandated coverage in Massachusetts leads to rising costs in a time when national health care spending has leveled off for the first time in over a decade[7,11]. While the reasons behind the slowdown in national health care spending are hotly debated, there is no question that cost containment is a priority and drives the health care debate today.

To strengthen this analysis, the entire cohort of patient was selected for the specified diagnoses to minimize selection bias. The sample size provided sufficient statistical power for a comparative analysis. As a single-institution, potentially confounding site-specific and geographic variables were avoided. However, as a retrospective review, this study has its limitations. Certain insurance subgroups included fewer than 300 persons, increasing the probability of a type II error. This highlights an inherent challenge in studying groups that constitute a relatively small proportion of the overall population. While performing subgroup analysis may reduce statistical power, it should not be avoided, as previous work has shown that insurance-based differences in operative rates are subtle and may be masked by the method of insurance stratification[5,6]. Future studies of larger cohorts may address this issue. Generalizability may be an issue if orthopaedic care differs from institution to institution.

At baseline, there were some differences in the two cohorts. Among self-reported race, education, and BMI groups, there were statistically significant disparities. In the pre-reform period, the data had a higher chance of being unknown for a given group when compared to the post-reform period. This leads to significant increases within the individual categories while decreasing the unreported or unknown category. Whether the significant increase in the white racial group was due to a true demographic change or improved reporting is unclear. The highest reported level of education experienced a similar pattern. In the pre-reform period, 36% of patients did not report their highest level of education compared with the 5% post-reform did not. This difference may have led to the statistically significant increases in all education categories seen in the post-reform period. Interestingly, BMI also experienced a decrease in the unreported fraction from 48% to 41%. This change resulted in a statistically significant increase from 9% to 12%.

Despite its limitations, this investigation offers several avenues for future study. A more comprehensive evaluation of orthopaedic practices before and after the enactment of health care reform laws in Massachusetts would enable further clarification of the effect of mandated coverage on health care spending. The statistically significant increase in rate of elective orthopaedic knee surgery in the post-reform period suggests that health care reform in Massachusetts, while successful in decreasing the uninsured population, may result in health care expenditures. In turn, higher utilization requires more careful examination. While the rate of surgery may be an imperfect proxy for cost, mandated coverage could result in increased health care spending by increasing the availability of medical services.

Our study is timely given the recent federal ruling against the Affordable Care Act (ACA), specifically the mandate requiring people to buy insurance. The ACA increased the number of insured Americans through the development of subsidized healthcare plans and health insurance exchanges. Healthcare reform was enacted in Massachusetts, where a similar mandate was put into place years before the ACA was passed. We use this opportunity to describe differences in rates of surgery before and after the implementation of the mandate to purchase insurance after healthcare reform.

We answer the key question of whether healthcare reform and the individual mandate increases the rate of knee surgery. Healthcare cost and healthcare reform are the key questions facing the medical field today. How physicians can deliver quality care without exorbitant costs is of interest to many around the world. This hypothesis generating study provides strong impetus to further examine the effects of healthcare reform on other health services.

The main objective was to determine if healthcare reform had an effect on the rate of knee surgery in the state of Massachusetts. The significance of realizing this research is a greater impetus to study healthcare reform and how it may reflect healthcare costs going forward. This is of great interest to every nation in the world.

A retrospective review was performed within the department of orthopedics at a tertiary-care, academic medical center in Massachusetts. The departmental billing database was queried to identify all International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes related to the knee. These ten diagnosis codes were then used to identify all new patients seen by three surgeons in pre-reform (2005-2006) and post-reform (2007-2010) periods (n = 10420). The rate of surgery was defined as the number of patients who underwent surgery divided by the total number of unique patients in that cohort. For each insurance type at both points in time, the rate of elective knee surgery (ROS) was calculated. The ROS was compared using a Pearson-type χ2 test with Yate’s continuity correction for the entire cohort, each group (uninsured vs government insurance vs private insurance vs Workers’ Compensation) and the seven types of insurance (uninsured vs Commonwealth Care vs Medicare vs Medicaid vs TriCare vs private insurance vs Workers’ Compensation) pre-reform and post-reform. A two-tailed p-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant.

Comparing the overall rate of surgery during the pre- and post-reform periods, there was a significant increase in the ROS following mandated coverage. This finding suggests that with increased insurance coverage (near-universal), patients enjoy increased access to medical services, and, in turn, there may be a higher ROS for musculoskeletal problems. Because the ROS increased in the post-reform period, it is possible that mandated coverage in Massachusetts leads to rising costs in a time when national health care spending has leveled off for the first time in over a decade. Given the limitations of our study, a study to better examine the relationship between healthcare reform and costs should be considered.

Healthcare reform and a mandate to purchase health insurance increase the rate of knee surgery. It suggests that having a mandate to buy insurance will lead to increased healthcare costs as patients who now have insurance will utilize more care. Healthcare reform and the individual mandate lead to high rates of knee surgery. As above, healthcare reform and the individual mandate lead to high rates of knee surgery. Healthcare costs increase as more people obtain insurance. The main difference in our study was that we controlled for surgeon number. Other studies can be confounded increasing or decreasing number of providers. We were able to analyze rates of surgery across three surgeons before and after healthcare reform, keeping one of the largest confounders constant. As noted above, healthcare reform and a mandate to purchase health insurance increases the rate of knee surgery. Rates of healthcare utilization are higher in places that have a greater proportion of insured patients as they utilize more healthcare services.

Healthcare reform should be pursued carefully as policies to increase access may also increase costs which may not be desired. A study to examine how other procedures and healthcare service utilization changed with healthcare reform. A similar study can be done for other types of procedures assuming appropriate sample size and ability to collect key information such as rates of procedure done before and after healthcare reform. It would be interesting to do in Massachusetts but also on a national level.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Angoules A, Elgafy H, Emara KM, Ohishi T, Papachristou G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | AAOS. Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States: Prevalence, Societal and Economic Cost. Amer Academy of Orthopaedic, 2008. Available from: https://www.boneandjointburden.org/docs/The%20Burden%20of%20Musculoskeletal%20Diseases%20in%20the%20United%20States%20(BMUS)%202nd%20Edition%20(2011).pdf. |

| 2. | Time. A Judge Ruled Obamacare is Unconstitutional, Here’s How it Could Impact Your Health Insurance. Dec 18, 2018. Available from: http://time.com/5482004/affordable-care-act-court-ruling/. |

| 3. | Goodnough A, Pear R. Texas Judge Strikes Down Obama’s Affordable Care Act as Unconstitutional. Dec 14, 2018. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/health/obamacare-unconstitutional-texas-judge.html. |

| 4. | Brinker MR, O'Connor DP, Pierce P, Spears JW. Payer type has little effect on operative rate and surgeons' work intensity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gundle KR, McGlaston TJ, Ramappa AJ. Effect of insurance status on the rate of surgery following a meniscal tear. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2452-2456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McGlaston TJ, Kim DW, Schrodel P, Deangelis JP, Ramappa AJ. Few insurance-based differences in upper extremity elective surgery rates after healthcare reform. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1917-1924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ryu AJ, Gibson TB, McKellar MR, Chernew ME. The slowdown in health care spending in 2009-11 reflected factors other than the weak economy and thus may persist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:835-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bigby J. Controlling health care costs in Massachusetts after health care reform: there is no silver bullet. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1833-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Long SK, Stockley K, Dahlen H. Massachusetts health reforms: uninsurance remains low, self-reported health status improves as state prepares to tackle costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:444-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaiser Family Foundation. Massachusetts Health Care Reform: Six Years Later. 2012. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/massachusetts-health-care-reform-six-years-later/. |

| 11. | Cutler DM, Sahni NR. If slow rate of health care spending growth persists, projections may be off by $770 billion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:841-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |