Published online Oct 10, 2014. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i4.595

Revised: June 6, 2014

Accepted: June 27, 2014

Published online: October 10, 2014

Processing time: 108 Days and 7.4 Hours

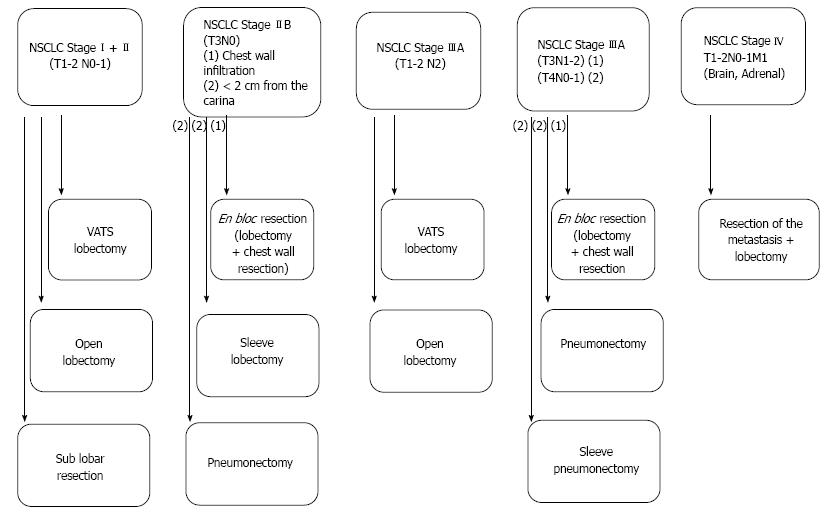

Lung cancer represents the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Despite improvements in preoperative staging, surgical techniques, neoadjuvant/adjuvant options and postoperative care, there are still major difficulties in significantly improving survival, especially in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). To date, surgical resection is the primary mode of treatment for stage I and II NSCLC and has become an important component of the multimodality therapy of even more advanced disease with a curative intention. In fact, in NSCLC patients with solitary distant metastases, surgical interventions have been discussed in the last years. Accordingly, this review displays the recent surgical strategies implemented in the therapy of NSCLC patients.

Core tip: Lung cancer represents the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. To date, surgical resection is the primary mode of treatment for stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and has become an important component of the multimodality therapy of even more advanced disease with a curative intention. In fact, individualized treatment options, based on clinical tumor stages, in NSCLC patients have been established in the last years that are displayed in this review.

- Citation: Al-Shahrabani F, Vallböhmer D, Angenendt S, Knoefel WT. Surgical strategies in the therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5(4): 595-603

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v5/i4/595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v5.i4.595

Lung cancer represents the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, accounting for around 1.4-1.6 million deaths each year[1-4]. While this tumor entity has by far the first place in incidence and mortality among other forms of cancer in males, it is the fourth most frequently malignant tumor in women after breast, cervical and colorectal cancer but it is also the second most common cause of death in the female population[1]. Improving the survival of lung cancer patients is a major challenge for modern multimodality oncological treatment strategies, considering that the 5-year survival remains less than 15% across all stages of disease with fewer than 7% of patients alive 10 years after diagnosis[5]. Even with improvements in preoperative staging, surgical techniques, neoadjuvant/adjuvant options and postoperative care, there are still great difficulties in significantly improving survival, especially in locally advanced disease while early tumor stages theoretically represent the most consistent possibility of modifying the outcome of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)[5]. Indeed, similar to other malignant tumors, the therapy of NSCLC is stage related. At this, surgical resection is the primary mode of treatment for stage I and II NSCLC and an important component of the multimodality approach to stage IIIA disease with a curative intention. Standard resections include removal of the lobe involved with tumor and systematic evaluation of ipsilateral hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Moreover, even in NSCLC patients with solitary distant metastases, surgical interventions have been discussed in the last years. Therefore, the current review displays the recent surgical strategies implemented in the therapy of NSCLC (Figure 1).

Patients with stage I and II NSCLC account for only 25%-30% of all patients presenting with the diagnosis of this malignant tumor[6]. For medically operable patients, lobectomy, the surgical resection of a single lobe, with mediastinal lymph node dissection (MLND) or systematic lymph node sampling (SLNS), is generally accepted as the optimal procedure for this early tumor stage[7,8]. Although the role of surgery has not been validated through randomized trials, the favorable results reported in surgical series and the relative infrequency of long-term survival in patients treated without surgery established this therapeutic approach as the treatment of choice[9,10]. The current literature describes the prognosis for stage I and II NSCLC, undergoing primary surgical resection, expressed in terms of 5-year survival rates, as 60% to 80% for stage I and 30% to 50% for stage II NSCLC[11].

In general, lung resections for NSCLC are performed through a lateral thoracotomy. However, in patients with early stage NSCLC, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) seems to be an acceptable alternative to the well-known open lobectomy in terms of complications and oncological value in patients with early stage NSCLC[12].

In fact, in the last years a number of retrospective studies have shown that VATS lobectomy is associated with fewer complications, and shorter length of hospital stay compared to open surgery[13-20]. These advantages were also described in elderly patients with NSCLC[13,14,19,21-23]. Furthermore, two meta-analyses and two systematic reviews revealed that patients undergoing VATS lobectomy have reduced perioperative morbidity, mortality and less postoperative pain as short-term benefits compared to patients receiving open surgical resection while the long-term results (survival and recurrence rates) were not significantly different between the two surgical procedures[12,22,24,25]. In addition, a recent study by Park et al. with more than 6000 NSCLC patients undergoing either VATS or standard open lobectomy, showed not only that VATS lobectomy had fewer complications (38% vs 44%) and a shorter length of hospital stay (5 d vs 7 d) compared to open surgical resection but rather that patients undergoing VATS at high volume hospitals had a shorter median length of hospital stay (4 d vs 6 d) compared with patients receiving surgical resection at low-volume hospitals[26].

However, the quality and efficiency of the lymphadenectomy (LAD) in NSCLS patients undergoing VATS lobectomy was controversially discussed for a long period of time. A review about 770 patients (VATS: 450 patients, open resection: 320 patients) with cN0-pN2 NSCLC by Watanabe et al. examined the total number of lymph nodes, lymph node stations and mediastinal nodes resected by VATS vs open lobectomy, and found no difference in any of these categories[27]. Moreover, data from the recent American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 trial (n: 752 patients, VATS: 66 patients; open: 686 patients) has also confirmed the efficacy of LAD by the VATS procedure with demonstrating similar number of lymph nodes removed and lymph node stations assessed by both surgical techniques[18].

A point for discussion regarding VATS lobectomy in NSCLC patients might be the issue of smaller resection margins compared to the open procedure, as one might suggest that the extent of the bronchial margin has clinically relevant impact on disease-free and overall survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. However, recent studies showed that the complete surgical resection (R0 resection) but not the extent of the resection margin itself is of prognostic impact[28].

Based on these findings VATS lobectomy is an appropriate surgical technique in the therapy of patients with early stage NSCLC in terms of morbidity, oncological value and survival compared to open surgery[12].

It is generally accepted that the treatment of choice in stage I and II NSCLC patients with low surgical risk is the primary surgical tumor resection by excision of the whole affected lobe. However, especially due to the progress and development in CT imaging, a growing number of ground-glass opacities and small tumors are being detected[29]. Therefore, there is an increasing number of studies dealing with the subject of a sub-lobar resection in such tumor cases. In fact, several retrospective studies have compared sub-lobar resection with complete lobectomy in patients with early NSCLC. For example, in the currently largest study performed by Whitson et al[30], using the American Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, with data from 14.473 patients with stage I tumors treated by anatomical segmentectomy or lobectomy, the prognostic impact of both techniques was assessed. The authors demonstrated that the latter approach provides a statistically significant 5-year survival advantage, even after adjustment for other prognostic factors including tumour size.

Nevertheless, sub-lobar resection might be considered especially in the following patients: (1) Compromised patients that might not tolerate a complete lobectomy; (2) Patients that could tolerate lobectomy but their tumor size itself might not demand a lobectomy.

As data from randomized trials (other than the LCSG trial[31]) is still missing, currently it is not clear if sub-lobar resection is really safe enough in patients with contraindication for lobectomy and if it is associated with equivalent oncological long-term results. Perhaps there are some specific tumor characteristics in that a sub-lobar resection should be recommended in particularly. In addition, another point of discussion is the functional benefit achieved by sub-lobar resection compared to complete lobectomy. Interestingly, studies have shown that the difference in the mean reduction of the post-operative FEV1 and FVC ranges from 5%-6%, respectively 1%-6% (Table 1)[31-33]. As long as it is not proven that the prognostic impact of sub-lobar resection in early stage NSCLC is really equivalent to complete lobectomy, the more invasive procedure should stay the treatment of choice. There are currently 2 randomised controlled trials that may clarify the role of limited resection, i.e., the Cancer and Leukemia Group B 140503 trial (segmentectomy and wedge resection) and the Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0802/West Japan Oncology Group 4607L (segmentectomy) trial[34,35]. In these trials, selection for limited resection includes tumors 2 cm or less in size, peripheral tumors close to the outer third of the lung and good functional status. Finally, sub-lobar resection should preferably be performed by a segment and not by a wedge resection as current data in early stage NSCLC patients revealed that a segment resection is associated with a higher cancer-related survival and lower local recurrence rate compared with a wedge resection[36].

Stage IIB (T3N0M0)

Tumor invasion of the chest wall is an uncommon event in NSCLC with only around 5% of all patients. Interestingly, recent studies suggest that a long term survival rate after surgical en bloc R0 resection of 40%-50% in case of a T3N0M0 tumor stage can be achieved[37]. Similar results (40% five-year survival rate in case of a T3N0 status) have been presented by Doddoli et al[38] in 212 patients with stage IIB tumors. At this, the two most important prognostic factors affecting the survival of this patient subgroup are the complete tumor resection and the pathologic nodal status[39,40].

Stage IIIA (T1-2 N2)

Stage III NSCLC includes a heterogeneous population with disease presentation ranging from apparently resectable tumors with occult microscopic nodal metastases to unresectable bulky nodal disease. Patients with T1-2 pN2 tumor stage can be divided into 3 groups: (1) Patients with an unexpected intraoperative finding of a pN2 stage despite the preoperative staging. The reported incidence of an unexpected N2 lymph node status ranges from 4.7% to 26 %[41-43]. In this subgroup of patients, the surgical resection should be continued, with a lobectomy and LAD. Cerfolio et al[44] reported a 5-year survival rate in patients with unexpected N2 disease who underwent complete resection followed by adjuvant therapy of 35% while patients with single station N2 disease had even a better outcome[44]; (2) Patients with preoperative evidence of N2 disease based on the CT or PET-CT findings and histopathological confirmation. In this group of patients a multimodality therapy is preferable[45]. Interestingly, Ripley and Rusch have recently published a review about the role of induction therapy in NSCLC patients. The authors suggest in this review that a multimodality therapy should be the standard care for stage IIIA (N2) NSCLC patients with resection being offered to patients suitable for complete resection[46]; and (3) Bulky N2 disease. Patients with extensive (bulky) N2 disease should receive a combined radiochemotherapy and only selected cases with good tumor down-sizing should be evaluated for surgical resection However, for this group of patients just little data about the optimal therapy is currently available[47].

Stage IIIA (T3N1-2, T4 N0-1)

In case of a chest wall infiltration (T3) a N2 lymph node status should not be considered as a contraindication for surgical resection in terms of lobectomy with partial chest wall resection and MLND or SLNS. The reported 5-year survival rate after complete resection is 21% in T3N2 disease patients[48].

In case of T4 tumors with invasion of the main carina a sleeve pmeumonectomy can be considered and has become an established procedure in carefully selected patients in experienced centers[49]. While in patients with a complete resection and a post-operative N0 lymph node status the 5-year survival rate ranges between 25%-45%, it is less than 15% in patients with a post-operative N2 disease[50].

Several studies have shown that patients with T1-2 tumors and simultaneously solitary brain or adrenal metastases seem to benefit from a surgical resection[51-55]. This special group of patients can undergo a removal of the solitary brain/adrenal metastasis followed by surgical resection of the primary lung tumor. For example, Read et al[51] revealed in 92 NSCLC patients with solitary brain metastases that the 5-year survival rate after curative resection of the lung tumor and brain metastasis was 21%. Similar data were reported by Billing et al[52] in a retrospective analysis of 28 NSCLC patients with solitary brain metastasis undergoing surgical removal of both tumor locations. Also in NSCLC patients with synchronous solitary adrenal metastasis a surgical treatment with resection of the adrenal and lung mass seems to be beneficial especially for patients with a negative lymph node status[52,54,55].

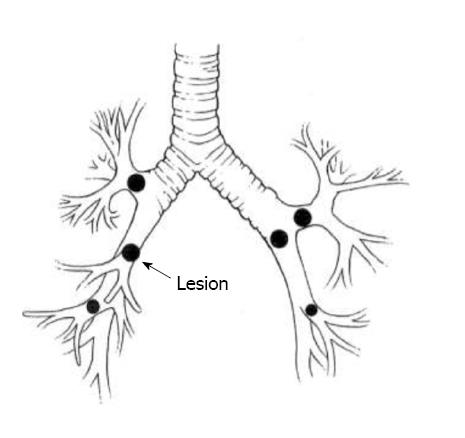

Pneumonectomy has been associated with higher morbidity/mortality and a worse 5-year survival rate after resection for NSCLC, compared to lobectomy or less advanced resection techniques[56-58]. This created the impression that limited anatomical resections in the form of single or double sleeve resections may be beneficial avoiding pneumonectomy related morbidity and mortality. Interestingly, two reviews indicate equivalent survival for patients undergoing either pulmonary sleeve resection or pneumonectomy[59,60]. Furthermore, there was no difference in the recurrence rate but rather a survival benefit for patients with pN0/1 disease undergoing pulmonary sleeve resection. In fact, the most common anatomical locations for bronchoplastic pulmonary resection involve tumors of the right upper lobe and the left upper lobe orifices (Figure 2)[61-63]. At this, the bronchial anastomosis is typically covered using pleura, pedicled pericardial fat or pedicled muscle flap to minimize anastomotic complications[64]. Furthermore, patients undergoing sleeve resection may experience an improved postoperative quality of life compared to patients with a pneumonectomy which was described by Deslauriers et al[65]. Finally, a recent study by Schirren et al[66] showed even in patients with advanced nodal disease no significant advantage for pneumonectomy over sleeve resection.

Although it is generally accepted that lymph node staging of NSCLC should be as accurate as possible, there is ongoing debate regarding the extent of mediastinal lymphadenectomy. Worldwide, surgeons use a variety of techniques including selective sampling (sampling involving only selected suspicious or representative lymph nodes), a SLNS (exploration and biopsy of a standard set of lymph node stations in each case) and MLND, which involves the removal of all node-bearing tissue within defined landmarks for a standard set of lymph node stations[67]. As data have shown that the accuracy of staging in NSCLC patients is more effective with either MLND or SLNS compared with selective sampling alone[68-70], existing guidelines recommend either one of the methods at the time of surgical resection. Studies have shown that MLND leads to a significant reduction of local and systemic recurrence[71,72]. Furthermore, another potential advantage of MLND is a more accurate tumor staging through the detection of skip- and micro-metastases[71,73-75]. Nevertheless, some researchers argue that the improved outcome after MLND is in fact just a stage migration phenomenon (“Will Rogers phenomenon”)[76,77]. In a retrospective study by Doddoli et al[72] the effect of MLND vs SLNS on overall survival of patients with stage I NSCLC was assessed and the working group demonstrated that MLND was a favorable independent prognostic factor. Similar results were reported by Lardinois et al[71] showing a longer disease-free survival in stage I NSCLC patients who underwent MLND vs SLNS (60.2 ± 7 vs 44.8 ± 8.1 mo).

It is hypothesized that the need for extended resection in patients with locally advanced NSCLC is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality rate. However, evidence suggests that the mortality rate is not significantly increased after extended resections[78]. For example, Izbicki et al[78] showed in patients undergoing extended resection for stage T3 or T4 NSCLC tumors that the study patients with no residual tumor had a 3-year survival rate of 33%. In addition, Spaggiari et al[79] reported a 3-year probability of survival of 39% after extended pneumonectomy with partial resection of the left atrium for advanced lung cancer. Even a study from Hillinger et al[80] revealed that patients with T4 tumors (infiltration of great vessels, trachea, esophagus, vertebral bodies, etc.) showed an increasing 5-year survival rate from 15 to 35% after radical resection with acceptable preoperative mortality if treated in experienced centres. Extended surgical resections seems also appropriate for patients with locally advanced lung cancer with limited invasion of the carina, left atrium, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery[81]. Furthermore, in case of advanced tumor removals with the need of additional pulmonary resection, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support is a considered to be a safe alternative to cardiopulmonary bypass after pneumonectomy or even carina resection after pneumonectomy[82,83]. In the event of a tumor infiltration into the pulmonary artery, a major anatomical lung resection with angioplastic procedures may achieve a similar oncological radicality with sparing distal lung parenchyma. The long term outcomes in these cases are significantly influenced by the nodal status and are comparable to those of conventional lobectomy[84,85]. Therefore, lung resections with bronchovascular reconstruction are invaluable for patients with central tumours, although they do demand more skill than pneumonectomies. The acceptable clinical results and oncological reliability promote this type of interventions, which always have to be considered for any central tumour in order to avoid pneumonectomy and its complications[86].

Thoracic surgery is a dynamic field with many scientific and technical changes occurred in the last years. A prominent example is the use of less invasive approaches for major resection of NSCLC patients. In fact, it has been proven in early stage NSCLC patients that VATS lobectomy as a routinely performed technical procedure is a method with equal or even better long-term results compared to the well-established open surgical resection.

Sub-lobar resection has its value in the surgical therapy of NSCLC patients with limited lung function. Especially for patients with decreased pulmonary function or comorbid disease and clinical stage I NSCLC a sub-lobar resection should have priority over a conservative treatment. Possible criteria for sub lobar lung resection in early stage NSCLC patients seem to be: (1) limited lung function; (2) tumor diameter ≤ 2 cm; (3) N0 lymph node status; and (4) Frozen section with tumor free edge resection. In case of a sub-lobar resection, segmentectomy should always be preferred rather than a wedge resection. However, a lot of reports about sub-lobar resection combine segmental and wedge resection which seems in our opinion not appropriate as segmentectomy offers the potential advantage of complete resection of lymphatic and vascular drainage.

The ongoing debate about the efficacy of LAD during VATS lobectomy originates mainly from the lack of strict technical standards. The guidelines of the American National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend the complete dissection of at least three mediastinal lymph node stations[87]. The European Society for Thoracic Surgery (ESTS) has published similar guidelines advising the removal of at least three lymph node stations including the subcarinal station[88].

Another issue is the debate about the role of radiation therapy in postoperative N2 disease. Even though some studies suggest that postoperative radiation in case of N2 disease can improve local control, it remains controversial whether it has a prognostic effect[89]. Based on the National Cancer Institute of Canada and Intergroup Study, the postoperative radiation may be considered in selected patients to reduce the risk of local recurrence, if any of the following are present: (1) involvement of multiple nodal stations; (2) extracapsular tumor spread[90].

Finally, multimodality treatment options have been implemented for patients with locally advanced or limited metastatic disease offering more patients a potential complete surgical tumor resection as the operative therapy remains the most important and successful option to really cure NSCLC patients.

P- Reviewer: Garfield DH, Huang SA, Rosell R, Sugawara I S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in RCA: 11834] [Article Influence: 845.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Brawley OW. Avoidable cancer deaths globally. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:67-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:792-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374-1403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Crinò L, Weder W, van Meerbeeck J, Felip E. Early stage and locally advanced (non-metastatic) non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v103-v115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scott WJ, Howington J, Feigenberg S, Movsas B, Pisters K. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer stage I and stage II: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132:234S-242S. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mazzone P. Preoperative evaluation of the lung resection candidate. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79 Electronic Suppl 1:eS17-eS22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gorenstein LA, Sonett JR. The surgical management of stage I and stage II lung cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2011;20:701-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Manser R, Wright G, Hart D, Byrnes G, Campbell DA. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD004699. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Raz DJ, Zell JA, Ou SH, Gandara DR, Anton-Culver H, Jablons DM. Natural history of stage I non-small cell lung cancer: implications for early detection. Chest. 2007;132:193-199. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tanoue LT, Detterbeck FC. New TNM classification for non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:413-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, McCaughan BC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2553-2562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cattaneo SM, Park BJ, Wilton AS, Seshan VE, Bains MS, Downey RJ, Flores RM, Rizk N, Rusch VW. Use of video-assisted thoracic surgery for lobectomy in the elderly results in fewer complications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:231-235; discussion 231-235;. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Port JL, Mirza FM, Lee PC, Paul S, Stiles BM, Altorki NK. Lobectomy in octogenarians with non-small cell lung cancer: ramifications of increasing life expectancy and the benefits of minimally invasive surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1951-1957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Whitson BA, Andrade RS, Boettcher A, Bardales R, Kratzke RA, Dahlberg PS, Maddaus MA. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is more favorable than thoracotomy for resection of clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1965-1970. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Flores RM, Park BJ, Dycoco J, Aronova A, Hirth Y, Rizk NP, Bains M, Downey RJ, Rusch VW. Lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) versus thoracotomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Villamizar NR, Darrabie MD, Burfeind WR, Petersen RP, Onaitis MW, Toloza E, Harpole DH, D’Amico TA. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity compared with thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Scott WJ, Allen MS, Darling G, Meyers B, Decker PA, Putnam JB, McKenna RW, Landrenau RJ, Jones DR, Inculet RI. Video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open lobectomy for lung cancer: a secondary analysis of data from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0030 randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:976-981; discussion 981-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ilonen IK, Räsänen JV, Knuuttila A, Salo JA, Sihvo EI. Anatomic thoracoscopic lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer in stage I is associated with less morbidity and shorter hospitalization than thoracotomy. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:1126-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Handy JR, Asaph JW, Douville EC, Ott GY, Grunkemeier GL, Wu Y. Does video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer provide improved functional outcomes compared with open lobectomy? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:451-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Berry MF, Hanna J, Tong BC, Burfeind WR, Harpole DH, D’Amico TA, Onaitis MW. Risk factors for morbidity after lobectomy for lung cancer in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1093-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cheng D, Downey RJ, Kernstine K, Stanbridge R, Shennib H, Wolf R, Ohtsuka T, Schmid R, Waller D, Fernando H. Video-assisted thoracic surgery in lung cancer resection: a meta-analysis and systematic review of controlled trials. Innovations (Phila). 2007;2:261-292. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Detterbeck F. Thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy debate: the pro argument. Thorac Surg Sci. 2009;6:Doc04. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | West D, Rashid S, Dunning J. Does video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy produce equal cancer clearance compared to open lobectomy for non-small cell carcinoma of the lung? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:110-116. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Whitson BA, Groth SS, Duval SJ, Swanson SJ, Maddaus MA. Surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review of the video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus thoracotomy approaches to lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:2008-2016; discussion 2008-2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Park HS, Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW. Impact of hospital volume of thoracoscopic lobectomy on primary lung cancer outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:372-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Watanabe A, Mishina T, Ohori S, Koyanagi T, Nakashima S, Mawatari T, Kurimoto Y, Higami T. Is video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery a feasible approach for clinical N0 and postoperatively pathological N2 non-small cell lung cancer? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:812-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tomaszek SC, Kim Y, Cassivi SD, Jensen MR, Shen KH, Nichols FC, Deschamps C, Wigle DA. Bronchial resection margin length and clinical outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1151-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, Balekian AA, Murthy SC. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e278S-e313S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 976] [Article Influence: 81.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Whitson BA, Groth SS, Andrade RS, Maddaus MA, Habermann EB, D’Cunha J. Survival after lobectomy versus segmentectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a population-based analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1943-1950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:615-622; discussion 622-623. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Keenan RJ, Landreneau RJ, Maley RH, Singh D, Macherey R, Bartley S, Santucci T. Segmental resection spares pulmonary function in patients with stage I lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:228-233; discussion 228-233. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Harada H, Okada M, Sakamoto T, Matsuoka H, Tsubota N. Functional advantage after radical segmentectomy versus lobectomy for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:2041-2045. [PubMed] |

| 34. | CALGB 140503. A phase III randomised trial of lobectomy versus sublobar resection for small (≤2 cm) peripheral non-small cell lung cancer. Available from: http://www.calgb.org/public/Meetings/presentations/2007/cra_ws/03-140501-Altorki062007.pdf.Accessed Apr 22, 2013. |

| 35. | Nakamura K, Saji H, Nakajima R, Okada M, Asamura H, Shibata T, Nakamura S, Tada H, Tsuboi M. A phase III randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for small-sized peripheral non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:271-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sienel W, Dango S, Kirschbaum A, Cucuruz B, Hörth W, Stremmel C, Passlick B. Sublobar resections in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer: segmentectomies result in significantly better cancer-related survival than wedge resections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:728-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Stoelben E, Ludwig C. Chest wall resection for lung cancer: indications and techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:450-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Doddoli C, D’Journo B, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, Dujon A, Foucault C, Thomas P, Riquet M. Lung cancer invading the chest wall: a plea for en-bloc resection but the need for new treatment strategies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:2032-2040. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Sanli A, Onen A, Yücesoy K, Karaçam V, Karapolat S, Gökçen B, Eyüboğlu GM, Demiral A, Oztop I, Açikel U. [Surgical treatment in non-small cell lung cancer invading to the chest wall (T3) and vertebra (T4)]. Tuberk Toraks. 2007;55:383-389. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Deslauriers J, Tronc F, Fortin D. Management of tumors involving the chest wall including pancoast tumors and tumors invading the spine. Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23:313-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Goldstraw P, Mannam GC, Kaplan DK, Michail P. Surgical management of non-small-cell lung cancer with ipsilateral mediastinal node metastasis (N2 disease). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:19-27; discussion 27-8. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Eloubeidi MA. Routine mediastinoscopy and esophageal ultrasound fine-needle aspiration in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who are clinically N2 negative: a prospective study. Chest. 2006;130:1791-1795. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Al-Sarraf N, Aziz R, Gately K, Lucey J, Wilson L, McGovern E, Young V. Pattern and predictors of occult mediastinal lymph node involvement in non-small cell lung cancer patients with negative mediastinal uptake on positron emission tomography. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:104-109. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS. Survival of patients with unsuspected N2 (stage IIIA) nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:362-366; discussion 362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Robinson LA, Ruckdeschel JC, Wagner H, Stevens CW. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer-stage IIIA: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132:243S-265S. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Ripley RT, Rusch VW. Role of induction therapy: surgical resection of non-small cell lung cancer after induction therapy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23:273-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | VAN Schil PE, Waele MD, Hendrik JM, Lauwers PR. Is there a role for surgery in stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer? Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2008;11:615-621. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Magdeleinat P, Alifano M, Benbrahem C, Spaggiari L, Porrello C, Puyo P, Levasseur P, Regnard JF. Surgical treatment of lung cancer invading the chest wall: results and prognostic factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1094-1099. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Aigner C, Lang G, Klepetko W. Sleeve pneumonectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;18:109-113. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Alifano M, Regnard JF. Sleeve pneumonectomy. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;2007:mmcts.2006.002113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Read RC, Boop WC, Yoder G, Schaefer R. Management of nonsmall cell lung carcinoma with solitary brain metastasis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;98:884-890; discussion 890-891. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Billing PS, Miller DL, Allen MS, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC. Surgical treatment of primary lung cancer with synchronous brain metastases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:548-553. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Porte H, Siat J, Guibert B, Lepimpec-Barthes F, Jancovici R, Bernard A, Foucart A, Wurtz A. Resection of adrenal metastases from non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:981-985. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Pfannschmidt J, Schlolaut B, Muley T, Hoffmann H, Dienemann H. Adrenalectomy for solitary adrenal metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;49:203-207. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Mordant P, Arame A, De Dominicis F, Pricopi C, Foucault C, Dujon A, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, Riquet M. Which metastasis management allows long-term survival of synchronous solitary M1b non-small cell lung cancer? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:617-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Licker M, Spiliopoulos A, Frey JG, Robert J, Höhn L, de Perrot M, Tschopp JM. Risk factors for early mortality and major complications following pneumonectomy for non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. Chest. 2002;121:1890-1897. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Powell ES, Pearce AC, Cook D, Davies P, Bishay E, Bowler GM, Gao F. UK pneumonectomy outcome study (UKPOS): a prospective observational study of pneumonectomy outcome. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Mansour Z, Kochetkova EA, Santelmo N, Meyer P, Wihlm JM, Quoix E, Massard G. Risk factors for early mortality and morbidity after pneumonectomy: a reappraisal. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1737-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Ferguson MK, Lehman AG. Sleeve lobectomy or pneumonectomy: optimal management strategy using decision analysis techniques. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1782-1788. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Ma Z, Dong A, Fan J, Cheng H. Does sleeve lobectomy concomitant with or without pulmonary artery reconstruction (double sleeve) have favorable results for non-small cell lung cancer compared with pneumonectomy? A meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:20-28. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Ludwig C, Stoelben E, Olschewski M, Hasse J. Comparison of morbidity, 30-day mortality, and long-term survival after pneumonectomy and sleeve lobectomy for non-small cell lung carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:968-973. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Merritt RE, Mathisen DJ, Wain JC, Gaissert HA, Donahue D, Lanuti M, Allan JS, Morse CR, Wright CD. Long-term results of sleeve lobectomy in the management of non-small cell lung carcinoma and low-grade neoplasms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1574-1581; discussion 1574-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Takeda S, Maeda H, Koma M, Matsubara Y, Sawabata N, Inoue M, Tokunaga T, Ohta M. Comparison of surgical results after pneumonectomy and sleeve lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer: trends over time and 20-year institutional experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:276-280. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Wright CD. Sleeve lobectomy in lung cancer. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;18:92-95. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Deslauriers J, Grégoire J, Jacques LF, Piraux M, Guojin L, Lacasse Y. Sleeve lobectomy versus pneumonectomy for lung cancer: a comparative analysis of survival and sites or recurrences. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1152-1156; discussion 1156. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Schirren J, Schirren M, Passalacqua M, Bölükbas S. [Pneumonectomy: an alternative to sleeve resection in lung cancer patients?]. Chirurg. 2013;84:474-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Rami-Porta R, Wittekind C, Goldstraw P. Complete resection in lung cancer surgery: proposed definition. Lung Cancer. 2005;49:25-33. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Allen MS, Darling GE, Pechet TT, Mitchell JD, Herndon JE, Landreneau RJ, Inculet RI, Jones DR, Meyers BF, Harpole DH. Morbidity and mortality of major pulmonary resections in patients with early-stage lung cancer: initial results of the randomized, prospective ACOSOG Z0030 trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1013-109; discussion 1013-109;. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Gaer JA, Goldstraw P. Intraoperative assessment of nodal staging at thoracotomy for carcinoma of the bronchus. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4:207-210. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Wu Yl, Huang ZF, Wang SY, Yang XN, Ou W. A randomized trial of systematic nodal dissection in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;36:1-6. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Lardinois D, Suter H, Hakki H, Rousson V, Betticher D, Ris HB. Morbidity, survival, and site of recurrence after mediastinal lymph-node dissection versus systematic sampling after complete resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:268-274; discussion 274-275. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Doddoli C, Aragon A, Barlesi F, Chetaille B, Robitail S, Giudicelli R, Fuentes P, Thomas P. Does the extent of lymph node dissection influence outcome in patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:680-685. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Izbicki JR, Passlick B, Hosch SB, Kubuschock B, Schneider C, Busch C, Knoefel WT, Thetter O, Pantel K. Mode of spread in the early phase of lymphatic metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer: significance of nodal micrometastasis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:623-630. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Izbicki JR, Passlick B, Karg O, Bloechle C, Pantel K, Knoefel WT, Thetter O. Impact of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy on tumor staging in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:209-214. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Izbicki JR, Thetter O, Habekost M, Karg O, Passlick B, Kubuschok B, Busch C, Haeussinger K, Knoefel WT, Pantel K. Radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg. 1994;81:229-235. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Izbicki JR, Passlick B, Pantel K, Pichlmeier U, Hosch SB, Karg O, Thetter O. Effectiveness of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: results of a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1998;227:138-144. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604-1608. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Izbicki JR, Knoefel WT, Passlick B, Habekost M, Karg O, Thetter O. Risk analysis and long-term survival in patients undergoing extended resection of locally advanced lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:386-395. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Spaggiari L, D’ Aiuto M, Veronesi G, Pelosi G, de Pas T, Catalano G, de Braud F. Extended pneumonectomy with partial resection of the left atrium, without cardiopulmonary bypass, for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:234-240. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Hillinger S, Weder W. Extended surgical resection in stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Front Radiat Ther Oncol. 2010;42:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | DiPerna CA, Wood DE. Surgical management of T3 and T4 lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5038s-5044s. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Lang G, Taghavi S, Aigner C, Charchian R, Matilla JR, Sano A, Klepetko W. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for resection of locally advanced thoracic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:264-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lei J, Su K, Li XF, Zhou YA, Han Y, Huang LJ, Wang XP. ECMO-assisted carinal resection and reconstruction after left pneumonectomy. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Kojima F, Yamamoto K, Matsuoka K, Ueda M, Hamada H, Imanishi N, Miyamoto Y. Factors affecting survival after lobectomy with pulmonary artery resection for primary lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:e13-e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Galetta D, Veronesi G, Leo F, Spaggiari L. Pulmonary artery reconstruction by a custom-made heterologous pericardial conduit in the treatment of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:241-243. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Gómez-Caro A. [Broncho-angioplasty surgery in the treatment of lung cancer]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2009;45:531-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Bepler G, Blum MG, Chang A, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, D’Amico TA, Demmy TL, Ganti AK. Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:740-801. [PubMed] |

| 88. | Lardinois D, De Leyn P, Van Schil P, Porta RR, Waller D, Passlick B, Zielinski M, Lerut T, Weder W. ESTS guidelines for intraoperative lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:787-792. [PubMed] |

| 89. | PORT Meta-analysis Trialists Group. Postoperative radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD002142. [PubMed] |

| 90. | Pepe C, Hasan B, Winton TL, Seymour L, Graham B, Livingston RB, Johnson DH, Rigas JR, Ding K, Shepherd FA. Adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin in elderly patients: National Cancer Institute of Canada and Intergroup Study JBR.10. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1553-1561. [PubMed] |

| 91. | Faber LP. Sleeve resections for lung cancer. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;5:238-248. [PubMed] |