INTRODUCTION

Cancer-related incidence and mortality increase progressively with age. It is estimated that by year 2030, 20% of the Europe population will be ≥ 65 years of age[1] and despite a decrease in overall cancer death rates, the expansion of the elderly and their inherent cancer propensity are expected to ultimately increase cancer prevalence[2]. About 60% of all tumors arise in patients older than 65 years and 70% of all deaths due to cancer occur in this elderly patient population[3-5].

Tumors of the head and neck (HNC) represent the sixth most common malignancy and account for 6% of all cancer cases. Although the majority of HNC occur between the fifth and sixth decade of life, their onset in patients older than 60 years is not rare[3], since up to 24% of HNC cases are diagnosed in patients older than 70 years[4,5]. In European case series, patients aged between 70 and 75 years represent a proportion of up to 6%-32% of all patients with HNC[3].

The aforementioned evidence underscore the necessity to focus clinical and research efforts on elderly patient population, which is often neglected in current treatment guidelines. The aim of this Review is to draw attention to this frail and under-represented, yet so important group of patients that require a multidisciplinary therapeutic approach.

METHODOLOGY

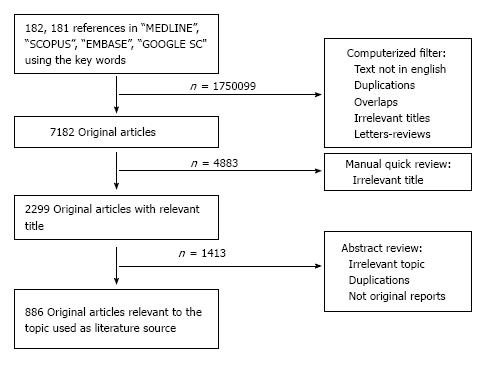

For the purposes of this Review, a comprehensive search in the literature was performed using the databases “MEDLINE”, “SCOPUS”, “EMBASE” and “GOOGLE SCHOLAR” using the key words “Head and neck cancer”, “Elderly” and either “Surgery”, “Chemotherapy”, “Targeted treatment” or “Irradiation/radiotherapy” from January 1973 to December 2012. Intial search with the two terms “Head and neck camcer” and “elderly” yielded 182191 references in the whole literature. After computerized filtering for exclusion of papers not written in English or French, duplications, overlaps, reviews or letters to the editor and irrelevant manuscript titles, the research yielded 7182 original papers. Manual quick review of these publications excluded another 4883 references irrelevant to the topic, ending up to 2299 original articles that were abstract-reviewed. This final process yielded 886 articles that were used as source for the present work (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Graphic representation of the research methodology.

DEFINING THE ELDERLY PATIENT WITH HNC

As a general rule, elderly patients are excluded from randomized clinical trials resulting in paucity of evidence-based data regarding efficacy and safety of available treatment modalities. In the literature, few studies have focused on therapeutic strategies in patients aged ≥ 75 years[6-10]. Finally socioeconomic issues such as access to medical centers and availability of caregivers may influence therapeutic strategy, as well as clinical outcomes.

Several studies indicate that older patients with HNC are less likely to receive curative treatment as compared to the younger age population[6-9]. In particular, a strikingly lower prevalence of radical treatments, including surgery and combined modalities such as surgery plus irradiation or chemotherapy plus irradiation, was evident among elderly patients as compared to their younger counterparts. The same was true for overall survival too, with an incremental rate at 5 years of 17%-31% vs 30%-44%, in the same patient cohorts[7-10]. These results were challenged, however, by other studies showing that radical surgical or radiotherapy treatment can be performed safely in elderly patients without an increase in overall complication rates, as long as the patients do not have severe comorbidities[6-8], creating thus an ongoing debate.

The definition of the elderly patient with cancer remains controversial and the thresholds used often tend to differ among various malignancies. The “traditional” age limit of 65 years used by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) has been challenged in the recent years by the increasing life expectancy, as well as the improvements in global cancer care and survival rates. Moreover, a sub-categorization of “younger old” (65-70 years), and “older old” (more than 80 years) has been introduced to allow allocation of elderly patients with cancer to homogenous patient groups.

SPECIAL FEATURES OF HNC IN THE ELDERLY

Risk factors and biology

HNC is a predominantly male disease with the usual male to female ratio ranging from 8:1 to 15:1[7]. Nevertheless, Ang et al[7] reported an increased incidence of females among the elderly patient population compared to the younger one (15.8% vs 4.4%, P < 0.001). The major risk factors for HNC include tobacco use (85%) and alcohol consumption both reported in up to 70% of HNC patients[7-9]. However, elderly patients have been reported to have a significantly lower prevalence of alcohol and tobacco exposure, as compared to their younger counterparts[3]. This finding follows the rational that malignant tumors occur earlier under the influence of risk factors, but are also likely to occur without them as time passes by[6]. As a proof of this concept, in a French cohort of 270 consecutive patients aged ≥ 80 years with cancer of the oral cavity, tobacco or alcohol intoxication was the main risk factor among male individuals[10]. HPV-positive tumors are also more likely to occur in younger patients, although it has been suggested that they can contribute in HNC carcinogenesis in older patients as well[7].

HNC in the elderly seem to share a specific epidemiological profile thus implying that the molecular profile of these tumors could also be specific. According to the results from studies assessing carcinogenesis in the elderly patient population, a series of spontaneous mutations rather than an increased exposure to carcinogenic substances is responsible for tumour cell transformation[8]. Because of those mutations, as well as the ageing process, hypomethylation of the DNA was recognized as the underlying mechanism leading to malignant transformation[9,10]. Moreover, recently published Genome-Wide Association studies implicate a number of important cellular processes in NHC neoplastic transformation, including deregulation of tumour-suppressor-genes, inactivating mutations in the molecular pathway of squamous differentiation (Notch/TP63 pathway), loss-of-function mutations in proliferative cell-signaling and impairment of epigenetic integrity[11]. These studies discovered mutations in genes involved in the differentiation program of squamous epithelium and Notch/p63 axis (such as NOTCH1, TP63 and FBXW7), and validated findings derived from previous genetic studies (such as mutations in TP53, CDKN2A, PIK3CA, CCND1 and HRAS) as driver genetic events in SCCHN neoplastic transformation.

Tumor distribution and histology

HNC is a heterogeneous disease entity comprising cancers originating from the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, oral cavity, pharynx and larynx[12]. In western countries, the three latter locations are the ones most usually affected in the elderly patients. In a recent study evaluating 316 patients with HNC of 80 years of age or more, Italiano et al[13] reported that 46% of the tumors were located in the oral cavity, 23% in the laryngeal, 19% in oropharyngeal, and 4% in hypopharyngeal sites whereas in 7% of the patients, another site was also involved. Finally, Jun et al[14] reported a series of 159 patients aged > 80 years in whom 53% of tumours were located in the oral cavity, 10.9% in the larynx, and only 5.8% in the pharyngo-laryngeal area.

The most common histological type of HNC is squamous cell carcinoma (95%), followed by less common types including salivary gland tumors, lymphomas and sarcomas[15]. Nevertheless, a rare histological type of well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, called verrucous type of SCCHN, is more prevalent in elderly patients[16]. In the following paragraphs, the term HNC, as well as the presented data will refer to squamous-cell carcinoma, which is the pre-dominant histological subtype.

Stage and clinical features

In general, nearly two-thirds of HNC patients present with locally advanced disease, whereas metastatic disease at diagnosis is documented in about 10% of patients[3]. Elderly patients have been reported to present more often with locally advanced disease (T3 or T4, in TNM staging) but with a lower incidence of regional lymph node metastasis at diagnosis[3,8]. Cancer stage at diagnosis was equally distributed between the older patients and the younger ones-31.1% vs 29.8% for those with stages I and II, 37.9% vs 37% for those with stage III, and 31% vs 33.2% for those with stage IV, respectively[8]. Metastatic disease usually occurs in distal lymph-nodes and, in late stages of the disease, in lung parenchyma or the liver via hematogenous spread.

In elderly patients the length of their symptoms history is of potential clinical importance, since a median duration of complaints dating up to 15.5 wk until the patients sought medical advice has been reported[7]. Older patients tend to perceive several-otherwise alerting-symptoms as normal in the ageing process, or to attribute them to common colds or upper aero-digestive tract infections. Additional medical and social problems of the elderly generation such as social isolation due to the loss of partner or friends, the distance to children or other relatives, limited mobility, hearing loss, visual loss, other physical handicaps, or already existing diseases occupy more space in the awareness of the patients than cancerous diseases which they are not used to discuss openly[6]. Thus an eventual newly developed malignant disease is likely to be neglected, as long as the symptoms do not influence daily routine[6,17]. Importantly, elderly patients should be educated to report their symptoms to the family physician or a specialist, who should have a high level of suspicion for diagnosis of this particular disease and should alert the patient in case of heralding symptoms and signs.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH OF HNC IN THE ELDERLY

General principles

Because of their frail nature, treatment of geriatric patients with HNC sometimes necessitates compromises and the use of suboptimal regimens which are better tolerated than standard treatment. Surgery was reported to be less often used for older patients: 13.9% vs 27.4% for the primary site and 15.4% vs 35.6% for neck lesions[18]. Combined modalities including surgery and irradiation or chemoradiotherapy were also less frequently administered in the elderly patient population than in the younger patients: 22.3% vs 9.7% and 14.1% vs 0.2%, respectively[19]. Systemic chemotherapy as exclusive treatment was less frequently used for elderly: 5.5% vs 17.6% and, even in these cases, it was mainly used as palliative treatment.

For a long time undertreatment was attributed to assumed poor tolerance and compliance to treatment in older patients. The available data currently suggest that curative therapy should be offered in elderly HNC patients, not only because of the reversible nature of therapy-associated toxicities but also because of the relatively good prognosis[6]. Chronological age by itself is an unreliable parameter for decision making. The treatment of choice should be based on a medical assessment and the preferences of the patient, not on chronological age alone[18].

Surgery

Feasibility: Surgery should be offered as the preferred treatment when the primary tumor can be removed with clear margins without causing major functional compromise; Such an aggressive approach with a curative intent can also be considered for the elderly HNC patients[19]. The choice of radical local therapy must be based on a number of aspects, including the potential functional outcome of treatment, the comprehensive geriatric assessment, the life expectancy and, importantly, the patient’s wishes.

As has been previously suggested[3,19,20], chronological age alone should not be a contraindication to aggressive surgical approach, which should be attempted whenever risk-assessment ration is favorable. In a large retrospective series of 810 patients > 65 years who had undergone major head and neck resections, Morgan et al[21] reported an acceptable overall mortality rate of 3.5%. Aggressive surgical approach should include attempting a radical surgical excision that removes thoroughly the tumor without compromising functional outcomes.

Preoperative risk assessment: According to the series from Serletti et al[22] prolonged surgical time longer than 10 h serves as a predictive factor for the development of postoperative surgical complications. In another study[22] assessing 121 patients treated for HNC, after stratification according to their age, a number of surgery-related complications, occurred in 53% of the elderly patient group. Notably, tumor-specific 5-year survival rates were absolutely comparable 85.2% for the younger patients and 84.5% for the aged (> 65 years)[22]. In a third large study[23] among 242 patients aged 70 years or more who underwent surgery with curative potential for HNC, co-morbidities were present in 87.6% of the patients and 56.6% had some type of postoperative complication.

Radiotherapy

Dose intensity: As a general rule, the primary tumor and gross lymphadenopathy require a total dose of 70 Gy at a dose fractionation of 2 Gy/d, while radiation to suspected unresected microscopic disease in nodal levels requires a total of 50 Gy or more at 2 Gy/d[6]. An important issue is whether the reduction of the clinical target volume (CTV)-in an effort to minimize adverse events, is acceptable in this frail group of patients. In this context, Ortholan et al[23] reported that the omission of regional lymph-node irradiation for T1-T2 N0 oral cavity cancer in patients more than 80 years of age is associated with a high risk of node recurrence.

Toxicity and efficacy: Several studies have shown that RT is effective and well tolerated in the elderly patient population and advanced age alone should not be considered a contraindicator for radiation therapy[24-28]. Nevertheless, it has been reported more than a decade ago that elderly patients with HNC recruited in clinical trials had a better performance status compared to those who were not included in clinical trials; therefore, the results from clinical trials might be biased and not generalizable to the general aged HNC population[29]. Besides those limitations a meta-analysis of HNC patients enrolled in the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trials using standard treatment approaches demonstrated that survival and late toxicity were similar for each age group[20]. However, a subsequent meta-analysis found that the benefit of intensified radiotherapy (RT) regimens was diminished in the elderly patients enrolled in chemoradiotherapy or accelerated RT[30] trials, probably owing to competing risks from co-morbidities. In another study[31], among 1487 patients who received definitive radiotherapy, no differences were found between the elderly and younger patients in terms of treatment interruption, completion and treatment-related death. Within the subset of 760 patients who received intensified treatment (concurrent chemoradiotherapy or hyperfractionated accelerated RT), no difference was seen between the elderly and younger patients with respect to the outcome. Of note, after a median follow-up of 2.5 years, the two-year cause-specific survival rate after definitive RT for the elderly and for the younger patients was 72% and 86%, respectively[31]. Despite their retrospective nature, these results suggest that the outcome in elderly patients is comparable to that of younger patients[32].

Palliative radiotherapy: It has been argued that the use of palliative RT in HNC elderly patients is potentially hazardous due to the presumed significant toxicity resulting from the dose used in order to achieve a clinical benefit[33]. However, regarding the tolerance of radiotherapy, in a series of 1589 patients included in the EORTC trials between 1980 and 1995 with 20% of patients aged > 65 years and 2% aged > 75 years, the aforementioned meta-analysis[20] concluded that adverse mucosal rates increased with age of the patients, with 8% of severe toxicity in patients aged less than 50 years and 31% in those more than 70 years of age. Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant difference in survival or severe mucosal reactions and in weight loss rates more than 10% between the two age groups. However, older patients experienced more frequently severe functional toxicity, as compared to their younger counterparts.

Fractionation and transportation issues

An aspect of particular clinical importance is the number of daily transportations required for HNC radiotherapy, which in standard fractionation, necessitates approximately 35 daily transportations for more than 7 wk, a process that has been associated with increased fatigue in the elderly patients over time[34]. Inevitably, treatment interruption due to fatigue or to socioeconomical reasons is frequent in elderly patients[6,35]. Many hypofractionated palliative schedules for HN cancers have been proposed including 20 Gy in five fractions[35], 30 Gy in five fractions[36], 14 Gy in four fractions[37], and 50 Gy in 16 fractions[38]. Nonetheless, increased late toxicity rates were still reported for those patients treated using a hypofractionated schedule[39]. In every case, practical issues regarding transportation and number of hospital visits should be always taken into account in the multidisciplinary care of elderly patients with HNC because they can profoundly affect the quality of life of the patient.

Chemotherapy

Feasibility and tolerability: Chemotherapy in HNC can be administered with different potentials: (1) in combination with locoregional therapy (surgery or radiotherapy) in patients with locally advanced disease; (2) as neoadjuvant/induction when it is delivered before surgery or radical radiotherapy; (3) as adjuvant when it is delivered following radiotherapy or surgery; and (4) as the only treatment in recurrent or metastatic disease. The standard chemotherapy regimen for advanced HNC is a combination of cisplatin and infusional 5 fluorouracil (5FU) and usually achieves response rates of up to 40%-50% in the recurrent or metastatic setting, whereas in the induction setting attempted for organ preservation, this combination may yield response rates of up to 70%-80%[40]. The incorporation of chemotherapy to locoregional treatment (surgery or irradiation) for patients with locally advanced HNC has been consistently reported to improve survival[41]. The incorporation of cisplatin in post-operative irradiation has been reported to be beneficial in cases of either positive surgical margins or extracapsular node involvement[42]. A synchronous study suggested for the first time that the size of benefit with concurrent chemoradiotherapy is age dependent, with the largest benefit in patients younger than 60 years of age and at the expense of increased acute early and late toxicity[42]. Docetaxel has been the only chemotherapeutic regimen that offered an absolute survival benefit when added to the cisplatin-fluorouracil combination, including the elderly[43]. In a confirmatory study with 10% of the patients aged between 65 and 71 years old, induction chemotherapy with the addition of docetaxel to the standard regimen of cisplatin and fluorouracil significantly improved progression free and overall survival in patients with initially inoperable-advanced HNC[44].

Elderly patients have been considered subjects at high risk for toxicity from cytotoxic agents[3,6,45], since age has been associated with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and with increased susceptibility of normal tissues to toxic complications or reduced capacity of healthy tissues to recuperate. Besides the “classical” toxicities observed with cytotocic agents (anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, fatigue, anorexia and gastrointestinal abnormalities), chemotherapy may affect cognition, continence, vision, balance and even mood[6]. In elderly patients with other tumor types, no major age-related differences in drug clearance were demonstrated for docetaxel and paclitaxel[46,47]. The hematopoietic reserve is also reduced in the elderly, which renders them more susceptible to chemotherapy-induced myelotoxicity[48].

“To chemo or not to chemo?” The ongoing debate: A number of retrospective studies in various solid tumors have reported that toxicity in general is not increased in the elderly[49-51], although these results have been challenged by other studies[52-54]. In elderly patients with advanced HNC in particular, combined data from two phase III randomized trials[43], conducted by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group attempted to clarify the obscure landscape: The trial E1393 compared cisplatin plus paclitaxel at two dose levels and the trial E1395 compared cisplatin plus fluorouracil to cisplatin plus paclitaxel; Both trials evaluated clinical outcomes and toxicity in patients 70 years or older as compared to their younger counterparts[55]. As commented by the authors, “fit” elderly patients sustained increased toxicities with platinum-based combinations, but had comparable survival outcomes to younger patients. It should be noted, however, that the number of elderly patients was strikingly low (13% were 70 years or older and 30% 65 years or older), highlighting thus the problem of participation of elderly patients with HNC in clinical trials, even when the crucial question of the clinical trial is the age effect.

Targeted and combined therapy

Cetuximab is a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody against the ligand-binding domain of EGFR that has been proven to possess synergistic cytotoxic effect with radiation against HNC[55-58]. The largest to date randomized controlled trial involved 424 patients and demonstrated that in locally advanced disease, concurrent administration of cetuximab, with radical external beam radiotherapy resulted in an 11% reduction in progression and a 10% improvement in overall survival[55]. There are no clinical studies assessing the efficacy or tolerability of cetuximab particularly in the elderly patient population: In the aforementioned study only 11% of patients were 70 years of age or older at study entry; however, the demonstrated activity of cetuximab with concurrent radiotherapy, along with the reported good tolerance of the combination and low toxicity, suggest that it could represent a valid alternative to the combination of platinum compounds with radiotherapy in elderly patients unfit for cisplatinum administration due to nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity or sensory neuropathy. Other targeted agents are currently under early clinical evaluation in HNC including angiogenesis inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immunotherapy.

Clinical endpoints and their assessment in elderly patients with HNC

Survival is not easy to assess in a population that has, by definition, a rather short life expectancy even when a malignant disease has not been diagnosed. An 80-year-old person, for example, had a life expectancy of a further 8 years and a 70-year-old person had a life expectancy of a further 15 years in the ninth decade of the twentieth century in western countries. Patients older than 80 years have a 1.68-fold increased risk of death, even when adjusted for variables such as the severity of co-morbidities, clinical stage and functional status. Thus, as expected overall survival was significantly lower in elderly patients, with an actuarial rate at 5 years of 17%-31% vs 30%-44% in younger patients in the same case series of HNC patients[56-58]. However, these differences tend to deteriorate or even disappear, in the case series where cancer-specific survival is analyzed and/or the groups of patients are homogeneous in terms of radicality of treatment. When considering cancer-specific overall survival, the difference between the two groups was at borderline statistical level, being at 5 years 55% vs 59%, respectively[59,60]. Cancer-specific overall survival was similar between the two groups for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer, whereas elderly patients with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer had a significantly worse 5-year cancer-specific overall survival compared to their younger counterparts (71% vs 78%, P = 0.02 and 30% vs 42%, P < 0.01)[61]. In the case-control study by the surveillance, epidemiology and result data base of Baltimore, on 2508 cases of HNC in patients older than 50 years, cancer-specific survival of patients older than 70 years has been shown to be comparable to that of patients of 50-69 years, with the exception of stage I and IV glottic carcinoma and stage III tonsil carcinoma, where cancer-specific prognosis has been demonstrated to be worse and better in elderly patients, respectively[3].

CONCLUSION

Elderly patients can cope, tolerate and adapt remarkably well and several studies have shown that the quality of life of elderly patients undergoing curative treatment for cancer of the head and neck is comparable to that of the younger population[61-63]. Despite the aforementioned data, elderly patients with cancer of the head and neck are less likely to receive standard treatment including radical surgery or postoperative chemo-radiotherapy, which probably contributes to poor outcomes reported in those patient populations[6]. There is thus an absolute necessity to improve the framework of cancer care for this frail subgroup of patients and provide them with adequate physical and emotional support that they need, especially at this period of their life.

Today, it is well recognized that elderly patients with HNC tend to receive suboptimal treatment, mainly due to fears of poor adherence and/or tolerance, excessive toxicity or lack of support from their environment. Nevertheless, it becomes increasingly apparent that medical intervention in the elderly should be guided by the benefit/risk ratio, as estimated by the co-evaluation of the expected treatment outcome, the life expectancy of the patient, the possible therapy-related toxicities and the patient tolerability. There is now international consensus, that elderly patients affected by HNC should be treated on the basis of a curative intent, as long as comprehensive preoperative evaluation of existing co-morbidities is performed and optimal management of concomitant morbidities is completed. Age itself should never guide therapeutic decision, but a holistic, multidisciplinary approach addressing the real needs of the patient, as well as her/his wishes, should be implemented and maintained throughout the whole therapeutic process.