Published online Apr 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i4.104827

Revised: February 17, 2025

Accepted: March 4, 2025

Published online: April 24, 2025

Processing time: 78 Days and 5.5 Hours

Chronic neuropathic pain and depression are common and debilitating conditions in cancer patients, significantly impacting their quality of life. Pregabalin, an anticonvulsant medication, is used for neuropathic pain and may also influence depressive symptoms. This study evaluates the efficacy and safety of pregabalin on pain intensity, depression severity, and side effects in cancer patients with chronic neuropathic pain and depression.

To evaluate the impact of pregabalin on pain intensity, depression severity, and the safety profile in cancer patients with chronic neuropathic pain and depression.

This observational case series included 10 cancer patients experiencing chronic neuropathic pain and depression. Pregabalin was administered at a starting dose of 150 mg twice daily, with adjustments based on patient tolerance and pain response up to 300 mg twice daily. Pain intensity and depression severity were assessed using the brief pain inventory (BPI) and the Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks. Side effects were monitored using a self-reported side effect questionnaire.

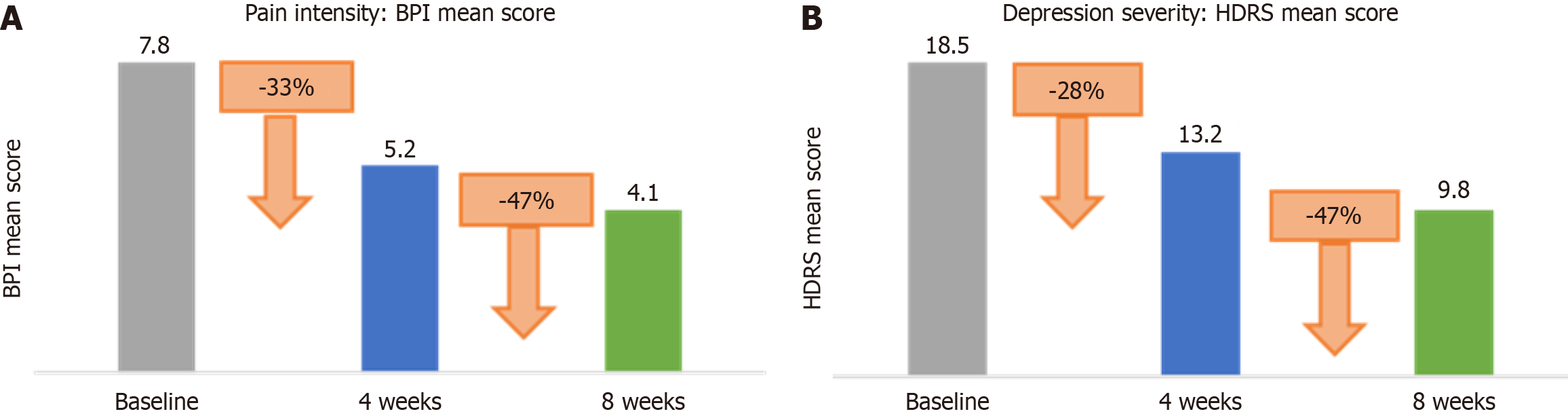

Pregabalin led to a significant reduction in pain intensity and depression severity. The mean BPI score decreased from 7.8 (SD = 1.2) at baseline to 5.2 (SD = 1.4) at 4 weeks and 4.1 (SD = 1.5) at 8 weeks, representing reductions of 33.3% and 47.4%, respectively. The mean HDRS score decreased from 18.5 (SD = 4.0) at baseline to 13.2 (SD = 4.1) at 4 weeks and 9.8 (SD = 3.6) at 8 weeks, showing reductions of 28.4% and 47.0%, respectively. Side effects included dizziness (50%), drowsiness (40%), weight gain (30%), and dry mouth (20%). No severe adverse effects were reported. All patients completed the study, with 30% requiring dose adjustments.

Pregabalin significantly alleviates both chronic neuropathic pain and depression in cancer patients with a manageable safety profile. These findings support the use of pregabalin in this patient population, though further research with larger samples and controlled designs is warranted.

Core Tip: The study found that pregabalin significantly reduced both pain intensity and depression severity in terminal cancer patients. Pain levels, as measured by the brief pain inventory, saw a 47.4% reduction, while depressive symptoms, assessed using the Hamilton depression rating scale, experienced a similar reduction of 47.0%. Side effects were manageable, with no severe adverse effects reported. These findings indicate that pregabalin holds promise as a treatment option to improve the quality of life in terminal cancer patients, though further research is needed to substantiate these results.

- Citation: Chakraborty P, Borgohain M. Evaluating pregabalin in cancer patients with chronic neuropathic pain and depression: an observational case series. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(4): 104827

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i4/104827.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i4.104827

Chronic neuropathic pain and depression are prevalent comorbidities in cancer patients, both of which contribute profoundly to the deterioration of their physical and emotional well-being. Neuropathic pain, often arising from cancerous infiltration of nerve tissue or chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity, can be excruciating and resistant to conventional analgesics. Concurrently, depression is frequently exacerbated by the burdens of a diagnosis, physical debilitation, and the overwhelming psychological distress associated with end-of-life issues. The interplay between these two conditions is bidirectional; pain exacerbates depression, and depression, in turn, amplifies the perception of pain, thus perpetuating a vicious cycle that severely compromises the patient’s overall quality of life.

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying this interaction are complex, involving alterations in central pain processing, heightened sensitivity to nociceptive stimuli, and dysregulation of mood-affective pathways[1]. The co-occurrence of these symptoms often leads to a multifaceted clinical scenario where both the emotional and somatic facets of the patient’s suffering must be addressed concurrently. As a result, integrated pain management strategies that also target mood disturbances are crucial in improving the overall well-being of these patients.

Pregabalin, a gabapentinoid anticonvulsant agent primarily utilized in the management of neuropathic pain, has demonstrated promising efficacy in reducing the intensity of such pain, particularly in conditions like diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia. Mechanistically, pregabalin binds to the α2δ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels in the central nervous system, thereby inhibiting excitatory neurotransmitter release and modulating pain pathways. Interestingly, emerging evidence suggests that pregabalin may also exert antidepressant-like effects, likely via its modulatory action on the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems, which are implicated in both mood regulation and nociception[2].

Despite the potential dual benefits of pregabalin in mitigating both neuropathic pain and depressive symptoms, its application in cancer patients has been relatively underexplored. This patient population presents unique challenges, including altered pharmacokinetics due to compromised organ function, polypharmacy, and the advanced nature of their disease. Moreover, concerns surrounding the safety profile of pregabalin, particularly its sedative effects and potential for cognitive impairment, must be carefully weighed against its therapeutic benefits[1-3]. The paucity of rigorous clinical trials specifically targeting cancer patients underscores the need for more focused research to determine whether pregabalin can be a safe and effective therapeutic option for managing the dual burden of chronic neuropathic pain and depression in this vulnerable group.

In conclusion, while pregabalin shows promise as a multifaceted agent for improving both pain and mood in neuropathic conditions, its role in the management of cancer patients remains inadequately studied. Given the profound impact of neuropathic pain and depression on the quality of life in this cohort, further clinical investigation is warranted to better define its efficacy and safety profile, with a view toward optimizing symptom management and enhancing the end-of-life experience for these individuals.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of pregabalin on pain intensity, depression severity, and the safety profile in cancer patients with chronic neuropathic pain and depression.

This study was an observational case series conducted over an 8-week period. The study was granted ethical clearance by the institutional review board of Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, as documented in the approval number EC-2022-012-6, on November 2, 2022.

All paramedic staff, including nurses and blood technicians, undergo thorough training to recruit cancer patients and monitor side effects during treatment. The training covers understanding eligibility criteria, the informed consent process, and how to clearly communicate study details, risks, and benefits to patients. Nurses are also trained to detect and document side effects early, with clear protocols for reporting adverse reactions and adjusting care. This collaborative approach ensures patient safety and timely management of side effects, supporting accurate data collection throughout the study. Participants of this observational study were recruited through outpatient departments of Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, Oncology. Potential participants were identified by the principal investigator based on their medical history and current health status. Recruitment took place over a 24-week period, from January 10 to June 26, 2023. Patients who met the study’s inclusion criteria were approached for participation.

Eligible patients were screened based on their medical records to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. A brief interview with the principal investigator was conducted to confirm understanding of the study and to clarify any questions. During the screening phase, each patient underwent a basic health assessment, which included measurement of blood pressure, a review of their current medications, and an overall physical examination. The exclusion criteria were strictly applied at this stage. Patients with recent changes in their medical condition, new diagnoses, or those with conditions that could interfere with the study (e.g., current opioid usage) were excluded. If a patient did not meet the inclusion criteria or met any of the exclusion criteria, they were informed and not invited to participate.

Once a patient was deemed eligible, they were provided with a detailed informed consent form explaining the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study in local language. Participants were given sufficient time to read the consent form and ask any questions. Informed consent was obtained in person, and each participant signed the form before any study-related activities were carried out.

Participants were scheduled for follow-up visits at 4 weeks and 8 weeks during the observational period to monitor their health and ensure continued participation. Reminder calls and text messages were sent to reduce drop-out rates.

(1) Diagnosis of terminal cancer: Patients must have a confirmed diagnosis of terminal cancer, including lung, breast, prostate, or pancreatic cancer; (2) Presence of chronic neuropathic pain: Patients should experience chronic neuropathic pain as a primary symptom and validated using Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) questionnaire; (3) Comorbid depression: Participants must also have a clinically significant diagnosis of depression, as evaluated by the Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS); (4) Treatment eligibility: Patients who have not been using opioid analgesics for pain control. Diclofenac for severe pain was allowed for a period of up to 7 days as and when required; and (5) Ability to provide consent: Patients capable of providing informed consent or through a legal representative.

(1) Opioid use: Patients currently using opioid analgesics for pain management; (2) Severe psychiatric illness: Excluding patients with psychiatric conditions that could interfere with study assessments, beyond depression; (3) Uncontrolled medical conditions: Excluding patients with other significant uncontrolled medical conditions that could interfere with the study, such as severe cardiac or renal issues; (4) Pregnancy: Female patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding; and (5) Allergy or contraindication to pregabalin: Exclusion of patients with a known hypersensitivity to pregabalin.

The study included 10 terminal cancer patients (6 females and 4 males) with a mean age of 65 years (range: 50-80 years). The types of cancer included lung cancer (4 patients), breast cancer (3 patients), prostate cancer (2 patients), and pancreatic cancer (1 patient). The diagnosis of neuropathic pain in each patient was meticulously established using the validated DN4 questionnaire[4], alongside a thorough physical examination and detailed patient history. A DN4 score of ≥ 4 was considered diagnostic for neuropathic pain, providing a robust criterion for classification. Additionally, computed tomography scans were performed to gain insights into the underlying pathophysiology, specifically to assess tumor-related nerve compression or infiltration, which could be contributing to the neuropathic pain in these patients. This comprehensive diagnostic approach ensures a precise and evidence-based determination of neuropathic pain in the context of cancer. Tables 1 and 2 summarizes the demographic information for the terminal cancer patients involved in the study.

| Characteristic | Details | Concomitant medications |

| Total number of patients | 10 | |

| Gender | 6 females, 4 males | |

| Mean age | 65 years | |

| Age range | 50-80 years | |

| Cancer types | Lung cancer: 4 patients (40%) | Cisplatin; Paclitaxel; Ondansetron; Dexamethasone; Diclofenac |

| Breast cancer: 3 patients (30%) | Doxorubicin; Cyclophosphamide; Zolendronic acid; Letrozole;Anastrozole; Dexamethasone; Diclofenac | |

| Prostate cancer: 2 patients (20%) | Leuprolide; Enzalutamide; Zolendronic acid; Diclofenac | |

| Pancreatic cancer: 1 patient (10%) | Gemcitabine; 5-Fluorouracil; Dexamethasone; Diclofenac |

| Sl. No. | Gender | Age | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Baseline investigations |

| 1 | Female | 67 | 172 | 58 | LFT: WNL; KFT: WNL |

| 2 | Female | 64 | 170 | 50 | NA |

| 3 | Female | 62 | 168 | 49 | LFT: WNL; KFT: WNL |

| 4 | Female | 66 | 165 | 52 | NA |

| 5 | Female | 61 | 171 | 60 | LFT: WNL; KFT: WNL |

| 6 | Female | 65 | 169 | 55 | LFT: WNL; KFT: WNL |

| 7 | Male | 80 | 175 | 60 | NA |

| 8 | Male | 66 | 173 | 64 | NA |

| 9 | Male | 69 | 172 | 57 | LFT: WNL; KFT: WNL |

| 10 | Male | 71 | 180 | 68 | NA |

(1) Medication: Pregabalin; (2) Starting dose: 150 mg twice daily; (3) Dose adjustment: Doses were adjusted up to a maximum of 300 mg twice daily based on patient tolerance and pain response. The dosing protocol for pregabalin begins with a starting dose of 300 mg per day, divided into two tablets of 150 mg daily. The dose can be increased gradually, based on patient tolerance and pain response, up to a maximum of 300 mg twice daily (600 mg per day). This titration ensures that the medication is tailored to each patient’s needs, balancing efficacy with safety; and (4) 300 mg twice daily pregabalin dose escalation: The escalation to 300 mg of pregabalin twice daily after one week is driven by the clinical need for prompt and effective pain relief in patients who have not experienced significant improvement with diclofenac alone. While diclofenac 100 mg/day was administered to all patients experiencing severe pain after study enrolment, it has limited efficacy in treating neuropathic pain. Given the absence of prior opioid use and the need for enhanced pain management, the decision to increase the pregabalin dose aims to achieve more rapid pain control. There was no predefined pain threshold; however, patients who received diclofenac were asked to attend follow-up visits (n = 3). The decision to escalate the dose was made by the principal investigator based on the patient's response to treatment.

The selection of assessment tools for this study was made with careful consideration of their established reliability, validity, and sensitivity in capturing the key variables of interest-pain intensity, depression severity, and side effects-within the context of the research. Each tool was chosen not only for its scientific rigor but also for its applicability to the specific aims of the study, ensuring the most accurate and meaningful measurement of the outcomes.

Pain intensity-brief pain inventory: The brief pain inventory (BPI) was selected as the primary instrument for measuring pain intensity due to its widespread use and proven ability to accurately assess both the intensity and the interference of pain on daily functioning. The BPI allows for the quantification of pain severity across a range of conditions, making it highly relevant for clinical research, particularly in studies assessing the efficacy of treatments for pain management. Its validated scales provide reliable insights into patients' subjective pain experiences, while the tool’s brevity ensures that it can be administered efficiently without burdening participants. Furthermore, the BPI’s versatility in both acute and chronic pain assessments aligns well with the objectives of this study[5].

Depression severity-HDRS: The HDRS was chosen to assess depression severity due to its status as one of the most widely utilized and extensively validated tools for evaluating the depth of depressive symptoms in both clinical and research settings. As a clinician-administered scale, the HDRS provides a comprehensive evaluation of depression through a multidimensional approach, covering affective, cognitive, and somatic symptoms. Its sensitivity to changes in symptom severity over time, as well as its ability to detect subtle variations in depressive states, makes it an ideal choice for assessing the impact of therapeutic interventions, such as pregabalin, on depression-related symptoms. The HDRS has been rigorously tested across various populations, ensuring its applicability and robustness in the context of this study[6,7].

Side effects-self-reported side effect questionnaire: To monitor side effects associated with treatment, a self-reported side effect questionnaire was utilized. This approach was chosen for its practicality and ease of administration, allowing participants to directly report any adverse effects they experienced during the study. The self-report format provides an efficient means of capturing a broad range of side effects, particularly those that are subjective and difficult to measure through clinical observation alone. Additionally, using a self-reported measure ensures that the data reflects the participants' personal experiences, offering a more comprehensive view of the treatment’s safety profile. While self-reports are inherently prone to bias, the questionnaire was carefully designed to minimize these concerns through clear and neutral phrasing, and participants were encouraged to provide detailed responses to improve the accuracy of the data collected.

Together, these tools were chosen to provide a balanced, multi-faceted approach to evaluating the effects of pregabalin on pain, depression, and side effects. Each instrument is grounded in established psychometric principles, offering both depth and precision in measuring the key outcomes of the study. By utilizing these tools, the study aimed to capture not only the clinical efficacy of the treatment but also the participants' lived experiences in a comprehensive and scientifically rigorous manner.

Baseline assessment: The baseline assessment was conducted prior to the commencement of pregabalin administration, serving as the critical reference point for subsequent evaluations. During this phase, participants were thoroughly assessed to establish a comprehensive understanding of their initial clinical status, including baseline pain intensity, depression severity, and any pre-existing side effects. This data provided an essential foundation for comparing subsequent changes and gauging the efficacy of the intervention over time.

4-week assessment: The intermediate assessment, conducted at the four-week mark, provided a mid-point evaluation of the participants' response to the treatment regimen. At this stage, the effects of pregabalin were expected to begin manifesting, allowing for a preliminary analysis of changes in pain intensity, depressive symptoms, and the emergence of side effects. This evaluation facilitated the identification of any early trends or noteworthy alterations in the participants’ condition, thus informing the ongoing course of treatment and offering a pivotal insight into the therapeutic trajectory.

8-week assessment: The final assessment, performed at the conclusion of the eight-week period, represented the culmination of the study's evaluative timeline. This comprehensive assessment encapsulated the cumulative effects of pregabalin on the study's primary outcomes-pain, depression, and side effects-by comparing the final data with both baseline and intermediate measurements. The eight-week mark allowed for a thorough investigation of the long-term impact of the treatment, providing conclusive insights into its efficacy, safety profile, and overall benefit. This assessment was critical in determining the enduring effects of pregabalin and facilitating the interpretation of its clinical significance within the context of the study.

The statistical analysis was meticulously executed to evaluate the relationships between the variables and to ensure the robustness of the study’s findings. The primary tools employed for measurement were the BPI to assess pain intensity, the HDRS to gauge the severity of depressive symptoms, and a self-reported side effect questionnaire to monitor adverse effects associated with the treatment.

For each of the three time points-baseline (prior to the initiation of pregabalin), 4 weeks (intermediate assessment), and 8 weeks (final assessment)-the data were subjected to rigorous statistical procedures. The distribution of pain intensity scores, depression severity, and side effect frequency were evaluated at each time point to assess intra-individual changes and inter-group variations, if applicable.

This study represents a pioneering investigation involving 10 terminally ill cancer patients who also have comorbid depression and neuropathic pain. To enhance the comparability between participants and reduce the impact of con

Additionally, effect sizes were calculated to quantify the magnitude of the observed changes in pain intensity, depression severity, and side effects, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of the treatment's impact. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 28), and results were interpreted with respect to their clinical significance in addition to their statistical relevance.

At baseline, patients reported moderate pain and depression severity. Over the course of the study, both pain and depression scores showed significant improvements. After 4 weeks, pain and depression levels had notably decreased, and these reductions were further sustained at 8 weeks. The occurrence of side effects was generally mild, with dizziness, drowsiness, weight gain, and dry mouth being the most frequently reported. However, none of the patients experienced any severe adverse effects. Additionally, while a small portion of patients required an increase in their medication dose, the majority did not need any adjustments, and all patients successfully completed the study.

The mean BPI score at baseline was 7.8 (SD = 1.2). After 4 weeks, the mean score decreased to 5.2 (SD = 1.4), representing a 33.3% reduction. By 8 weeks, the mean score further decreased to 4.1 (SD = 1.5), a 47.4% reduction from baseline (Table 3).

| Time point | BPI mean score | Standard deviation | Reduction from baseline | Percentage reduction (%) |

| Baseline | 7.8 | 1.2 | - | - |

| 4 weeks | 5.2 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 33.3 |

| 8 weeks | 4.1 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 47.4 |

The mean HDRS score at baseline was 18.5 (SD = 4.0). At 4 weeks, the score decreased to 13.2 (SD = 4.1), a 28.4% reduction. By 8 weeks, the mean HDRS score was 9.8 (SD = 3.6), reflecting a 47.0% reduction (Table 4).

| Time point | HDRS mean score | Standard deviation | Reduction from baseline | Percentage reduction (%) |

| Baseline | 18.5 | 4.0 | - | - |

| 4 weeks | 13.2 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 28.4 |

| 8 weeks | 9.8 | 3.6 | 8.7 | 47.0 |

The most common side effects were dizziness (50%), drowsiness (40%), weight gain (30%), and dry mouth (20%). No severe adverse effects were reported (Table 5).

| Side effect | Number of patients | Percentage of total patients (%) |

| Dizziness | 5 | 50 |

| Drowsiness | 4 | 40 |

| Weight gain | 3 | 30 |

| Dry mouth | 2 | 20 |

Three patients (30%) required an increase to 300 mg twice daily, while the remaining seven patients (70%) did not require any dose adjustments. All patients completed the study (Tables 6 and 7).

| Dose adjustment | Number of patients | Percentage of total patients (%) |

| Increased to 300 mg twice daily | 3 | 30 |

| No change | 7 | 70 |

| Adherence rate | Number of patients | Percentage of total patients (%) |

| Completed study period | 10 | 100 |

Our study found that pregabalin significantly reduced both pain intensity and depression severity in terminal cancer patients over an 8-week period (Figure 1). These findings are consistent with the pharmacological profile of pregabalin, which targets the α2-δ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, thereby inhibiting excitatory neurotransmitter release and providing analgesic effects[3]. The dual reduction in pain and depression scores suggests that pregabalin may not only alleviate neuropathic pain but also contribute to the improvement of depressive symptoms, possibly due to its anxiolytic properties. This dual benefit is particularly important in the context of terminal cancer care, where the interplay between chronic pain and depression can severely impact patients' quality of life. The significant reduction in HDRS scores observed in our study aligns with findings from Kroenke et al[8], who demonstrated that effective pain mana

The safety profile of pregabalin observed in our study was favorable, with common side effects such as dizziness and drowsiness being manageable and not leading to discontinuation. These findings are consistent with previous literature, including the systematic review by Derry et al[2], which reported that while pregabalin is generally well-tolerated, some patients may experience side effects that require dose adjustment. Our study's 30% rate of dose adjustment reflects the necessity of individualized treatment plans to optimize therapeutic outcomes while minimizing adverse effects.

In our study, 50% of patients reported dizziness, but regular telephonic assessments by nurses helped mitigate fall risks, and no patient required a dose reduction of pregabalin. 40% of patients experienced mild drowsiness, yet they remained able to communicate, eat, and engage in daily activities, so no dose adjustments were needed. 30% gained weight, but this did not worsen health conditions like edema or impaired breathing, and for patients with poor appetite, weight gain was linked to improved appetite rather than fluid retention, with careful monitoring in place. 20% of patients had dry mouth, for which hydration and oral hygiene were emphasized. Throughout the study, individualized management strategies ensured that treatment contributed positively to patients' overall well-being.

The absence of severe adverse effects in our cohort further corroborates the safety of pregabalin in this patient population. However, the small sample size limits the generalizability of these findings, and larger studies are needed to confirm the safety profile of pregabalin in terminal cancer patients, particularly over longer treatment periods.

Our findings contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting the use of pregabalin for neuropathic pain mana

Moreover, the study by Freynhagen et al[9] emphasized the importance of identifying neuropathic components in pain syndromes, which is particularly relevant in the cancer population where mixed pain syndromes are common. Our use of the BPI allowed for the effective assessment of pain intensity, and the substantial reductions in BPI scores observed in our study suggest that pregabalin effectively addresses the neuropathic components of cancer-related pain.

The clinical implications of our findings are significant, as they suggest that pregabalin may be a valuable addition to the palliative care regimen for terminal cancer patients, providing relief from both chronic neuropathic pain and associated depressive symptoms. Given the multidimensional impact of pain and depression on the quality of life, incorporating pregabalin into treatment protocols could lead to more holistic care for these patients.

However, the limitations of our study, including its small sample size, lack of a control group, and the subjective nature of pain and depression assessments, must be addressed in future research. Larger, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to validate these findings and explore the long-term efficacy and safety of pregabalin in this patient population. Additionally, studies that investigate the mechanistic links between pain relief and mood improvement with pregabalin treatment could provide further insights into its therapeutic potential.

Neuropathic cancer pain with depression is a complex and relatively rare condition, presenting significant challenges in recruiting a sufficient number of participants, particularly those who have not previously been treated with opioid analgesics. Furthermore, the severity of cancer-related pain and associated depression raises important ethical considerations, which have constrained the ability to recruit a large sample. This is especially pertinent given that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the use of pregabalin specifically in this patient population. As such, the study involves interventions that may carry potential risks of harm or discomfort, necessitating a careful approach with a smaller sample size to minimize burden on these vulnerable individuals.

The small sample size (n = 10) in the current observational study significantly limits the generalizability and statistical power of the results. A sample size of 10 participants may not fully capture the diversity of the population being studied, which introduces a risk of bias and reduces the ability to make broad conclusions. This limitation can affect the external validity (generalizability) of the findings, making it difficult to apply the results to larger, more diverse groups or to inform clinical practice reliably.

From a statistical perspective, the small sample size reduces the study's power to detect significant differences or relationships. The power of a study refers to the likelihood of detecting an effect if one truly exists. With a small sample, there is a higher chance of type II errors (failing to detect a true effect) and greater sensitivity to outliers or individual variations that might not be representative of the larger population. Consequently, the findings from this study may be either overstated or understated, depending on the nature of the sample.

Furthermore, an observational design, while valuable for exploratory research, is subject to confounding factors that may influence the results. Larger, controlled studies allow for better control over potential confounders and provide a more accurate estimate of the relationships being investigated. RCTs or larger cohort studies, which minimize bias and confounding, would be better suited to confirm the findings and improve the robustness of the conclusions.

Therefore, while this study provides important preliminary insights, it is essential to conduct future research with larger sample sizes to improve the statistical power and generalizability of the results. Larger, controlled studies are needed to better understand the phenomena under investigation and to provide reliable evidence that can inform clinical practice with greater confidence.

While the small sample size of 10 participants may limit the generalizability of the findings and reduce statistical power, this study has nevertheless provided valuable insights. As a pilot or exploratory investigation, its findings lay a crucial foundation for future, larger-scale studies designed to validate and expand upon these initial observations.

In conclusion, our study provides preliminary evidence that pregabalin is effective in reducing both pain and depression in terminal cancer patients, with a manageable safety profile. These findings align with existing literature on pregabalin's efficacy in neuropathic pain and its potential benefits in alleviating depressive symptoms. While promising, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the study's limitations, and further research is warranted to confirm and expand upon these findings.

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to all individuals and institutions whose contributions were instrumental in the successful completion of this study. We extend our heartfelt thanks to the Institutional Review Board of Gauhati Medical College and Hospital for their ethical oversight and approval, ensuring that the study was conducted in strict adherence to the highest standards of scientific integrity and participant welfare. We are grateful to the participants who generously volunteered their time and effort, without whom this study would not have been possible. Their cooperation and commitment to the research process were vital in the collection of valuable data and the advancement of scientific knowledge. Lastly, we acknowledge the invaluable support of the administrative and technical staff at Gauhati Medical College and Hospital for their assistance in facilitating the smooth conduct of the study. Their behind-the-scenes efforts in ensuring the timely execution of assessments and maintaining the study’s logistical framework were in

| 1. | Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Backonja M, Farrar JT, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Kalso EA, Loeser JD, Miaskowski C, Nurmikko TJ, Portenoy RK, Rice ASC, Stacey BR, Treede RD, Turk DC, Wallace MS. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1450] [Cited by in RCA: 1356] [Article Influence: 75.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Derry S, Bell RF, Straube S, Wiffen PJ, Aldington D, Moore RA. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD007076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Taylor CP, Angelotti T, Fauman E. Pharmacology and mechanism of action of pregabalin: the calcium channel alpha2-delta (alpha2-delta) subunit as a target for antiepileptic drug discovery. Epilepsy Res. 2007;73:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aho T, Mustonen L, Kalso E, Harno H. Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) stratifies possible and definite neuropathic pain after surgical peripheral nerve lesion. Eur J Pain. 2020;24:413-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vranken JH. Mechanisms and treatment of neuropathic pain. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fava M. The role of the serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems in the treatment of psychological and physical symptoms of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64 Suppl 13:26-29. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Yajima R, Matsumoto K, Ise Y, Suzuki N, Yokoyama Y, Kizu J, Katayama S. Pregabalin prescription for terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialist palliative care in an acute hospital. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2016;2:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kroenke K, Wu J, Bair MJ, Krebs EE, Damush TM, Tu W. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal analysis in primary care. J Pain. 2011;12:964-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1911-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1349] [Cited by in RCA: 1606] [Article Influence: 84.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |