Published online Oct 10, 2011. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v2.i10.344

Revised: September 20, 2011

Accepted: September 24, 2011

Published online: October 10, 2011

Primary mucosal melanoma of the paranasal sinuses is a rare tumor of the head and neck which can be a devastating disease. Cancers arising in the sinonasal cavity are extremely rare, with a poor survival rate. There is inherent difficulty in diagnosing these lesions due to their complex anatomic locations and symptoms which are often confused with more common benign processes. The primary treatment of this rare disease process is resection, except in advanced stages where surgical resection is not an option. Diagnostic accuracy in consideration of size, location, and presence of metastatic disease of these malignant tumors tailors individual patients to different management in order to achieve the longest possible survival.

- Citation: Gasparyan A, Amiri F, Safdieh J, Reid V, Cirincione E, Shah D. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the paranasal sinuses: Two case presentations. World J Clin Oncol 2011; 2(10): 344-347

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v2/i10/344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v2.i10.344

Malignant mucosal melanoma of the sinuses is a rare, devastating disease of the head and neck. Cancers arising in the sinonasal cavity have an incidence of approximately 1 in 500 000 to 1 in 1 000 000 people in the general population[1]. The lesions typically present at an advanced stage with a 5-year survival rate between 5% and 30%. There is inherent difficulty in diagnosing these lesions due to their complex anatomic locations and symptoms which are often confused with more common benign processes. The mainstay of treatment is resection with negative margins. We present 2 cases of malignant mucosal melanoma, which presented to our institution 14 years apart. In the first patient, the disease originated in the left maxillary sinus and masqueraded as chronic epistaxis and conjunctivitis. The second patient presented with epistaxis only, as his disease manifested earlier originating in the right frontal sinus. Based on their disease presentation and stage, each patient was managed differently.

A 60-year-old female presented to our institution after experiencing several months of left eye pain and vision disturbances. Her symptoms began 6 mo prior and became progressively worse. The patient also complained of headaches followed by rare episodes of epistaxis. She had been to outside facilities including an ophthalmologist prior to her admission to our hospital. She had been diagnosed with conjunctivitis and sent home with appropriate antibiotic ophthalmic ointments. She had no other significant medical or surgical history and was otherwise a healthy 60-year-old female.

Physical examination revealed a tender protruding left eyeball with marked visual loss and tearing. The right eye was unremarkable. Left extraocular muscles showed minimal function. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head, orbits, and sinuses revealed a large destructive invasive mass involving primarily the left maxillary sinus and left ethmoidal air cells with intracranial and intraorbital extension (Figures 1 and 2). Ear nose and throat surgeons were consulted who performed an intranasal excisional biopsy of the growth. Using immunohistochemisty, the pathologists reported the biopsied specimen as malignant melanoma. Neurosurgeons stated that no surgical intervention was possible at the present time due to the invasive extent of the tumor into the brain parenchyma. The patient and her family were informed of her terminal condition. The patient’s intermittent episodes of epistaxis were controlled by nasal packing. Adequate pain medications were prescribed. She was discharged to a hospice facility with palliative support after a 1-mo stay at our institution.

A 62-year-old male presented to our facility with a 3-mo history of right-sided intermittent epistaxis. The patient stated that he had required 4 hospitalizations in the past 3 mo due to his severe nosebleeds and on one occasion required a blood transfusion. He also complained of right-sided facial pressure and breathing difficulties through his right nostril. He denied visual disturbances and headaches. Much like our first patient, he had no past medical or surgical history.

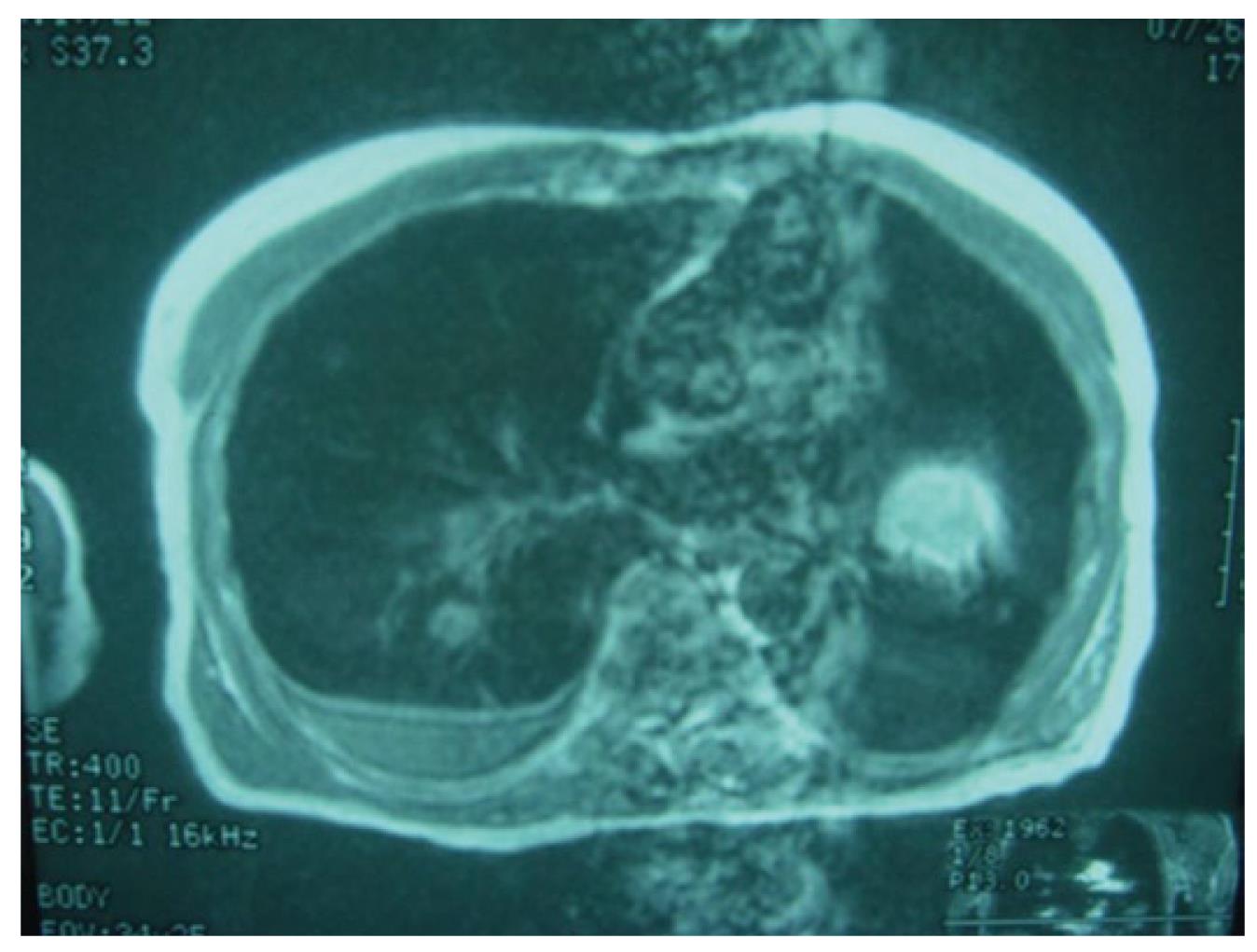

On physical examination, a friable fungating mass with moderate bleeding was identified in the right nasal cavity. CT scan demonstrated a large enhancing soft tissue mass centered in the right ostiomeatal complex extending into the right maxillary sinus, right ethmoid air cells and right nasal cavity (Figure 3). Following excisional biopsy, the pathologists identified the lesion as malignant mucosal melanoma. The patient was promptly scheduled for surgery. He underwent right enucleation, right maxillectomy and hemipalatectomy, with removal of the nasal septum, excision of the right superior, middle and inferior turbinates and right ethmoidectomy (Figure 4). He received postoperative radiation therapy. At 4-mo follow-up, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) identified abnormal soft tissue within the posterior aspect of the surgical cavity. The oncologists at our institution closely followed the patient until he presented to the emergency room with shortness of breath and dry cough 4 years post-operatively. Chest X-ray revealed a nodule and CT of the chest demonstrated bilateral lung masses with calcifications and at least two discrete nodules suspicious for metastatic disease (Figure 5). The patient underwent a left thoracotomy with resection of nodules and blebs. The pathology report stated metastatic melanoma. The patient expired 6 years after the primary diagnosis of paranasal sinus melanoma.

Malignant mucosal melanoma is an uncommon disease, which can be devastating to the patient. At the time of presentation, the lesions are at an advanced stage which lowers the survival rate of patients. Approximately 60%-70% of malignancies of the nasal cavity including the sinuses occur in the maxillary sinus with 10%-15% in the ethmoid air cells and the remainder in the sphenoid and frontal sinuses. The most common malignant neoplasm of the paranasal sinus is squamous cell carcinoma occurring in 70%-80% of all cases. In contrast, the incidence of malignant melanoma of the head and neck and nasal cavities varies from 0.4%-4%[2]. Even though age and sex do not affect the prognosis of the disease, men are affected 1.5 times more than women and 80% of these tumors occur in people aged 45-85 years old[3,4].

Sino nasal malignancies are difficult to treat and have a poor prognosis. The neoplasms growing within the body confined to the paranasal sinuses are often asymptomatic until they erode or invade adjacent structures. Hence, one reason for the poor prognosis is the close proximity to vital structures such as the skull base, brain, orbits, and carotid artery[5]. Tumors invading through the roof of the maxillary sinus can invade the eye and ultimately impact its function as was the case with both our patients. In addition, maxillary sinus tumors which invade the posterior wall gain access to nerves and vessels at the base of the skull and pterygomaxillary space and eventually have the opportunity to directly invade the brain[1]. Unfortunately, our first patient had brain invasion making her disease unresectable (Figures 1 and 2). Typical symptoms upon presentation include nasal discharge, obstruction, epistaxis, and pressure sensation in the midface. Late presentations may include proptosis, diplopia, blurred vision, tearing and in very advanced disease, loss of vision.

Diagnostic evaluation includes a thorough physical examination of the head and neck including assessment of overall facial asymmetry, extraocular muscle evaluation, pupillary response, and signs of globe displacement. Intranasal exam may include flexible or rigid endoscopy for visualization of the nasal cavity[5]. Imaging studies are usually obtained prior to biopsy.

Both CT and MRI may be utilized to further characterize sinonasal malignancies. According to an article published by the American Head and Neck Society, MRI is thought to be more accurate as it provides better definition of tumor margins in relation to surrounding structures. Ultimately biopsy is the only accurate mean of obtaining tissue diagnosis. A fundamental principle is to obtain representative tissue by the least invasive method possible[2]. Although immunohistochemical stains are usually not necessary for diagnosis, they are generally performed for completeness, as in both of our patients. The pathology report indicated that both S100 and homatropine methylbromide (HMB45) status were positive for melanoma (Figure 6). S100 is highly sensitive, but not specific, for identifying melanoma, whereas HMB45 is highly specific and moderately sensitive. For cases in which staining of these two markers yields unclear results, a melanoma specific marker known as melan A is typically used, which is shown to be highly specific in differentiating melanoma from other malignancies[1].

The National Cancer Institute classifies malignant mucosal melanomas based on anatomic primary areas into cancer of the maxillary sinus and cancer of the nasal cavity/ethmoid sinuses. However, there is no universally accepted provision for paranasal sinus melanoma staging within the TNM system according to Cheng and Lai’s 2007 article “Towards a Better Understanding of Sino Nasal Mucosal Melanoma”[6]. Most clinicians use a simplified three-stage system: stage I for localized disease, stage II for lymph node metastases, and stage III for distant metastasis [1]. Our second patient had lung metastasis making him stage III, even after surgical management and postoperative radiation therapy (Figures 4 and 5).

Treatment of malignant melanoma of the paranasal sinuses is carried out on a case-by-case basis and depends on the extent and location of the tumor. While complete resection of the mucosal melanoma is generally the goal in the absence of distant metastases, it should be noted that more than half of patients in whom local control is achieved after surgery ultimately develop distant metastases. Surgical excision is challenging because of the proximity of critical structures such as the eyes and brain, which make excision and high dose radiotherapy extremely difficult[7]. Thus, it is difficult to secure histological disease-free margins in the affected anatomic sites. Often, complicated procedures require the involvement of multiple surgical specialties such as ear, nose and throat surgeons, neurosurgeons, and maxillofacial surgeons. Even though traditionally these tumors were known to be radioresistant, some investigations suggest the use of radiation therapy after resection of mucosal melanoma[1]. Therefore, complete surgical removal of tumor and postoperative radiation therapy is the standard of care for resectable lesions[5,6]. Clinical data has proven that combining chemotherapy (either intra-arterial or intravenous) along with radiation therapy may improve local control of paranasal sinus tumors. Post-treatment follow-up must be frequent and continuous as malignant melanoma of paranasal sinuses carries a high rate of local recurrence and metastasis, as was the case with our second case presentation. Thus, these patients require lifetime follow-up including yearly chest X-rays to exclude metastatic disease to lungs[8]. If the disease is more severe, as in the case of unresectable lesions, which include those with brain involvement, carotid artery incasement, and bilateral optic nerve involvement, palliative care is the treatment of choice[7,9].

In conclusion, malignant melanoma of the sinuses is a rare and complicated disease, which presents with nasal obstruction, epistaxis, sinusitis, and exophthalmus. The diagnostic tools to identify the type and extent of tumor invasion include a thorough physical examination, CT scan, MRI, and biopsy, and even then diagnosis remains exceedingly difficult. Unfortunately, the prognosis of mucosal paranasal melanoma remains poor with a mean 5-year overall survival rate of only 15.7%[6,10]. The key and critical issue in dealing with malignant mucosal melanoma of paranasal sinuses is early diagnosis in order to comply with the primary modality of treatment, which is surgical excision and radiation therapy with adequate follow-up.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Paul J Higgins, Department of Center for Cell Biology and Cancer Research, Albany Medical College, 47 New Scotland Avenue, Albany, New York, NY 12208, United States

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Patel SG, Prasad ML, Escrig M, Singh B, Shaha AR, Kraus DH, Boyle JO, Huvos AG, Busam K, Shah JP. Primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2002;24:247-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Berthelsen A, Andersen AP, Jensen TS, Hansen HS. Melanomas of the mucosa in the oral cavity and the upper respiratory passages. Cancer. 1984;54:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Batsakis JG, Regezi JA, Solomon AR, Rice DH. The pathology of head and neck tumors: mucosal melanomas, part 13. Head Neck Surg. 1982;4:404-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Snow GB, van der Waal I. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1986;19:537-547. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Popović D, Milisavljević D. Malignant tumors of the maxillary sinus: A ten year experience. Med Biol. 2004;11:31-34. |

| 6. | Cheng YF, Lai CC, Ho CY, Shu CH, Lin CZ. Toward a better understanding of sinonasal mucosal melanoma: clinical review of 23 cases. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Towensend C. Sabiston textbook of Surgery. 17th ed. In: Townsend C, Beachamp D, Mattox K. Towensend Textbook of Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences 2004; 833-867. |

| 8. | Seliger B, Ritz U, Abele R, Bock M, Tampé R, Sutter G, Drexler I, Huber C, Ferrone S. Immune escape of melanoma: first evidence of structural alterations in two distinct components of the MHC class I antigen processing pathway. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8647-8650. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Grewal DS, Lele SY, Mallya SV, Baser B, Bahal NK, Rege JD. Malignant melanoma of nasopharynx extending to the nose with metastasis in the neck. J Postgrad Med. 1994;40:31-33. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wong JH, Cagle LA, Storm FK, Morton DL. Natural history of surgically treated mucosal melanoma. Am J Surg. 1987;154:54-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |