Published online Dec 10, 2014. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i5.792

Revised: June 22, 2014

Accepted: September 6, 2014

Published online: December 10, 2014

Processing time: 207 Days and 11 Hours

The sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was initially pioneered for staging melanoma in 1994 and it has been subsequently validated by several trials, and has become the new standard of care for patients with clinically node negative invasive breast cancer. The focussed examination of fewer lymph nodes in addition to improvements in histopathological and molecular analysis has increased the rate at which micrometastases and isolated tumour cells are identified. In this article we review the literature regarding the optimal management of the axilla when the SLNB is positive for metastatic disease based on level 1 evidence derived from randomised clinical trials.

Core tip: There has been a shift in the management of the axilla when the sentinel lymph node biopsy is positive towards less radical surgery thus reducing the incidence of arm morbidity and improving the quality of life of our patients.

- Citation: Wazir U, Manson A, Mokbel K. Towards optimal management of the axilla in the context of a positive sentinel node biopsy in early breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5(5): 792-794

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v5/i5/792.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v5.i5.792

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was pioneered for the staging of melanoma in 1994[1]. Shortly thereafter, Giuliano et al[2] demonstrated the feasibility of SLNB for breast cancer. Over the subsequent two decades, the SLNB has been validated by several trials, and has become the new standard of care for patients with clinically node negative invasive breast cancer. Since the SLNB is positive in approximately 30% of patients undergoing surgical treatment of clinically node negative breast cancer, therefore, 70% of women are now able to avoid radical surgery, in the form of complete axillary node dissection (ALND), which is known to be associated with a higher incidence of morbidity and longer hospitalisation, with impairment of quality of life[3].

The SLNB technique formally utilises a radioactive isotope tracer in addition to a blue dye. When both modalities are used, the proceduce has been reposted to be 96% accurate when performed by an experienced operator[4]. It was noted in early studies that there was not any identifiable advantage of lymphoscintigraphy mapping even for surgeons learning the techniques. Intra-operative frozen section analysis of the sentinel node has been shown to be accurate for the evaluation of metastatic disease with high sensitivity and excellent specificity[5].

Since the sixth edition of the AJCC/UICC TNM classification, the extent of metastatic disease in the sentinel node has been classified into three categories: isolated tumour cells (ITCs; < 2 microns); micrometastatic disease (MM; 2 microns-2 mm); and macrometastatic disease (> 2 mm). In addition, the sixth edition also mentions real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as a possible means of detecting cancerous cells in sentinel nodes[6].

ITCs and MM have become more common findings due to the increased use of immunohistochemistry (IHC). In the current seventh edition of the TNM staging, the trends noted in the previous edition have become the norm in most major centres[7]. Similarly, new refinements in RT-PCR, such as One-Stop Nodal Analysis, have been recently introduced for intra-operative evaluation, and have been demonstrated to be even more sensitive for detecting metastatic deposits than IHC[8].

The clinical implications of these findings was unclear, with little progress towards a consensus until very recently due to non-availability of suitable level evidence[9-11]. Although the presence of ITCs in the sentinel nodes has a prognostic significance, however, there is a consensus that it does not represent an indication for further treatment of the axilla[11]. The presence of micrometastatic disease in the sentinel node was, until recently, considered an absolute indication for a complete axillary node dissection. However, more recent evidence is highly suggestive that a more conservative approach to such micro-deposits would be more appropriate despite modest upstaging of the disease[9]. A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) confirmed the oncological safety of omitting complete ALND for MM positive SLNB (IBCSG 23-01)[12].

Until recently the presence of macrometastases in the sentinel nodes has been considered a routine indication of complete ALND, however, a recent randomised controlled trial carried out by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (Z0011) showed that in women undergoing breast conserving surgery (BCS) for clinically node negative T1/T2 invasive breast cancer, complete axillary node dissection is not required if only 1-2 sentinel nodes were found to be involved by malignancy. The five year disease-free survival and overall survival were similar in the axillary node dissection group vs no axillary node dissection group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in relation to the primary tumour characteristics and the use of adjuvant systemic therapy. All the patients received adjuvant radiotherapy following breast conserving surgery[13]. Therefore, patients who fulfil the criteria for this mature trial can avoid complete ALND, which is associated with a higher incidence of complications. The presence or absence of extra-capsular extension (ECE) was not analysed in this trial. A recent retrospective study showed that the presence of an ECE greater than 2 mm in the sentinel nodes was associated with significant tumour burden in non-sentinel nodes during ALND and therefore this feature can be added to the eligibility criteria for omitting ALND when the SNB is positive (i.e., ECE < 2 mm)[14].

Complete axillary node dissection is still indicated in women undergoing breast conserving surgery, who are found to have metastatic disease involving three or more lymph nodes and those undergoing total mastectomy with positive sentinel node biopsy involving any lymph nodes.

In a further shift towards less radical surgery to the axilla, the recent EORTC ARAMOS randomised controlled trial showed that axillary radiotherapy was as effective as complete axillary node dissection in terms of five year overall and disease-free survivals. Furthermore, radiotherapy (50Gy in 25 fractions) was associated with a lower incidence of lymphedema of the arm, in the short and long terms. The authors, however, observed non-significant trend towards impairment in the shoulder movement in women undergoing radiotherapy to the axilla in the short term. Earlier analysis of the trial data showed that the lack of knowledge of the pathological status of the non-sentinel nodes did not influence the treatment decisions in relation to adjuvant systemic therapy[14]. Moreover, oncologists are increasingly basing their systemic treatment recommendations on the use of multigene molecular signatures of the primary tumour, such as Mammaprint®, Oncotype DX®, and Endopredict®.

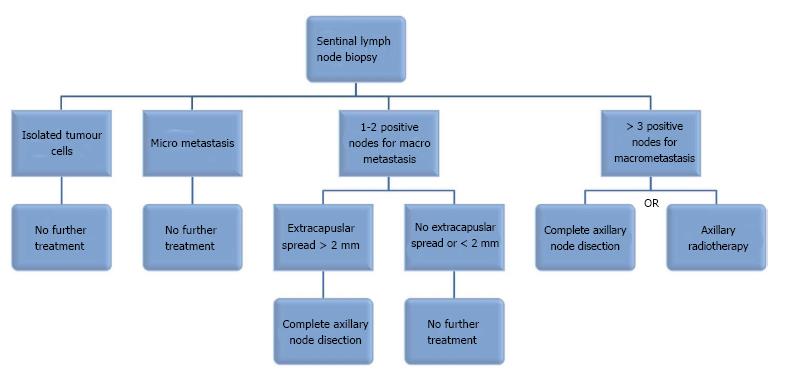

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has recently updated its guidelines to reflect the results of these trials[15]. The adoption of these guidelines worldwide will spare thousands of women radical surgery to the axilla, which is associated with a higher incidence of complications and longer hospitalisation without compromising their clinical outcome. Needless to say that the final treatment recommendations are made in the contex of multidisciplinary discussion. The findings of these trials are consistent with the biological behaviour of breast cancer and the longstanding perception that axillary surgery aims to provide staging and prognostic information to guide systemic treatment and radiotherapy recommendations rather than achieving mechanical eradication of the disease. Evidence-based medicine means that we should embrace the results of these RCTs and introduce the new ASCO recommendations into our clinical practice in order to improve the quality of life of our patients. The proposed management of a positive SLNB in patients undergoing BCS for T1-T2 breast cancer has been summarised in the algorithm shown in Figure 1.

P- Reviewer: Kitai T, Wang LS S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, Economou JS, Cagle LA, Storm FK, Foshag LJ, Cochran AJ. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127:392-399. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220:391-398; discussion 391-398. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, Luini A, Zurrida S, Galimberti V, Intra M, Veronesi P, Maisonneuve P, Gatti G. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:983-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Posther KE, McCall LM, Blumencranz PW, Burak WE, Beitsch PD, Hansen NM, Morrow M, Wilke LG, Herndon JE, Hunt KK. Sentinel node skills verification and surgeon performance: data from a multicenter clinical trial for early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:593-599; discussion 593-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Morrow M, Rademaker AW, Bethke KP, Talamonti MS, Dawes LG, Clauson J, Hansen N. Learning sentinel node biopsy: results of a prospective randomized trial of two techniques. Surgery. 1999;126:714-720; discussion 720-722. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Singletary SE, Greene FL. Revision of breast cancer staging: the 6th edition of the TNM Classification. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Greene FL. Breast tumours. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 2009; 181-193. |

| 8. | Chaudhry A, Williams S, Cook J, Jenkins M, Sohail M, Calder C, Winters ZE, Rayter Z. The real-time intra-operative evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients using One Step Nucleic Acid Amplification (OSNA) and implications for clinical decision-making. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:150-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patani N, Mokbel K. The clinical significance of sentinel lymph node micrometastasis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:393-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salhab M, Patani N, Mokbel K. Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis in human breast cancer: an update. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:e195-e206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Patani N, Mokbel K. Clinical significance of sentinel lymph node isolated tumour cells in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:325-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, Viale G, Luini A, Veronesi P, Baratella P, Chifu C, Sargenti M, Intra M. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 782] [Cited by in RCA: 889] [Article Influence: 74.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Miller CL, Specht MC, Skolny MN, Horick N, Jammallo LS, O’Toole J, Shenouda MN, Sadek BT, Smith BL, Taghian AG. Risk of lymphedema after mastectomy: potential benefit of applying ACOSOG Z0011 protocol to mastectomy patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rutgers EJ, Donker M, Straver ME, Meijnen P, Van De Velde CJH, Mansel RE, Westenberg H, Orzalesi L, Bouma WH, van der Mijle H. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer patients: Final analysis of the eortc amaros trial (10981/22023). ASCO Annual Meeting Abstracts; 2013. J Clin Oncol. 2013;LBA1001. |

| 15. | Lyman GH, Temin S, Edge SB, Newman LA, Turner RR, Weaver DL, Benson AB, Bosserman LD, Burstein HJ, Cody H. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1365-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |