Copyright

©The Author(s) 2016.

World J Orthop. Oct 18, 2016; 7(10): 670-677

Published online Oct 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.670

Published online Oct 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.670

Figure 1 Preoperative physical appearance with loss of anterior axillary fold (black arrow).

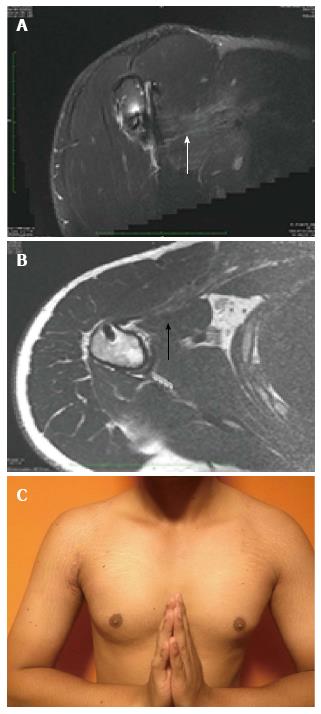

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance imaging report showing near complete tear (arrow) of Pectoralis major muscle.

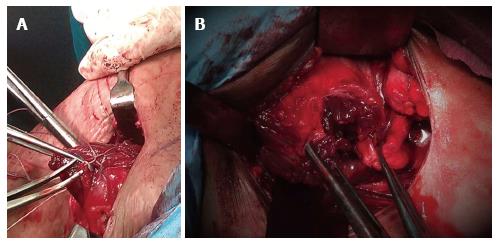

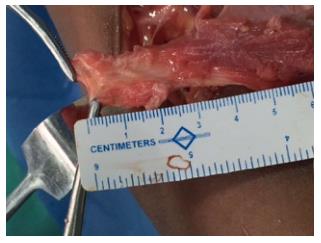

Figure 3 Torn pectoralis major tendon Sternal head identified and whip sutured (A); and a complete tear of both sternal and clavicular heads, held separately with forceps after mobilization (B).

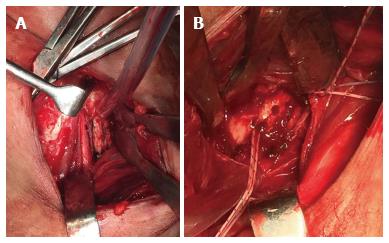

Figure 4 Exposure of bicipital groove (A), Biceps tendon is protected.

Corkscrew anchors (double loaded) are deployed into the lateral lip of bicipital groove (B).

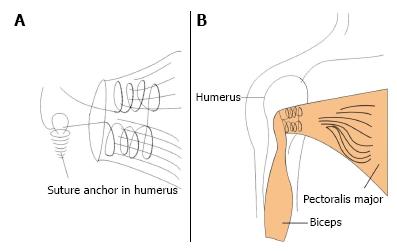

Figure 5 Box sliding technique.

Musculotendinous unit was whipstiched (this makes like a box covering the broad area of delicate muscle to prevent cutting through the musclotendinous unit) and sliding Nikky’s knot was used to push the tendon to bone (A). A final picture after the torn tendon has been secured to the lateral lip of bicipital groove with anchors (B).

Figure 6 Magnetic resonance imaging at 6 mo follow up showing excellent continuity (arrow) and the bulk of pectoralis major muscle after repair (A, B); restoration of the anterior axillary fold after surgery (C).

Figure 7 In acute cases reparable length of the tendon may be available for repair, but in chronic cases it is mainly muscle, which remains available to be attached back to the bone (Figure 3).

- Citation: Joshi D, Jain JK, Chaudhary D, Singh U, Jain V, Lal A. Outcome of repair of chronic tear of the pectoralis major using corkscrew suture anchors by box suture sliding technique. World J Orthop 2016; 7(10): 670-677

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i10/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.670