Published online May 10, 2014. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.103

Revised: December 24, 2013

Accepted: March 17, 2014

Published online: May 10, 2014

Processing time: 179 Days and 18.2 Hours

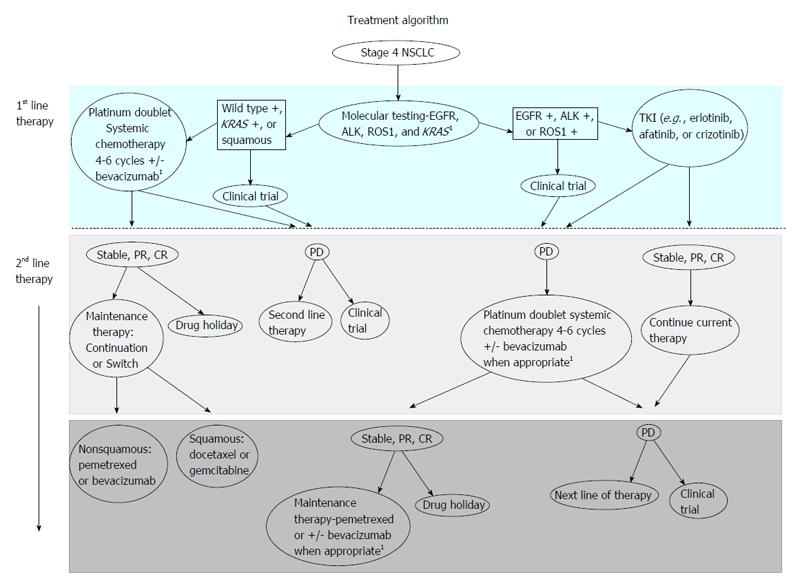

The purpose of this article is to review the role of maintenance therapy in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A brief overview about induction chemotherapy and its primary function in NSCLC is provided to address the basis of maintenance therapies foundation. The development of how maintenance therapy is utilized in this population is discussed and current guidelines for maintenance therapy are reviewed. Benefits and potential pitfalls of maintenance therapy are addressed, allowing a comprehensive review of the achieved clinical benefit that maintenance therapy may or may not have on NSCLC patient population. A review of current literature was conducted and a table is provided comparing the results of various maintenance therapy clinical trials. The table includes geographical location of each study, the number of patients enrolled, progression free survival and overall survival statistics, post-treatment regimens and if molecular testing was conducted. The role of molecular testing in relation to therapeutic treatment options for advanced NSCLC patients is discussed. A treatment algorithm clearly depicts first line and second line treatment for management of NSCLC and includes molecular testing, maintenance therapy and the role clinical trials have in treatment of NSCLC. This treatment algorithm has been specifically tailored and developed to assist clinicians in the management of advanced NSCLC.

Core tip: This review article addresses the role of maintenance therapy in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Maintenance therapy utilization in NSCLC patient population and review of current guidelines for maintenance therapy are discussed. A treatment algorithm was created to depict first line and second line treatment for managing NSCLC and includes molecular testing, maintenance therapy, and the role of clinical trials in the treatment of NSCLC. A comprehensive review of the achieved clinical benefit that maintenance therapy may or may not have on the NSCLC patient population is presented.

- Citation: Dearing KR, Sangal A, Weiss GJ. Maintaining clarity: Review of maintenance therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5(2): 103-113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v5/i2/103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.103

Lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related death in men and women worldwide and attributes approximately 1.37 million deaths per year worldwide[1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common form of lung cancer and approximately 2/3 of patients with NSCLC present with advanced disease[2]. This advanced disease state leads to limited treatment options[3], primarily systemic therapy. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, 4-6 cycles of platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is recommend as first-line treatment in patients without a driver mutation, such as, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement[4]. For those patients with an EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement, use of a specific inhibitor directed at that target is indicated either as the initial treatment or as therapy when progressive disease develops.

The platinum doublet generally consists of cisplatin or carboplatin with another cytotoxic agent, sometimes in combination with a biologic agent such as bevacizumab (B). Multiple cytotoxic agents in addition to cisplatin and carboplatin have antitumor activity in NSCLC. These include pemetrexed, taxanes (docetaxel, paclitaxel, nanoparticle albumin bound paclitaxel), gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and camptothecins (irinotecan, topotecan). The use of cytotoxic chemotherapy as the initial treatment for patients not selected based upon EGFR mutation status and for those whose tumors do not contain an EGFR mutation is supported by the results of the tarceva or chemotherapy trial[5]. In that trial, 760 patients were randomly assigned to either first-line erlotinib followed by chemotherapy (cisplatin plus gemcitabine) upon progression or the same first-line chemotherapy followed by erlotinib upon progression. Overall survival (OS) was significantly longer in unselected patients assigned to initial chemotherapy followed by second-line erlotinib (median 11.6 mo vs 8.7 mo, HR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.04-1.47). For patients known to be EGFR mutation negative, OS was significantly longer with initial chemotherapy (median 9.6 mo vs 6.5 mo). Combination chemotherapy regimens using a platinum doublet result in median OS of 8-11 mo[3].

Extending the duration of treatment with the initial platinum based chemotherapy beyond four to six cycles has been evaluated. Currently, there is little evidence to support continuous doublet cytotoxic chemotherapy after 4-6 cycles being given until disease progression[6], although longer treatment duration increases progression-free survival (PFS), it has at most only a modest effect on OS[7]. Maintenance therapy is an extension of induction chemotherapy and is continued for a determined period of time unless there is disease progression or significant toxicities develop[8]. The goal is to extend a favorable patient response from first-line platinum based combination chemotherapy[9]. There are two types of maintenance therapy, known as continuation and switch maintenance therapy. Continuation maintenance therapy is the administration of one chemotherapy agent that was part of the initial chemotherapy regimen. Continuation maintenance therapy can involve either a non-platinum cytotoxic drug or a molecular targeted agent. Switch maintenance therapy, involves administration of a new chemotherapy agent that was not part of the original chemotherapy regimen and a potentially non-cross-resistant agent that is started immediately after completion of first-line induction chemotherapy[9]. Currently, switch-maintenance therapy with pemetrexed or erlotinib is food and drug administration (FDA)-approved. With the standard 4-6 cycles of platinum based chemotherapy, patients may have a response within the first 2-4 cycles; however, many patients cannot tolerate long-term treatment[10]. Disease progression and co-morbidities that arise due to disease progression contribute to the intolerance of long-term treatment.

Historically, treatment for advanced NSCLC involved waiting until disease progression before a second-line therapy was started[8]. After first-line therapy, “drug holidays” rarely lasting more than 3 mo in duration can pose a risk for rapid clinical deterioration leading to ineligibility for second-line treatment[11,12]. This led to clinical trials investigating the role for maintenance therapy using 3rd generation cytotoxic agents and targeted therapy[8]. Many of these studies either did not have adequate power to detect statistical significance for survival benefits or did not have a placebo control arm[8].

Advocates of maintenance therapy point to potential merits including: higher probability that tumor will be exposed to effective therapies, decreased development of chemotherapy resistance, maximizing the efficacy of chemotherapy, potentiating the anti-angiogenic effects of chemotherapy, and enhancing anti-tumor immunostimulation[9]. Many patients do not go on to receive second-line therapy due to rapid progression of disease, decrease in their performance status, or increase cancer-related symptoms. By treating patients with maintenance therapy, the window of opportunity for treatment may be extended. Those patients that benefit from maintenance therapy have better performance status and responded to first-line therapy[9].

Critics of maintenance therapy argue that the trials evaluating maintenance therapy have: inconsistent clinical trial endpoints, impose a detrimental effect on quality of life, prevent some patients from having a drug holiday, add increased associated costs[9], and eliminate from the armamentarium standard second-line chemotherapy agents if they are used as maintenance therapy. Patients on maintenance chemotherapy with stable disease may also be exposed to additional toxicities[6] although some maintenance therapies like pemetrexed have limited grade 3-4 toxicities, such as fatigue and neutropenia[8], and may be better tolerated.

There are currently five medications that are United States FDA approved for maintenance therapy in NSCLC (B, cetuximab, pemetrexed, gemcitabine, and erlotinib)[4]. Data exist on some agents that perform better or worse based on tumor histology. For example, regimens containing pemetrexed are more effective in patients with adenocarcinoma and have not demonstrated a meaningful clinical benefit for patients with squamous cell carcinoma. The impact of histology was illustrated by a phase III trial in which cisplatin plus pemetrexed was compared with cisplatin plus gemcitabine as initial therapy[13,14]. Survival in the 847 patients with adenocarcinoma was significantly prolonged with cisplatin plus pemetrexed compared to cisplatin plus gemcitabine (median 12.6 mo vs 10.9 mo, P = 0.03). Conversely, cisplatin plus gemcitabine was superior to cisplatin plus pemetrexed in the 473 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (median 10.8 mo vs 9.4 mo, P = 0.05). Ultimately, the outcome from this study and review of previous trial data led to the re-labeling of pemetrexed for use in non-squamous NSCLC.

A list with pertinent details of large randomized maintenance therapy trials in NSCLC is provided in Table 1.

| Maintenance | PFS (mo) | HR | P | 95%CI | PFS + induction | HR | P | 95%CI | OS (mo) | HR | P | 95%CI | OS + induction (mo) | HR | P | 95%CI | Genotype | Post-TX | |

| Vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 q weekly | × 6 m until PD | 5.0 | NR | 12.3 | NR | NC | Etoposide 80 mg/m2, cisplatin 30 mg/m2 | ||||||||||||

| vs | NR | NR | NR | NR | 12.3 | 1.08 | 0.65 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||||

| Observation | 3.0 | 0.77 | 0.110 | 0.56-1.07 | |||||||||||||||

| Gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 q21 d | Until PD/ removal request | 3.6 (TTP) | 6.6 (TTP + induction) | 10.2 | 13.0 | NC | Second line chemotherapy/ radiation | ||||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| BSC | 2.0 (TTP) | 0.70 | 0.001 | 0.50-0.90 | 5.0 (TTP + induction) | 0.70 | 0.001 | 0.50-0.90 | 8.1 | 0.172 | 11.0 | NR | 0.195 | ||||||

| Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg q3 wk | Until PD | 6.2 | 0.66 | 0.001 | 0.57-0.77 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 12.3 | 0.79 | 0.003 | 0.67-0.92 | NR | NR | NR | |||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Observation | 4.5 | NR | 10.3 | NR | NC | None reported | |||||||||||||

| Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 q21 d | Until PD | 4.3 | 7.7 | 13.4 | 16.5 | NC | Pemetrexed, docetaxel, erlotinib, gefitinib, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, carboplatin, cisplatin, paclitaxel | ||||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Placebo | 2.6 | 0.50 | 0.0001 | 0.42-0.61 | 5.9 | 0.50 | 0.0001 | 0.42-0.61 | 10.6 | 0.79 | 0.012 | 0.65-0.95 | 13.9 | 0.79 | 0.012 | 0.65-0.95 | |||

| Immediate docetaxel 75 mg/m2 q21 d | × 6 cycles | 5.7 | NR | 12.3 | NR | NR | NC | Best supportive care, observed for PD/ survival | |||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Delayed docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (start at PD) q21 d | 2.7 | NR | 0.0001 | 2.60-2.90 m | NR | NR | NR | NR | 9.7 | NR | 0.853 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Pemetrexed 500 mg/kg + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg q21 d | Until PD or discontinued | 6.0 | 8.6 | 12.6 | 17.7 | NR | Collected-no specific results | None reported | |||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg q21 d | Until PD or discontinued | 5.6 | 0.83 | 0.012 | 0.70-0.96 | 6.9 | NR | NR | NR | 13.4 | 1.00 | 0.949 | 15.7 | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Cetuxamab 250 mg/m2 weekly | Until PD/ toxicities | 4.8 | 0.94 | 0.390 | 0.82-1.07 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.3 | 0.87 | 0.044 | 0.76-0.99 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Collected- EGFR (IHC) | None reported |

| Observation | 4.8 | 10.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Bevacizumab 7.5 mg/m2 | Until PD | 6.7 | 0.75 | 0.003 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Not sufficient | NR | NR | NR | NR | NC | No bevacizumab | ||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bevacizumab 15 mg/m2 | 6.5 | 0.82 | 0.030 | ||||||||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Placebo | 6.1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Erlotinib 150 mg/d | Until PD/ toxicities/ death | 4.1 | NR | NR | 12.0 | NR | NR | EGFR/wild type/ resistance mutations | Erlotinib (people in placebo group that were egfr +, taxanes (+ docetaxel), antimetabolics (+ pemetrexed), platinums, antineoplastics | ||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Placebo | 2.75 | 0.71 | 0.0001 | 0.62-0.82 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.0 | 0.81 | 0.009 | 0.70-0.95 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Cetuximab 250 mg/m2 weekly | Until PD/ toxicities | 4.4 | 0.90 | 0.236 | 0.76-1.06 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 9.6 | 0.89 | 0.169 | 0.75-1.05 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Not included in study | None reported |

| Observation | 4.2 | 8.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 q3 wk | Until PD | 4.1 | 6.9 | 13.9 | 16.9 | NC | Erlotinib, docetaxel, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, cisplatin, bevacizumab, investigational drug | ||||||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Placebo | 2.8 | 0.62 | 0.0001 | 0.49-0.79 | 5.6 | 0.59 | 0.0001 | 0.47-0.74 | 11.0 | 0.78 | 0.020 | 0.64-0.96 | 14.0 | 0.78 | 0.019 | 0.64-0.96 | |||

| Gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 q3 wk | Until PD/ toxicity/death | 3.0 | 0.56 | 0.001 | 0.44-0.72 | NR | 12.1 | 0.89 | 0.387 | 15.2 | 0.72 | NS | EGFR mutations/ expressions (exon 19 deletions, mutations in exon 21 and L858R point mutations) | Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 q21 d, erlotinib, docetaxel | |||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Erlotinib 150 mg/d q3 wk | Until PD/ toxicity/death | 2.9 | 0.69 | 0.003 | 0.54-0.88 | NR | 11.4 | 0.87 | 0.304 | NR | NR | ||||||||

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Observation | 1.9 | NR | 10.0 | 10.8 | |||||||||||||||

| Pemetrexed 500 mg/kg + bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg q3 wk | Until PD | 7.4 | 0.48 | 0.001 | 0.35-0.66 | 10.2 | 0.50 | 0.001 | 0.37-0.69 | NR | 0.75 | 0.219 | 0.47-1.19 | NR | 0.75 | 0.230 | 0.47-1.20 | NC | Taxanes/TKI |

| vs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bevacizumab 7.5 mg/m2 q3 wk | Until PD | 3.7 | 6.6 | 12.8 | 15.0 |

In a study published in 2005, vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 was evaluated as a maintenance therapy given weekly for 6 mo until disease progression compared with observation alone in stage IIIB/IV NSCLC patients after induction with MIC treatment (mitomycin 6 mg/m2, ifosfamide 1.5 mg/m2, cisplatin 30 mg/m2 given every four wk × 2-4 cycles ± radiotherapy)[15]. A total of 91 patients were randomized to vinorelbine maintenance therapy. Median PFS for vinorelbine was 5 mo vs 3 mo with observation, but the difference was not statistically significant. Median OS for both groups were the same at 12.3 mo and evaluation of molecular subtypes were not performed.

A phase III trial evaluating continuation maintenance therapy with gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 every 3 wk until disease progression or request for removal vs best supportive care (BSC) was reported[2]. Advanced NSCLC patients were given gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 and cisplatin 80 mg/m2 every 3 wk for 4 cycles as an induction regimen. Two hundred six patients were given gemcitabine while 138 patients received BSC alone. Median time to progression (TTP) from induction was measured and was a median of 6.6 mo with gemcitabine vs 5 mo with BSC (P < 0.001, HR = 0.7, 95%CI: 0.5-0.9). Median OS from induction for gemcitabine was 13 mo compared to 11 mo, but not significantly different (P = 0.195). Karnofsky performance status (KPS) was taken into consideration with OS and patients were split into KPS > 80 vs KPS ≤ to 80. Patients with KPS > 80 had a HR = 2.1 of dying while on gemcitabine and patients with KPS ≤ to 80 had HR = 0.8. Using continuation maintenance therapy with gemcitabine after induction with gemcitabine and cisplatin did demonstrate a longer TTP vs BSC for patients with advanced NSCLC. No molecular testing was conducted in this study.

The Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) 4599 study evaluated the effectiveness of B maintenance therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC nonsquamous histology only[16]. Patients completed carboplatin 6 mg/mL AUC and paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 induction chemotherapy every three weeks for six cycles or carboplatin 6 mg/mL AUC, paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 and B 15 mg/kg every three weeks for six cycles. Patients were randomized to B 15 mg/kg maintenance therapy or surveillance (only patients without progressive disease after induction therapy were eligible for this arm). Median PFS was significantly higher for B vs surveillance at 6.2 mo vs 4.5 mo (P < 0.001). Median OS was significantly higher for B vs surveillance at 12.3 mo vs 10.3 mo (P = 0.003). No tumor molecular testing was completed for this study.

In 2009, the JMEN study, an international randomized, double-blind, phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed with BSC vs placebo plus BSC for NSCLC resulted in pemetrexed being approved by the FDA for use as maintenance therapy in NSCLC[10]. Patients were treated with one of six induction regimens (gemcitabine-carboplatin, gemcitabine-cisplatin, paclitaxel-carboplatin, paclitaxel-cisplatin, docetaxel-carboplatin or docetaxel-cisplatin) every 3 wk for four cycles. Patients were assigned randomized 2:1 to receive pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or placebo. Median PFS plus induction was 7.7 mo for pemetrexed vs 5.9 mo for placebo (P < 0.0001, HR = 0.50, 95%CI: 0.42-0.61). Median OS plus induction was 16.5 mo with pemetrexed vs 13.9 mo with placebo (P = 0.012, HR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.65-0.95). Overall, switch maintenance therapy with pemetrexed demonstrated improved PFS and OS and was well-tolerated. In this study, no tumor tissue molecular testing was conducted.

In a phase III study of advanced NSCLC patients receiving induction therapy with gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 and carboplatin AUC = 5 every 21 d for four cycles, patients that did not demonstrate disease progression were randomized to immediate docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 d for six cycles or were given docetaxel with the same dosage and schedule once they presented with disease progression[12]. Immediate administration of docetaxel maintenance therapy demonstrated a statistically significant increase in median PFS compared with delayed docetaxel (5.7 mo vs 2.7 mo, P = 0.001). Median OS was not statistically significant for either arm of the study and no molecular testing on patients’ tumors was completed.

The “PointBreak” study randomized advanced NSCLC patients to pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, carboplatin AUC = 6, B 15 mg/kg induction every 21 d with four cycles, with maintenance pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, B 15 mg/kg [pemetrexed and bevacizumab (PB)] vs paclitaxel 200 mg/m2, carboplatin AUC = 6, B 15 mg/kg induction every 21 d for four cycles, with maintenance B 15 mg/kg[17,18]. The maintenance therapy for both arms was given until disease progression. Median PFS was significantly higher for PB vs B at 6 mo vs 5.6 mo, respectively (P = 0.012, HR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.7-0.96). Median OS was not significantly different for PB vs B at 12.6 mo vs 13.4 mo, respectively. The primary endpoint of improved median OS was not met. While tumor molecular testing was conducted, the types of testing and results have not been reported.

The FLEX study, randomized previously untreated advanced NSCLC patients to cisplatin 80 mg/m2 plus vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 every 3 wk for six cycles, with or without cetuximab 400 mg/m2 day 1 and 250 mg/m2 day 8 and all subsequent doses weekly[19]. Cetuximab maintenance was given until disease progression/toxicities. Median PFS was not statistically significant (P = 0.39, HR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.82-1.07). Median OS for cetuximab vs observation was 11.3 mo vs 10.1 mo (P = 0.044, HR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.76-0.99). Tumor molecular testing was conducted for EGFR immunohistochemistry and was part of the entry criteria for study eligibility.

The AVAIL study, randomized advanced NSCLC patients to cisplatin 80 mg/m2 plus gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 every three weeks for six cycles, with either B (7.5 mg/kg), B (15 mg/kg), or placebo every three weeks until disease progression[20]. Median PFS for low dose B vs placebo was 6.7 mo vs 6.1 mo (P = 0.003, HR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.62-0.91). Median PFS for high dose B vs placebo was 6.5 mo vs 6.1 mo (P = 0.03, HR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.68-0.98). Median OS was not analyzed due to insufficient follow-up duration at the time of data reporting. Overall, B as maintenance therapy does improve PFS. No tumor molecular testing was conducted.

The SATURN study evaluated erlotinib as maintenance therapy in advanced NSCLC patients who received one of seven different platinum based doublet chemotherapy regimens (type of regimens were not specified)[3]. Induction therapy was given for four cycles followed by erlotinib 150 mg/d vs placebo until disease progression, toxicity, or death. No B or pemetrexed were used in the induction chemotherapy regimens. Median PFS for erlotinib vs placebo was significantly prolonged at 4.1 mo vs 2.75 mo, respectively (P < 0.0001, HR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.58-0.82). Median OS with erlotinib vs placebo was also significantly improved at 12 mo vs 11 mo (P = 0.0088, HR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.70-0.95). From this trial, molecular testing of EGFR immunohistochemistry was reported.

The BMS-099 study, randomized advanced NSCLC patients to carboplatin AUC = 6 plus either docetaxel 75 mg/m2 or paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 every three weeks for six cycles or carboplatin AUC = 6 plus either docetaxel 75 mg/m2 or paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 every three weeks for six cycles with cetuximab 400 mg/m2 day 1, 250 mg/m2 day 8 and each subsequent dose[21]. Cetuximab was given weekly until disease progression/toxicities. Median PFS and OS were not statistically significant. Maintenance cetuximab added no clinical benefit to PFS or OS. No tumor molecular testing was included in this study.

The PARAMOUNT study evaluated the use of pemetrexed as continuation maintenance therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC nonsquamous histology[22,23]. Patients were given pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 every three weeks for four cycles. Patients were then randomized to pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 continuation maintenance every three weeks until disease progression or placebo. Median PFS was significantly higher for pemetrexed maintenance vs placebo at 4.1 mo vs 2.8 mo, respectively (P < 0.0001, HR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.49-0.79). Median OS was significantly higher for pemetrexed maintenance vs placebo at 13.9 mo vs 11 mo, respectively (P = 0.0195, HR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.64-0.96). The use of pemetrexed as continuation maintenance therapy can significantly increase median PFS and OS in patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC. No tumor molecular testing was conducted.

The IFCT-GFPC 0502 study evaluated gemcitabine (continuation maintenance) vs erlotinib (switch maintenance) vs observation as maintenance therapy after induction therapy with cisplatin 80 mg/m2 and gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 every three weeks for four cycles in patients with advanced NSCLC[11]. Patients were then randomized to gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 every three weeks, erlotinib 150 mg/d every three weeks, or observation until disease progression, toxicity, or death. Median PFS for gemcitabine vs erlotinib vs observation was 3.8 mo (P < 0.001, HR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.44-0.72) vs 2.9 mo (P = 0.003, HR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.54-0.88) vs 1.9 mo. Median OS was not significantly different for gemcitabine vs erlotinib vs observation at 12.1 mo vs 11.4 mo vs 10.8 mo; respectively. Molecular testing was completed for EGFR immunohistochemistry (IHC) (n = 261) and EGFR mutation (n = 188). Fourteen different EGFR mutations were noted [exon 19 deletion (n = 10), exon 21 (n = 4)]. EGFR IHC had no significant effect on median PFS for gemcitabine or erlotinib therapy and there were too few cases of EGFR mutations for analysis.

The AVAPREL study evaluated the use of B with or without pemetrexed as maintenance therapy in advanced NSCLC with nonsquamous histology with B 7.5 mg/kg, cisplatin 75 mg/m2 and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 every three weeks for four cycles as induction chemotherapy regimen[24]. Patients were randomized to B 7.5 mg/kg alone or B 7.5 mg/kg plus pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 (PB) given every three weeks until disease progression/toxicities. Median PFS for PB vs B was 7.4 mo vs 3.7 mo (P < 0.001, HR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.35-0.66). Median OS was not significantly different between the two arms. No tumor molecular testing was completed in this study.

Therapy for advanced NSCLC should be individualized based upon the molecular features of the tumor. Whenever possible, tumor tissue should be assessed for the presence of a somatic driver abnormality (e.g., mutated EGFR, ALK rearrangement) which confers sensitivity to a specific inhibitor[25]. Unfortunately, many clinical trials do not require collection of tumor tissue for molecular analysis as either entry criteria or for subsequent analysis. There are no randomized trials conducted in patients known to have an EGFR mutation or other driver abnormality prior to the initiation of maintenance chemotherapy. After review of maintenance therapy trials cited here, three of ten had molecular subtypes identified and two of these three trials had pre-planned analysis for molecular subtype EGFR mutations. Furthermore, structuring of clinical trials that identify patients with molecular alterations and evaluating their response to standard maintenance therapy has been minimal[26]. An improved understanding of the molecular pathways that drive malignancy in NSCLC has led to the development of agents that target specific molecular pathways in malignant cells. These agents have been a significant step forward in the treatment of patients whose tumors contain specific mutations in these pathways. Most patients with advanced NSCLC whose tumors contain a driver mutation are initially treated with the appropriate targeted agent (e.g., erlotinib, gefitinib, or crizotinib). For patients with advanced NSCLC who were initially treated with chemotherapy but in whom a driver mutation has subsequently been identified, continuation of therapy with an appropriate targeted agent after the initial cycles of chemotherapy are complete is recommended[3].

By taking into consideration patient demographics and obtaining molecular testing target treatment plans can be made. EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements are more common in NSCLC tumors of patients that have a history of never to light smoking, compared to Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations which are often found in tumors of heavy smokers[27]. Treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (such as erlotinib, gefitinib, or afatinib) as single agents is indicated for the initial management of patients whose tumors contain an activating mutation in EGFR. In this setting, first-line treatment with an EGFR TKI improves PFS compared to standard platinum-based chemotherapy. The impact on OS is less clear, since EGFR TKIs were frequently used as second line therapy after chemotherapy in the clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of this approach. EGFR TKIs generally are not combined with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy as initial therapy, since these combinations have not prolonged survival even when patients were selected for sensitivity to these EGFR TKIs based upon clinical criteria. In the absence of significant toxicity, treatment with an EGFR TKI is continued until there is evidence of progression. An example of second-line therapy that has been shown to be more effective in a specific patient population is pemetrexed and ALK rearranged tumors. ALK-positive tumors have a significant response to pemetrexed leading to longer PFS when compared to KRAS mutant, EGFR mutant, or triple negative tumors in patients treated with pemetrexed[27]. Information on molecular subtypes should be considered[26]. Pemetrexed is cost effective for patients with non-squamous cell histology and shows the importance in identifying patients who will benefit from pemetrexed maintenance therapy[8].

Crizotinib, an inhibitor of the ALK tyrosine kinase, is preferred as first-line therapy in patients whose tumor contains the ALK fusion oncogene. Phase II studies using crizotinib demonstrated an objective response rate over 50 percent in previously treated patients with ALK rearrangements, with a median duration of response greater than 40 wk in responders. A phase III trial demonstrated a significant increase in PFS compared to standard chemotherapy in patients who had previously received one platinum-containing regimen[28]. Further development and research can help distinguish if ALK-positive tumors are responsive to cytotoxic agents or specifically responsive to pemetrexed alone. Such findings can improve the way NSCLC patients with distinct tumor molecular phenotypes are treated and how these treatments can impact outcomes[27].

The role of maintenance treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC is under active investigation. There are several factors to consider when choosing to start a patient on maintenance therapy. These factors include deciding how and whether to continue therapy including patient’s tolerance for these agents, absence or presence of molecular mutations, patient specific factors like co-morbidities, toxicity associated with the original treatment, and desire to balance clinical benefit vs toxicity of immediate further treatment. The studies reviewed have shown that maintenance therapy could provide clinical benefit in specific advanced NSCLC patients. However, as alluded to earlier, few features that can help identify those most likely to benefit from maintenance therapy have been identified.

Not all advanced NSCLC lung cancer patients are made equal and continuation maintenance therapy to date may improve OS in first-line therapy responders[11], whereas switch maintenance therapy, can improve OS in patients with stable disease after first-line therapy[29]. More research into identifying factors that contribute to response rate of various maintenance therapies would allow for better selection of patients to receive maintenance therapy[26]. A recent study identified patients who normally were not qualifying candidates based on common clinical trial inclusion guidelines (such as socioeconomically disadvantaged and patients with greater symptom burden requiring pre-chemotherapy palliative radiation therapy), and observed that this subset of patients maintained stable disease after first line chemotherapy without additional therapy and at time of disease progression responded well to second-line chemotherapy. This is an example of how some patients may benefit successfully without the use of maintenance therapy[30]. Identification of these factors will assist providers to better define patient populations who should receive maintenance chemotherapy and decrease costs and toxicities in patients who may or may not benefit from having maintenance chemotherapy.

Measurement of PFS and OS should not be the only factors determining the success of maintenance therapy. Patient perspectives need to be taken into consideration. PFS is valued if disease symptoms are minimal, but these gains can be offset as disease symptoms progress or toxicity burden from treatment impacts that patient[30]. Clinical benefit is an important determinant in deciding if patients are candidates for maintenance therapy. By identifying patients’ goals and their tolerance of adverse symptoms, determination about the appropriate use of maintenance therapy can be made.

An additional factor when determining the utilization of maintenance therapy is cost effectiveness of maintenance therapy, which can vary depending on location. For example, maintenance pemetrexed is more cost effective compared to other maintenance therapies in the United Kingdom, but is not cost effective in the United States[30]. Identification of those patients who will gain the greatest benefit from maintenance therapy will help balance efficacy, cost, and patient preferences.

Several of the studies displayed statistically significant results for primary or secondary endpoint PFS. Although PFS was prolonged in many studies, the concern of “statistical significance” in relation to clinical significance needs attention by the critical eye of a clinician. A result that is statistically significant does not mean that the result is clinically significant and vice versa[31]. Historically and currently, the trend for reporting and interpreting clinical trial results are not based on the prospect of clinical importance[32]. When interpreting clinical trial results, the P value is not the only “value” indicating that the study was statistically significant. The number of subjects in the study contributes largely to reaching a statistically significant number, but not a clinically significant result[31]. For example, a study with a very large number of subjects commonly will show significant P values but overall, the clinical significance and treatment differences are very small[31].

There have been four maintenance studies to date reporting statistically significant improved PFS and OS. Three out of the four studies, ECOG4599, JMEN, and PARAMOUNT, did not report tumor molecular analysis. The former study involved B maintenance and the latter two studies involved pemetrexed maintenance. The fourth study, SATURN, did evaluate patient tumors for EGFR mutation retrospectively, however, those with EGFR mutations had the most dramatic “benefit” of significantly prolonged PFS and OS[3]. Unfortunately, the majority of maintenance studies reviewed did not conduct molecular testing. To accurately measure the clinical benefit of maintenance therapy in advanced NSCLC patients, their molecular tumor analysis or prospective sample collection should be included as criteria for future clinical trials. As discussed above, the question of clinical vs statistical significance is important to point out with all four of these studies. All were very large study populations (at least 663 subjects each) and while the primary results demonstrated statistically significant improvements in median OS, the reality is these are not blockbuster changes for clinically meaningful improvement over standard platinum based doublet therapy in exchange for potential increased treatment-related toxicity and financial-related toxicity.

Other considerations to take into account for maintenance therapy as more oral biologic agents come to the clinic, is patient adherence with their prescribed anticancer therapy. Adherence to treatment is a major factor that can impact outcomes, though the quality of data on this topic and interventions to improve adherence need improvement as well[33].

Precision-based oncology care allows treatment of advanced NSCLC to be personalized to the patient not the cancer. Just as TKIs have been incorporated into standard of care for treatment of patients with specific tumor molecular mutations[4], TKIs and metabolic inhibitors have and may continue to demonstrate more significant prolongation of PFS and OS in patients with molecular mutations. As oncologists and advanced practitioners create treatment plans for advanced NSCLC patients, testing for molecular mutations is crucial for selecting the right treatment and stratifying how best to treat patients eligible for systemic therapy. A suggested algorithm for treating stage 4 NSCLC is outlined in Figure 1. By taking histology and molecular subtypes into consideration, more succinct and clear identification of patients that would benefit from one maintenance therapy agent vs other alternatives is likely important. Molecular subtypes may behave differently to various standard therapies resulting in the need for developing of targeted therapies for patients with NSCLC[27]. More advancement is needed in treating NSCLC patients that do not display molecular mutations[9]. By recognizing these new developments as well as limitations, there is a need for clinicians to be able to identify patients who will have the greatest benefit and effectiveness from maintenance therapy.

P- Reviewers: Korpanty G, Hida T, Zhang YJ S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | World Health Organization. Cancer. 2013, cited 2013-10-30. Available from: http: //www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. |

| 2. | Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, Tzekova V, Ramlau R, Ghilezan N, Ciuleanu T, Cucevic B, Gyurkovits K, Ulsperger E. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:155-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Szczésna A, Juhász E, Esteban E, Molinier O, Brugger W, Melezínek I. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 856] [Cited by in RCA: 905] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2013, cited 2013-10-30. Available from: http: //www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. |

| 5. | Gridelli C, Ciardiello F, Gallo C, Feld R, Butts C, Gebbia V, Maione P, Morgillo F, Genestreti G, Favaretto A. First-line erlotinib followed by second-line cisplatin-gemcitabine chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TORCH randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3002-3011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lima JP, dos Santos LV, Sasse EC, Sasse AD. Optimal duration of first-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:601-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Soon YY, Stockler MR, Askie LM, Boyer MJ. Duration of chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3277-3283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Klein R, Wielage R, Muehlenbein C, Liepa AM, Babineaux S, Lawson A, Schwartzberg L. Cost-effectiveness of pemetrexed as first-line maintenance therapy for advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1263-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gerber DE, Schiller JH. Maintenance chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: new life for an old idea. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1009-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, Kim JH, Krzakowski M, Laack E, Wu YL, Bover I, Begbie S, Tzekova V. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2009;374:1432-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 843] [Cited by in RCA: 840] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pérol M, Chouaid C, Pérol D, Barlési F, Gervais R, Westeel V, Crequit J, Léna H, Vergnenègre A, Zalcman G. Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3516-3524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fidias PM, Dakhil SR, Lyss AP, Loesch DM, Waterhouse DM, Bromund JL, Chen R, Hristova-Kazmierski M, Treat J, Obasaju CK. Phase III study of immediate compared with delayed docetaxel after front-line therapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:591-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, Gatzemeier U, Digumarti R, Zukin M. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543-3551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2484] [Cited by in RCA: 2489] [Article Influence: 146.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Syrigos KN, Vansteenkiste J, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Manegold C, Martins RG, Simms L, Sugarman KP, Visseren-Grul C, Scagliotti GV. Prognostic and predictive factors in a randomized phase III trial comparing cisplatin-pemetrexed versus cisplatin-gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:556-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Westeel V, Quoix E, Moro-Sibilot D, Mercier M, Breton JL, Debieuvre D, Richard P, Haller MA, Milleron B, Herman D. Randomized study of maintenance vinorelbine in responders with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:499-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542-2550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4457] [Cited by in RCA: 4447] [Article Influence: 234.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Patel JD, Bonomi P, Socinski MA, Govindan R, Hong S, Obasaju C, Pennella EJ, Girvan AC, Guba SC. Treatment rationale and study design for the pointbreak study: a randomized, open-label phase III study of pemetrexed/carboplatin/bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed/bevacizumab versus paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patel JD, Socinski MA, Garon EB, Reynolds CH, Spigel DR, Olsen MR, Hermann RC, Jotte RM, Beck T, Richards DA. PointBreak: a randomized phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4349-4357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, von Pawel J, Krzakowski M, Ramlau R, Vynnychenko I, Park K, Yu CT, Ganul V. Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1031] [Cited by in RCA: 1042] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, Leighl N, Mezger J, Archer V, Moore N. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1227-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1098] [Cited by in RCA: 1139] [Article Influence: 71.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, McCleod M, Heim WJ, Hermann RC, Paschold E, Iannotti NO, Dakhil S, Gorton S. Cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the randomized multicenter phase III trial BMS099. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:911-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Paz-Ares L, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, Molinier O, Sahoo TP, Laack E, Reck M. Maintenance therapy with pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care after induction therapy with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (PARAMOUNT): a double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Paz-Ares LG, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, Molinier O, Sahoo TP, Laack E, Reck M. PARAMOUNT: Final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2895-2902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Barlesi F, Scherpereel A, Rittmeyer A, Pazzola A, Ferrer Tur N, Kim JH, Ahn MJ, Aerts JG, Gorbunova V, Vikström A. Randomized phase III trial of maintenance bevacizumab with or without pemetrexed after first-line induction with bevacizumab, cisplatin, and pemetrexed in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAPERL (MO22089). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3004-3011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, Jenkins RB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Saldivar JS, Squire J. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:823-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 634] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Dearing KR, Weiss GJ. Molecular characterization may be of PARAMOUNT importance. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:481-482. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Camidge DR, Kono SA, Lu X, Okuyama S, Barón AE, Oton AB, Davies AM, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin W, Doebele RC. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangements in non-small cell lung cancer are associated with prolonged progression-free survival on pemetrexed. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:774-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn MJ, De Pas T, Besse B, Solomon BJ, Blackhall F. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385-2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2534] [Cited by in RCA: 2691] [Article Influence: 224.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Coudert B, Ciuleanu T, Park K, Wu YL, Giaccone G, Brugger W, Gopalakrishna P, Cappuzzo F. Survival benefit with erlotinib maintenance therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) according to response to first-line chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:388-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gerber DE, Rasco DW, Le P, Yan J, Dowell JE, Xie Y. Predictors and impact of second-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the United States: real-world considerations for maintenance therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Furburg B, Furburg C. Evaluating clinical research, all that glitters is not gold. 2nd ed. New York: Springer 2007; 107-108. |

| 32. | Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Rourke K, Molnar FJ, Mahon J, Chan KB, Wells G. Determination of the clinical importance of study results. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bassan F, Peter F, Houbre B, Brennstuhl MJ, Costantini M, Speyer E, Tarquinio C. Adherence to oral antineoplastic agents by cancer patients: definition and literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:22-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |