Published online May 10, 2013. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v4.i2.52

Revised: March 29, 2013

Accepted: April 9, 2013

Published online: May 10, 2013

Processing time: 88 Days and 5.2 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the outcomes and potential prognostic factors in patients with non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS).

METHODS: Patients with histologically proven non-AIDS-related KS treated with systemic chemotherapy were included in this retrospective analysis. In some cases, the human herpes virus 8 status was assessed by immunohistochemistry. The patients were staged according to the Mediterranean KS staging system. A multivariable model was constructed using a forward stepwise selection procedure. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were two-sided.

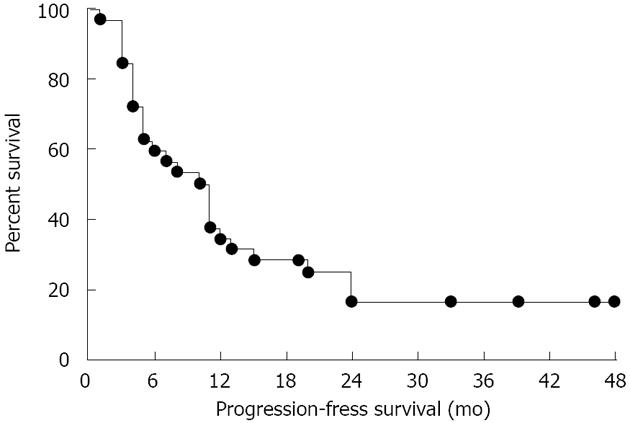

RESULTS: Thirty-two cases were included in this analysis. The average age at diagnosis was 70 years, with a male/female ratio of approximately 2:1. Eighty-four percent of the cases had classic KS. All patients received systemic chemotherapy containing one of the following agents: vinca alkaloid, taxane, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Ten patients (31.5%) experienced a partial response, and a complete response was achieved in four patients (12.4%) and stable disease in sixteen cases (50%). Two patients (6.2%) were refractory to the systemic treatment. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 11.7 mo, whereas the median overall survival was 28.5 mo. At multivariate analysis, the presence of nodular lesions (vs macular lesions only) was significantly related to a lower PFS (hazard ratio: 3.09; 95%CI: 1.18-8.13, P = 0.0133).

CONCLUSION: Non-AIDS-related KS appears mostly limited to the skin and is well-responsive to systemic therapies. Our data show that nodular lesions may be associated with a shorter PFS in patients receiving chemotherapy.

Core tip: Non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is usually relatively benign, with an indolent disease course. It appears to be highly responsive to a wide variety of chemotherapy agents, including pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, vinca-alkaloids, etoposide and taxanes. However, factors predictive of progression-free survival are lacking. In our series of 32 patients with non-AIDS-related KS, we showed that presence of nodular lesions (vs macular lesions only) was associated with a 3-fold increased risk of progression. If confirmed by further studies, such a finding may be useful to improve the therapeutic strategy for this disease at the individual level.

- Citation: Rescigno P, Trolio RD, Buonerba C, Fata GD, Federico P, Bosso D, Virtuoso A, Izzo M, Policastro T, Vaccaro L, Cimmino G, Perri F, Matano E, Delfino M, Placido SD, Palmieri G, Lorenzo GD. Non-AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: A single-institution experience. World J Clin Oncol 2013; 4(2): 52-57

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v4/i2/52.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v4.i2.52

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a multifocal angioproliferative disorder of the vascular endothelium that usually presents itself with multiple vascular, cutaneous and mucosal nodules[1].

The four described clinical variants, i.e., classic, endemic, iatrogenic and epidemic KS, show a distinct natural history and prognosis[2], but all share a causal relationship with human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8)[3]. Infection with this virus is a necessary condition, but it is not sufficient alone to cause KS, highlighting how genetic and angiogenic factors and the production of several inflammatory cytokines play a role in the multistep pathogenesis of KS[4].

As KS can be considered to be an opportunistic tumour, the restoration of immune competence is associated with remission in organ transplant recipients[5] and in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related KS[6]. In classic KS, the cause of the underlying immunodeficiency is more difficult to identify and therefore to target by treatment.

Classic KS is a rare and mild form of the disease, primarily affecting men over 50 years old in endemic areas[7]. Lesions present themselves as purplish-red pigmented nodules on the legs and arms and tend to spread to more proximal sites[8]. The reported male-to-female ratio is 17:1[9]. Patients with classic KS have a greater risk to develop solid or haematopoietic neoplasms[10].

Iatrogenic KS is associated with the use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents[11]. The duration of immunosuppressive therapy does not seem to affect the risk of KS[12]. Iatrogenic KS more frequently involves the lymph nodes and viscera compared with classic KS[1,2].

The definition of the therapeutic strategy for KS depends on a number of factors, which include the location and variant of the KS, the pace of disease progression, the presence and severity of the symptoms (e.g., pain and oedema), the number of lesions, the degree of host immune competence and comorbidities[2,7,13].

We present data about the treatment, response and outcome of 32 patients with non-AIDS-related KS treated with chemotherapy at our institution from January 2008 to December 2012.

A retrospective review study of patients who received systemic treatment for classic or iatrogenic KS from January 2008 to December 2012 at the Division of Dermatology and Oncology of University Hospital Federico II, Naples was performed. Informed consent for the anonymous publication of the data was obtained for all patients.

Patients who had histologically proven KS lesions of the skin and were negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1/2 by macro enzyme immunoassay were included in this study. The histologic diagnosis required the presence of proliferative miniature vessels and tumour-like fascicles composed of spindle cells and a vascular network[1,2]. The HHV-8 status was assessed by immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal antibody against the latent nuclear antigen 1. Positivity for HHV-8 confirmed but was not strictly necessary for the diagnosis.

The tumour staging was performed with an ultrasound of the abdomen and the superficial lymph nodes, a chest X-ray and/or a whole body computed tomography scan. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy and rectosygmoidoscopy were performed in fit patients. Demographic features, such as origin, age at onset and gender, of the patients were retrieved. Data regarding the type, response and duration of the first systemic treatment delivered at our Institution and its related progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), comorbidities, number and extent of lesions and the presence of complications, such as lymphoedema, haemorrhage, pain, functional impairment and ulcerations, were also extracted from a review of the charts. The staging was performed according to criteria by Brambilla et al[14].

Five levels of the response to treatment were defined according to the revised World Health Organization criteria[15]: complete response, major response, minor response, stable disease and progression. All levels were based on the number of lesions: complete response, 100% resolution of the lesions; major response, > 50% to < 100% decrease; minor response, > 25% to < 50% decrease; stable disease, < 25% decrease to < 25% increase; and progression, > 25% increase in the number of lesions or worsening of the tumour-associated pain/oedema. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to investigate the prognostic factors of PFS and OS. A multivariable model was constructed using a forward stepwise selection procedure. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were two-sided. All results are considered hypothesis-generating and require independent validation.

Thirty-two cases of non-AIDS-related KS were included in this study. The mean age at diagnosis was 70 years. Twenty-one patients (65.6%) were male, and 11 (34.4%) were female, with an approximate male:female ratio of 2:1. All patients were Italian. With respect to the clinical subtype, 27 (84.3%) cases of classic KS and five cases (15.6%) of iatrogenic KS were included in this analysis. Of note, two patients with classic KS suffered from tumour-induced immunosuppression: one had B-cell lymphoma, and the other presented with Good’s syndrome associated with a thymic epithelial tumour[16].

In particular, three patients were on immunosuppressive therapy due to an autoimmune disease (rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus). The medication used included systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporin A. Two patients were on systemic corticosteroids due to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All 25 cases tested for HHV-8 were positive.

In 90.6% (n = 29) of the cases, the KS was limited to the skin. One patient (3.1%) presented mucosal lesions of the glans, and another case had axillary lymph node invasion. The KS lesions were multiple (> 3) in all patients (n = 32). The patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| Patients number | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 21 (65.6) |

| Female | 11 (34.4) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 6 (18.7) |

| Alzheimer’s | 2 (6.3) |

| Hypertension | 15 (46.9) |

| Kaposi variant | |

| Classic | 27 (84.3) |

| Iatrogenic | 5 (15.6) |

| Anatomic site | |

| Limbs | 24 (75) |

| Limbs and trunk | 5 (15.6) |

| Scrotum | 1 (3.1 ) |

| Glans | 1 (3.1 ) |

| Lymph node involvement | 1 (3.1) |

| Number of lesions | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 |

| > 3 | 32 (100) |

| Stage | |

| Stage IIb | 18 (56.2) |

| Stage III-IV | 14 (43.7) |

All patients received systemic chemotherapy. The most frequently used drugs were vinblastine, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) and paclitaxel. One patient (3.1%) affected by thymoma and KS received gemcitabine, capecitabine and immunoglobulins. The treatments that were administered are detailed in Table 2.

| Patients number | |

| Sytemic treatment1 | |

| Vinblastine | 17 (53.1) |

| Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin | 8 (25) |

| Paclitaxel | 5 (15.6) |

| Gemcitabine | 1 (3.1) |

| Vinorelbine | 1 (3.1) |

| Overall number of lines of systemic treatment received by the patient | |

| 1 line | 26 (81.2) |

| > 1 line | 6 (18.8) |

We obtained a disease control rate (93.8%), as shown in Table 3. The median PFS was 11.7 mo (range, 3-48 mo) (Figure 1), and the median OS was 28.5 mo (range, 12-48 mo) (Table 3).

| Response | |

| Complete response | 4 (12.4) |

| Partial response | 10 (31.5) |

| Stable disease | 16 (50) |

| Progressive disease | 2 (6.2) |

| Progression-free survival, mo (range) | 11.7 (3-48) |

| Overall survival, mo (range) | 28.5 (12-48) |

Of note, the presence of nodular lesions was related to a lower PFS compared with macular lesions in both the univariate and multivariate analyses. The results of the Cox proportional hazard analysis are detailed in Table 4.

| Characteristic | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Univariable | ||

| Stage (II vs III/IV) | 1.63 (0.74-3.57) | 0.22 |

| Cutaneous lesion (macules vs nodules) | 3.09 (1.18-8.13) | 0.01 |

| Extent (lower limb only vs other parts of the body) | 1.61 (0.72-3.59) | 0.24 |

| Symptoms (no vs yes) | 0.72 (0.32-1.62) | 0.44 |

| Age | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.16 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 0.73 (0.32-1.69) | 0.47 |

| Multivariable | ||

| Cutaneous lesion (nodular/papular/macules vs macules only) | 3.09 (1.18-8.13) | 0.013 |

No death was directly related to KS. One patient, affected by Good’s syndrome, died as a result of an opportunistic infection.

Classic KS is a rare disease. Its incidence is affected by factors such as sex, age and immune status. Interestingly, the geographic origin may affect the female to male ratio, as shown by the male to female ratio reported in our case series (2:1) and in a case series of 874 classic KS patients from 15 Italian Cancer Registries (3:2)[17], which appear to be markedly different from that reported in other studies conducted in distinct geographic areas[9,10].

Different routes of transmission have been hypothesised for HHV-8[17]. In addition to sexual transmission, a number of studies support a role for saliva as an infection route. The copy numbers of HHV-8 were higher in the saliva then in the semen in patients with and without KS, and these differences were independent of the HIV status. Oropharyngeal epithelial cells may harbour HHV-8 and facilitate its replication[18]. A potential role in HHV-8 transmission could be played by haematophagous insects (e.g., malaria vector Anopheles, black flies, sand flies, biting midges and mosquitoes), which could explain the high incidence in Italian areas where wetlands and swamps are widespread (e.g., the Po delta and part of Sardinia) and malaria is epidemic[17]. Notably, the majority of our patients are elderly people from Campania, an area that used to be covered by wetlands.

Classic and iatrogenic KS mostly present themselves as multiple bilateral cutaneous lesions of the lower limbs[10]. We found that the lesions were multiple in 100% of the cases, as expected in a series of patients undergoing systemic treatment, and that the lesions involved the limbs in 75% of the cases. Only one patient with lymph-nodal disease was identified in our series.

One finding of interest was that the patients with nodular lesions appeared to display a more aggressive course of the disease, with an increased risk of progression compared with the patients with macular lesions in the multivariate analysis (hazard ratio: 3.09; 95%CI: 1.18-8.13; P = 0.0133). These data have not been reported previously in the literature.

A number of cytotoxic agents proved to be effective for the systemic treatment of recurrent, visceral, aggressive and widespread disease. These agents have not been tested in large, randomised-controlled trials[19]. The response rates (> 50% decrease in lesions) associated with the chemotherapy agents in classic KS ranged between 71% and 100% for PLD[20-22], 58% and 90% for vinca-alkaloids[23-25], 74% and 76% for etoposide[26], and 93% and 100% for taxanes[27,28]. Gemcitabine showed a response in 100% of the patients[29], and the combination of vinblastine and bleomycin was associated with a response rate of 97%[30].

All of these agents were employed in our patient population (PLD, vinca alkaloids, taxanes, and gemcitabine), with a remarkable overall disease control rate of 93.7%, which is in line with the literature data. At the time of the analysis, no patient had died as a direct consequence of KS, which confirmed the relatively benign behaviour of classic KS[31].

We performed immunohistochemical tests for HHV-8 staining on tissue samples of 25 patients (78.1%). All 25 patients (100%) were positive for infection.

These data suggest the high sensitivity of immunohistochemistry to detect HHV-8 infection, as previously reported in the literature[32].

In summary, in this study, KS nodular lesions appeared to be significantly associated with a decreased PFS in patients receiving chemotherapy. In sharp contrast to AIDS-related KS, classic and iatrogenic KS appear to have a more indolent course, being mostly limited to the skin and highly responsive to systemic therapeutic strategies.

The retrospective nature of this study and the small sample size mandate confirmation of our findings in further prospective trials.

We thanks American Journal Experts for editing service.

Non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) usually displays an indolent course, with a relatively benign behaviour of the disease. It is generally highly responsive to chemotherapy agents, including pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, vinca-alkaloids, etoposide and taxanes. However, some patients show a more aggressive course of the disease.

Factors predictive of progression-free survival associated with chemotherapy are lacking and are required in this rare disease.

The multivariate analysis performed in our series of 32 patients with non-AIDS-related KS showed that the presence of nodular lesions (vs macular lesions only) is associated with a 3-fold increased risk of progression.

If confirmed by further studies, the presence of nodular lesions may be incorporated into the clinical decision-making process for the definition of the therapeutic strategy for this disease on an individual level.

Juman herpes virus 8 stands for human herpes virus 8, a large double-stranded DNA virus that is the causative agent of KS.

The paper by Rescigno et al evaluates outcomes and potential prognostic factors in patients with classic and iatrogenic KS. In this study the authors retrospectively reviewed all cases of non-AIDS related KS treated at their institution from January 2008 to December 2012. One finding of interest was that patients with nodular lesions appeared to display a more aggressive course of the disease, with an increased risk of progression compared to patients with macular lesions at multivariate analysis (HR: 3.09; 95%CI: 1.18-8.13; P = 0.0133). These data were not reported before in literature. The paper is well written and of interest for readers.

P- Reviewers Mohanna S, Okuma Y S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fatahzadeh M. Kaposi sarcoma: review and medical management update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:2-16. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mancuso R, Biffi R, Valli M, Bellinvia M, Tourlaki A, Ferrucci S, Brambilla L, Delbue S, Ferrante P, Tinelli C. HHV8 a subtype is associated with rapidly evolving classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Med Virol. 2008;80:2153-2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ensoli B, Sgadari C, Barillari G, Sirianni MC, Stürzl M, Monini P. Biology of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1251-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stallone G, Schena A, Infante B, Di Paolo S, Loverre A, Maggio G, Ranieri E, Gesualdo L, Schena FP, Grandaliano G. Sirolimus for Kaposi’s sarcoma in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1317-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 742] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martinez V, Caumes E, Gambotti L, Ittah H, Morini JP, Deleuze J, Gorin I, Katlama C, Bricaire F, Dupin N. Remission from Kaposi’s sarcoma on HAART is associated with suppression of HIV replication and is independent of protease inhibitor therapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1000-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jakob L, Metzler G, Chen KM, Garbe C. Non-AIDS associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Naschitz JE, Lurie M. Macular palmo-plantar eruption. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:e118-e119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang J, Stebbing J, Bower M. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma and gender. Gend Med. 2007;4:266-273. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cohen CD, Horster S, Sander CA, Bogner JR. Kaposi’s sarcoma associated with tumour necrosis factor alpha neutralising therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Louthrenoo W, Kasitanon N, Mahanuphab P, Bhoopat L, Thongprasert S. Kaposi’s sarcoma in rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;32:326-333. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, Scuderi L. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brambilla L, Boneschi V, Taglioni M, Ferrucci S. Staging of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma: a useful tool for therapeutic choices. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:83-86. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12751] [Cited by in RCA: 13073] [Article Influence: 522.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vitiello L, Masci AM, Montella L, Perna F, Angelini DF, Borsellino G, Battistini L, Merola G, De Palma R, Spadaro G. Thymoma-associated immunodeficiency: a syndrome characterized by severe alterations in NK, T and B-cells and progressive increase in naïve CD8+ T Cells. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23:307-316. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Dal Maso L, Polesel J, Ascoli V, Zambon P, Budroni M, Ferretti S, Tumino R, Tagliabue G, Patriarca S, Federico M. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Italy, 1985-1998. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:188-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Casper C, Krantz E, Selke S, Kuntz SR, Wang J, Huang ML, Pauk JS, Corey L, Wald A. Frequent and asymptomatic oropharyngeal shedding of human herpesvirus 8 among immunocompetent men. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Régnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kreuter A, Rasokat H, Klouche M, Esser S, Bader A, Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Brockmeyer NH. Liposomal pegylated doxorubicin versus low-dose recombinant interferon Alfa-2a in the treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma; retrospective analysis of three German centers. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:653-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Di Lorenzo G, Kreuter A, Di Trolio R, Guarini A, Romano C, Montesarchio V, Brockmeyer NH, De Placido S, Bower M, Dezube BJ. Activity and safety of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as first-line therapy in the treatment of non-visceral classic Kaposi’s sarcoma: a multicenter study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1578-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, Palmieri G, Nappa P, Delfino M, De Placido S, Dezube BJ. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brambilla L, Labianca R, Boneschi V, Fossati S, Dallavalle G, Finzi AF, Luporini G. Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma in the elderly. A randomized study of oral etoposide versus vinblastine. Cancer. 1994;74:2873-2878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brambilla L, Labianca R, Fossati S, Boneschi V, Ferrucci S, Clerici M. Vinorelbine: an active drug in Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1995;5:467-469. |

| 25. | Zidan J, Robenstein W, Abzah A, Taman S. Treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma with vinblastine in patients with disseminated dermal disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:251-253. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Brambilla L, Boneschi V, Fossati S, Melotti E, Clerici M. Oral etoposide for Kaposi’s Mediterranean sarcoma. Dermatologica. 1988;177:365-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Brambilla L, Romanelli A, Bellinvia M, Ferrucci S, Vinci M, Boneschi V, Miedico A, Tedeschi L. Weekly paclitaxel for advanced aggressive classic Kaposi sarcoma: experience in 17 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1339-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fardet L, Stoebner P-E, Bachelez H, Descamps V, Kerob D, Meunier L. Treatment with taxanes of refractory or life-threatening Kaposi sarcoma not associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Cancer. 2006;106:1785-1789. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Brambilla L, Labianca R, Ferrucci SM, Taglioni M, Boneschi V. Treatment of classical Kaposi’s sarcoma with gemcitabine. Dermatology. 2001;202:119-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, Romanelli A, Brambati M, Vinci M, Tedeschi L, Boneschi V. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Di Lorenzo G. Update on classic Kaposi sarcoma therapy: new look at an old disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Courville P, Simon F, Le Pessot F, Tallet Y, Debab Y, Métayer J. [Detection of HHV8 latent nuclear antigen by immunohistochemistry. A new tool for differentiating Kaposi’s sarcoma from its mimics]. Ann Pathol. 2002;22:267-276. [PubMed] |