Published online Apr 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i4.101788

Revised: November 27, 2024

Accepted: February 8, 2025

Published online: April 24, 2025

Processing time: 180 Days and 23.6 Hours

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, presenting an increasing public health challenge, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. However, data on the knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices regarding breast cancer and the associated factors among females in Wollo, Ethiopia, remain limited.

To assess the impact of family history (FH) of breast disease on knowledge, attitudes, and breast cancer preventive practices among reproductive-age females.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in May and June 2022 in Northeast Ethiopia and involved 143 reproductive-age females with FH of breast diseases and 209 without such a history. We selected participants using the systematic random sampling technique. We analyzed the data using Statistical Package for Social Science version 25 software, and logistic regression analysis was employed to determine odds ratios for variable associations, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Among participants with FH of breast diseases, the levels of knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices were found to be 83.9% [95% confidence interval (CI): 77.9-89.9], 49.0% (95%CI: 40.8-57.1), and 74.1% (95%CI: 66.9-81.3), respectively. In contrast, among those without FH of breast diseases, these levels were significantly decreased to 10.5% (95%CI: 6.4-14.7), 32.1% (95%CI: 25.7-38.4), and 16.7% (95%CI: 11.7-21.8), respectively. This study also in

Educational status, monthly income, and community health insurance were identified as significant factors associated with the levels of knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices regarding breast cancer among reproductive-age females.

Core Tip: This study evaluated knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices related to breast cancer among reproductive-age females indicating the necessity for further study in this area. Data was collected using a structured questionnaire and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices related to breast cancer were significantly higher among participants with a family history of breast diseases. Educational status, monthly income, and community health insurance were significant factors associated with the levels of knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices re

- Citation: Agidew MM, Cherie N, Damtie Z, Adane B, Derso G. Impact of family history of breast disease on knowledge, attitudes, and breast cancer preventive practices among reproductive-age females. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(4): 101788

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i4/101788.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i4.101788

Cancer is a noncommunicable chronic disease and remains a significant global health challenge, contributing to high rates of morbidity and mortality universally. Based on the International Agency for Research on Cancer, approximately 14 million new cancer cases were reported[1]. Globally, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed disease in re

The prevalence of breast cancer is increasing, and it presents an escalating issue of public health specifically in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). In these countries, breast cancer ranks as the chief cause of death. In spite of the global continuing efforts to tackle risk factors and encourage preventive strategies, there is no female who is completely protected from being affected by breast cancer[2]. Currently, breast cancer incidence has exceeded that of lung cancer, with approximately 2.3 million new cases reported globally[3]. Incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer have increased over the last 30 years. Breast cancer incidence has more than doubled between 1990 and 2016[4]. The worldwide number of annually diagnosed new breast cancer cases and the number of breast cancer deaths will be 2.7 and 0.87 million, respectively, by 2023. Breast cancer incidence is expected to increase further in LMICs[5].

The median age of females in Libanos at which they present with breast cancer is 49 years, highlighting the critical importance of early detection and intervention[3]. The impact of breast cancer has increasingly extended to developing countries, posing a significant threat to public health, while it was historically more prevalent in developed nations. Frighteningly, almost half of all breast cancers and over half of the associated deaths take place in LMICs, underscoring the critical need for improved prevention and management strategies worldwide[3,5].

In Ethiopia, the incidence of newly diagnosed cancer cases is rising, and breast cancer is emerging as a prevalent cancer. It accounts for 33% of all female cancers and 23% of all cancer cases. The age-adjusted incidence rate of breast cancer among Ethiopian reproductive-age females is 41.8 cases per 100000 females. In 2012, about 12956 new breast cancer cases were diagnosed[6]. A study conducted in Addis Ababa discovered that breast cancer is the second most common cancer, accounting for 27.8% of all cancers[7].

Ethiopian health policy is being challenged significantly in cancer prevention and treatment, principally due to resource limitation and the prevailing focus on communicable diseases[7]. Raising awareness about breast cancer is crucial in influencing the time when patients seek medical assistance[8]. Studies showed that knowledge, attitudes, and breast cancer preventive practices can significantly affect the decisions of females to pursue health care[9].

Implementing the identification approaches for early detection is crucial for decreasing mortality due to breast cancer[10]. Early diagnosis allows for timely treatment before the disease becomes complicated, resulting in improved treatment outcomes. Attaining early detection involves enhancing awareness about breast cancer, promoting active healthcare participation, safeguarding precise diagnosis and appropriate pathological diagnoses, appropriately staging of the di

Breast cancer diagnosis and identification at its early stage are vital to improving treatment success rates, underscoring the importance of raising awareness about its symptoms. Understanding the knowledge, attitudes, and preventive measures related to breast cancer among reproductive-age females is essential for mitigating its impact. However, there is a notable lack of comprehensive information regarding breast cancer awareness, attitudes, and preventive practices within Ethiopian reproductive-age females[12]. This information gap indicates the urgent need for further study in the area. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the level of knowledge about breast cancer, attitudes towards it, and breast cancer preventive practices among the Ethiopian reproductive-age females and their associated factors.

The study team conducted this research in a district called Wadila, which is situated in Wollo, Ethiopia, from May 1, 2022 to June 30, 2022. Wadila is situated 320 kilometers east of Bahir Dar and 120 kilometers west of Woldia. There are 136407 individuals in Wadila district residing across 2 urban and 24 rural kebeles. About 50.2% of this population are female, including 32165 reproductive-age females. There is one district hospital and six healthcare facilities in the study area serving as principal health care facilities for the public.

A community-focused cross-sectional research strategy was employed for assessing reproductive-age female permanent residents of the study area living in the district throughout the study period.

All reproductive-age females who were permanent residents of the district and present during the data collection period were included in the study. Reproductive-age females with a history of breast cancer and those with visual, hearing, and/or speech impairments were excluded.

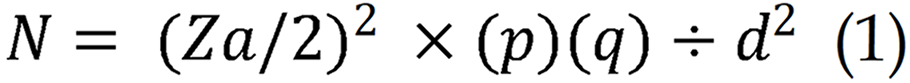

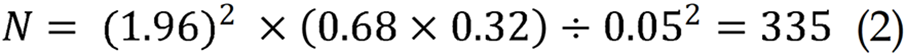

The study sample was calculated by the single-population proportion method, postulating that about 68% of females engaged in self-examination of their breast, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5% margin of error.

N is the required sample number, α is significance level (5%), Za/2 is Z (standard normal distribution value) at the designated level of significance (1.96), p is the proportion of females who practiced self-examination of the breast (68%), and d is the margin of error (0.05).

Then, by summing a 5% non-responsive proportion, the study sample was 352.

Five kebeles were selected in the district for this study using the random sampling technique. We employed systematic random sampling to determine the number of households in each kebele based on their population size. We applied an interval of independent sampling for individual kebeles. We allocated the sample size proportionally based on the number of households in each selected kebele. A single eligible reproductive-age female was randomly selected from each household in the cases where more than one eligible female was found per household.

We collected data using a structured questionnaire developed by reviewing previous peer-reviewed studies[12-15]. This questionnaire was administered by trained interviewers and underwent a pre-test to collect data to guarantee content validity. The questionnaire encompassed various variables aligned with study objectives, including sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge of breast cancer, attitude towards breast cancer, and practices related to breast cancer pre

The knowledge section comprised ten items, with correct answers scored as 1 point and incorrect answers as 0 points, yielding a hypothetical result 0-10 points. The attitude part assessed eight components using a Likert scale having five points [“very positive” (5 points) to "very negative” (1 point)], with a total probable result from 8-40 points. Similarly, the practice section contained eight items rated on the same 5-point Likert scale, also yielding a total score range of 8-40 points[16].

Good knowledge about breast cancer: The research team evaluated the knowledge of females about breast cancer based on the American Cancer Society reference guideline[1]. We considered the study subjects as having good knowledge if they answered at least the mean score of the knowledge assessment questions in our study[13].

Positive attitude: Our participants were considered as having a positive attitude towards cancer if they scored at least 20 on the attitude assessment questions in our study[16,17].

Breast cancer preventive practice: Females who practiced breast self-examination 7 days after every menstrual period by their own palm and the 3 middle fingers, or received a minimum of one scientific medical assessment of the breasts, or had not less than 1 breast screening examination using mammogram in their lifespan[1], or practiced at least half of the practice assessing check list[16] were indicated as practicing preventive care.

Knowledge, attitude, and breast cancer preventive practices were dependent variables, whereas sociodemographic factors (age, residency, religion, marital status, educational status, occupation, income, and community health insurance) and medical factors [family history (FH) of breast cancer and any breast disease] were independent variables.

We selected three female clinical nurses as data collectors based on their previous data collection experience to ensure data quality[12]. We trained them for 2 days on study objectives, interview techniques, and ethical considerations[13-15]. The questionnaire was meticulously designed by the researchers through a review of various peer-reviewed articles and tailored to align with our specific objectives[13-15]. Initially prepared in English, the questionnaire was subsequently translated into Amharic to facilitate effective communication. The research team conducted daily revisions of the collected data to check for errors, legibility, completeness, and consistency before entering it into the database for sta

The research team verified completeness, coded, and entered the data into Epi Data version 3.1, which was then exported into SPSS 25 statistical software to summarize and analyze. The researchers utilized statistical summary. Factors having a P value below 0.25 using bivariate logistic regression included in multivariate model for determining independent correlation. The researchers reported adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95%CI, and the significance point was established at P < 0.05[12].

The research team was given ethical approval and cooperation from Zemen Post Graduate College Coordinating Program Ethical Review Committee and Wadila District Health Office, respectively. Informed consent was secured from each study participant prior to data collection, ensuring confidentiality. The informed consent was obtained from their parents or caregivers if the participants were under 18 years of age.

In total, 24.5% of females with FH of breast diseases were aged 30-34 years, while 27.8% of females without FH fell within the 20-24 years age group. Among the participants, 76.2% with FH resided in rural areas compared with 56.5% of those without FH who lived in urban settings. Additionally, 30.8% of those with FH and 37.8% of those without had completed secondary education. Furthermore, 27.3% of those with FH and 28.2% of those without were engaged in farming activities (Table 1).

| Variables | Females with FH of breast diseases (n = 143) | Females without FH of breast diseases (n = 209) | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Age category (in years) | 15-19 | 28 | 19.6 | 47 | 22.5 |

| 20-24 | 20 | 14.0 | 58 | 27.8 | |

| 25-29 | 30 | 21.0 | 42 | 20.1 | |

| 30-34 | 35 | 24.5 | 49 | 23.4 | |

| ≥ 35 | 30 | 21.0 | 13 | 6.2 | |

| Residency | Rural | 109 | 76.2 | 91 | 43.5 |

| Urban | 34 | 23.8 | 118 | 56.5 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 106 | 74.1 | 148 | 70.8 |

| Others than orthodox | 37 | 25.9 | 61 | 29.8 | |

| Ethnicity | Amhara | 129 | 90.2 | 162 | 77.5 |

| Other than Amhara | 14 | 9.8 | 47 | 22.5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 56 | 39.2 | 82 | 39.2 |

| Married | 61 | 42.7 | 85 | 40.7 | |

| Divorced | 13 | 9.1 | 33 | 15.8 | |

| Widowed | 13 | 9.1 | 9 | 4.3 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 35 | 24.5 | 64 | 30.6 |

| Primary education | 21 | 14.7 | 49 | 23.4 | |

| Secondary education | 44 | 30.8 | 79 | 37.8 | |

| College/university | 43 | 30.1 | 17 | 8.2 | |

| Occupational status | Employee | 27 | 18.9 | 38 | 18.2 |

| Merchant | 32 | 22.4 | 35 | 16.7 | |

| Farmer | 39 | 27.3 | 59 | 28.2 | |

| Housewife | 27 | 18.9 | 37 | 17.7 | |

| Labor worker | 15 | 10.5 | 34 | 16.3 | |

| Jobless | 3 | 2.1 | 6 | 2.9 | |

The majority of participants in both groups (69.2% of participants with FH and 78.9% of those without) were living below the poverty line. Additionally, 80.4% of participants with FH of breast diseases had community health insurance compared with 58.4% of those without such a history. Among reproductive-age females with FH of breast diseases, 64.3% reported FH of breast cancer, while 35.7% had FH of other breast-related conditions (Table 2).

| Variables | Females with FH of breast diseases (n = 143) | Females without FH of breast diseases (n = 209) | |||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Monthly income | Below poverty line | 99 | 69.2 | 165 | 78.9 |

| Above poverty line | 44 | 30.8 | 44 | 21.1 | |

| Community health insurance | Yes | 115 | 80.4 | 122 | 58.4 |

| No | 28 | 19.6 | 87 | 41.6 | |

| FH of breast cancer | Yes | 92 | 64.3 | - | - |

| No | 51 | 37.5 | - | - | |

| Family history of other breast diseases | Yes | 51 | 35.7 | - | - |

| No | 92 | 64.3 | - | - | |

This study revealed a significant disparity in knowledge, attitudes, and breast cancer practices among reproductive-age females with and without FH of breast diseases. Specifically, 83.9% (95%CI: 77.9-89.9) of females with FH of breast diseases demonstrated good knowledge about breast cancer compared with only 10.5% (95%CI: 6.4-14.7) of those without such a history. Furthermore, 49.0% (95%CI: 40.8-57.1) of participants with FH exhibited a positive attitude toward breast cancer, while only 32.1% (95%CI: 25.7-38.4) of those without FH shared this perspective. Additionally, 74.1% (95%CI: 66.9-81.3) of females with FH engaged in preventive practices for breast cancer in contrast to just 16.7% (95%CI: 11.7-21.8) of those without FH (Table 3).

| Variables | Frequency (%) | P value | ||

| Females with FH of breast diseases (n = 143) | Females without FH of breast diseases (n = 209) | |||

| Knowledge | Good | 120 (83.9) | 22 (10.5) | 0.000c |

| Poor | 23 (16.1) | 187 (89.5) | ||

| Attitude | Positive | 70 (49.0) | 67 (32.1) | 0.001b |

| Negative | 73 (51.0) | 142 (67.9) | ||

| Preventive practice | Yes | 106 (74.1) | 35 (16.7) | 0.000c |

| No | 37 (25.9) | 174 (83.3) | ||

Educational status, income, and community health insurance were the variables having a P < 0.25 during bivariate analysis. They were fitted to a multiple logistic regression model to assess independent predictor variables of the level of knowledge using AORs with 95%CI. Multivariate logistic regression analysis also found all of these variables were independent significant predictors for the level of knowledge about breast cancer of reproductive-age females. Females who completed secondary education (AOR = 0.170, 95%CI: 0.200-0.400) and college/university (AOR = 0.004, 95%CI: 0.001-0.019) were more likely to have good knowledge about breast cancer compared with those who were unable to read. In addition, participants above the poverty line were more likely to have knowledge about breast cancer compared with their counterparts (AOR = 0.380, 95%CI: 0.180-0.820), and those who had community health insurance were more likely to have knowledge about breast cancer compared with their counterparts (AOR = 2.220, 95%CI: 1.130-4.340) (Table 4).

| Variables | Knowledge in frequency | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Good | Poor | |||||

| Educational status | Unable to read1 | 23 | 76 | |||

| Primary education | 16 | 54 | 1.020 (0.500-2.110) | 0.300 (0.110-0.840) | 0.210 | |

| Secondary education | 49 | 74 | 0.460 (0.250-0.820) | 0.170 (0.200-0.400) | 0.000c | |

| College/university | 54 | 6 | 0.034 (0.013-0.880) | 0.004 (0.001-0.019) | 0.000c | |

| Income | Below poverty line1 | 96 | 168 | 0.520 (0.320-0.850) | 0.380 (0.180-0.820) | 0.014a |

| Above poverty line | 46 | 42 | ||||

| Health insurance | Yes | 108 | 129 | 2.000 (1.240-3.210) | 2.220 (1.130-4.340) | 0.021a |

| No1 | 34 | 81 | ||||

Educational status, income, and community health insurance were factors that had a P < 0.25 when analyzed by bivariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis found these variables were independent significant predictors for the attitude of reproductive-age females towards breast cancer. Participants who completed secondary education were more likely to have a positive attitude towards breast cancer compared with those who were unable to read (AOR = 0.420, 95%CI: 0.260-0.770). Additionally, participants above the poverty line were more likely to have a positive attitude towards breast cancer compared with their counterparts (AOR = 0.400, 95%CI: 0.240-0.680), and those who had community health insurance were more likely to have a positive attitude towards breast cancer compared with their counterparts (AOR = 1.980, 95%CI: 1.190-3.300) (Table 5).

| Variables | Attitude | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| Educational status | Unable to read1 | 26 | 73 | |||

| Primary education | 28 | 42 | 0.530 (0.280-1.030) | 0.630 (0.310-1.290) | 0.205 | |

| Secondary education | 59 | 64 | 0.390 (0.220-0.680) | 0.420 (0.260-0.770) | 0.005b | |

| College/university | 24 | 36 | 0.530 (0.270-1.060) | 0.600 (0.290-1.250) | 0.174 | |

| Income | Below poverty line1 | 85 | 179 | 0.330 (0.200-0.540) | 0.400 (0.240-0.680) | 0.001b |

| Above poverty line | 52 | 36 | ||||

| Health insurance | Yes | 105 | 132 | 2.060 (1.280-3.340) | 1.980 (1.190-3.300) | 0.009b |

| No1 | 32 | 83 | ||||

The study found that educational status, income, and community health insurance were study variables whose P < 0.25 in bivariate analysis. Thus, these variables were fitted with the multiple logistic regression model for assessing the independent predictor factors of preventive practice. The multivariate logistic regression analysis found that these variables were independent significant predictors for breast cancer preventive practices. Females who completed secondary education (AOR = 0.390, 95%CI: 0.200-0.770) and those with college/university education (AOR = 0.250, 95%CI: 0.110-0.540) were more likely to do preventive practices compared to participants who were unable to read. Furthermore, participants above poverty line were more likely to undergo preventive practice compared with their counterparts (AOR = 0.460, 95%CI: 0.250-0.860), and those having health insurance were more likely to conduct preventive practices compared with their counterparts (AOR = 4.590, 95%CI: 2.550-8.260) (Table 6).

| Variables | Preventive practice | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Yes | No | |||||

| Education status | Unable to read1 | 29 | 70 | |||

| Primary | 22 | 48 | 0.900 (0.470-1.760) | 0.630 (0.290-1.350) | 0.236 | |

| Secondary | 55 | 68 | 0.510 (0.290-0.900) | 0.390 (0.200-0.770) | 0.007b | |

| College/university | 35 | 25 | 0.300 (0.150-0.580) | 0.250 (0.110-0.540) | 0.000c | |

| Income | Below poverty line1 | 88 | 176 | 0.230 (0.140-0.390) | 0.460 (0.250-0.860) | 0.014a |

| Above poverty line | 53 | 35 | ||||

| Health insurance | Yes | 120 | 117 | 4.590 (2.680-7.860) | 4.590 (2.550-8.260) | 0.000c |

| No1 | 21 | 94 | ||||

This study revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices regarding breast cancer among reproductive-age females and their FH of breast diseases. Our findings align with previous research[12,18]. Notably, females with FH of breast diseases exhibited significantly higher levels of knowledge, more favorable attitudes, and enhanced preventive practices compared with those without FH of breast diseases. This observation is consistent with earlier studies[12,19]. The strong positive correlations among knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices in reproductive-age females with FH of breast diseases suggest that awareness of breast cancer increases in this group[12,19-21]. Therefore, it is essential to recognize that knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices regarding breast cancer differ between females with and without FH of the disease. This underscores the importance of assessing these factors separately for each group. However, our findings contrast with another study that found no significant differences in knowledge and attitudes between females with and without FH of breast diseases[18]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the more rural setting of our study area, where females are likely to develop app

Educational attainment, income level, and community health insurance emerged as significant factors influencing the knowledge of reproductive-age females regarding breast cancer. Multiple logistic regression analysis conducted in this study revealed that females who had completed secondary education or higher were significantly more likely to possess a good understanding of breast cancer compared with those who were unable to read. This finding is consistent with results from various prior studies[16,22,23].

Additionally, our research indicated that participants living above the poverty line demonstrated a greater likelihood of having a good level of knowledge about breast cancer compared to their less affluent counterparts. This outcome is supported by previous studies conducted among females[15,24]. Furthermore, the study found that participants with community health insurance were also more likely to exhibit a good understanding of breast cancer compared with those without such coverage. These findings agree with earlier research[25,26].

This study similarly confirmed that educational attainment, income level, and community health insurance are significant factors influencing the attitudes of reproductive-age females toward breast cancer. Participants who had completed secondary education or higher were more likely to exhibit a positive attitude toward breast cancer compared with those who were unable to read. This finding is consistent with previous research[23]. Additionally, females living above the poverty line demonstrated a more positive attitude toward breast cancer than their less affluent counterparts, a result supported by a study conducted among females in China[16]. However, our findings diverge from the previous study, which may be attributed to the lack of significant economic disparities in that context[25,26]. Furthermore, re

Lastly, our study identified several significant factors influencing the adoption of breast cancer preventive practices among reproductive-age females. Participants who had completed secondary education or higher were more engaged in these preventive practices compared to participants unable to read. The finding of this study is consistent to a study conducted in females of reproductive age in various regions[17,23,27]. Furthermore, females living above the poverty line demonstrated a higher likelihood of participating in breast cancer preventive practices than their lower-income coun

The primary strength of this study was its originality, as it provides valuable insights into the knowledge, attitudes, and breast cancer preventive practices of the Ethiopian reproductive-age females. The present research could be used as a baseline for detailed studies in the future in this area. Yet, this research faced certain limitations. One notable challenge was obtaining responses from participants, as many residents in the study area felt embarrassed to engage in face-to-face interviews and were reluctant to provide candid answers to some questions. Consequently, there may be an element of social bias, despite the anonymity of the survey and the use of female interviewers. Additionally, being a cross-sectional study, it was unable to establish causal relationships between the variables examined.

This study revealed statistically significant differences in the levels of knowledge, attitudes, and breast cancer preventive practices among reproductive-age females with and without FH of breast diseases. Participants with FH of breast diseases demonstrated significantly higher levels of knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices compared with those without such a history. Furthermore, factors such as educational status, monthly income, and community health insurance were found to be significantly associated with knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices regarding breast cancer among reproductive-age females.

We would like to express our wholehearted gratitude to Zemen Postgraduate College for its support for this study. We also would like to acknowledge the study participants and data collectors for their precious support.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64217] [Article Influence: 16054.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (174)] |

| 2. | Ginsburg OM. Breast and cervical cancer control in low and middle-income countries: Human rights meet sound health policy. J Cancer Policy. 2013;1:e35-e41. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fares MY, Salhab HA, Khachfe HH, Khachfe HM. Breast Cancer Epidemiology among Lebanese Women: An 11-Year Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55:463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma R. Breast cancer incidence, mortality and mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) are associated with human development, 1990-2016: evidence from Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Breast Cancer. 2019;26:428-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Porter P. "Westernizing" women's risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Solomon S, Mulugeta W. Diagnosis and Risk Factors of Advantage Cancers in Ethiopia. J Cancer Prev. 2019;24:163-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haileselassie W, Mulugeta T, Tigeneh W, Kaba M, Labisso WL. The Situation of Cancer Treatment in Ethiopia: Challenges and Opportunities. J Cancer Prev. 2019;24:33-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Green SMC, Lloyd KE, Smith SG; ENGAGE investigators. Awareness of symptoms, anticipated barriers and delays to help-seeking among women at higher risk of breast cancer: A UK multicentre study. Prev Med Rep. 2023;34:102220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Azubuike S, Okwuokei S. Knowledge, attitude and practices of women towards breast cancer in benin city, Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:155-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Black E, Richmond R. Improving early detection of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: why mammography may not be the way forward. Global Health. 2019;15:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Croswell JM, Ransohoff DF, Kramer BS. Principles of cancer screening: lessons from history and study design issues. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:202-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Damtie Z, Cherie N, Agidew MM. Breast cancer preventive practices and associated factors among reproductive age women in Wadila District, North East Ethiopia: community based cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mehiret G, Molla A, Tesfaw A. Knowledge on risk factors and practice of early detection methods of breast cancer among graduating students of Debre Tabor University, Northcentral Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lera T, Beyene A, Bekele B, Abreha S. Breast self-examination and associated factors among women in Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Abeje S, Seme A, Tibelt A. Factors associated with breast cancer screening awareness and practices of women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu S, Zheng S, Qin M, Xie Y, Yang K, Liu X. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward ultrasound screening for breast cancer among women. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1309797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Koech JM, Magutah K, Mogere DM, Kariuki J, Willy K, Muriira MA, Chege H. Knowledge, attitude and practices around breast cancer and screening services among women of reproductive age in Turbo sub-county, Kenya. Heliyon. 2024;10:e31597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Bird Y, Moraros J, Banegas MP, King S, Prapasiri S, Thompson B. Breast cancer knowledge and early detection among Hispanic women with a family history of breast cancer along the U.S.-Mexico border. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:475-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu L, Hao X, Song Z, Zhi X, Zhang S, Zhang J. Correlation between family history and characteristics of breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seiffert K, Thoene K, Eulenburg CZ, Behrens S, Schmalfeldt B, Becher H, Chang-Claude J, Witzel I. The effect of family history on screening procedures and prognosis in breast cancer patients - Results of a large population-based case-control study. Breast. 2021;55:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Khushalani JS, Qin J, Ekwueme DU, White A. Awareness of breast cancer risk related to a positive family history and alcohol consumption among women aged 15-44 years in United States. Prev Med Rep. 2020;17:101029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kinteh B, Kinteh SLS, Jammeh A, Touray E, Barrow A. Breast Cancer Screening: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices among Female University Students in The Gambia. Biomed Res Int. 2023;2023:9239431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rakhshani T, Dada M, Kashfi SM, Kamyab A, Jeihooni AK. The Effect of Educational Intervention on Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Women towards Breast Cancer Screening. Int J Breast Cancer. 2022;2022:5697739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Afaya A, Japiong M, Konlan KD, Salia SM. Factors associated with awareness of breast cancer among women of reproductive age in Lesotho: a national population-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hastuti S. Breast Cancer Screening Access Among Low-Income Women Under Social Health Insurance: A Scoping Review. Public Health Indones. 2024;10:21-32. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Lamichhane B, Adhikari B, Poudel L, Pandey AR, Kakchhapati S, K C SP, Giri S, Dulal BP, Joshi D, Gautam G, Baral SC. Factors associated with uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening among Nepalese women: Evidence from Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2022. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024;4:e0002971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Biswas S, Syiemlieh J, Nongrum R, Sharma S, Siddiqi M. Impact of Educational Level and Family income on Breast Cancer Awareness among College-Going Girls in Shillong (Meghalaya), India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21:3639-3646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Toan DTT, Son DT, Hung LX, Minh LN, Mai DL, Hoat LN. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Breast Cancer Early Detection Among Women in a Mountainous Area in Northern Vietnam. Cancer Control. 2019;26:1073274819863777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |