Published online Oct 18, 2019. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i10.356

Peer-review started: April 4, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: September 3, 2019

Accepted: September 15, 2019

Article in press: September 15, 2019

Published online: October 18, 2019

Processing time: 204 Days and 16.5 Hours

The usual treatment of septic shoulder arthritis consists of arthroscopic or open lavage and debridement. However, in patients with advanced osteoarthritic changes and/or massive rotator cuff tendon tears, infection eradication can be challenging to achieve and the functional outcome is often not satisfying even after successful infection eradication. In such cases a two-stage approach with initial resection of the native infected articular surfaces, implantation of a cement spacer before final treatment with a total shoulder arthroplasty in a second stage is gaining popularity in recent years with the data in literature however being still limited.

To evaluate the results of a short interval two-stage arthroplasty approach for septic arthritis with concomitant advanced degenerative changes of the shoulder joint.

We retrospectively included five consecutive patients over a five-year period and evaluated the therapeutic management and the clinical outcome assessed by disability of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) score and subjective shoulder value (SSV). All procedures were performed through a deltopectoral approach and consisted in a debridement and synovectomy, articular surface resection and insertion of a custom made antibiotic enriched cement spacer. Shoulder arthroplasty was performed in a second stage.

Mean age was 61 years (range, 47-70 years). Four patients had previous surgeries ahead of the septic arthritis. All patients had a surgical debridement ahead of the index procedure. Mean follow-up was 13 mo (range, 6-24 mo). Persistent microbiological infection was confirmed in all five cases at the time of the first stage of the procedure. The shoulder arthroplasties were performed 6 to 12 wk after insertion of the antibiotic-loaded spacer. There were two hemi and three reverse shoulder arthroplasties. Infection was successfully eradicated in all patients. The clinical outcome was satisfactory with a mean DASH score and SSV of 18.4 points and 70% respectively.

Short interval two-stage approach for septic shoulder arthritis is an effective treatment option. It should nonetheless be reserved for selected patients with advanced disease in which lavage and debridement have failed.

Core tip: Shoulder septic arthritis associated with advanced osteoarthritic changes and/or rotator cuff tendon tears is challenging to treat. The classic approach of lavage and debridement is burdened by a higher failure rate with insufficient eradication of the infection and unsatisfactory functional outcomes. A two-stage approach with initial resection of the articular surfaces, implantation of an antibiotic enriched cement spacer before final treatment with a total shoulder arthroplasty is an appealing therapeutic option. Our retrospective case-series of five patients reveals that this approach is effective to eradicate infection and provides a satisfactory clinical outcome.

- Citation: Goetti P, Gallusser N, Antoniadis A, Wernly D, Vauclair F, Borens O. Advanced septic arthritis of the shoulder treated by a two-stage arthroplasty. World J Orthop 2019; 10(10): 356-363

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v10/i10/356.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v10.i10.356

The shoulder represents the third most common location for septic arthritis in adults[1]. Primary management consists of arthroscopic or open irrigation and debridement and is usually combined with local and systemic antibiotherapy to eradicate the infection. Even after successful elimination of bacteria, cartilage and bone destruction is the consequence of prolonged inflammatory arthritis mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines[2-6]. Early, aggressive treatment is crucial in order to alleviate pain and restore optimal function[7].

When dealing however with a degenerative joint with advanced osteoarthritis, irreparable or massive rotator cuff tears or in presence of endocutaneous fistulas, this classic approach is burdened by a higher failure rate with insufficient eradication of the infection and unsatisfactory functional outcomes. A recent review on shoulder septic arthritis from 2018 reported a 28% revision rate (mean age of 63.9 years), and a 21% complication rate (mean age of 63.7 years) after primary debridement[1]. In the recent years, several authors reported promising results using a two-stage approach to arthroplasty in infected osteoarthritic knees[8,9]. The main advantage of this novel approach is that by treating the underlying bony pathology in terms of resecting the arthritic bone the chances of successful infection eradication are increased and at the same time it allows for adequate pain control and improvement of functional outcomes.

Unfortunately, the evidence in the literature regarding this treatment approach is limited and the outcome of patients with native advanced septic arthritis is merged in published cohorts of infected total shoulder arthroplasties[10-15]. The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the results of a short interval two-stage arthroplasty approach for septic arthritis with concomitant advanced degenerative changes of the shoulder joint.

We retrospectively reviewed our institutions database between January 2012 and December 2017. We included five consecutive patients treated by a two-stage arthroplasty for advanced shoulder septic arthritis. The mean age in our case-series was 61 years (range, 47-70 years). Four of the five patients had undergone previous surgeries on their shoulders (open reduction and plate osteosynthesis of the proximal humerus in 2 cases, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in 2 cases), while one patient presented a primary septic arthritis (Table 1). Mean follow-up was 36.8 mo (range, 12-59 mo). Deep infection was documented in all five cases at the time of initial debridement. All patients had positive cultures from articular puncture and had their follow-up at our institution. There was no exclusion.

| Case | Gender | Age(yr) | Microbiology at thetime of debridement | Previous surgeries to the index procedure |

| 1 | Female | 59 | Streptococcus pyogenes | Open debridement |

| 2 | Male | 69 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (2 times), open debridement |

| 3 | Male | 47 | Cutibacterium acnes | Proximal humerus fracture plate osteosynthesis, open debridement (5 times) |

| 4 | Male | 60 | Cutibacterium acnes | Proximal humerus fracture plate osteosynthesis |

| 5 | Male | 70 | Streptococcus anginosus | Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair |

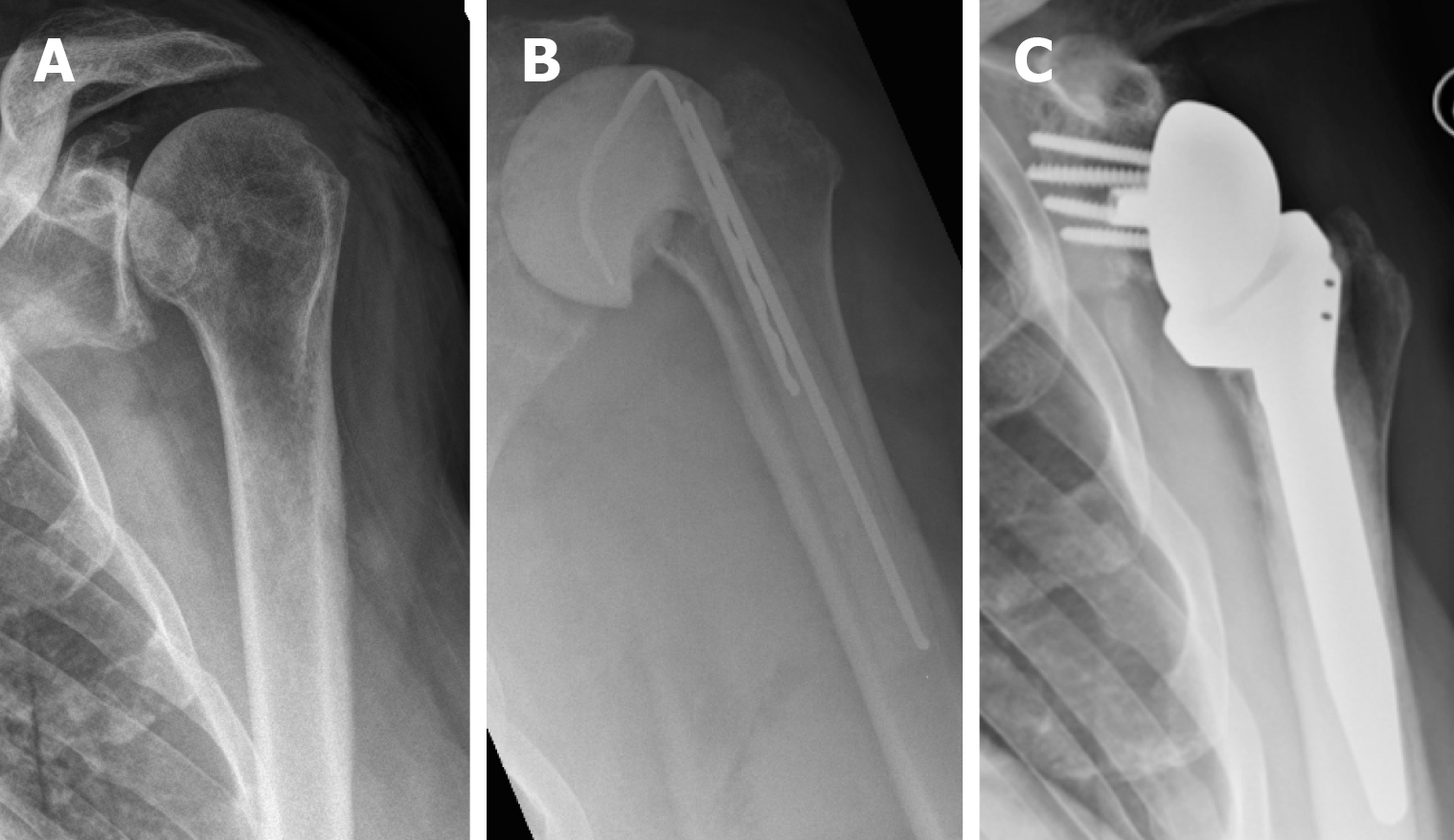

A standard deltopectoral approach was used in all cases. An extensive debridement and synovectomy were performed taking care to remove any devitalized soft-tissue or bone. Similarly to revision arthroplasty due to infection, at least five tissue samples or more were collected for microbiology. With a low-pressure irrigation device, a minimum of nine-liter physiological solution was used to wash out the joint. Free-hand bone cuts were made taking care to remove any bone cysts or foreign bodies in the humeral head. The medullary canal was then opened and reamed to remove any sclerotic tissue. A custom-made cement spacer was molded intra-operatively and loaded with 4 g of Vancomycine and 1, 2 g of Tobramycine per bag of 40 g of Palacos® cement (containing 0.5 g of Gentamycine) (Figure 1). An intra-articular suction drain was placed through the subacromial space at time of closure. Patients were allowed to actively move the shoulder starting day one after surgery. A 2 wk parenteral antibiotherapy was administered according to preoperative and peroperative cultures and in conjunction with a musculoskeletal infectious disease consultant. The type of arthroplasty was adapted to each situation and was performed in a standard manner during a second stage procedure after a mean interval of 6 wk (range, 6-12 wk) (Figure 2).

Absence of persistent infection was based on normalized laboratory markers [C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell counts] and absence of clinical signs of infections. An articular puncture was not performed before second stage, but the spacer and several deep tissue samples were collected for microbiology. Oral antibiotics were maintained for a 3 mo period beginning at the first-stage procedure.

Digital patient’s files were screened for residual pain using the visual analogue scale, range of motion and post-operative complications (including hematoma, seroma, blood transfusion, deep venous thrombosis, and revision surgeries). Biologic outcome was based on dosage of the CRP and the X-rays at last follow-up were evaluated for signs of persistent infection (including osteolysis, bone apposition, and component loosening). Pain was assessed using the visual analogue scale. We further recorded shoulder range of motion (ROM), disability of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) score and subjective shoulder value at last follow-up.

The mean intraoperative blood loss was 880 mL (range, 200-2000 mL) for first stage (debridement and spacer) and 717 mL (range, 218-1800) for the second stage (arthroplasty). The average operation duration, defined as the time past from incision to the end of suturing was 106 min (range, 67-132 min) for the first stage and 115 min (range, 60-174 min) for the second stage. One patient was required to stay in the intermediate care unit for 1 night postoperatively before being transferred to the surgical ward. None of the patients had to be transferred to the intensive care unit postoperatively.

Several complications of glenohumeral septic arthritis could be noted before the first stage of our treatment. Patients number 3 and 4 had draining skin fistulas, patient number five had developed a septic thrombosis of the humeral vein. The shoulder prostheses were implanted 6 wk after the first stage in 4 cases and with an interval of 12 wk in one case. There were two hemi and three reverse shoulder arthroplasties. No intraoperative or postoperative complications were noted.

At final follow-up mean elevation in our series was 102 degrees (range, 70-130 degrees), external rotation was 25 degrees (range, 10-45 degrees). The mean subjective shoulder value was 70% (range, 40%-95%) and DASH score was 18.4 points (range, 7.5-40 points). Detailed results are presented in Table 2. Furthermore, none of them had clinical, biological or radiological signs of persistent infection at last follow-up and therefore considered cured from infection.

| Case | Spacer (wk) | HA/RTSA | Follow-up (mo) | VAS | Elevation | External rotation | CRP | DASH score | SSV |

| 1 | 12 | HA | 59 | 0 | 90° | 30° | 1 | 9.2 | 95 |

| 2 | 6 | RTSA | 46 | 0 | 130° | 20° | NA | 10.8 | 90 |

| 3 | 6 | HA | 53 | 1 | 70° | 15° | 8 | 26.7 | 45 |

| 4 | 6 | RTSA | 14 | 1 | 100° | 10° | 5 | 40 | 40 |

| 5 | 6 | RTSA | 12 | 2 | 120° | 45° | 3 | 7.5 | 80 |

Septic arthritis of the glenohumeral joint is a relatively rare entity representing 3% to 15% of septic arthritis. It can nonetheless lead to major complications such as bone and cartilage destruction if treatment is delayed[7,16-18]. Early treatment is therefore mandatory to alleviate pain and restore optimal function. Open or arthroscopic irrigation and debridement associated with targeted intravenous antibiotic therapy is effective to eradicate the infection[1,18,19]. While arthroscopic procedure seems to lead to better forward flexion and less persistent postoperative pain than open surgery[1,7,20], the number of required procedures is higher and increases further with the severity of infection[21-23].

Functional results after arthroscopic irrigation and debridement are inferior for patients with delayed diagnosis or treatment, as for those with associated rotator cuff tears[22]. Several authors recently reported encouraging results using a two-stage approach to arthroplasty in osteoarthritic knees[8,9]. This treatment enables to address degenerative arthritis condition coexistent with septic arthritis and leads to successful infection control and better post-operative knee mobility. While this concept has been recently applied to the treatment of active primary glenohumeral arthritis, the current data in the literature are contradictory in terms of functional outcomes and patient satisfaction. Nonetheless, as summarized in Table 3 the available studies which deal with the topic of two-stage revision are focused on infected total shoulder arthroplasty. The results of patients with native advanced septic arthritis which are merged in theses cohorts, with no separate analysis provided for this specific subgroup. Further only in a small percentage of the patients in theses series a second-stage procedure with spacer removal and shoulder arthroplasty was performed[10-15]. The available data concerning functional and clinical outcomes is therefore limited to three cases reported by Magnan et al[15]. In their retrospective study, 3 patients were treated with a two-stage arthroplasty for primary septic arthritis with Constant shoulder score ranging 78-85 points and American shoulder and elbow society score ranging 20-22 points.

| Authors | Year of publication | Design | Native septic arthritis treated with cement spacer | Patients reimplanted | Mean interval | Mean follow-up |

| Themistocleous et al[11] | 2007 | Retrospective | 7/11 2/11 | 2/111 | 4 mo | 22 mo (15-26 mo) |

| Hattrup et al[10] | 2010 | Retrospective | 5/21 | 21/21 | 6.6 mo (Median: 3 mo) | 49 mo (24-109 mo) |

| Stine et al[12] | 2010 | Retrospective | 9/30 | 15/301 | 3-4 mo | 29 mo |

| Coffey et al[13] | 2010 | Retrospective | 5/16 | 12/161 | 3 mo (6-30 wk) | 20.5 mo (12-30 mo) |

| Twiss et al[14] | 2010 | Retrospective | 5/30 | 20/301 | 9.3 wk (6-30 wk) | 21.2 mo (12-40 mo) |

| Magnan et al[15] | 2014 | Retrospective | 5/7 | 3/7 | 7 mo (6-8 mo) | 40 mo |

In our series, despite the short interval for re-implantation, none of the patient had clinical or radiological sign of persistent infection at last follow-up. In a systematic review, McFarland reported a mean interval of 6 mo (range, 2-18 mo) to re-implantation among the different series[24]. Several authors reported a substantial risk of persistent infection after two-stage prosthesis exchange in case of prosthetic shoulder infections with recurrence rates ranging from 0% to 40%[25-32]. Nonetheless, two retrospective series reported no recurrence of infection after shoulder prosthesis implantation following a resection arthroplasty[18,29].

In our patients we used a custom made stemmed antibiotic-impregnated polymethyl methacrylate spacer. This technique has the potential to minimize intraarticular scaring, diminish dead space and provide a high local antibiotic concentration[32]. A recent retrospective study reported no statistical difference between stemmed and stemless spacer in term of reinfection rate, operation time, complication rate, or functional outcome after reimplantation. However, in our institution we still favor the potential advantage of a well fitted custom-made stemmed spacer being aware of the fact that there is limited evidence for optimal treatment even in the setup of prosthetic shoulder infections[33,34]. Definitive treatment with antibiotic spacer has been shown to be a reliable option in low-demand patients. There is a potential risk of glenoid erosions that could put in jeopardy a future reimplantation[24,35]. This option should therfore be carefully discussed with the patient.

In our series, ROM and functional scores at final follow-up were satisfying taking into consideration that functional results are low in case of irrigation and debridement for septic arthritis of higher stages or with associated rotator cuff tear[21,36]. Jeon et al[22] reported, in a retrospective series, a University of California at Los Angeles score of 23.7 points in patients with rotator cuff tear, and 29.0 points in patients without rotator cuff tear. In a retrospective series, Sabesan et al[26] reported average forward flexion of 123 ± 33°, external rotation of 26 ± 8° and mean Penn score of 66.4 points in patients treated with a two-staged reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Other series showed postoperative forward elevation from 89° to 119° and external rotation from 19° to 43°[21-23,25]. Garofalo et al[18] retrospectively reviewed ten patients with late sequelae of septic arthritis of the glenohumeral joint with open joint debridement, humeral head resection, and implantation of an antibiotic spacer. Five of them underwent a delayed (4 to 6 mo) reverse shoulder arthroplasty. At last follow-up, they demonstrated a mean active elevation of 98° and abduction of 70° (range 90–55°). The mean constant score was 56 points. No intraoperative or postoperative complications were observed.

Although we had no complication to deplore in our small series, the complication rates of two-stage reimplantation of shoulder prosthesis is high and vary from 35% to 73% including persistent infection, dislocation, fracture, pulmonary embolism among others[26,27,30,31].

This study should be interpreted in light of its potential limitations, mostly inherent to the retrospective design. However, due to the standardized clinical and radiological follow-up protocol and the excellent documentation through the orthopedic surgeons of our institution, most of the patient data we needed were available for the current analysis. Furthermore, the small number of patients included in this study should be mentioned. However, the data in the literature are limited and consist mainly of small case-series or case-reports.

In conclusion, our results indicate that salvage surgery, as described in our study, is a valuable treatment option in septic arthritis of the shoulder. The rising number of shoulder procedures performed in aging population with inherent higher risk factors could potentially lead to a growing number of septic glenohumeral arthritis. Multicenter studies are necessary to achieve a higher case load and evidence regarding these rare indications. Short interval two-stage approach for septic glenohumeral arthritis is a valid alternative treatment option for patient with advanced degenerative condition and/or irreparable rotator cuff tears. In our opinion, it should be reserved for selected patients with higher stage of infection, who failed to heal with arthroscopic or open lavage and debridement.

Septic arthritis of the glenohumeral joint is a relatively rare entity representing 3% to 15% of septic arthritis. It can nonetheless lead to major complications such as bone and cartilage destruction if treatment is delayed. Early treatment is therefore mandatory to alleviate pain and restore optimal function. Open or arthroscopic irrigation and debridement associated with targeted intravenous antibiotic therapy is effective to eradicate the infection. However, in patients with advanced osteoarthritic changes and/or massive rotator cuff tendon tears, infection eradication can be challenging to achieve and the functional outcome is often not satisfying even after successful infection eradication.

The motivation behind this study was to evaluate a two-stage approach with initial resection of the native infected articular surfaces, implantation of a cement spacer before final treatment with a total shoulder arthroplasty in a second stage. While this treatment option is gaining popularity in recent years, the evidence in the literature remains limited.

The available studies which deal with the topic of two-stage revision are focused on infected total shoulder arthroplasty. The results of patients with native advanced septic arthritis which are merged in theses cohorts, with no separate analysis provided for this specific subgroup. The aim of our study was reported our results of a short interval two-stage arthroplasty approach for septic arthritis with concomitant advanced degenerative changes of the shoulder joint.

We retrospectively included five consecutive patients over a five-year period and evaluated the therapeutic management and the clinical outcome assessed by disability of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) score and subjective shoulder value (SSV). All procedures were performed through a deltopectoral approach and consisted in a debridement and synovectomy, articular surface resection and insertion of a custom made antibiotic enriched cement spacer. Shoulder arthroplasty was performed in a second stage.

Mean age was 61 years (range, 47-70 years). Four patients had previous surgeries ahead of the septic arthritis. All patients had a surgical debridement ahead of the index procedure. Mean follow-up was 13 mo (range, 6-24 mo). Persistent microbiological infection was confirmed in all five cases at the time of the first stage of the procedure. The shoulder arthroplasties were performed 6 to 12 wk after insertion of the antibiotic-loaded spacer. There were two hemi and three reverse shoulder arthroplasties. Infection was successfully eradicated in all patients. The clinical outcome was satisfactory with a mean DASH score and SSV of 18.4 points and 70%, respectively.

Our study indicates that short interval two-stage approach for septic glenohumeral arthritis is a valid alternative treatment option for patient with advanced degenerative condition and/or irreparable rotator cuff tears. The main advantage of this novel approach is that by treating the underlying bony pathology in terms of resecting the arthritic bone the chances of successful infection eradication are increased and at the same time it allows for adequate pain control and improvement of functional outcomes. In our opinion, it should be reserved for selected patients with higher stage of infection, who failed to heal with arthroscopic or open lavage and debridement

The rising number of shoulder procedures performed in aging population with inherent higher risk factors could potentially lead to a growing number of septic glenohumeral arthritis. Multicenter studies are necessary to achieve a higher case load and evidence regarding these rare indications.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Switzerland

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhai KF, Anand A, Peng BG S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Memon M, Kay J, Ginsberg L, de Sa D, Simunovic N, Samuelsson K, Athwal GS, Ayeni OR. Arthroscopic Management of Septic Arthritis of the Native Shoulder: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:625-646.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sultana S, Dey R, Bishayi B. Dual neutralization of TNFR-2 and MMP-2 regulates the severity of S. aureus induced septic arthritis correlating alteration in the level of interferon gamma and interleukin-10 in terms of TNFR2 blocking. Immunol Res. 2018;66:97-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Farrow L. A systematic review and meta-analysis regarding the use of corticosteroids in septic arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhai KF, Duan H, Cui CY, Cao YY, Si JL, Yang HJ, Wang YC, Cao WG, Gao GZ, Wei ZJ. Liquiritin from Glycyrrhiza uralensis Attenuating Rheumatoid Arthritis via Reducing Inflammation, Suppressing Angiogenesis, and Inhibiting MAPK Signaling Pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:2856-2864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhai KF, Duan H, Chen Y, Khan GJ, Cao WG, Gao GZ, Shan LL, Wei ZJ. Apoptosis effects of imperatorin on synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis through mitochondrial/caspase-mediated pathways. Food Funct. 2018;9:2070-2079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhai KF, Duan H, Khan GJ, Xu H, Han FK, Cao WG, Gao GZ, Shan LL, Wei ZJ. Salicin from Alangium chinense Ameliorates Rheumatoid Arthritis by Modulating the Nrf2-HO-1-ROS Pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:6073-6082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Leslie BM, Harris JM, Driscoll D. Septic arthritis of the shoulder in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1516-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shaikh AA, Ha CW, Park YG, Park YB. Two-stage approach to primary TKA in infected arthritic knees using intraoperatively molded articulating cement spacers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2201-2207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nazarian DG, de Jesus D, McGuigan F, Booth RE. A two-stage approach to primary knee arthroplasty in the infected arthritic knee. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:16-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hattrup SJ, Renfree KJ. Two-stage shoulder reconstruction for active glenohumeral sepsis. Orthopedics. 2010;33:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Themistocleous G, Zalavras C, Stine I, Zachos V, Itamura J. Prolonged implantation of an antibiotic cement spacer for management of shoulder sepsis in compromised patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:701-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stine IA, Lee B, Zalavras CG, Hatch G, Itamura JM. Management of chronic shoulder infections utilizing a fixed articulating antibiotic-loaded spacer. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:739-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Coffey MJ, Ely EE, Crosby LA. Treatment of glenohumeral sepsis with a commercially produced antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:868-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Twiss TJ, Crosby LA. Treatment of the Infected Total Shoulder Arthroplasty With Antibiotic-Impregnated Cement Spacers. Seminars in Arthroplasty. 2010;21:204-208. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Magnan B, Bondi M, Vecchini E, Samaila E, Maluta T, Dall'Oca C. A preformed antibiotic-loaded spacer for treatment for septic arthritis of the shoulder. Musculoskelet Surg. 2014;98:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Le Dantec L, Maury F, Flipo RM, Laskri S, Cortet B, Duquesnoy B, Delcambre B. Peripheral pyogenic arthritis. A study of one hundred seventy-nine cases. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1996;63:103-110. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lossos IS, Yossepowitch O, Kandel L, Yardeni D, Arber N. Septic arthritis of the glenohumeral joint. A report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:177-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Garofalo R, Flanagin B, Cesari E, Vinci E, Conti M, Castagna A. Destructive septic arthritis of shoulder in adults. Musculoskelet Surg. 2014;98:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Duncan SF, Sperling JW. Treatment of primary isolated shoulder sepsis in the adult patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1392-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pfeiffenberger J, Meiss L. Septic conditions of the shoulder--an up-dating of treatment strategies. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1996;115:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stutz G, Kuster MS, Kleinstück F, Gächter A. Arthroscopic management of septic arthritis: stages of infection and results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jeon IH, Choi CH, Seo JS, Seo KJ, Ko SH, Park JY. Arthroscopic management of septic arthritis of the shoulder joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1802-1806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Böhler C, Pock A, Waldstein W, Staats K, Puchner SE, Holinka J, Windhager R. Surgical treatment of shoulder infections: a comparison between arthroscopy and arthrotomy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1915-1921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McFarland EG, Rojas J, Smalley J, Borade AU, Joseph J. Complications of antibiotic cement spacers used for shoulder infections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1996-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Coste JS, Reig S, Trojani C, Berg M, Walch G, Boileau P. The management of infection in arthroplasty of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sabesan VJ, Ho JC, Kovacevic D, Iannotti JP. Two-stage reimplantation for treating prosthetic shoulder infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2538-2543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Strickland JP, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. The results of two-stage re-implantation for infected shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:460-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sperling JW, Kozak TK, Hanssen AD, Cofield RH. Infection after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cuff DJ, Virani NA, Levy J, Frankle MA, Derasari A, Hines B, Pupello DR, Cancio M, Mighell M. The treatment of deep shoulder infection and glenohumeral instability with debridement, reverse shoulder arthroplasty and postoperative antibiotics. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:336-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Buchalter DB, Mahure SA, Mollon B, Yu S, Kwon YW, Zuckerman JD. Two-stage revision for infected shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:939-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jacquot A, Sirveaux F, Roche O, Favard L, Clavert P, Molé D. Surgical management of the infected reversed shoulder arthroplasty: a French multicenter study of reoperation in 32 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1713-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ramsey ML, Fenlin JM. Use of an antibiotic-impregnated bone cement block in the revision of an infected shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Padegimas EM, Narzikul A, Lawrence C, Hendy BA, Abboud JA, Ramsey ML, Williams GR, Namdari S. Antibiotic Spacers in Shoulder Arthroplasty: Comparison of Stemmed and Stemless Implants. Clin Orthop Surg. 2017;9:489-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Romanò CL, Borens O, Monti L, Meani E, Stuyck J. What treatment for periprosthetic shoulder infection? Results from a multicentre retrospective series. Int Orthop. 2012;36:1011-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mahure SA, Mollon B, Yu S, Kwon YW, Zuckerman JD. Definitive Treatment of Infected Shoulder Arthroplasty With a Cement Spacer. Orthopedics. 2016;39:e924-e930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kirchhoff C, Braunstein V, Buhmann Kirchhoff S, Oedekoven T, Mutschler W, Biberthaler P. Stage-dependant management of septic arthritis of the shoulder in adults. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1015-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |