Published online Dec 20, 2018. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v9.i8.200

Peer-review started: July 12, 2018

First decision: October 8, 2018

Revised: November 7, 2018

Accepted: November 15, 2018

Article in press: November 15, 2018

Published online: December 20, 2018

Processing time: 162 Days and 10.2 Hours

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC) is a rare, low-grade, malignant tumor that constitutes less than one percent of all salivary gland tumors. To date, only one other case report has described radiation-associated EMC in the English language medical literature.

In this report, we describe the case of a 56-year-old male patient who presented with a neck mass diagnosed as EMC of the left submandibular gland approximately 30 years after mantle field radiation and chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. Treatment included resection, re-resection with nodal dissection, and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. This patient was also diagnosed with 4 other secondary malignancies, including stage IV diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the abdomen with subsequent brain metastases, low-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung, Hurthle cell adenoma, and small B cell lymphoma before the patient expired. This case provides important information regarding the pathology, clinical sequelae, and management of a patient diagnosed with radiation-associated EMC amidst four concurrent malignancies.

Further investigation is needed on the efficacy of adjuvant radiotherapy in EMC, especially atypical EMC.

Core tip: We describe the second known case of radiation-associated epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC). This patient received chemotherapy and radiation therapy thirty years prior for Hodgkin lymphoma, and in addition to EMC was also diagnosed with four other malignancies in a span of five years. Because of worrisome histopathologic features atypical for EMC and pathologic stage of this patient, this patient was treated more aggressively with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. This case provides important information regarding the pathology, clinical sequelae, and management of radiation-associated EMC. Further investigation is needed on the efficacy of adjuvant radiotherapy in EMC, especially atypical EMC.

- Citation: Khattab MH, Sherry AD, Ahlers CG, Kirschner AN. Radiation-associated epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma among five secondary malignancies: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Oncol 2018; 9(8): 200-207

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v9/i8/200.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v9.i8.200

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC) is a rare, low-grade malignant tumor of the salivary gland. Originally described by Donath et al[1] in 1972, EMC first appeared in the World Health Organization classification of salivary gland tumors in 1991[2]. Representing less than one percent of all salivary gland tumors, EMC typically manifests as a bulky, slowly growing mass primarily within the parotid gland or less commonly the submandibular glands, minor salivary glands, or palate[3]. EMC is more prevalent in females and most often presents in the seventh decade of life[3]. EMC is recognizable histologically as a biphasic tumor, characterized by inner ductal epithelial cells and abundant outer clear myoepithelial cells[2,3]. Pathologic subcategorizations of EMC include double clear EMC, oncocytic EMC, sebaceous EMC, apocrine EMC, EMC ex pleomorphic adenoma, and EMC with high-grade transformation (HGT)[4]. HGT is a transition from low-grade to high-grade morphology with loss of the original histological characteristics. EMC with HGT is exceedingly rare[4]. The minimum recommended treatment for EMC is surgical resection, although local recurrence after resection has been reported in 23%-50% of cases[3]. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy (RT) are also appropriate therapeutic options especially with nodal involvement or metastatic disease, although very few data exist regarding their efficacy[5].

To the best of our knowledge, only one case report has thus far described RT-associated EMC in the English language medical literature[6]. In this previous report, a 48-year-old male was diagnosed with right submandibular high-grade EMC 25 years after mantle field RT. Multiple resections as well as adjuvant RT and chemotherapy were required due to multiple recurrences over a 4-year period. Although EMC is typically a low-grade tumor, this report conjectured an etiologic association between the extensive necrosis profile and high mitotic activity evident on pathological exam, as well as the unusually young age of the patient, and the course of previous RT.

While seldom utilized today, mantle field RT was the standard of care for Hodgkin lymphoma in the 1960’s because of enhanced curative potential compared to more focal treatment. Historically, RT treatment paradigms were built on the concept of extended field radiation therapy (EF-RT), wherein both the primary site and regional lymphatic groups were treated. EF-RT was categorized into mantle field RT and inverted-Y field RT. Mantle field RT covered the cervical, mid-chest, and axillary lymph nodes, while inverted-Y field RT covered the subdiaphragmatic field including all para-aortic, iliac, upper femoral, and inguinal lymph nodes[7]. Notably, mantle field RT has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer[8]. According to De Bruin et al[8], mantle field RT (involving the axillary, mediastinal, and neck nodes) was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk of breast cancer compared with similarly dosed (36 to 44 Gy) mediastinal nodes alone. Mantle field RT has also been associated with increased cardiac morbidity and mortality[9].

After subtotal resection of EMC, the patient presented to our institution for evaluation. The patient reported that, from discovery until dissection, the neck mass was without symptomatic changes and was neither painful nor enlarging.

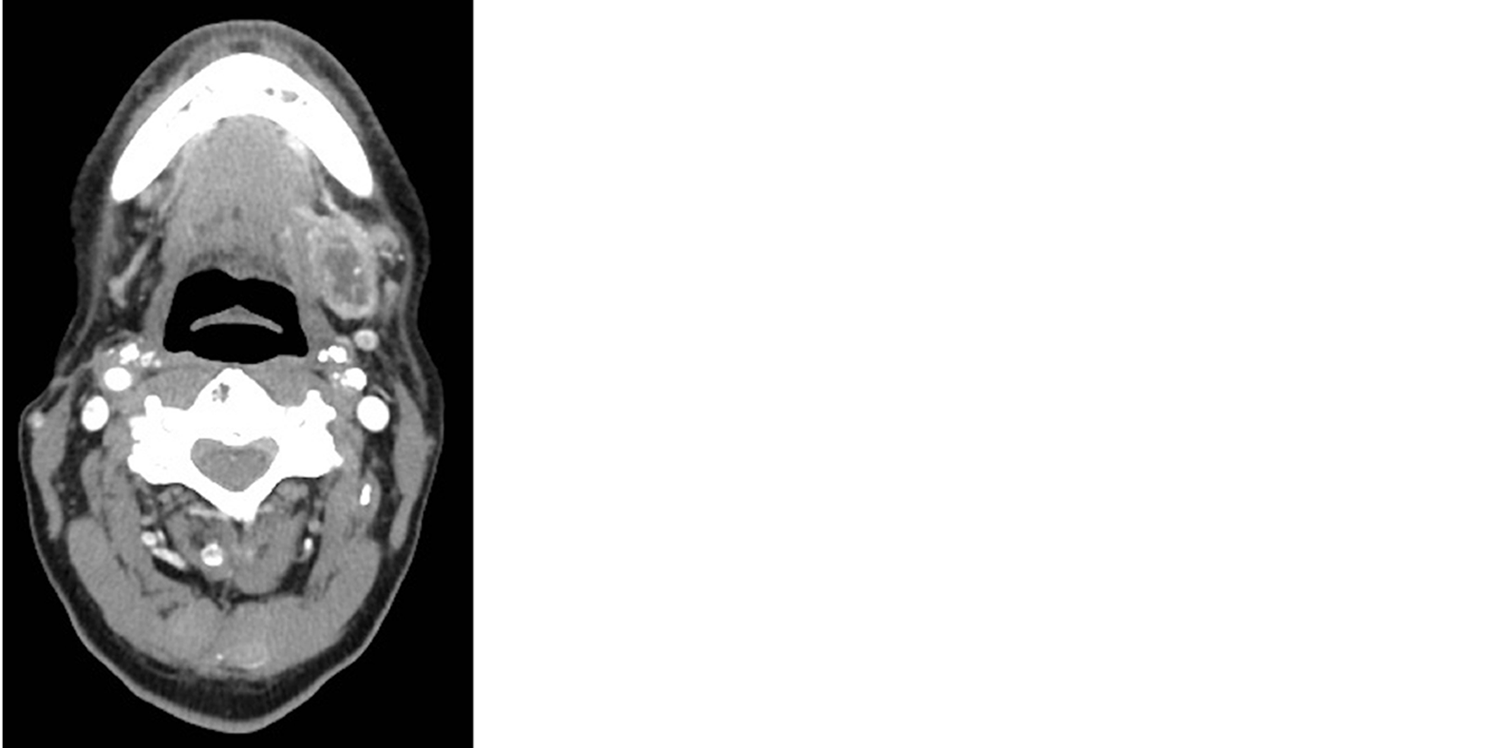

At the age of 56, the patient presented with a chief complaint of a neck mass detected while shaving. Computerized tomography (CT) scan of his neck showed a heterogeneous ovoid mass in the left submandibular region measuring 2.9 cm × 1.8 cm (Figure 1). The CT scan also demonstrated an enlarged left paramedial submental lymph node measuring 1.6 cm × 0.9 cm. Biopsy of the neck mass revealed EMC staining positive for CK7, CKAE1/AE3, CK903, S100, and smooth muscle actin and negative for CK20, PAX8, GATA, CDX2, GFAP. Infiltrates into soft tissue were noted along with fragments of salivary gland with fibrosis and atrophy. The left submandibular mass was then resected in piecemeal fashion, with final pathology report confirming EMC.

At the age of 19, this male patient presented with Hodgkin lymphoma and underwent mantle field RT, chemotherapy, and splenectomy. He did not exhibit evidence of recurrence. At the age of 52, stomach biopsy revealed diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with positron emission tomography (PET) scan displaying diffuse disease in the right axilla, mediastinum, multiple abdominal lymph nodes, appendicular skeleton, and liver. For DLBCL treatment, the patient received denosumab and six cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Shortly after completing therapy, he presented with dizziness, ataxia, and memory loss. Brain MRI showed two ring-enhancing lesions consistent with metastasis, one in the right temporal lobe and the other in the left posterior fossa adjacent to the fourth ventricle. He underwent subsequent whole brain radiation therapy with 3960 cGy delivered in 22 fractions as well as intrathecal cytarabine.

In addition to his oncologic history, his past medical history was notable for coronary artery disease, hypertension, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and mini-stroke. His surgical history was remarkable coronary artery bypass grafting x 4 vessels, right carotid endarterectomy, appendectomy, and aortic valve replacement. Family history of cancer included a maternal grandfather with lung cancer, a maternal uncle with colon cancer, and a paternal grandfather with lung cancer. There were no first degree relatives with a history of cancer, heart disease, alcoholism, asthma, bleeding disorder, diabetes, or thyroid disease. Social history was remarkable for a 32-pack year smoking history, asbestos exposure, and no alcohol or illicit drug use.

Physical exam was notable for bilateral dense fibrosis.

Laboratory diagnosis was deferred, as definitive pathological diagnosis was available.

MRI and PET did not show evidence of visible residual local EMC.

Genetic testing was deferred.

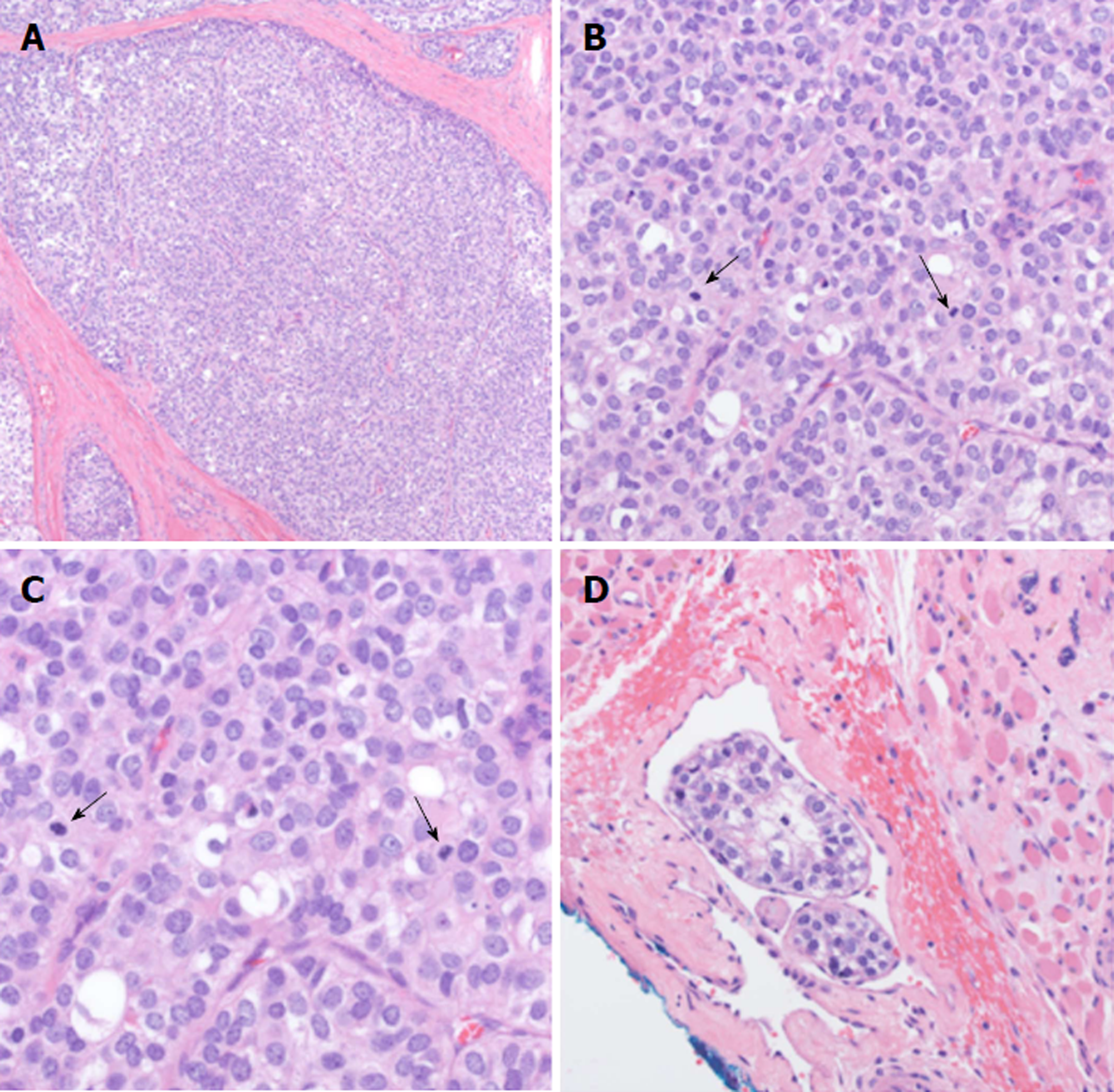

Given the piecemeal manner in which the cancer was removed, a multidisciplinary tumor board concluded that the patient required revision surgery with additional neck dissection for concerning nodes unaddressed by the original surgery. The patient proceeded with resection of the left submandibular gland with dissection of level IA, IB, and suprahyoid neck nodes. Histologic examination revealed EMC in 1/2 left level IB lymph nodes and 0/3 left level IA lymph nodes staged as pT2pN1M0. The pathology showed extensive lymphovascular invasion and positive margins on the primary mass (Figure 2). Based on the high probability of residual microscopic disease, the patient elected to proceed with adjuvant chemoradiation.

For adjuvant treatment of EMC, the patient’s left hemineck received intensity-modulated radiation therapy consisting of 5040 cGy in 28 fractions, followed by a 3D-boost of 1620 cGy in 9 fractions to the left submandibular tumor bed and adjacent level IB lymph node region. The cumulative dose totaled 6660 cGy in 37 fractions. Concurrent chemotherapy consisted of weekly of carboplatin and paclitaxel. After completing chemoradiotherapy, the patient showed no evidence of EMC disease on history, physical exam, and CT imaging. At this time, he reported some sequelae of treatment including xerostomia and fibrosis of the neck tissues.

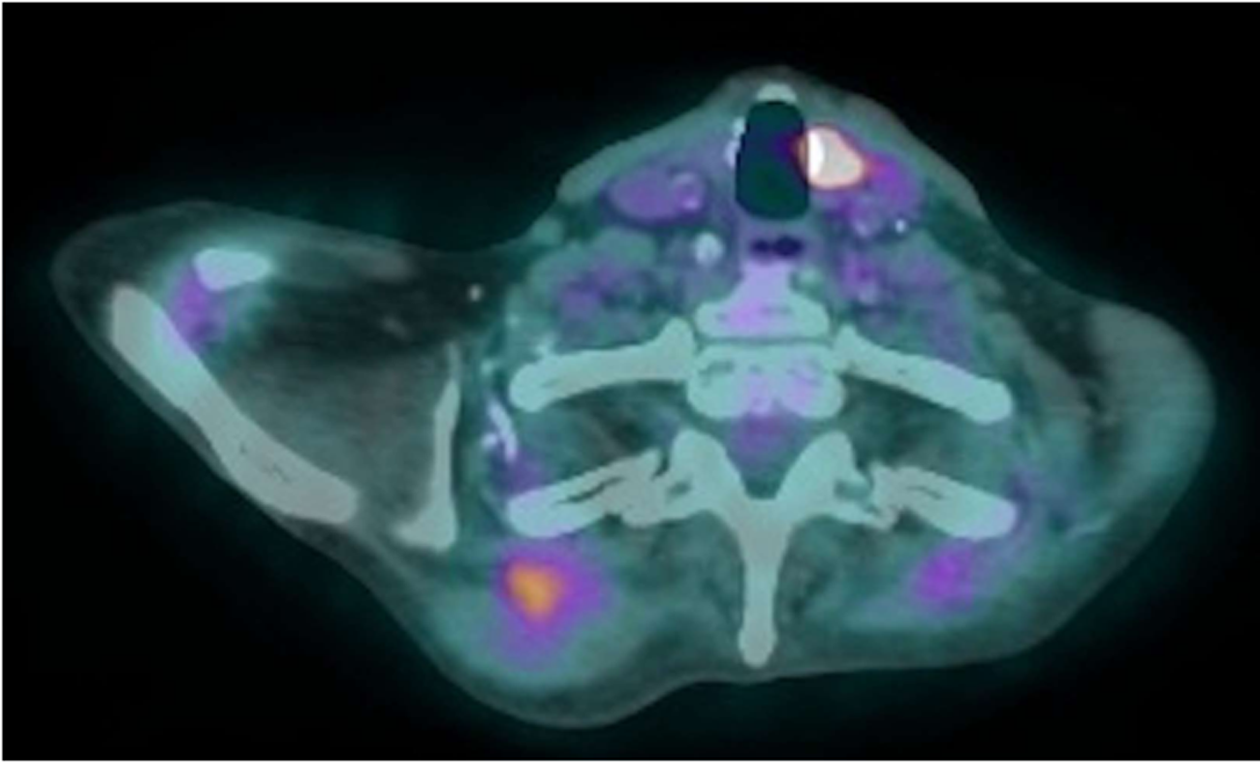

While awaiting chemoradiation for EMC, at the age of 56, a restaging PET scan demonstrated mild to moderate 2-18F-fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake in an irregular nodular density measuring 1.7 cm × 1.3 cm in the right upper lobe of the lung (Figure 3). Comparison to a previous CT scan showed interval growth of the nodule from 1.4 cm × 1.0 cm. Bronchoscopy with biopsy revealed a neuroendocrine tumor (NET). Immunopanel showed the tumor to be positive for CAM 5.2, TTF1, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. A Ki67 immunoperoxidase stain exhibited a low proliferation rate of less than 3%, indicative of a low-grade neoplasm. Notably, the patient denied any cough, shortness of breath, diarrhea, flushing, or weight loss, and consequently elected for observation with close monitoring.

The PET scan also demonstrated an intensely FDG focus measuring 0.6 cm × 0.7 cm in the anterior medial aspect of the left thyroid lobe (Figure 4). Thyroid ultrasound with Doppler displayed an oblong mildly hypoechoic nodule with peripheral and internal vascularity. Fine needle aspiration revealed a follicular lesion of undetermined significance composed predominantly of Hurthle cells. Given the benign nodular hyperplasia of the thyroid nodule compared to the micrometastatic EMC, the patient elected to first proceed with chemoradiation for EMC followed by hemithyroidectomy for the Hurthle-cell adenomatoid nodule.

Ten months post-chemoradiotherapy, a follow-up CT scan displayed interval growth of the right upper lobe NET along with several new bilateral pulmonary nodules. PET scan noted a new intensely FDG avid focus in the left pterygoid muscle along with intensely avid hilar lymphadenopathy and moderately avid mediastinal lymph nodes. Biopsy of the pulmonary nodules and mediastinal lymph nodes was negative for malignancy. Based on the interval growth of the NET, the patient elected for stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) to the right lung. This lesion received a total dose of 5250 cGy over 5 fractions with 1 isocenter and 2 VMAT beams. In each fraction, 1050 cGy covered 95% of the planned treatment volume (PTV) while 90% of the prescription dose covered 99% of the PTV.

Two months after completing SBRT, the patient presented to the emergency department with epistaxis and a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio secondary to warfarin. A fall while hospitalized lead to altered mental status and hypoxic respiratory failure, prompting transfer to the intensive care unit and intubation. He subsequently developed pneumonia and sepsis with a vasopressor requirement as well as bilateral pleural effusions requiring repeated therapeutic thoracentesis. Flow cytometry of the pleural fluid was notable for a CD10-positive lambda-skewed B cell population suspicious for a small B cell lymphoma vs follicular lymphoma, with a negative peripheral blood flow cytometry. After discussion with his family regarding goals of care, he transferred to the palliative care unit and subsequently inpatient hospice, where he expired shortly thereafter.

Secondary malignancy after Hodgkin lymphoma is not an infrequent occurrence. According to Schaapvel and co-authors, even 40 years after treatment, survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma are at an increased risk for secondary cancers, with the cumulative incidence approaching 48.5%[10]. Additionally, a recent retrospective study by Patel et al. investigating 1541 stage I and stage II Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated from 1968 to 2007 revealed that, after median follow-up of 15.2 years (35% of patients with > 20 years of follow up), 395 patients had died of all causes, 85 patients had died from Hodgkin lymphoma, 168 had died from secondary malignancies (25 hematologic and 143 nonhematologic), 70 had died from cardiovascular causes, and 21 had died from pulmonary causes[11]. Remarkably, as these data show, more patients died from secondary malignancies than from the primary Hodgkin lymphoma.

The patient presented in this case report developed multiple malignancies, including DLBCL, EMC, Hurthle cell adenoma, low grade NET, and small B cell lymphoma after chemotherapy and RT of Hodgkin lymphoma three decades prior. Of these 4 malignancies, EMC is the most likely to be secondary to RT in this patient. Its location in left submandibular gland is within the previous mantle field RT treatment area, fulfilling Cahan’s criteria for RT-associated secondary malignancy[12]. Additionally, the pathology of this patient’s EMC was atypical. While characteristically a low-grade, indolent tumor, this EMC was an aggressive, invasive malignancy, in keeping with the only previously reported case of RT-associatec EMC[6]. Other RT-induced secondary malignancies, including glioma, sarcoma, and meningioma, are more often higher grade and more aggressive than their sporadic counterparts[13-15]. Regarding the other malignant entities in this patient, including DLBCL, Hurthle cell adenoma, and low-grade NET, these may be secondary to RT for Hodgkin lymphoma, as they do fulfill Cahan’s criteria. Thyroid malignancies secondary to RT including Hurthle cell adenoma are well-described, and there are reports of DLBCL secondary to radiation[16-18]. A case of quadruple neoplasms following RT therapy has also been published[19]. While family history was negative for first degree relatives with cancer, this patient may have had an unstable genomic background more susceptible to mutagenic insult that, in combination with a strong tobacco history, resulted in a lower threshold for carcinogenesis secondary to mantle field RT.

Importantly, clinical management guidelines of DLBCL, Hurthle cell adenoma, NET, and small B cell lymphoma are well-described; however, EMC, a rare entity, is less well-understood, especially even rarer high grade variants. EMC is most typically treated with surgery, although local recurrence occurs in one-fourth to one-half of all cases[3]. To risk stratify EMC based on pathological features, a retrospective study evaluated 61 tumors and reported positive margin status, angiolymphatic invasion, tumor necrosis, and myoepithelial anaplasia as significantly associated with shortened disease free survival[20]. This patient with positive margins, lymphovascular invasion, and nodal involvement was certainly at an elevated risk for recurrence. However, very few data have been reported on treatment paradigms for high risk patients, and the decision to pursue adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in this patient was in part based on evidence extrapolated from other salivary gland tumors. The largest study of EMC retrospectively analyzed the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) database and did not find a disease specific survival benefit for patients receiving adjuvant RT[21]. However, such data are more applicable to classic quiescent EMC than higher grade or RT-associated EMC. RT has been included in treatment plans since WHO inclusion in 1991, and some authors advocate for a refined incorporation of adjuvant RT in the setting of recurrent or high risk EMC[22,23]. Metastatic cases, while uncommon, have a poor prognosis when observed without chemoradiotherapy[24]. Finally, a biological basis may exist for an enhanced response to RT for more aggressive cancers compared to more indolent tumors[25].

In summary, given the scarcity of information about EMC after Hodgkin lymphoma, this case report provides vital information regarding the pathology, clinical sequelae, and treatment of EMC after Hodgkin lymphoma. Furthermore, this case provides a unique illustration of a quintet of malignancies following RT and chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with a history of treated Hodgkin lymphoma merit long-term follow-up due to increased risk of secondary malignancy. Further investigation is needed on the efficacy of adjuvant RT in EMC, especially atypical EMC.

Patients with a history Hodgkin lymphoma treated with mantle field RT are at risk for secondary malignancies. This includes on rare occasions EMC. We illustrate that radiation-associated EMC can be treated with resection and adjuvant chemoradiation.

We also thank Dr. Kelli Boyd for her assistance in obtaining pathology images.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dholaria B, He J, Kupeli S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

| 1. | Donath K, Seifert G, Schmitz R. [Diagnosis and ultrastructure of the tubular carcinoma of salivary gland ducts. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the intercalated ducts]. Virchows Arch A Pathol Pathol Anat. 1972;356:16-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Seifert G, Sobin LH. Histologic typing of salivary gland tumours. World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumours. Berlin: Springer-Veflag 1991; 23-24. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Politi M, Robiony M, Avellini C, Orsaria M. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland: Clinicopathological aspect, diagnosis and surgical consideration. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li B, Yang H, Hong X, Wang Y, Wang F. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma with high-grade transformation of parotid gland: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yamazaki H, Ota Y, Aoki T, Kaneko A. Lung metastases of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland successfully treated with chemotherapy: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:220-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mann JM, Kellman RM, Hahn SS, de la Roza GL, Gajra A. Radiation-induced epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma in a patient previously treated with mantle-field radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. Head Neck. 2015;37:E96-E98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Witkowska M, Majchrzak A, Smolewski P. The role of radiotherapy in Hodgkin’s lymphoma: what has been achieved during the last 50 years? Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:485071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De Bruin ML, Sparidans J, van’t Veer MB, Noordijk EM, Louwman MW, Zijlstra JM, van den Berg H, Russell NS, Broeks A, Baaijens MH. Breast cancer risk in female survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: lower risk after smaller radiation volumes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4239-4246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maraldo MV, Brodin NP, Vogelius IR, Aznar MC, Munck Af Rosenschöld P, Petersen PM, Specht L. Risk of developing cardiovascular disease after involved node radiotherapy versus mantle field for Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:1232-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schaapveld M, Aleman BM, van Eggermond AM, Janus CP, Krol AD, van der Maazen RW, Roesink J, Raemaekers JM, de Boer JP, Zijlstra JM. Second Cancer Risk Up to 40 Years after Treatment for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2499-2511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Patel CG, Michaelson E, Chen YH, Silver B, Marcus KJ, Stevenson MA, Mauch PM, Ng AK. Reduced Mortality Risk in the Recent Era in Early-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients Treated With Radiation Therapy With or Without Chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100:498-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cahan WG, Woodard HQ, Higinbotham NL, Stewart FW, Coley BL. Sarcoma arising in irradiated bone: report of eleven cases. 1948. Cancer. 1998;82:8-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rosko AJ, Birkeland AC, Chinn SB, Shuman AG, Prince ME, Patel RM, McHugh JB, Spector ME. Survival and Margin Status in Head and Neck Radiation-Induced Sarcomas and De Novo Sarcomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157:252-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yamanaka R, Hayano A, Kanayama T. Radiation-Induced Meningiomas: An Exhaustive Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2017;97:635-644.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ng I, Tan CL, Yeo TT, Vellayappan B. Rapidly Fatal Radiation-induced Glioblastoma. Cureus. 2017;9:e1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Arganini M, Behar R, Wu TC, Straus F 2nd, McCormick M, DeGroot LJ, Kaplan EL. Hürthle cell tumors: a twenty-five-year experience. Surgery. 1986;100:1108-1115. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Chaudhuri AA, Xavier MF. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBCL-LT) in the setting of prior radiation therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:371-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Papanastasiou L, Pappa T, Dasou A, Kyrodimou E, Kontogeorgos G, Samara C, Bacaracos P, Galanopoulos A, Piaditis G. Case report: Primary pituitary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma developed following surgery and radiation of a pituitary macroadenoma. Hormones (Athens). 2012;11:488-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Szymanski LJ, Sibug Saber ME, Kim JW, Go JL, Zada G, Rao N, Hurth KM. Quadruple Neoplasms following Radiation Therapy for Congenital Bilateral Retinoblastoma. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2017;4:33-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seethala RR, Barnes EL, Hunt JL. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma: a review of the clinicopathologic spectrum and immunophenotypic characteristics in 61 tumors of the salivary glands and upper aerodigestive tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:44-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vázquez A, Patel TD, D’Aguillo CM, Abdou RY, Farver W, Baredes S, Eloy JA, Park RC. Epithelial-Myoepithelial Carcinoma of the Salivary Glands: An Analysis of 246 Cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nguyen S, Perron M, Nadeau S, Odashiro AN, Corriveau MN. Epithelial Myoepithelial Carcinoma of the Nasal Cavity: Clinical, Histopathological, and Immunohistochemical Distinction of a Case Report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018;26:342-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Simpson RH, Clarke TJ, Sarsfield PT, Gluckman PG. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of salivary glands. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:419-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen MY, Vyas V, Sommerville R. Epithelial-Myoepithelial Carcinoma of the Base of Tongue with Possible Lung Metastases. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:4973573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Baskar R, Dai J, Wenlong N, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Biological response of cancer cells to radiation treatment. Front Mol Biosci. 2014;1:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |