Published online Oct 10, 2017. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i5.412

Peer-review started: March 24, 2017

First decision: May 10, 2017

Revised: May 27, 2017

Accepted: July 14, 2017

Article in press: July 17, 2017

Published online: October 10, 2017

Processing time: 186 Days and 16.1 Hours

To assess the clinical significance of prophylactic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection (LPLND) in stage IV low rectal cancer.

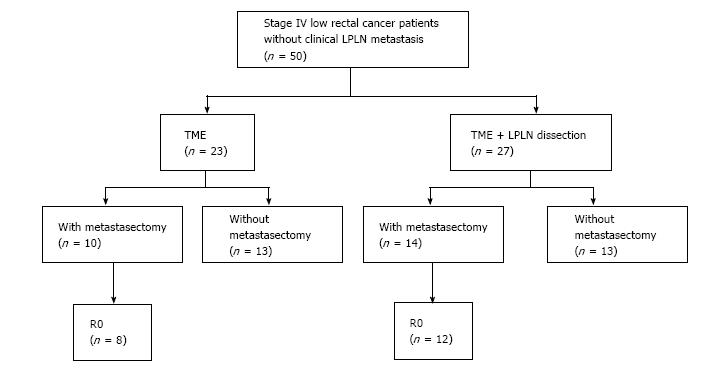

We selected 71 consecutive stage IV low rectal cancer patients who underwent primary tumor resection, and enrolled 50 of these 71 patients without clinical LPLN metastasis. The patients had distant metastasis such as liver, lung, peritoneum, and paraaortic LN. Clinical LPLN metastasis was defined as LN with a maximum diameter of 10 mm or more on preoperative pelvic computed tomography scan. All patients underwent primary tumor resection, 27 patients underwent total mesorectal excision (TME) with LPLND (LPLND group), and 23 patients underwent only TME (TME group). Bilateral LPLND was performed simultaneously with primary tumor resection in LPLND group. R0 resection of both primary and metastatic sites was achieved in 20 of 50 patients. We evaluated possible prognostic factors for 5-year overall survival (OS), and compared 5-year cumulative local recurrence between the LPLND and TME groups.

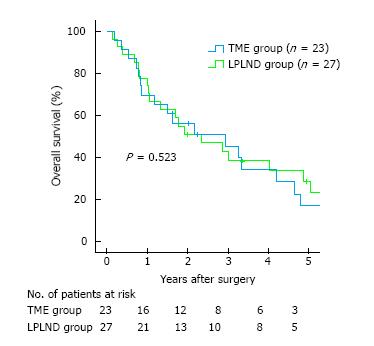

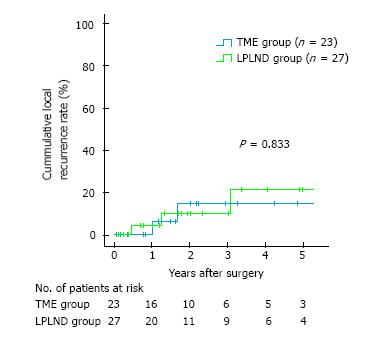

For OS, univariate analyses revealed no significant benefit in the LPLND compared with the TME group (28.7% vs 17.0%, P = 0.523); multivariate analysis revealed that R0 resection was an independent prognostic factor. Regarding cumulative local recurrence, the LPLND group showed no significant benefit compared with TME group (21.4% vs 14.8%, P = 0.833).

Prophylactic LPLND shows no oncological benefits in patients with Stage IV low rectal cancer without clinical LPLN metastasis.

Core tip: The clinical significance of prophylactic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection (LPLND) in stage IV low rectal cancer has not been proven. In this study, we showed two main findings concerning treatment strategy in these patients. First, prophylactic LPLND was not a significant prognostic factor for overall survival and did not contribute local control. Second, R0 resection was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival. These results suggest that prophylactic LPLND is not an important component of surgical treatment in stage IV low rectal cancer patients.

- Citation: Tamura H, Shimada Y, Kameyama H, Yagi R, Tajima Y, Okamura T, Nakano M, Nakano M, Nagahashi M, Sakata J, Kobayashi T, Kosugi SI, Nogami H, Maruyama S, Takii Y, Wakai T. Prophylactic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection in stage IV low rectal cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2017; 8(5): 412-419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v8/i5/412.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v8.i5.412

In rectal cancer, lymphatic spread accords with the anatomical level of the tumor[1,2]. When the tumor is located above the peritoneal reflection, lymphatic cancer metastasis is predominantly associated with upward mesenteric spread along perirectal vessels originating from the inferior mesenteric artery. In contrast, when the tumor is located at or below the peritoneal reflection, lymphatic cancer metastasis can show upward mesenteric spread and lateral extramesenteric spread along the internal iliac vessels. Based on the rationale of lateral extramesenteric spread, lateral pelvic lymph node dissection (LPLND) is performed to eradicate LPLN metastasis in patients with rectal cancer located at or below the peritoneal reflection[3-9].

The management of LPLN associated with low rectal cancer differs considerably between Western countries and Japan. In Western countries, LPLN metastasis is generally considered as a metastatic disease, and preoperative chemoradiation and total mesorectal excision (TME) is the standard treatment[10]. In contrast, LPLN metastasis is regarded as a local disease in Japan, and TME with LPLND is performed for patients with locally advanced low rectal cancer[11]. Large-scale retrospective studies in Japan evaluated the survival outcome of patients with LPLN metastasis, and concluded that LPLN could be considered as regional lymph nodes in low rectal cancer[12].

LPLN metastasis was identified in approximately 20% of Japanese patients with T3 or T4 tumors who underwent LPLND[11,13]. Nevertheless, the clinical significance of LPLND has not been fully proven and a prospective study is needed to resolve whether LPLND has any survival benefit in patients with low rectal cancer. Accordingly, a randomized controlled trial was conducted to clarify the clinical significance of prophylactic LPLND for clinical stage II and III low rectal cancer (JCOG0212)[14]. However, to date, no studies have addressed the surgical outcome of TME with LPLND for stage IV low rectal cancer, and the clinical significance of LPLND for stage IV low rectal cancer is still unclear.

We retrospectively evaluated 50 consecutive stage IV low rectal cancer patients without clinical LPLN metastasis to assess the survival benefit of prophylactic LPLND in patients with stage IV low rectal cancer. We analyzed various prognostic factors including LPLND with respect to overall survival (OS), and evaluated cumulative local recurrence of patients with LPLND.

We selected patients from our colorectal cancer databases with stage IV low rectal cancer according to the AJCC 7th edition[15], applied the following inclusion criteria: Adenocarcinoma confirmed on histological examination, preoperative pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan negative for clinical LPLN metastasis, and primary tumor resection undertaken at Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital or Niigata Cancer Center Hospital between January 2000 and December 2015. We selected 71 consecutive stage IV low rectal cancer patients who underwent primary tumor resection, and enrolled 50 of these 71 patients without clinical LPLN metastasis (Figure 1, Table 1). All the patients had negative circumferential resection margin. Twenty of these 71 patients were excluded in the present study because they were diagnosed as positive for clinical LPLN metastasis by preoperative pelvic CT scan, and 1 patient was excluded because of loss of follow-up. Clinical LPLN metastasis was defined as LN with a maximum diameter of 10 mm or more on preoperative pelvic CT scan. In this study period, “therapeutic LPLND” was carried out for patients with clinical LPLN metastasis. For patients without clinical LPLN metastasis, whether “prophylactic LPLND” was performed or not was determined by preoperative conference. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NACRT) was not administered at the participating institutions because it is uncertain whether this approach improves OS[16,17]. Distant metastasis was classified according to the JSCCR classification[18]. Liver metastases were classified into three categories (H1: 1-4 metastatic tumors all of maximum diameter 5 cm or less; H2: Those other than H1 or H3; H3: 5 or more metastatic tumors at least one of which has a maximum diameter of more than 5 cm). Lung metastases were classified into three categories (LM1: Metastasis limited to one lobe; LM2: Metastasis to more than one lobe in one side of lung; LM3: Metastasis to both sides of lungs). Peritoneal metastases were classified into three categories (P1: Metastasis localized to adjacent peritoneum; P2: Metastasis limited to distant peritoneum; P3: Diffuse metastasis to distant peritoneum). This retrospective study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Niigata University approved the study protocol (approval number: 2330), waiving patient consent.

| Variable | |

| Age (yr)1 | 58.5 (31-78) |

| Sex | |

| Male:female | 43:7 |

| Preoperative CEA level (ng/mL)1 | 24.5 (1.6–6856.5) |

| Tumor size (mm)1 | 63.0 (22–130) |

| T category | |

| T2:T3:T4 | 2:31:17 |

| Histopathological grading | |

| G1:G2:G3 | 1:35:14 |

| Lymphatic invasion | |

| Absence:Presence | 6:44 |

| Venous invasion | |

| Absence:Presence | 10:40 |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| Absence:Presence | 9:41 |

| Pathological LPLN metastasis | |

| Absence:Presence | 15:12 |

| No. of metastatic organs | |

| 1:2:3 | 44:5:1 |

| Metastatic organ | |

| Liver:Lung:Peritoneum:Paraaortic LN:Bone | 28:16:10:1:2 |

| Grade of liver metastasis2 | |

| H1:H2:H3 | 14:5:9 |

| Grade of lung metastasis2 | |

| LM1:LM2:LM3 | 8:7:1 |

| Grade of peritoneal metastasis2 | |

| P1:P2:P3 | 8:1:1 |

| Grade ≥ 3 Complication of primary tumor resection | |

| Absence:Presence | 38:12 |

| Residual tumor status | |

| R0:R2 | 20:30 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | |

| Absence:Presence | 41:9 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |

| Absence:Presence | 7:43 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | |

| 5FU-LV and/or S-1 and/or capecitabine | 25 |

| FOLFOX and/or CapeOX and/or FOLFIRI | 33 |

| Bevacizumab | 18 |

| Cetuximab or panitumumab | 4 |

Twenty-three patients underwent only TME (“TME group”), and 27 patients underwent TME with LPLND (“LPLND group”). Regarding LPLND, 26 procedures were performed as open surgery and 1 procedure was done as laparoscopic surgery. The LPLN were classified into five areas (distal internal iliac, proximal internal iliac, obturator, external iliac and common iliac) according to the JSCCR classification[18]. In the LPLND group, LPLND was carried out in accordance with previously reported methods[3,13,14]. Bilateral LPLND was performed simultaneously with primary tumor resection in LPLND group. Post-operative complications were monitored for 90 d after surgery and graded according to a standard classification[19]. Major complications were defined as grade ≥ 3.

To achieve R0 resection of metastatic lesion, simultaneous or staged metastasectomy was planned according to the patients’ condition. Essentially, simultaneous metastasectomy was performed when the patients had resectable intra-abdominal metastasis such as solitary liver metastasis which could be respected by partial hepatectomy, limited peritoneal dissemination, or paraaortic lymph nodes. Staged metastasectomy was planned when the patients had extra-abdominal metastasis such as lung metastasis, or liver metastasis which needed major hepatectomy such as right hepatic lobectomy. In this cohort, there were no patients who received conversion therapy such as hepatectomy for initially unresectable multiple liver metastasis. We classified the patients according to residual tumor status, i.e., the patients who received R0 resection of both primary lesion and distant metastasis were classified as “R0”, and the other patients in whom R0 resection could not be achieved were classified as “R2”.

We evaluated possible prognostic factors including LPLND for OS, and compared cumulative local recurrence rates between the TME and LPLND groups. To elucidate the factors influencing OS after surgery, 16 variables were tested in all 50 patients: Age (< 65 vs ≥ 65 years), sex, preoperative Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level (< 20 ng/mL vs ≥ 20 ng/mL), tumor size (< 60 mm vs ≥ 60 mm), T category (T2, 3 vs T4), histopathological grading (G1, 2 vs G3), lymphatic invasion (absence vs presence), venous invasion (absence vs presence), lymph node metastasis (absence vs presence), LPLND (absence vs presence), number of metastatic organs (1 vs 2), metastatic organ (liver only vs others), Grade 3 complication of primary tumor resection (absence vs presence), residual tumor status (R0 vs R2), Preoperative chemotherapy (absence vs presence), and Postoperative chemotherapy (absence vs presence).

After the operation, the patients were followed-up by physical examination, laboratory testing, and imaging. CEA and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were monitored periodically. Disease recurrence and tumor progression were determined mainly by chest-abdominal-pelvic CT scans. Colonoscopy was performed to detect local recurrence at the anastomotic site. The median follow-up period of all 50 patients was 23.6 mo (range: 1-130). Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The relationships between each of the clinicopathological variables and residual tumor status were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Five-year OS and cumulative local recurrence rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess for significant difference between the subgroups by univariate analysis. To investigate independent prognostic factors for OS, factors with a P value of less than 0.10 in univariate analyses were entered into multivariate analysis. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to identify factors that were independently associated with OS after surgery. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All patients received R0 resection of primary site with the operative procedure as follows: 31 patients received low anterior resection, 18 patients received abdominoperineal resection, 1 patient received pelvic exenteration. Dysuria was observed in 20 patients, and all of them were grade 1 or 2. Major complications (grade ≥ 3) were observed in 12 of 50 patients (24.0%); anastomotic leakage, surgical site infection, and anastomotic stenosis were observed in 4, 7, and 1 patients, respectively. Postoperative histopathological analysis revealed LPLN metastasis in 12 of 27 patients (44.4%) who received prophylactic LPLND, with a median number of 1 metastatic node per patient (range: 1-4). The sites of LPLN metastases were as follows: distal internal iliac nodes, proximal internal iliac nodes, obturator nodes, external iliac nodes, and common iliac nodes in 6, 5, 3, 1, and 1 patients, respectively.

Of the 50 patients, 24 received metastasectomy and 20 received R0 resection of both primary and metastatic sites (Figure 1). Sixteen patients simultaneously underwent primary tumor resection and metastasectomy. The details of the metastasectomy sites are as follows: Liver in 8 patients, limited peritoneal dissemination in 7 patients, and liver and paraaortic lymph node in 1 patient. Successful R0 resection was achieved in 14 of 16 patients; however, two patients who had liver and lung metastases underwent only hepatectomy because of progression of lung tumor after hepatectomy. In contrast, 8 patients underwent staged metastasectomy after primary tumor resection. The details of the metastasectomy sites are as follows: Liver in 4 patients, lung in 3 patient, liver and lung in 1 patient. R0 resection was achieved in 6 of these 8 patients; however, 1 patient who had liver and lung metastases underwent only hepatectomy because of progression of lung tumor after hepatectomy, and 1 patient who had lung metastasis underwent margin positive surgery. In contrast, 26 of 50 patients did not undergo metastasectomy because of tumor progression or development of new metastatic lesions after primary tumor resection.

A comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between the LPLND and TME groups showed that there were no significant differences in 15 tested variables (Table 2). Five-year overall cumulative survival rates after primary tumor resection were 74.0% at 1 year, 43.7% at 3 years, and 23.4% at 5 years. Univariate analyses revealed that the LPLND group showed no significant benefit compared with TME group (28.7% vs 17.0%, P = 0.523) (Table 3 and Figure 2), and that age (≥ 65 years) and R0 resection were factors whose P values were less than 0.10 for OS. Multivariate analysis identified R0 resection as significant independent prognostic factor for OS (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Variable | TME group (n = 23) | LPLND group (n = 27) | P value |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 65 | 13 | 19 | 0.382 |

| ≥ 65 | 10 | 8 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 20 | 23 | 0.999 |

| Female | 3 | 4 | |

| Preoperative CEA level (ng/mL) | |||

| < 20 | 10 | 11 | 0.999 |

| ≥ 20 | 13 | 16 | |

| Tumor size (mm) | |||

| < 60 | 7 | 8 | 0.999 |

| ≥ 60 | 16 | 19 | |

| T category | |||

| T2, 3 | 11 | 14 | 0.999 |

| T4 | 12 | 13 | |

| Histopathological grading | |||

| G1, 2 | 19 | 17 | 0.206 |

| G3 | 4 | 10 | |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||

| Absence | 3 | 3 | 0.999 |

| Presence | 20 | 24 | |

| Venous invasion | |||

| Absence | 7 | 3 | 0.155 |

| Presence | 16 | 24 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Absence | 7 | 2 | 0.062 |

| Presence | 16 | 25 | |

| No. of metastatic organs | |||

| 1 | 21 | 23 | 0.647 |

| 2, 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| Metastatic organ | |||

| Liver only | 12 | 13 | 0.999 |

| Others | 11 | 14 | |

| Grade ≥ 3 complication of primary tumor resection | |||

| Absence | 17 | 21 | 0.999 |

| Presence | 6 | 6 | |

| Residual tumor status | |||

| R0 | 8 | 12 | 0.569 |

| R2 | 15 | 15 | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | |||

| Absence | 18 | 23 | 0.715 |

| Presence | 5 | 4 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |||

| Absence | 4 | 3 | 0.689 |

| Presence | 19 | 24 |

| Variable | Modality | n | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| 5-yr OS (%) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Age (yr) | < 65 | 32 | 27.9 | 0.095 | 1 | |

| ≥ 65 | 18 | 14.8 | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 0.197 | ||

| Sex | Male | 43 | 19.8 | 0.618 | ||

| Female | 7 | 42.9 | ||||

| Preoperative CEA level (ng/mL) | < 20 | 21 | 23.7 | 0.671 | ||

| ≥ 20 | 29 | 22.9 | ||||

| Tumor size (mm) | < 60 | 15 | 29.6 | 0.634 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 35 | 20.9 | ||||

| T category | T2, 3 | 25 | 17.3 | 0.515 | ||

| T4 | 25 | 32.5 | ||||

| Histopathological grading | G1, 2 | 36 | 25 | 0.348 | ||

| G3 | 14 | 21.4 | ||||

| Lymphatic invasion | Absence | 6 | 0 | 0.446 | ||

| Presence | 44 | 24.2 | ||||

| Venous invasion | Absence | 10 | 40 | 0.215 | ||

| Presence | 40 | 19.1 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | Absence | 9 | 0 | 0.904 | ||

| Presence | 41 | 27.5 | ||||

| LPLND | Absence | 23 | 17 | 0.523 | ||

| Presence | 27 | 28.7 | ||||

| No. of metastatic organs | 1 | 44 | 23.8 | 0.866 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 22.2 | ||||

| Metastatic organ | Liver only | 25 | 36 | 0.241 | ||

| Others | 25 | 10.6 | ||||

| Grade ≥ 3 complication of primary tumor resection | Absence | 38 | 28.8 | 0.398 | ||

| Presence | 12 | 9.5 | ||||

| Residual tumor status | R0 | 20 | 59 | < 0.001 | 1 | |

| R2 | 30 | 3.6 | 2.1 (1.4–3.0) | < 0.001 | ||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | Absence | 41 | 17.6 | 0.254 | ||

| Presence | 9 | 55.6 | ||||

| Postoperative chemotherapy | Absence | 7 | 38.1 | 0.397 | ||

| Presence | 43 | 24.3 | ||||

Five of the 50 patients showed local recurrence. The details of local recurrence sites are as follows: Anastomotic site in 2 patients, and the other intrapelvic space in 3 patients. One patient who had LPLND showed local recurrence of the right LPLN area. Twenty-seven patients with LPLND showed no significantly improved 5-year cumulative local recurrence rate compared with the 23 patients without LPLND (21.4% vs 14.8%, P = 0.833) (Figure 3).

In the present study, we showed that prophylactic LPLND was not a significant prognostic factor for OS and did not contribute to local control. These results suggest that prophylactic LPLND is not an important component of surgical treatment in stage IV low rectal cancer.

It is possible that there are several acceptable treatment strategies in stage IV low rectal cancer patients without clinical LPLN metastasis. When the primary and metastatic sites are resectable, the patient can be treated with a staged or simultaneous resection to achieve R0 resection of both primary and metastatic sites. To achieve R0 resection of the primary site, the options are: (1) TME only; (2) TME with LPLND; (3) NAC followed by TME; and (4) NACRT followed by TME, etc. However, optimal treatment of patients with primary metastatic rectal cancer is controversial[20,21].

The NCCN guidelines state that NACRT is a standard treatment for stage II/III rectal cancer[10], however, it is also associated with increased toxicity (e.g., radiation-induced injury, hematological toxicities). To date, the clinical significance of NACRT for stage IV low rectal cancer remains still unclear. van Dijk et al[20] reported that radical surgical treatment of all tumor sites carried out after short-course radiotherapy, and bevacizumab-capecitabine-oxaliplatin combination therapy is a feasible and potentially curative approach in primary metastasized rectal cancer. Conversely, Butte et al[21] reported that selective exclusion of radiotherapy may be considered in rectal cancer patients who are diagnosed with simultaneous liver metastasis, because systemic sites were overwhelmingly more common than pelvic recurrences after primary tumor resection. In stage IV patients, we surmised that subsequent metastasectomy and systemic chemotherapy are essential for cure; hence, a treatment strategy without NACRT could be a reasonable and acceptable approach to avoid the toxicity associated with NACRT.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report regarding the clinical significance of prophylactic LPLND in stage IV low rectal cancer patients without clinical LPLN metastasis. We demonstrated that prophylactic LPLND has no oncological benefits regarding OS and cumulative local recurrence in this setting. Previous studies reported that TME with LPLND is associated with significant morbidity, longer operative time, greater blood loss, and functional impairment, particularly impotence and bladder dysfunction[3,12-25]. To avoid the post-operative complications associated with LPLND and achieve early induction of postoperative chemotherapy, we think that prophylactic LPLND could be omitted for stage IV low rectal cancer patients without clinical LPLN metastasis.

We recognize several limitations in this study. First, this retrospective study included a small sample size. Second, we could not investigate how many patients, such as those who had multiple distant metastases, were excluded from the indications for primary tumor resection, because those patients were generally not referred to surgeons. Third, we could not investigate detailed parameters such as resectability criteria of distant metastases, comorbidity and response to chemotherapy. Fourth, it is possible that the LPLND group included patients with suspicious clinical LPLN metastasis of maximum diameter less than 10 mm, because histopathological LPLN metastases were observed in 12 of 27 patients (44.4%) patients in the LPLND group. Fifth, we included only patients without clinical LPLN metastasis. Hence, we could not assess the value of therapeutic LPLND for patients with clinical LPLN metastasis, and the clinical significance of LPLND for these patients is still unclear. In future, a multicenter prospective study is required to clarify the clinical significance of LPLND for stage IV low rectal cancer patients.

In conclusion, prophylactic LPLND shows no oncologic benefits in patients with stage IV low rectal cancer without clinical LPLN metastasis.

No studies have addressed the surgical outcome of total mesorectal excision with lateral pelvic lymph node dissection (LPLND) for stage IV low rectal cancer, and the clinical significance of LPLND for stage IV low rectal cancer is still unclear.

There is little clinical information relating to LPLND for stage IV low rectal cancer.

This study is the first report regarding the clinical significance of prophylactic LPLND in stage IV low rectal cancer patients without clinical LPLN metastasis.

Prophylactic LPLND shows no oncologic benefits in patients with stage IV low rectal cancer without clinical LPLN metastasis.

To assess the clinical significance of prophylactic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection is the first research in stage IV low rectal cancer. The article is well-designed and important for clinical practice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dirier A, Palacios-Eito A, Surlin VM S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Appleby LH, Deddish MR. Discussion on the treatment of advanced cancer of the rectum. Proc R Soc Med. 1950;43:1071-1081. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Heald RJ, Moran BJ. Embryology and anatomy of the rectum. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;15:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Moriya Y, Hojo K, Sawada T, Koyama Y. Significance of lateral node dissection for advanced rectal carcinoma at or below the peritoneal reflection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:307-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Min BS, Kim JS, Kim NK, Lim JS, Lee KY, Cho CH, Sohn SK. Extended lymph node dissection for rectal cancer with radiologically diagnosed extramesenteric lymph node metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3271-3278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Akasu T, Sugihara K, Moriya Y. Male urinary and sexual functions after mesorectal excision alone or in combination with extended lateral pelvic lymph node dissection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2779-2786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim TH, Jeong SY, Choi DH, Kim DY, Jung KH, Moon SH, Chang HJ, Lim SB, Choi HS, Park JG. Lateral lymph node metastasis is a major cause of locoregional recurrence in rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:729-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ueno M, Oya M, Azekura K, Yamaguchi T, Muto T. Incidence and prognostic significance of lateral lymph node metastasis in patients with advanced low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:756-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takahashi T, Ueno M, Azekura K, Ohta H. Lateral node dissection and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:S59-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yano H, Saito Y, Takeshita E, Miyake O, Ishizuka N. Prediction of lateral pelvic node involvement in low rectal cancer by conventional computed tomography. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1014-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology-rectal cancer (Version 2). 2016; Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. |

| 11. | Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hyodo I, Igarashi M, Ishida H. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) Guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:207-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Akiyoshi T, Watanabe T, Miyata S, Kotake K, Muto T, Sugihara K; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Results of a Japanese nationwide multi-institutional study on lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis in low rectal cancer: is it regional or distant disease? Ann Surg. 2012;255:1129-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sugihara K, Kobayashi H, Kato T, Mori T, Mochizuki H, Kameoka S, Shirouzu K, Muto T. Indication and benefit of pelvic sidewall dissection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1663-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fujita S, Akasu T, Mizusawa J, Saito N, Kinugasa Y, Kanemitsu Y, Ohue M, Fujii S, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after mesorectal excision with and without lateral lymph node dissection for clinical stage II or stage III lower rectal cancer (JCOG0212): results from a multicentre, randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:616-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer 2010; . |

| 16. | Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Putter H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, van Krieken JH. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3104] [Cited by in RCA: 3116] [Article Influence: 129.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huh JW, Kim HC, Park HC, Choi DH, Park JO, Park YS, Park YA, Cho YB, Yun SH, Lee WY. Is Chemoradiotherapy Beneficial for Stage IV Rectal Cancer? Oncology. 2015;89:14-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese classification of colorectal carcinoma. 2nd English ed. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara Co 2009; . |

| 19. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24776] [Article Influence: 1179.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Dijk TH, Tamas K, Beukema JC, Beets GL, Gelderblom AJ, de Jong KP, Nagtegaal ID, Rutten HJ, van de Velde CJ, Wiggers T. Evaluation of short-course radiotherapy followed by neoadjuvant bevacizumab, capecitabine, and oxaliplatin and subsequent radical surgical treatment in primary stage IV rectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1762-1769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Butte JM, Gonen M, Ding P, Goodman KA, Allen PJ, Nash GM, Guillem J, Paty PB, Saltz LB, Kemeny NE. Patterns of failure in patients with early onset (synchronous) resectable liver metastases from rectal cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5414-5423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yano H, Moran BJ. The incidence of lateral pelvic side-wall nodal involvement in low rectal cancer may be similar in Japan and the West. Br J Surg. 2008;95:33-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hojo K, Sawada T, Moriya Y. An analysis of survival and voiding, sexual function after wide iliopelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with carcinoma of the rectum, compared with conventional lymphadenectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Michelassi F, Block GE. Morbidity and mortality of wide pelvic lymphadenectomy for rectal adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1143-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Enker WE. Potency, cure, and local control in the operative treatment of rectal cancer. Arch Surg. 1992;127:1396-1401; discussion 1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |