Published online Jun 10, 2017. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i3.293

Peer-review started: September 9, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: February 25, 2017

Accepted: March 16, 2017

Article in press: March 17, 2017

Published online: June 10, 2017

Processing time: 267 Days and 7.6 Hours

Among the three grades of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), the prognosis for Grade 1 (G1) with surgery is very good. Therefore, we evaluated the prognoses of pancreatic NET (PNET) G1 patients without surgery. A total of 8 patients who were diagnosed with NET G1, with an observation period of more than 6 mo until surgery or without surgery, were recruited. The patients who underwent surgery were ultimately diagnosed using specimens obtained during the surgery, whereas the patients who did not undergo surgery were diagnosed using specimens obtained by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration. Overall, we mainly evaluated the observation period and tumor growth. The observation period for the five cases with surgery ranged from 6-80 mo, and tumor growth was observed in one case. In contrast, the observation period for the three cases without surgery ranged from 17-54 mo, and tumor growth was not observed. Therefore, although the first-choice treatment for NETs is surgery, our experience includes certain NET G1 patients who were followed up without surgery.

Core tip: We evaluated the prognoses of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor Grade 1 (NET G1) patients without surgery. A total of 8 patients who were diagnosed with NET G1, with an observation period of more than 6 mo until surgery or without surgery, were recruited. The observation period for the five cases with surgery ranged from 6-80 mo, and tumor growth was observed in one case. In contrast, the observation period for the three cases without surgery ranged from 17-54 mo, and tumor growth was not observed. Our experience thus includes certain NET G1 patients who were followed up without surgery.

- Citation: Sugimoto M, Takagi T, Suzuki R, Konno N, Asama H, Watanabe K, Nakamura J, Kikuchi H, Waragai Y, Takasumi M, Kawana S, Hashimoto Y, Hikichi T, Ohira H. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor Grade 1 patients followed up without surgery: Case series. World J Clin Oncol 2017; 8(3): 293-299

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v8/i3/293.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v8.i3.293

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the digestive organs are classified as Grade 1 (G1) or Grade 2 (G2) or as neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 classification, which is based on cellular proliferative potential (Ki-67 index and the mitotic count)[1]. Generally speaking, pancreatic NETs (PNETs) are a rare condition, accounting for only 2%-5% of pancreatic tumors[2]. However, reports about PNETs have been increasing in direct proportion to more detailed diagnostic imaging.

Among the three grades of NETs, the prognosis for G1 is very good. It has been reported that the two-year progression-free survival rate for NET G1 is 92%[3] and that the two-year survival rate is 100%[4]. Five-year survival was reported to be 55.7% by Zeng et al[5] and 82.6% by Yang et al[6]. In other reports, however, the five-year survival rate was 90% or more[4,7-10].

Regarding PNET treatment, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network[11], the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society[12], and the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society[13] have established guidelines. The first-choice treatment is surgery for all grades of PNETs if the lesions are resectable.

Regarding diagnosing NETs before surgery, the efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has been reported[14-17]. As mentioned above, the first-choice treatment for resectable PNETs is surgery. However, if a patient is diagnosed with NET G1 based on the Ki-67 index of an EUS-FNA specimen, there is a possibility that the patient will not agree to surgery because of a good prognosis.

Accordingly, we examined the following two topics in this report: (1) the prognoses of NET G1 diagnosed by EUS-FNA without surgery; and (2) the tumor growth of NET G1 from diagnosis until surgery.

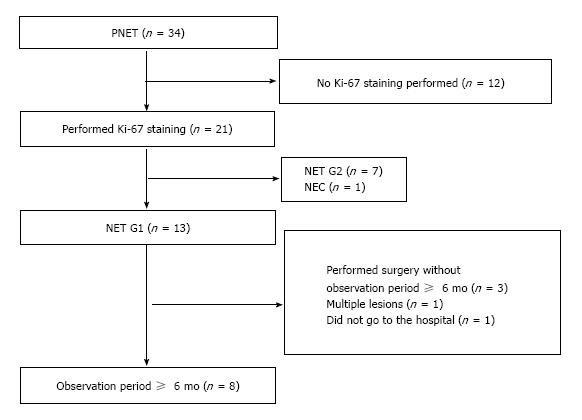

A total of 34 patients were diagnosed with PNETs from February 2001 to December 2015. Among these patients, 21 underwent measurement of the Ki-67 index using specimens obtained by EUS-FNA or surgery (Figure 1). Thirteen patients were diagnosed with NET G1, seven patients were diagnosed with NET G2, and one patient was diagnosed with NEC. We recommended surgery for the NET patients, regardless of their WHO 2010 classification. However, if a patient did not agree to surgery, we only performed a follow-up. We focused on eight NET G1 patients who waited for surgery for no less than six months or who were followed up for no less than six months without surgery. The observation period was defined as no less than 6 mo based on a report on everolimus by Yao et al[18]. In that report, the length of progression-free survival of the placebo group was 5.4 mo.

The patients who underwent surgery were ultimately diagnosed using specimens obtained during surgery, and the patients who did not undergo surgery were diagnosed using specimens obtained by EUS-FNA. UCT260, GF-UCT240-AL5, or GF-UC240P (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), was used as the echoendoscope, and EU-ME1 or EU-ME2 (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) was used as the ultrasonography diagnostic device. EchoTip 19 or 22 or 25G (Cook Medical Inc., NC, United States), and EZ Shot 22G (Olympus Medical Systems) and Expect 22G (Boston Scientific, MA, United States) were used as the aspiration needles.

All patients underwent echoendoscope insertion under sedation with midazolam. After we drew the target on the monitor and checked that no blood flow was present in the aspiration line, we punctured the target, passing through the gastric or duodenal wall. We excluded the stylet of the needle and connected a syringe with 10-20 mL negative pressure to the edge of the needle. We then moved the needle back and forth 20 times within the lesion. In particular, we moved the needle to multiple locations within the target (this has been reported as the “fanning method”)[19]. After we terminated the negative pressure, we removed the needle. The EUS-FNA sample was then placed on a glass slide, and the specimen was preserved in 15% formalin for histological diagnosis. All other samples were stained using Cyto-Quick. We observed the samples to assess whether a sufficient number of cells were sampled (rapid on-site cytological evaluation, or ROSE)[20]. If a sample was sufficient, we halted the EUS-FNA; if a sample was not sufficient, we performed another aspiration. The samples obtained for histological diagnosis were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and were also immunostained for the following: Ki-67, chromogranin, synaptophysin (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), and CD56 (ZYMED, Carlsbad, CA, United States). The grades of the PNET cases were determined based on the Ki-67 index outlined in the WHO 2010 classification. The grades of the specimens obtained during surgery were also determined based on the Ki-67 index and the mitotic count, as defined in the WHO 2010 classification.

We reviewed each patient’s characteristics (sex, age, initial tumor size, and location of the tumor), the method of diagnosis (EUS-FNA or surgery), the Ki-67 index, the mitotic count, whether the patient was functional or not, tumor marker levels, observation period, and tumor growth. The observation period was determined as the number of months from tumor discrimination by abdominal echo or computed tomography (CT) until the tumors were resected. For the patients without surgery, the observation period was determined as the number of months from tumor discrimination by abdominal echo or CT until the tumors were recognized by a final abdominal echo or CT. The patients specifically underwent dynamic CT or abdominal echo approximately 2 times per year, performed by an attending physician.

The age range of the patients was 41-81 years, and the patient group included two males and six females (Table 1). The initial major tumor axes ranged from 3-40 mm. The locations of the tumors were the pancreatic head (n = 3), pancreatic body (n = 3), and pancreatic tail (n = 2). Five patients underwent surgery, and three patients did not but did undergo EUS-FNA. The Ki-67 index ranged from 0.4%-1.3% (five patients did not undergo precise measurement, but their index was < 2.0%). The mitotic count of the specimens obtained during surgery was 0-2/10 HPFs. Three patients were functional (1 with a growth hormone-producing tumors, 1 with a glucagonoma, and 1 with an insulinoma). AFP, NSE, CEA or CA19-9 was also measured, but these tumor markers were not elevated in any of the patients.

| Sex | Age (yr) | Initial size (mm) | Location of tumor | Method of final diagnosis | Ki-67 index (%) | Mitotic count (/10 HPFs) | Function | Elevated tumor markers | Observation period (mo) | Tumor growth (mm) | |

| 1 | F | 79 | 19 | Body | Surgery | < 2.0 | 0 | No | No | 6 | No |

| 2 | F | 41 | 34 | Tail | Surgery | 0.9 | 2 | Yes | No | 80 | 76 |

| 3 | M | 69 | 3 | Body | Surgery | < 2.0 | 0 | Yes | No | 15 | No |

| 4 | M | 55 | 40 | Head | Surgery | < 1.0 | 0 | Yes | No | 6 | No |

| 5 | F | 73 | 32 | Head | Surgery | 1.3 | 0 | No | No | 9 | No |

| 6 | F | 81 | 4 | Head | EUS-FNA | < 1.0 | Difficult | No | No | 22 | No |

| 7 | F | 64 | 8 | Tail | EUS-FNA | 0.4 | Difficult | No | No | 17 | No |

| 8 | F | 70 | 8 | Body | EUS-FNA | < 1.0 | Difficult | No | No | 54 | No |

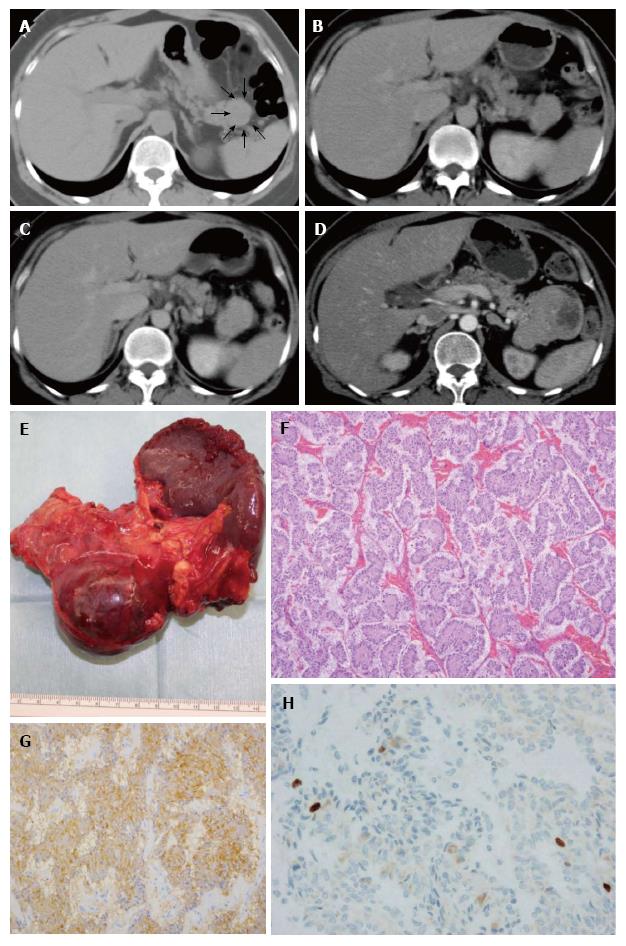

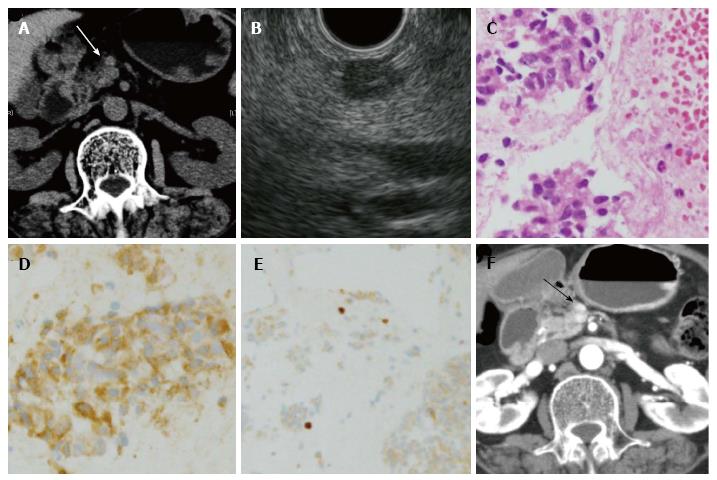

The observation periods ranged from 6-80 mo for patients 1-4. Only patient 2 was observed to exhibit tumor growth (Figure 2). In contrast, the observation periods for the three cases without surgery ranged from 17-54 mo, and all three cases did not show tumor growth. Among these three cases, one case is shown in Figure 3.

In this report, we examined whether we could follow up NET G1 without surgery. Among eight patients who were observed before surgery for no less than six months or who did not undergo surgery for at least six months, tumor growth was observed in one patient.

As described above, the prognoses of the NET G1 were very good. However, the data were relevant to prognoses only after surgery. Sadot et al[21] reported the prognoses of 104 PNET patients who were diagnosed pathologically or by imaging. In that report, the diameters of all PNET lesions were smaller than 3.0 cm. Among the patients, 26 did not undergo surgery; those without surgery who were only followed up did not exhibit tumor growth or metastases to other organs. Though cases diagnosed by only imaging were included in that report, certain PNET patients could be followed up without surgery. Additionally, Shin et al[22] reported 72 gastroenteropancreatic NET cases with liver metastases. Among these cases, 12 were NET G1 (17%). Zerbi et al[23] reported that 16.1% of NET G1 showed metastases to the lymph nodes and that 12.6% of NET G1 showed liver metastases. In addition, Gaujoux et al[24] reported 20 PNET G1 cases with liver metastases. In the present report, one case exhibited tumor growth in the observation period. Therefore, we have to follow up NET G1 while taking the risk factors for metastases and tumor growth into consideration.

What are the specific risk factors for NETs? In the past reports, nonfunction and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and jaundice were reported to be risk factors for liver metastases. Moreover, Tao et al[25] reported that elevated tumor markers (AFP, CEA, CA125, CA19-9) were predictive factors for liver metastases or lymph node metastases, and Jiang et al[26] reported that a tumor diameter larger than 25 mm was a risk factor for lymph node metastases. In the present report, the lesion diameters of 3 cases were larger than 25 mm; the patients were numbered 2, 4, and 5 (Table 1). Though patients 4 and 5 underwent surgery six months after diagnosis, the lesion of patient 2 grew from 34 to 76 mm in diameter. Though past studies involved not only NET G1 but also other grades of NETs, the risk factors cited in these past reports were considered to be important to determine follow-up without surgery.

In this report, there were certain limitations. First, the research was retrospectively performed at a single institution, and a small number of patients were included. More patients will be needed for more conclusive research. Second, the followed-up patients were diagnosed only by EUS-FNA. However, a high accordance rate between specimens obtained during surgery and specimens obtained by EUS-FNA was reported in past studies[14-17], and for NET G1, the accordance rate between specimens obtained during surgery and specimens obtained by EUS-FNA was 92.3% (36/39)[14-17] (Larghi, 2012 #59). We believe that we relatively correctly judged the grading based on the Ki-67 index of NET G1. Third, mitotic counts were not measured in EUS-FNA specimens. Therefore, surgery is desirable as a treatment for NETs. Fourth, we did not measure several of the tumor markers described above. Rossi et al[27] reported the efficacy of plasma chromogranin A as a predictive factor for NET progression; this should be studied further in the future.

The first-choice treatment for NETs is absolutely surgery. However, our experience includes certain patients who were followed up without surgery because of a lack of consent for surgery.

We thank all the staff in the Department of Gastroenterology, Fukushima Medical University; the Department of Endoscopy, Fukushima Medical University Hospital; and the ward on the 8th west floor of Fukushima Medical University Hospital as well as American Journal Experts, an English-language proofreading company.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor Grade 1 (PNET G1) patients who were followed for more than six months before surgery or who were followed up without surgery for more than six months.

PNETs were diagnosed using specimens obtained by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) or obtained during surgery.

Metastatic pancreatic tumors, accessory spleen, acinar cell carcinoma, paraganglioma.

All tumor markers were not elevated.

PNETs are pancreatic tumors that are strongly enhanced on contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

Spindle-shaped tumor cells were observed. The tumor cells formed funicular lines and were positive for immunostaining of chromogranin A.

Surgery or follow-up.

The prognosis of PNET G1 is very good. However, certain PNET G1 patients exhibit metastases. Therefore, the first-choice treatment for resectable NETs is surgery.

EUS: A technique in which an echoendoscope is used to enable observation of the chest and abdominal organs, namely, the esophagus, stomach or duodenum; EUS-FNA: A technique used to obtain specimens from chest and abdominal lesions by aspiration under EUS guidance.

The gold standard of treatment for NET G1 is surgery. However, if patients are diagnosed with NET G1 by EUS-FNA, there is a possibility that the patients will not agree to surgery. In fact, certain NET G1 patients did not agree to surgery in the current case series, so the authors only followed up these patients. If we only follow up PNET G1 patients, the authors have to be careful about certain risk factors for metastasis of the PNETs.

This is an interesting paper on whether patients with G1 pancreatic NET can be followed without surgery using a case series of patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: He SQ, Kleeff J, Shiryajev YN, Somani P, Tsoulfas G S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2010; . |

| 2. | Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063-3072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3022] [Cited by in RCA: 3246] [Article Influence: 190.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cho JH, Ryu JK, Song SY, Hwang JH, Lee DK, Woo SM, Joo YE, Jeong S, Lee SO, Park BK. Prognostic Validity of the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the European Neuroendocrine Tumors Staging Classifications for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Retrospective Nationwide Multicenter Study in South Korea. Pancreas. 2016;45:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pape UF, Jann H, Müller-Nordhorn J, Bockelbrink A, Berndt U, Willich SN, Koch M, Röcken C, Rindi G, Wiedenmann B. Prognostic relevance of a novel TNM classification system for upper gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2008;113:256-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zeng YJ, Liu L, Wu H, Lai W, Cao JZ, Xu HY, Wang J, Chu ZH. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: analysis from a single-institution. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5775-5781. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yang M, Tian BL, Zhang Y, Su AP, Yue PJ, Xu S, Wang L. Evaluation of the World Health Organization 2010 grading system in surgical outcome and prognosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2014;43:1003-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lewkowicz E, Trofimiuk-Müldner M, Wysocka K, Pach D, Kiełtyka A, Stefańska A, Sowa-Staszczak A, Tomaszewska R, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a 10-year experience of a single center. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2015;125:337-346. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yang M, Zeng L, Zhang Y, Su AP, Yue PJ, Tian BL. Surgical treatment and clinical outcome of nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a 14-year experience from one single center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang YH, Lin Y, Xue L, Wang JH, Chen MH, Chen J. Relationship between clinical characteristics and survival of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A single-institution analysis (1995-2012) in South China. BMC Endocr Disord. 2012;12:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shiba S, Morizane C, Hiraoka N, Sasaki M, Koga F, Sakamoto Y, Kondo S, Ueno H, Ikeda M, Yamada T. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A single-center 20-year experience with 100 patients. Pancreatology. 2016;16:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Neuroendocrine tumors. 2011; Available from: http://www.nccn.org/. |

| 12. | Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, de Herder WW, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, Marx SJ, Pasieka JL, Pommier RF, Yao JC. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010;39:735-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Steinmüller T, Kianmanesh R, Falconi M, Scarpa A, Taal B, Kwekkeboom DJ, Lopes JM, Perren A, Nikou G, Yao J. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with liver metastases from digestive (neuro)endocrine tumors: foregut, midgut, hindgut, and unknown primary. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:47-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Larghi A, Capurso G, Carnuccio A, Ricci R, Alfieri S, Galasso D, Lugli F, Bianchi A, Panzuto F, De Marinis L. Ki-67 grading of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors on histologic samples obtained by EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:570-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hasegawa T, Yamao K, Hijioka S, Bhatia V, Mizuno N, Hara K, Imaoka H, Niwa Y, Tajika M, Kondo S. Evaluation of Ki-67 index in EUS-FNA specimens for the assessment of malignancy risk in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopy. 2014;46:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Unno J, Kanno A, Masamune A, Kasajima A, Fujishima F, Ishida K, Hamada S, Kume K, Kikuta K, Hirota M. The usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors based on the World Health Organization classification. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1367-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sugimoto M, Takagi T, Hikichi T, Suzuki R, Watanabe K, Nakamura J, Kikuchi H, Konno N, Waragai Y, Asama H. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor grading. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8118-8124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin EM, Van Cutsem E, Hobday TJ, Okusaka T, Capdevila J, de Vries EG. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:514-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2039] [Cited by in RCA: 2117] [Article Influence: 151.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bang JY, Magee SH, Ramesh J, Trevino JM, Varadarajulu S. Randomized trial comparing fanning with standard technique for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid pancreatic mass lesions. Endoscopy. 2013;45:445-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hikichi T, Irisawa A, Bhutani MS, Takagi T, Shibukawa G, Yamamoto G, Wakatsuki T, Imamura H, Takahashi Y, Sato A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid pancreatic masses with rapid on-site cytological evaluation by endosonographers without attendance of cytopathologists. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:322-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sadot E, Reidy-Lagunes DL, Tang LH, Do RK, Gonen M, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Kingham TP, Groot Koerkamp B, Untch BR. Observation versus Resection for Small Asymptomatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Matched Case-Control Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1361-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shin Y, Ha SY, Hyeon J, Lee B, Lee J, Jang KT, Kim KM, Park YS, Park CK. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors with Liver Metastases in Korea: A Clinicopathological Analysis of 72 Cases in a Single Institute. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:738-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zerbi A, Falconi M, Rindi G, Delle Fave G, Tomassetti P, Pasquali C, Capitanio V, Boninsegna L, Di Carlo V. Clinicopathological features of pancreatic endocrine tumors: a prospective multicenter study in Italy of 297 sporadic cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1421-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gaujoux S, Gonen M, Tang L, Klimstra D, Brennan MF, D’Angelica M, Dematteo R, Allen PJ, Jarnagin W, Fong Y. Synchronous resection of primary and liver metastases for neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4270-4277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tao M, Yuan C, Xiu D, Shi X, Tao L, Ma Z, Jiang B, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Wang H. Analysis of risk factors affecting the prognosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:2924-2928. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Jiang Y, Jin JB, Zhan Q, Deng XX, Shen BY. Impact and Clinical Predictors of Lymph Node Metastases in Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:3335-3344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rossi RE, Garcia-Hernandez J, Meyer T, Thirlwell C, Watkins J, Martin NG, Caplin ME, Toumpanakis C. Chromogranin A as a predictor of radiological disease progression in neuroendocrine tumours. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |