Published online Oct 10, 2016. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v7.i5.414

Peer-review started: February 28, 2016

First decision: July 5, 2016

Revised: August 19, 2016

Accepted: September 7, 2016

Article in press: September 9, 2016

Published online: October 10, 2016

Processing time: 225 Days and 2.4 Hours

To study the clinical findings and characteristic features in sciatic notch dumbbell tumors (SNDTs).

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical outcomes and characteristic features of consecutive cases of SNDTs (n = 8).

Buttock masses occurred in three patients with SNDT (37.5%). Severe buttock tenderness and pain at rest were observed in seven patients with SNDTs (87.5%). Remarkably, none of the patients with SNDTs experienced back pain. Mean tumor size was 8.4 ± 2.0 cm (range, 3.9 to 10.6 cm) and part of the tumor mass was detected in 2 patients in the sagittal view of lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The clinical information regarding to SNDTs is scarce. The authors consider that above mentioned characteristic findings may facilitate the suspicion of pelvic pathology and a search for SNDT by MRI or computed tomography should be considered in patients presenting with sciatica without evidence of spinal diseases.

Core tip: The author retrospectively studied the clinical outcomes and characteristic findings of consecutive cases of sciatic notch dumbbell tumors (SNDTs) and found that buttock mass, severe buttock pain at rest and lack of back pain may facilitate the suspicion of pelvic pathology and a search for SNDT by magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography should be considered in patients presenting with sciatica without evidence of spinal diseases.

- Citation: Matsumoto Y, Matsunobu T, Harimaya K, Kawaguchi K, Hayashida M, Okada S, Doi T, Iwamoto Y. Bone and soft tissue tumors presenting as sciatic notch dumbbell masses: A critical differential diagnosis of sciatica. World J Clin Oncol 2016; 7(5): 414-419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v7/i5/414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v7.i5.414

Sciatica is a very common disorder. Accurate diagnosis of sciatica is problematic, since it may be caused by various pathologies, including lumbar disc herniation (LDH), spinal degeneration, inflammatory diseases, trauma, metabolic or circulatory events, and tumors[1].

In particular, intra- and extra-pelvic sciatic notch dumbbell-shaped tumors [sciatic notch dumbbell tumors (SNDTs)] may cause classic sciatica by invading the sacrum, sacral plexus, and sciatic nerve. The lifetime incidence of LDH was considered to be 2%-3% and that of spinal tumor was 1 per 100000. Meanwhile, the occurrence of SNDTs is considered to be rare and there were no reports of case series with large number and the accurate incidence rate of SNDT remains unknown[2-4], and most spine and orthopedic surgeons therefore have little or no experience with sciatica caused by undiagnosed SNDTs.

Retroperitoneal bone and soft tissue sarcomas may present as SNDTs. These have a poor prognosis because of high rates of local recurrence, mortality, and surgical morbidity[5]. Early recognition of malignant SNDTs should increase the chance of survival, and thus it is essential to promptly and accurately diagnose sciatica caused by such tumors. However, very little clinical information regarding SNDTs has been published thus far[6].

In this study, we studied retrospectively the clinical outcome of 8 patients suffered from sciatica due to SNDTs. We also evaluated the characteristic features of these tumors on physical examination and imaging analysis, with the aim of improving the differential diagnosis of sciatica.

This study was approved by institutional review board in our hospital. The clinical findings and surgical records of consecutive eight cases of SNDTs were retrospectively reviewed. The following information was retrieved from medical records: Demographic details, disease history, imaging manifestations, tumor pathology, details of surgical treatment, and postoperative survival and tumor recurrence. SNDT specimens were used for histopathological analysis and final diagnosis. To establish the tissue diagnosis, either computed tomography (CT)-guided needle biopsy or open biopsy were carried out. All patients underwent a clinical examination in which the chief complaint and mode of illness onset were noted in a standardized manner. Physical examination was performed at the first medical visit. Patient delay was defined as the duration between the onset of each patient’s initial symptoms and their first physician consultation, while physician delay was defined as the period from the patient’s first medical visit for their symptoms until the date of accurate diagnosis.

X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and CT images of the pelvis were taken in all cases. Lumbar MRI was performed in 7 patients. Two orthopedic surgeons with more than 5 years’ experience independently investigated all imaging results: For X-rays, bone destruction and matrix mineralization; for MRIs, tumor size, tumor boundaries, and relation between the sciatic nerve and mass on lumbar MRI sagittal imaging; and for CT, osteolytic bone destruction, tumor calcification, and enlargement of the sciatic foramen.

There were 8 cases of SNDTs (5 males and 3 females). Patients’ ages at their first medical visits ranged from 12 to 81 years, with a mean age of 35.6 ± 21.2 years (mean ± SD). With regard to the McCormick scale[7], one case was grade I, grade II in 3, grade III in 2, and grade IV in 2. Histologically, 2 SNDTs were undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas, and there was one case each of osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, neurinoma, carcinosarcoma, and solitary fibrous tumor. The patient delay averaged 11.8 mo (2 to 26 mo), while the physician delay averaged 2.6 mo (1 to 7 mo). Table 1 presents a summary of the patients’ clinical demographics.

| Case | Age/sex | McCormick scale | Histology | Patient delay (mo) | Physician delay (mo) |

| 1 | 41/F | II | Solitary fibrous tumor | 26 | 7 |

| 2 | 12/F | I | UPS | 12 | 4 |

| 3 | 27/F | III | Neurinoma | 20 | 3 |

| 4 | 36/F | II | Carcinosarcoma | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | 81/M | IV | Osteosarcoma | 5 | 2 |

| 6 | 15/F | IV | UPS | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 35/F | II | Ewing's sarcoma | 15 | 2 |

| 8 | 38/M | III | MPNST | 12 | 1 |

All 8 cases presented with sciatica. A palpable mass in one buttock was detected in 3 of the 8 cases. Of the 8 cases, 7 reported severe buttock tenderness, 4 reported muscle weakness, 7 reported pain at rest, and 6 reported a positive straight leg raise test (SLRT) (Table 2). Six cases experienced unilateral sensory disturbances of the lower limb. The dermatomal distribution of symptoms was as follows: L5 in 2 cases, L5 to S1 in 2 cases, S1 in one case, and S2 in one case. A positive SLRT was noted in 6 of the 8 cases. Remarkably, no patients experienced back pain. Taken together, the clinical features suggestive of SNDTs were as follows: A chief complaint of pain at rest, lack of back pain, a unilateral buttock mass, and severe buttock tenderness.

| SNDT (n = 8) | |

| Sciatica | 8 |

| Pain at rest | 7 |

| Back pain | 0 |

| Palpable mass in the buttock | 3 |

| Buttock tenderness | 7 |

| Motor weakness | 4 |

| Sensory loss testing | 6 |

| Positive SLRT | 6 |

On initial plain radiographs, osteolytic bone destruction was detectable in 2 of the 8 cases, while matrix mineralization was observed in one case. In each of the 8 cases, MRI of the pelvis showed a large intrapelvic and extrapelvic tumor adjacent to the sciatic notch. Maximal diameters of the mass ranged from 3.9 to 10.6 cm (mean 8.4 ± 2.0 cm). Tumor borders were clearly defined in 3 cases and poorly defined from the adjacent organ in 5 patients. The sciatic nerves were clearly connected to the tumors in 3 cases. Lumbar MRI was performed in 7 patients; importantly, in 2 of these, part of the tumor mass was detected in the sagittal view but not in axial views. On CT, destructive invasion to the bone by the tumor progression was found in 5 cases. Ectopic calcification was observed in one case and enlargement of the sciatic foramen was found in 4 cases. Imaging features of SNDTs are summarized in Table 3.

| Modalities | Descriptions | Value |

| X-ray | Bone destruction | 2 |

| Matrix mineralization | 1 | |

| MRI | Tumor size (cm) | 8.4 ± 2.0 (range, 3.9 to 10.6) |

| Indistinguishable tumor boundary | 5 | |

| Connection of the sciatic nerve | 3 | |

| Mass on lumbar MRI sagittal image | 2 | |

| CT | Osteolytic bone destruction | 5 |

| Tumor calcification | 1 | |

| Enlargement of sciatic foramen | 4 |

Two of the 8 cases were managed with surgery, one using a wide surgical margin and the other via intralesional resection. Chemotherapy was administered to the 5 patients who did not undergo surgical tumor resection. Combination of adriamycin, ifosfamide, cisplatin, and etoposide were used for chemotherapy. Chemotherapy resulted in a complete response in one case, a partial response in 2 cases, stable disease in one case, and progressive disease in one case. Five patients received radiotherapy, 3 patients underwent conventional radiotherapy, and 2 patients were treated with carbon-ion curative radiotherapy. Local recurrence occurred in 2 cases and distant metastases to the lung were observed in one case. At final follow-up, one of the 8 patients had died of disease, one was continuously disease-free, one showed no evidence of disease, and 5 were alive with disease.

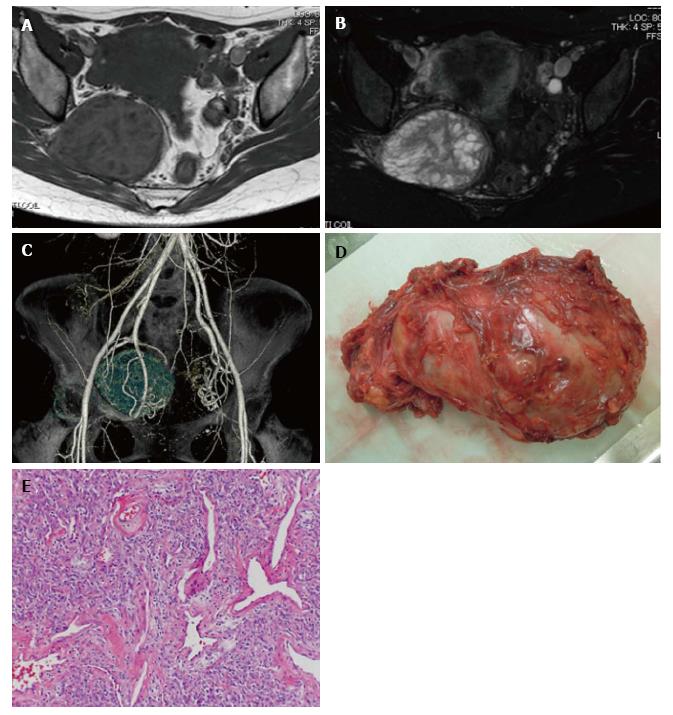

Case 1: An SNDT in a 41-year-old woman. She suffered from neurogenic claudication and sciatica for 9 mo. Examination showed moderate sensory loss in the right S1 dermatome and a nerve stretch test was positive. Lumbar MRI revealed no pathological findings; however, an intrapelvic dumbbell-shaped mass compressed lumbosacral plexus (Figure 1A and B). The maximal diameter of the mass was 7.7 cm, and the lesion showed mixed signal intensity both on T1- and T2-weighted images. 3D-CT angiography clearly demonstrated the relationship between the tumor and major vessels (Figure 1C). A diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor was made by CT-guided biopsy. The tumor was resected by a one-stage combined transabdominal and transgluteal (extrapelvic) approach (Figure 1D). A postoperative surgical specimen showed cellular proliferation of mildly atypical spindle or oval cells arranged in short fascicles that were associated with dilated sclerotic blood vessels displaying a hemangiopericytoma-like appearance (Figure 1E). The surgical margin was negative and the postoperative course was uneventful. The patient noted a significant improvement in pain. There was no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 25 mo after surgery.

Common symptoms of unilateral sciatica include pain radiating down the lower extremity, pain with motion of the hip joint, and pain in the buttock, groin, and low back. LDH is by far the most common and well-known cause of sciatica[8]. Other frequent causes include hip diseases[9], degenerative lumbar spinal disease, spinal infection, spinal and spine tumors[10], and vascular diseases[11]. Local compression of sciatic nerve by tumors and/or trauma may cause sciatica. Importantly, several reports have demonstrated that benign, malignant, and metastatic bone and soft tissue tumors in the pelvis also cause symptoms that are typical and suggestive of sciatica[12]. In particular, pelvic tumors arising adjacent to the sciatic notch have the ability to form huge dumbbell-shaped tumors[5], and compress the lumbosacral plexus, thus causing sciatica.

However, SNDTs are quite rare and there are few previous studies on these tumors. Thomas et al[13] presented 35 cases of neurogenic tumors around the sciatic nerve, 11 of which occurred at the sciatic notch. There have been few reports of SNDTs producing sciatica; these include lipoma[14] and a range of cancers[15]. Due to this rarity, SNDTs are rarely considered in the potential diagnosis of sciatica.

Physical examinations may be insufficient to distinguish SNDTs from other cause of sciatica. From the finding in this study, the authors suggest that the diagnosis of SNDT should be considered in sciatica with the following characteristics: (1) a palpable mass in one or both buttocks; (2) severe buttock tenderness; and (3) chronic pain at rest. Importantly, lack of back pain is another characteristic feature of sciatica caused by SNDTs and this should alert the clinician to consider for alternative diagnosis for sciatica. Overall, the combination of the aforementioned features may warrant the consideration of sciatic nerve compression by an SNDT, a diagnosis that may be clarified preoperatively by MRI or CT of the pelvis.

This case series demonstrated the detailed imaging features of SNDTs, and we found that in certain cases SNDTs could be identified by careful inspection of pelvic X-ray or lumbar MR images. Specifically, 2 patients showed abnormal X-ray findings and 2 demonstrated tumor masses on sagittal sections of lumbar MR images. These findings may be helpful for physicians who suspect the existence of SNDTs in patients with sciatica. SNDTs often form extraordinarily large, asymptomatic soft-tissue masses before the lesions become evident on clinical examination, even in cases of benign neurogenic tumors.

The presence of inadequate operative margins has been proven to be an independent and adverse prognostic factor in local recurrence of sarcoma of the pelvis[16]. Tumor location is a critical factor for tumor resectability. In cases of SNDTs, en bloc resection of SNDTs is not feasible because of the complex anatomic features of the surrounding organs, including the pelvic bone, lumbosacral nerve plexus, and large blood vessels. A recent report described a safe resection of certain cases of SNDTs by combination of one-stage transabdominal and transgluteal approach[5]. Accordingly, we applied this method in one case and achieved complete tumor resection with no impaired neural function. Thus, we believe that SNDTs can be resected safely and completely if the tumor displaces rather than directly involves the lumbosacral plexus (including the sciatic nerve).

In conclusion, early recognition and treatment is important in bone and soft tissue tumors. Thus in patients presenting with sciatica without evidence of spinal diseases such as LDH, prompt and accurate diagnostic strategies should include the suspicion of pelvic pathology and a search for SNDT by MRI or CT.

Sciatica, defined as pain radiating from the back into the buttocks and lower extremities, is a very common disorder. The differential diagnosis of sciatica is difficult, since it may be caused by various pathologies including sciatic notch dumbbell tumors (SNDTs).

There is little clinical information relating to SNDTs.

This study clearly describes clinical outcomes and characteristic features of SNDTs and this may improve the differential diagnosis of sciatica.

Practical clinical tips for differential diagnosis of sciatica.

SNDTs: Sciatic notch dumbbell tumors.

This is a very good article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Oncology

Country of Origin: Japan

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Malik H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Planner AC, Donaghy M, Moore NR. Causes of lumbosacral plexopathy. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:987-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Harrison MJ, Leis HT, Johnson BA, MacDonald WD, Goldman CD. Hemangiopericytoma of the sciatic notch presenting as sciatica in a young healthy man: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:1208-1211; discussion 1211-1212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McCabe DJ, McCarthy GP, Condon F, Connolly S, Brennan P, Brett FM, Hurson B, Sheahan K, Redmond J. Atypical ganglion cell tumor of the sciatic nerve. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1179-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Benyahya E, Etaouil N, Janani S, Bennis R, Tarfeh M, Louhalia S, Mkinsi O. Sciatica as the first manifestation of a leiomyosarcoma of the buttock. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997;64:135-137. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Spinner RJ, Endo T, Amrami KK, Dozois EJ, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Sim FH. Resection of benign sciatic notch dumbbell-shaped tumors. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:873-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cohen BA, Lanzieri CF, Mendelson DS, Sacher M, Hermann G, Train JS, Rabinowitz JG. CT evaluation of the greater sciatic foramen in patients with sciatica. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986;7:337-342. [PubMed] |

| 7. | McCormick PC, Torres R, Post KD, Stein BM. Intramedullary ependymoma of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:523-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Khodairy AW, Bovay P, Gobelet C. Sciatica in the female patient: anatomical considerations, aetiology and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sherman PM, Matchette MW, Sanders TG, Parsons TW. Acetabular paralabral cyst: an uncommon cause of sciatica. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:90-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Möller H, Sundin A, Hedlund R. Symptoms, signs, and functional disability in adult spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:683-689; discussion 690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Demaerel P, Petré C, Wilms G, Plets C. Sciatica caused by a dilated epidural vein: MR findings. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:113-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thompson RC, Berg TL. Primary bone tumors of the pelvis presenting as spinal disease. Orthopedics. 1996;19:1011-1016. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Thomas JE, Cascino TL, Earle JD. Differential diagnosis between radiation and tumor plexopathy of the pelvis. Neurology. 1985;35:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sato M, Miyaki Y, Inamori K, Tochikubo J, Shido Y, Shiiya N, Wada H. Asynchronous abdomino-parasacral resection of a giant pelvic lipoma protruding to the left buttock. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:975-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Taylor BV, Kimmel DW, Krecke KN, Cascino TL. Magnetic resonance imaging in cancer-related lumbosacral plexopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:823-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kawai A, Healey JH, Boland PJ, Lin PP, Huvos AG, Meyers PA. Prognostic factors for patients with sarcomas of the pelvic bones. Cancer. 1998;82:851-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |