Published online Dec 10, 2014. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i5.1117

Revised: September 23, 2014

Accepted: October 14, 2014

Published online: December 10, 2014

Processing time: 254 Days and 15.4 Hours

Ectopic thymic tissue can be present in the thyroid gland and a carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) may arise from such tissue. We are reported the case of a 26-year-old man with CASTLE, with cervical subcutaneous nodules relapse, who showed a good response to treatment with surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The problematic aspect of this case was the diagnosis; only on review were we able to make a final diagnosis. CASTLE is a very rare neoplasm. It is important to differentiate this cancer from others tumors such as primary or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or squamous cell thyroid carcinoma, because the therapy and prognosis are different. Diagnosis is complicated and requires careful histological analysis (CD5- and P63-positive with presence of Hassall’s corpuscles); unfortunately there is no gold standard treatment so, in this case, we administered a sandwich of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Core tip: Carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) is a very rare tumor and is very important to differentiate it from others head and neck tumors because therapy and prognosis are different. Moreover, diagnosis is often complicated. Case reports on this topic, reporting treatment modalities, are useful, because there is no standard treatment for CASTLE.

- Citation: Abeni C, Ogliosi C, Rota L, Bertocchi P, Huscher A, Savelli G, Lombardi M, Zaniboni A. Thyroid carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation: Case presentation of a young man. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5(5): 1117-1120

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v5/i5/1117.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v5.i5.1117

It is possible for ectopic thymic tissue to be present in the thyroid gland and a carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) may arise from such tissue. CASTLE is a rare type of cancer; first described by Miyauchi et al[1] in 1981, it was not until 2004 that the World Health Organisation recognised it as an independent clinico-pathological entity and classified it as a type of thyroid tumor[2]. We present the case of a young man with a diagnosis of locally advanced CASTLE.

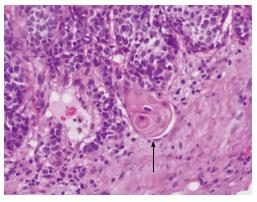

A 26-year-old Caucasian male with no family history of neoplastic diseases and no comorbidities was examined by his general practitioner after developing minimal neck oedema and throat tightness; ultrasound of the neck was requested. The first step diagnostic procedures showed normal morphology and ultrasonography of the thyroid, with the exception of a suspicious nodule (about 3 cm of diameter) which was investigated cytologically with FNA and found to be positive for neoplastic cells (even if the diagnostic material was poor). The patient consequently underwent total thyroidectomy. The histological diagnosis was a poorly differentiated carcinoma of the thyroid, pT3N1b (6/6). Immuno-histochemistry (IHC): TTF1-positive (focal), thyroglobulin-positive (focal), CD56-positive (focal), NSE- and P63-positive. No adjuvant anti-neoplastic therapy was recommended. One month later, ultrasound examination of the neck revealed pathological changes at multiple right lateral cervical lymph nodes, confirmed by head and neck magnetic resonance. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning did not show distant disease but detected neoplastic activity in bilateral cervical lymph nodes (Figure 1). Bilateral functional type lymphadenectomy of cervical lymph nodes was done, with 5/47 lymph nodes positive for metastases of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma and involvement of the right anterior margin of the sterno-mastoid muscle. About one month later, the patient came to our hospital for the first time. Physical examination showed multiple subcutaneous nodules near the surgical scar. This abnormal evolution of thyroid carcinoma prompted us to review the histological examinations. We found that the thyroid was characterised by intra-thyroid tumour growth including solid nests of epithelioid elements with high mitotic activity (14 × 10 HPF). There were also groups of squamoid cells similar to Hassall’s corpuscles. The tumour had a lobulated profile and showed marked vascular invasion.

IHC analysis revealed: (1) P63: diffuse and strong nuclear positivity; (2) CD5: multifocal cytoplasmic positivity; (3) TTF1: nuclear positivity in the remaining follicular cells (both in follicles and in the collapsed regions within the tumour); (4) Thyroglobulin: positivity in the remaining follicular cells; and (5) Synaptophysin, calcitonin, chromogranin, CD56: negative; our revised diagnosis was CASTLE.

In view of the results of the histopathological review, a second local relapse within a few months, and a Computed Tomography (CT) scan negative for distant disease, we planned a therapeutic program which included chemo-radiotherapy: 2 cycles of chemotherapy, followed by radiotherapy, followed by 3 further cycles of chemotherapy using the same regimen. The chemotherapy administered was carboplatin AUC 6 and paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 q21. Radiation was delivered by daily volumetric intensity-modulated arc therapy with cone-beam CT image-guidance. A parotid-sparing simultaneous integrated boost technique allowed the delivery of three different dose levels prescribed according to tumour burden: 66.0Gy in 33 fractions on the thyroid bed (site of macroscopic residual disease), 59.4Gy in 33 fractions on the right cervical nodes, levels II-V (site of positive extracapsular nodes) and a precautionary dose of 54.45Gy in 33 fractions on left cervical nodes, levels II-V and bilateral recurrent nodes showing excellent clinical response i.e., disappearance of subcutaneous nodules. The most significant side-effects during the radiation treatment were: cervical skin erythaema G2, desquamation in the thyroid bed, oropharyngeal mucositis G1 and sore throat; the chemotherapy was well-tolerated. At the end of the treatment the CT scan was negative and the first follow-up 3 mo later was also negative.

CASTLE is a very rare neoplasm which arises in the thyroid gland or the soft tissue of the neck. It is necessary to differentiate CASTLE from the others tumours such as primary or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or squamous cell thyroid carcinoma, because the therapy and the prognosis are different[3]. There are two theories of the histogenesis of this cancer, the first suggests that CASTLE arises from thymic nests near the thyroid gland which occur as a result of persistence of cervical thymic tissue during embryogenesis; the alternative theory proposes that it arises from remnants of the branchial pouches that differentiate along the thymic line[3]. The expression of the IHC marker CD5 by CASTLE cells provides support for the latter theory[4]. The diagnosis of this disease is complicated by its cyto-histological presentation. Microscopically it appears to be arranged in broad, smooth-bordered islands abutting a desmoplastic cellular stroma[5]. The tumour cells show squamoid characteristics, having eosinophilic cytoplasm, oval nuclei and small distinct nucleoli. Within the lymphoid stroma Hassall’s corpuscles may be seen at the periphery of the tumour; this may be an additional characteristic of this neoplasm[6]. In this case the pathologist was alerted to the possibility of CASTLE by the presence of Hassall’s corpuscles at the review of the histological findings. The IHC analysis showed a tumour that was strongly positive for pancytokeratin, CD5, P63, focal positive for CEA[4-7]; somewhat positive for chromogranin-A and synaptophysin[8] and negative for TTF-1, thyroglobulin, chromogranin and calcitonin[9] (Table 1). In this case CD5- and P63-positive IHC and the presence of Hassall’s corpuscles were the two most important elements in the diagnosis (Figure 2, 3 and 4). In the literature this neoplasm is considered an indolent, slow-growing cancer even when regional lymph node metastasis is present[7-10]. There is no gold standard treatment for this rare lesion although it appears that the first line treatment of choice is surgery with or without adjuvant radiotherapy[3-11]; we therefore suggested a treatment adapted to the needs of our young patient. We used the type of chemotherapy that we normally give to patients with cancer of the thymus. In this case we administered a sandwich of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The radiotherapy protocol was similar to that used for thymus tumours, but we reduced the dose intensity because the irradiated volumes were so big that the risk of toxicity for the patient was very high. Currently the patient is feeling well. If this patient had been given radiotherapy after the first surgery would he have relapsed? Unfortunately the literature does not provide evidence on this issue.

| ICH | CD5 | Calcitonin | P63 | Synaptophysin | TTF-1 | Thyroglobulin | Cromogranin | CD117 |

| Anaplastic carcinoma | neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos/neg | Neg | Neg | Neg/pos |

| CASTLE | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos/neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Focal pos |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Neg | Neg | / | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg/pos |

| Case report | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Focal pos | Neg | Neg | / |

A further problem is determining the best radiological technique for staging and follow-up: there are currently no guidelines. In this case we did a total body CT-scan, PET-FDG and MRI of the neck for the staging, but used only a CT-scan for the first follow-up. Although our patient is younger than other cases reported in the literature, we were not able to find epidemiological, genetic or other explanations for his disease. This makes it more difficult to plan follow-up in order to prevent or achieve early diagnosis of other cancers or non-oncological diseases which may arise as ancillary pathological consequences of this rare tumour in this young patient.

A 26-year-old Caucasian male with a history of carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE).

Neck edema and dysphagia.

Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or squamous cell thyroid carcinoma.

Within normal limits.

The first step diagnostic was an ultrasonography of the thyroid that showed of a suspicious nodule, which was investigated cytologically and found to be positive for neoplastic cells.

The thyroid was characterised by intra-thyroid tumour growth including solid nests of epithelioid elements and also groups of squamoid cells similar to Hassall’s corpuscles.

The patient was treated with surgery followed by a sandwich of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

For this case there is no gold standard treatment so we were treated the patient as a patient with a thymic cancer.

The importance of a multidisciplinary approach and the case’s sharing could improve patient management.

The manuscript is well written and reported diagnosis and treatment of a rare case of CASTLE.

P- Reviewer: Liu ZJ, Papavramidis TS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Miyauchi A, Kuma K, Matsuzuka F, Matsubayashi S, Kobayashi A, Tamai H, Katayama S. Intrathyroidal epithelial thymoma: an entity distinct from squamous cell carcinoma of the thyroid. World J Surg. 1985;9:128-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cheuk W, Chan JKC, Dorfman DM. Spindle cell tumour with thymus-like differentation. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of endocrine organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2010; 96-97. |

| 3. | Chan JK, Rosai J. Tumors of the neck showing thymic or related branchial pouch differentiation: a unifying concept. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:349-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Reimann JD, Dorfman DM, Nosé V. Carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation of the thyroid (CASTLE): a comparative study: evidence of thymic differentiation and solid cell nest origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:994-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chow SM, Chan JK, Tse LL, Tang DL, Ho CM, Law SC. Carcinoma showing thymus-like element (CASTLE) of thyroid: combined modality treatment in 3 patients with locally advanced disease. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:83-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Da J, Shi H, Lu J. [Thyroid squamous-cell carcinoma showing thymus-like element (CASTLE): a report of eight cases]. Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 1999;21:303-304. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Nakamura Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, Kakudo K. Clinicopathologic significance of intrathyroidal epithelial thymoma/carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation: a collaborative study with Member Institutes of The Japanese Society of Thyroid Surgery. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yamazaki M, Fujii S, Daiko H, Hayashi R, Ochiai A. Carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) with neuroendocrine differentiation. Pathol Int. 2008;58:775-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lam KY, Lo CY, Liu MC. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland: an entity with aggressive clinical behaviour and distinctive cytokeratin expression profiles. Histopathology. 2001;39:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roka S, Kornek G, Schüller J, Ortmann E, Feichtinger J, Armbruster C. Carcinoma showing thymic-like elements--a rare malignancy of the thyroid gland. Br J Surg. 2004;91:142-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luo CM, Hsueh C, Chen TM. Extrathyroid carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) tumor--a new case report and review of literature. Head Neck. 2005;27:927-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |