Published online Feb 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i2.97107

Revised: September 4, 2024

Accepted: November 8, 2024

Published online: February 24, 2025

Processing time: 202 Days and 5.4 Hours

Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is a polyposis condition with neoplastic potential, but its psychological impact is not well understood.

To assess health anxiety prevalence in a regional Australian cohort of SPS patients and explore factors influencing it, including workforce impacts of regular sur

This cross-sectional study screened patients aged 18-65 undergoing colonoscopy in a regional gastroenterology practice between January 2015 and June 2022. Eligible SPS patients were invited to participate. Data included the Short Health Anxiety Inventory, employment status, and previous demographic and medical findings.

Health anxiety was found in 21.57% of SPS patients, with anxious patients being significantly more concerned about surveillance (OR = 7.70). Patients lost an average of 11.04 work hours per colonoscopy.

Health anxiety in SPS patients aligns with rates in other gastroenterology po

Core Tip: Health anxiety in serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) patients is similar to other gastroenterology patients. Loss of work due to scheduled colonoscopy bears consideration, especially given increased rate of SPS diagnosis.

- Citation: Thompson A, Dierick NR, Heiniger L, Kostalas SN. Health anxiety and work loss in patients diagnosed with serrated polyposis syndrome: A cross sectional study. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(2): 97107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i2/97107.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i2.97107

Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is a clinical condition characterized by the presence of multiple serrated lesions in the colorectum. These lesions have the potential to progress to neoplasia via the serrated pathway, accounting for 15%-30% of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) cases[1,2]. CRC is one of the most prevalent solid cancers in Australia[3]. While research has focused on understanding the etiology and predictors of SPS, it is equally important to consider the impact of an SPS diagnosis on a patient’s health anxiety in the context of holistic medicine. This understanding is crucial for optimizing patient management strategies. Additionally, the economic burden on individuals and the broader community due to work time lost in surveillance colonoscopic procedures remains unknown.

SPS is the most common polyposis syndrome with a reported prevalence of up to 1: 35[4]. Despite this, it is thought to be severely underdiagnosed with one study showing up to 24% of SPS diagnoses are missed[5]. This was thought to be due to unavailability of previous pathology and endoscopy reports, and failure of clinicians to correctly apply the diagnostic criteria.

Furthermore, sessile serrated lesions (SSL) are missed more often than other lesions due to their flat appearance and indistinct borders[6].

SPS is characterised by the presence of numerous colorectal serrated lesions[7]. Lifetime risk for developing CRC in patients diagnosed with SPS is almost 50%[8,9]. The underlying aetiology for SPS is unclear, however it is possible some parts of the serrated pathway have genetic components[10]. Clinicians rely on clinical criteria listed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to make a diagnosis as outlined: (1) ≥ 5 serrated lesions proximal to the rectum, all being ≥ 5 mm in size, with ≥ 2 being ≥ 10 mm in size and/or (2) > 20 serrated lesions/polyps of any size distributed throughout the large bowel, with ≥ 5 being proximal to the rectum[7].

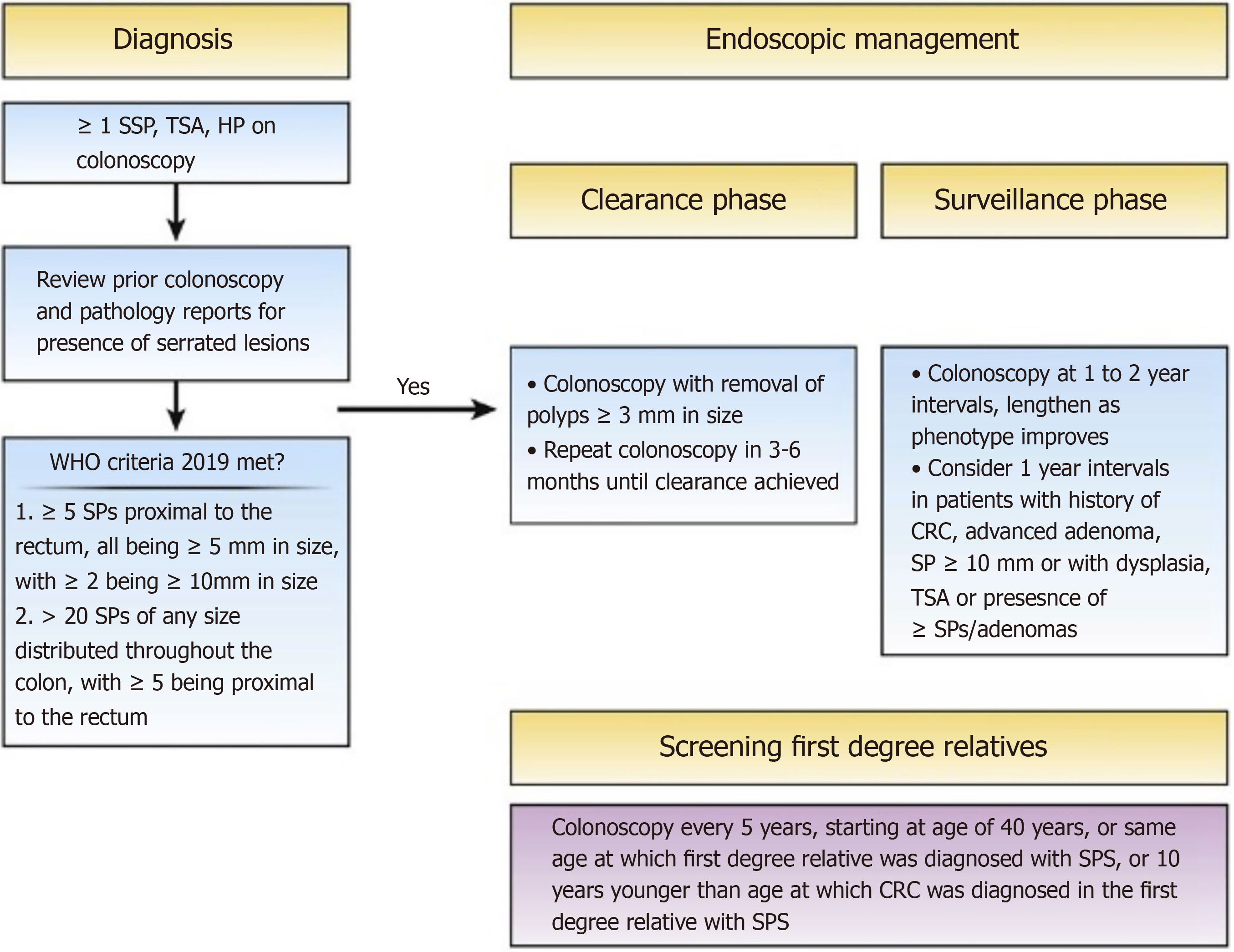

Diagnosis of SPS using these criteria can influence the way in which management is conducted, as these classifications indicate specific phenotypes of SPS with different CRC risk: Proximal with several large lesions, a more widespread distal version, and a mix of both[7]. Once a diagnosis has been made, management includes a clearance and surveillance phase as indicated in Figure 1. The surveillance phase should be personalised to each patient dependent on the phenotype assessed, with patients with less numerous serrated lesions having longer surveillance intervals to reduce colonoscopy burden[8].

Most of the epidemiological data surrounding SPS was based on previous WHO clinical criteria which included family history of SPS, this criterion was removed in the WHO 2019 update[7]. These studies estimate SPS prevalence of up to 2.94%, but the range in variable with 0.9% in FOBT screening cohorts, 0.4% in primary screening cohorts and between 0.4%-0.8% in colonoscopy surveillance cohorts[4,7,11,12]. This is far above the regularly quoted but outdated figure of 1 in 3000 people screened 13 likely as a result of better understanding of serrated lesion’s role in CRC pathogenesis, more awareness of SPS from endoscopists, implementation of international quality control standards for colonoscopy performance, advancements in endoscopic image technology, introduction of systematic tracking of serrated lesions, use of split bowel preparation, and widespread adoption of population-based screening programs[7,11,13,14].

Both current and previously reported prevalence rates suffer from detection bias due to missed polyps and diagnosis[14,15]. Hetzel et al[14] estimates that detection rates of proximal SSL between 2006 and 2008 rose from 0.2 per 100 patients with at least one polyp to 4.4, and that the detection rates of hyperplastic polyps and traditional serrated adenomas significantly differ among endoscopists.

Further, Kahi et al[15] found with 15 gastroenterologists that detection of any proximal serrated lesion was dependent on the performing endoscopist and not patient age or gender.

The mean age of diagnosis of SPS is found consistently to be between 50 and 60 years[9,16,17]. However, as the diagnostic criteria is cumulative over the patient’s lifetime, average age may be skewed towards older ages due to patients just meeting diagnostic criteria at older ages due to sporadic serrated lesions.

SPS is more common among men, however not statistically significantly[18]. 69.5% of SPS patients are obese and 74.4% are smokers as found by Carballal et al[17]. Carballal et al[17] also found that 29.4% of SPS patients had a first-degree relative (FDR) diagnosed with CRC. The study also found 4.4% of FDR had SPS. Familial association of SPS is limited and varied between studies. A study by Hazewinkel et al[10] found that 14% of FDRs were diagnosed with SPS. Further, Win et al[19] measured incidence of CRC in first and second degree relatives acting as a proxy for SPS, observing that FDR had a 5.17 standardised incidence ratio (SIR) and second degree relatives had a 1.38 SIR. Despite this there is little evidence from genomic wide association studies to support a gene responsible for SPS predisposition[20].

There are several risk factors for the development of serrated lesions. Bailie et al[21] found that increasing age, smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, diabetes and red meat intake were significantly associated with increased risk of lesions. Aspirin and non-steroidal anti- inflammatory medications were associated with a reduction in serrated lesions[21,22].

Health anxiety is outlined in the DSM 5 as Illness Anxiety Disorder: “the preoccupation with having or acquiring a serious, undiagnosed medical illness” with specific criteria required for diagnosis[23]. However, studies often do not ask questions specifically to address these criteria, and instead use a variety of different health surveys, or illness specific questions answered on a Likert scale[24,25]. Lebel et al[25] systematically reviewed 401 studies that measured health anxiety in specific chronic illnesses. Many of these studies used illness specific questions on a Likert scale, limiting cross-disease generalizability. It was found that a concept of health anxiety was highly prevalent across these studies.

In Australia, health anxiety was found to be prevalent in 5.7% of the population in the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing[26], where it was found to be significantly associated with more stress, impairment, disability and health service utilisation. Greater health service utilisation by those with health anxiety was also found by Tyrer et al[27] whose findings showed that 1 in 5 people (19.8%) attending British medical clinics exhibited clinically significant health anxiety. Specifically in gastroenterology clinics, this figure was similar (19.5%).

In a study of patients with ulcerative colitis, Oxelmark et al[28] found no increased anxiety when undergoing co

The HAI can differentiate persons with severe health anxiety and those with significant but not debilitating health anxiety[35]. Further, it has two short versions, Short HAI (SHAI)-14 and with negative consequence questions the SHAI-18, that both have very good internal consistency with the longer version (Supplementary material)[33].

Importantly, this study provides insight into the level of health anxiety experienced by patients diagnosed with SPS and allows for a quantitative assessment of the amount of work time lost for colonoscopy surveillance of this disease.

Research questions: What is the prevalence of health anxiety in patients with SPS in a regional Australian cohort? What are the clinical factors of SPS patients with health anxiety?

Research objectives: Collect data on health anxiety in working aged adult patients (≥ 18 and < 65 years of age) who meet the WHO criteria for SPS using SHAI-18. Describe clinical factors of SPS patients with health anxiety. Identify work lost for SPS patients as a result of colonoscopy screening. Evaluate link between patients’ perspective on personalised surveillance and health anxiety.

This is a single-centre study with data prospectively collected from patients under 65 who meet SPS criteria in a regional Australian gastroenterology practice. All patients undergoing colonoscopy at Port Macquarie Gastroenterology and Endoscopy between January 2015 and June 2022 were screened for this study. Consent for colonoscopy and demographic data collection was obtained at time of consent for colonoscopy. Routine pre-endoscopy demographic details, clinical history and examination details were recorded using practice software for all patients (Genie version 9.2.2., Magic Carpet Software Solutions). These data were compiled with size and locations of SSLs from histopathological reports and recorded in an excel database. Further data collection was via telephone interview with SHAI-18 and employment questions, with consent for the further data collection obtained verbally at the time of phone call.

Inclusion criteria: Eligible working aged adults are those aged 18 years or older and less than 65 years of age, who have been diagnosed with SPS according to the WHO definition.

Exclusion criteria: Patients who do not consent to data collection or who cannot be contacted will be excluded.

Diagnosis of SPS was made in accordance with the WHO 2019 criteria. Health anxiety was measured using a total score of the SHAI-18 with each question given a score of 0-3. Patients who had multiple answers for a question or answered as between two choices were record as the higher scored item.

Patients were sent an SMS prior to phone call to indicate they would be called. Upon calling, consent was obtained, and then each question of the SHAI-18 was read in entirety before patients answered. Scores (0-3) corresponding with answers to each question were recorded in an excel database.

Patients were asked two questions after the SHAI as follows: Are you currently working, and if so are you full time, part time or casual? In relation to your last colonoscopy appointment, did you take any days off from work? If so how many? To calculate hours of work, full-time was equated to a 40-hour work week, part-time a 30- hour work week, and casual a 20-hour work week. Using the results from question 20, hours lost on average per colonoscopy appointment can be calculated.

Patients were also asked the following study specific multiple-choice question to indicate their opinion on personalised surveillance. This was scored 0-3.

This final question is in reference to surveillance and screening programs (like colonoscopies becoming more personalised or individualised depending on a variety of factors including severity of disease, lifestyle, genome and microbiome).

I would not worry about my health if surveillance/screening programs were personalised to my health.

I would be slightly worried about my health if surveillance/screening programs were personalised to my health.

I would be worried about my health if surveillance/screening programs were personalised to my health.

I would be very worried about my health if surveillance/screening programs were personalised to my health.

A review of the literature on health anxiety identified possible clinical and demographic factors that may influence health anxiety. These are outlined in Table 1.

| Demographic | Clinical |

| Age | Smoking |

| Sex | Ethanol |

| Working status | Number of medications |

| Family history of CRC | |

| Personal history of CRC | |

| Years since diagnosis |

Clinical factors were extracted from patients’ clinical records. These included clinician notes and endoscopic reports.

All patients aged 18 years or older and less than 65 years at the time of data collection.

R software was used to analyse data (2023.12.1 Build 402). Descriptive statistics were used to outline the prevalence and clinical factors of the cohort. Clinical factors included age, sex, family history of first degree relative with CRC, previous CRC, smoking status, and ethanol consumption Personalised surveillance attitude was analysed using a logistic regression against health anxiety score.

Ethics approval for this study comes under Refence Number: EQ C1A 19 052 provided by the Social Sciences and Hu

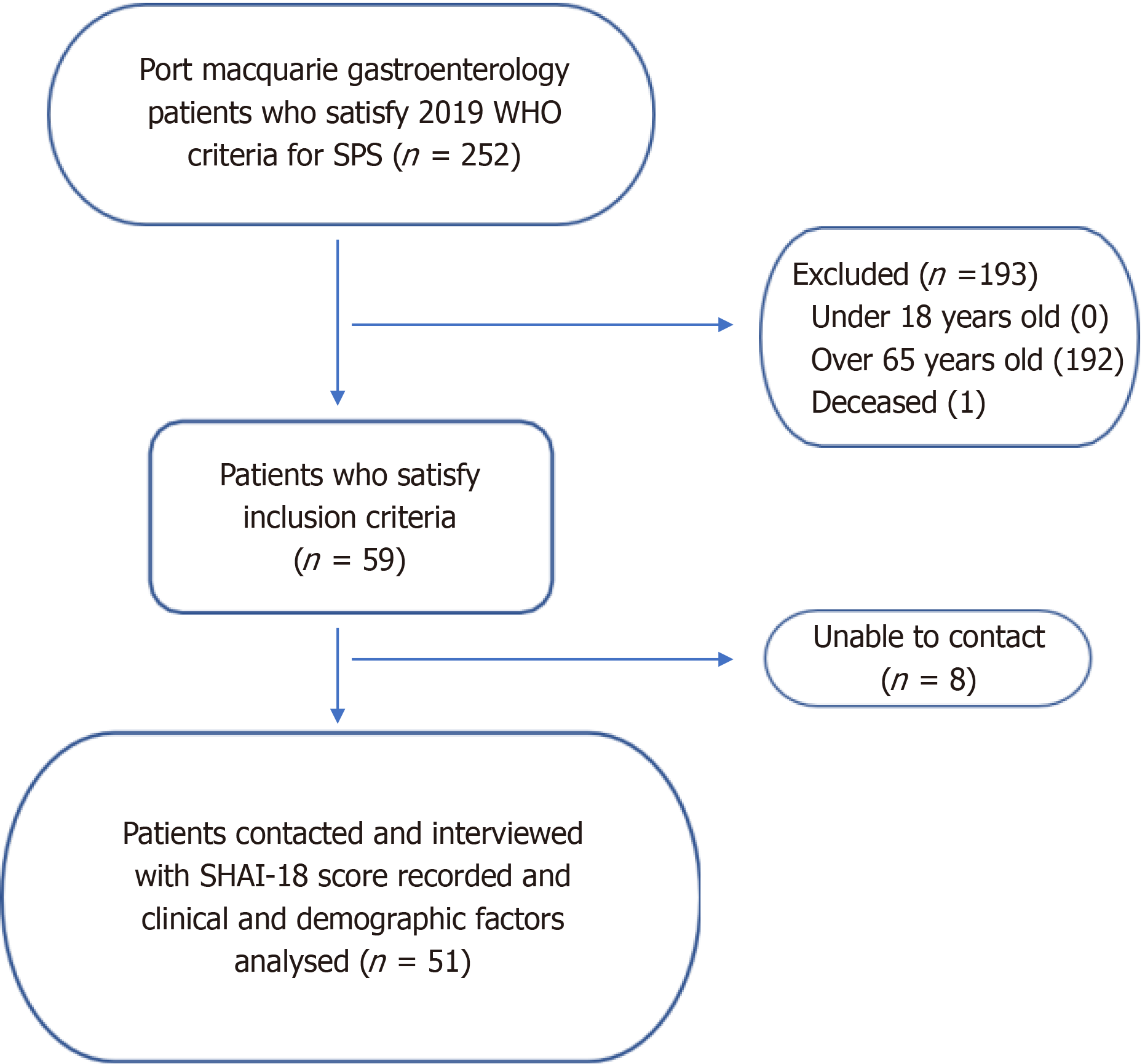

Two hundred and fifty-two patients were diagnosed with SPS between January 2015 and June 2022 at Port Macquarie Gastroenterology through colonoscopies. Patients under the age of 18 (0), over the age of 65 (192) and those who declined consent (0) were excluded from the study. One patient was deceased at the time of data collection. The resultant 59 patients were all contacted via text and then telephone, however 8 people did not answer, so have also been excluded from results. The flowchart for recruitment can be seen in Figure 2.

Of the patients interviewed for the study, there were no missing data points within the survey questions. Two patients did not have a fully updated clinical record, so clinical characteristics including family CRC history, personal CRC history, FOBT status, smoking status and Ethanol intake were missing. However, this is only 3.96% of the patient cohort.

Characteristics of the study population are outlined in Table 2. The majority of the patients were female (70.59%). Men (M) age of diagnosis was 48.14 years with a SD of 10.88 years. First degree family history of CRC was 29.41%, with a further 17.65% with second degree family history. Most patients (94.12%) did not have a personal history of CRC, with only 1 (1.96%) having CRC prior to diagnosis of SPS. 70.59% of patients did not smoke, with 17.65% of patients being ex-smokers, and 7.84% being current smokers. Of the cohort, 13.73% consumed > 30 gm of ethanol per day. Finally, only 2 patients were not employed, with the majority (64.71%) being full time employed, 23.53% were part time, and 7.84% were casual.

| n (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 15 (29.41) |

| Female | 36 (70.59) |

| Age at SPS diagnosis (years), mean | 48.14 |

| SD | 10.88 |

| Range | 23-62 |

| Family history of CRC | |

| 1st degree | 15 (29.41) |

| 2nd degree | 9 (17.65) |

| No | 23 (45.10) |

| Unknown | 2 (3.92) |

| Missing data | 2 (3.92) |

| Previous history of CRC | |

| CRC prior to Dx of SPS | 1 (1.96) |

| CRC at time of SPS Dx | 0 (0) |

| CRC post SPS Dx | 0 (0) |

| No CRC | 48 (94.12) |

| Missing data | 2 (3.92) |

| Smoking status | |

| Yes | 4 (7.84) |

| No | 36 (70.59) |

| Ex-smoker | 9 (17.65) |

| Missing data | 2 (3.92) |

| Ethanol intake (> 30 gm per day) | |

| Yes | 7 (13.73) |

| No | 42 (82.35) |

| Missing data | 2 (3.92) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 33 (64.71) |

| Part-time | 12 (23.53) |

| Casual | 4 (7.84) |

| Not working | 2 (3.92) |

In total, 11 (21.57%) patients interviewed scored greater than or equal to 18, corresponding with clinically significant health anxiety, with 1 (1.96%) scoring greater than or equal to 30, indicating hypochondriasis. The mean SHAI-18 score of patients was 13.43 (SD = 6.16). Men (M = 13.87) and women (M = 13.25) scored very similarly. Younger people scored lower than those aged above 45 (12.17 compared to 13.82). These are seen in Table 3.

| Mean (SD), range | |

| Total sample | 13.43 (6.16), 2-30 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 13.87 (5.55), 7-25 |

| Female | 13.25 (6.46), 2-30 |

| Age | |

| < 45 years | 12.17 (8.04), 5-30 |

| ≥ 45 years | 13.82 (5.12), 2-25 |

| Health anxiety (%) | |

| Score ≥ 18 | n = 11 (21.57) |

| Score ≥ 30 | n = 1 (1.96) |

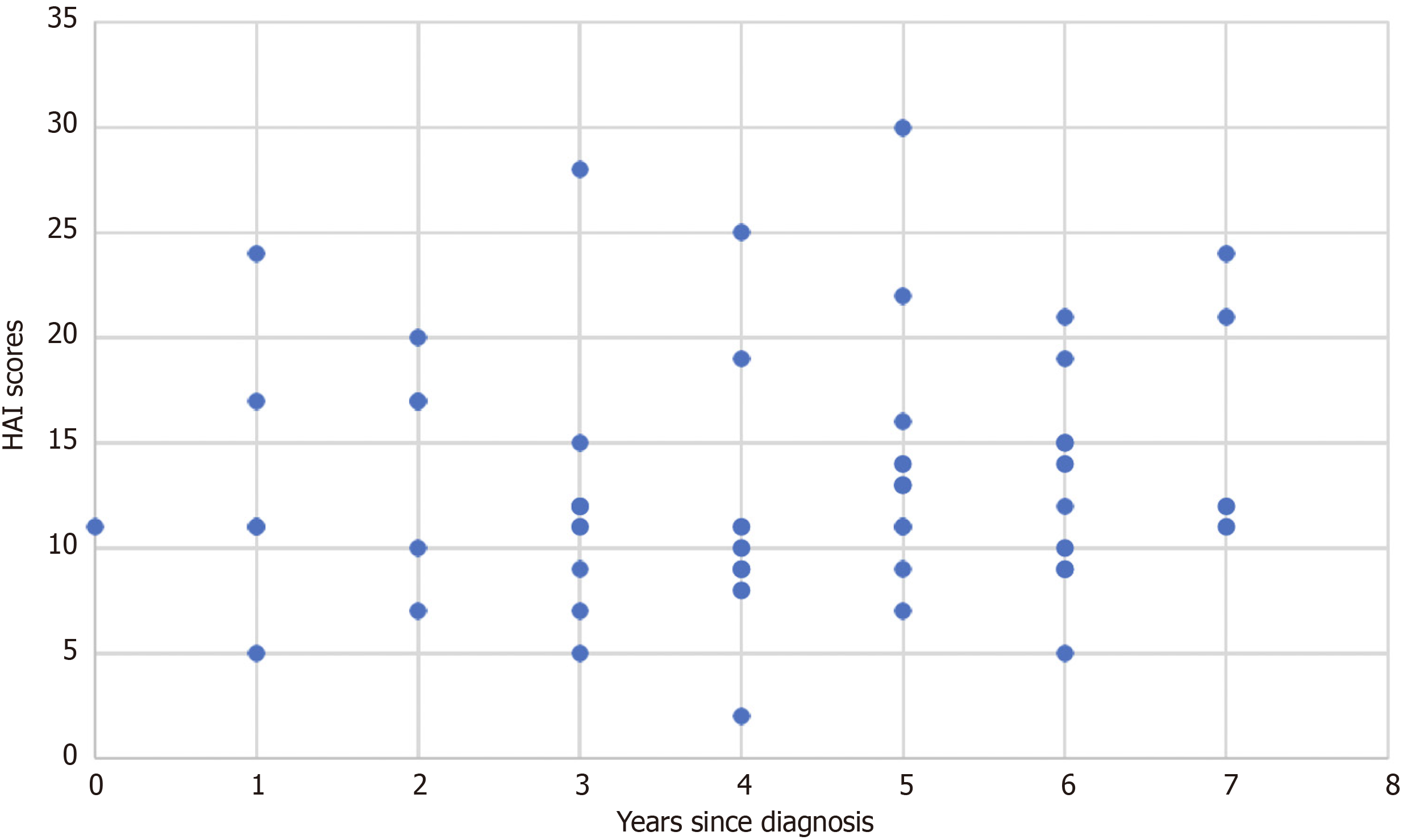

Further, health anxiety scores as a function of years since diagnosis was visualised in the following graph, with no obvious link being seen (Figure 3).

Employment status was outlined in the above Table 2. On average, a patient lost 11.14 (SD = 11.07) hours of work for their most recent colonoscopy.

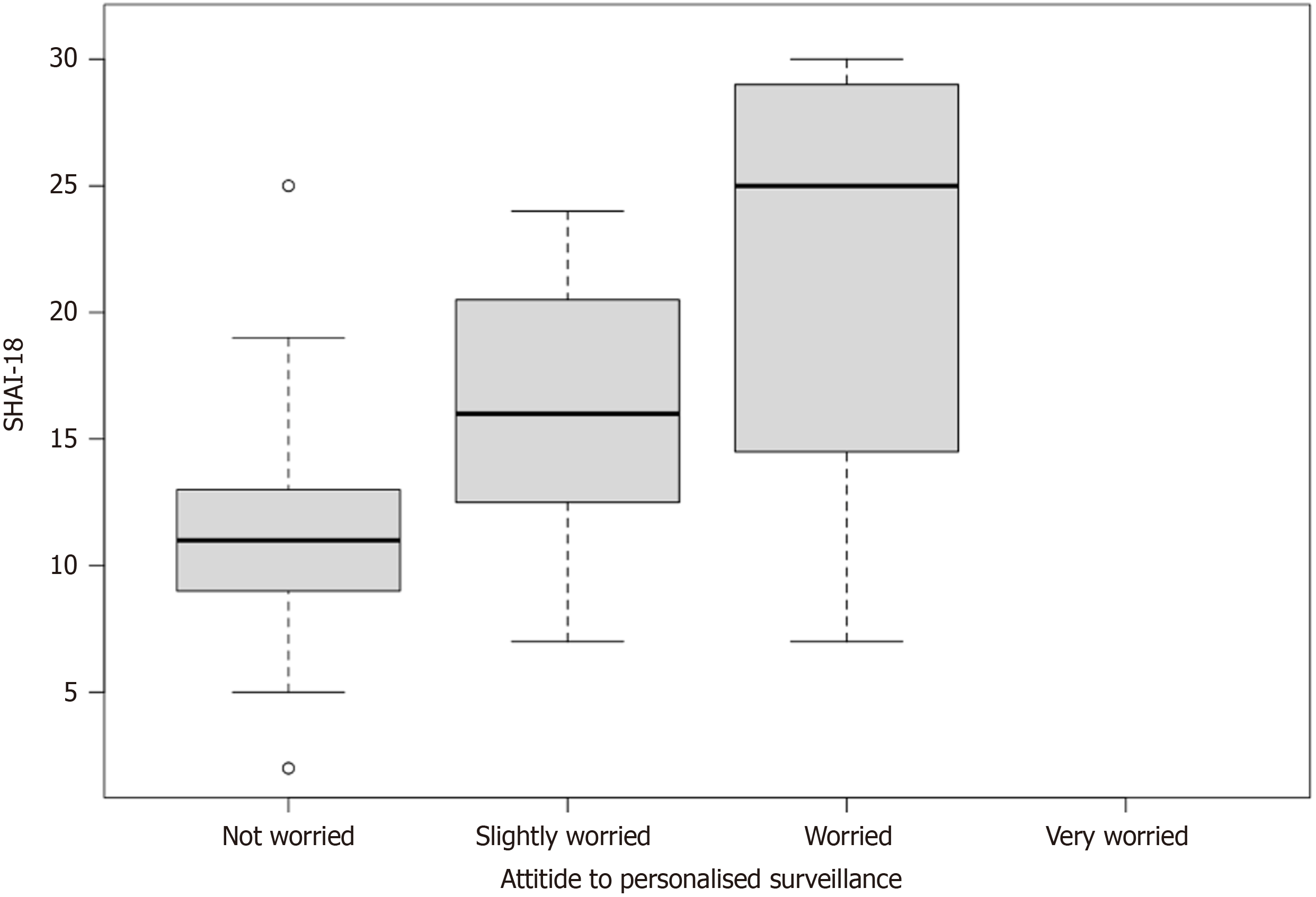

While 63% of patients were not worried about their health if surveillance was personalised to them. When performing a logistic regression using a SHAI-18 score of above 18 as Health Anxiety, Health Anxiety was associated with increased worry about health due to personalised surveillance as shown in Table 4. This can be relationship can be visualised in Figure 4 with a box and whisker plot of each response and the range of health anxiety scores associated with each.

In this cross-sectional study, the health anxiety of patients diagnosed with SPS was successfully measured using a standardised questionnaire. It is important to recognise health anxiety as it can have substantial effects on society and patients’ health. Health anxious patients are significantly more likely to take long term sick leave, have a disability pension award and utilise far more healthcare services[37-39]. Further, health anxiety has been linked to an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease[40]. Therefore, it is important to identify and treat health anxiety.

In this study, the SHAI-18 was used, with cut off scores for health anxiety and hypochondriasis set at ≥ 18 and ≥ 30 respectively, as specified by the scale developers[35]. This resulted in a health anxiety prevalence of 21.5%, and hypo

Tyrer et al[27] measured health anxiety prevalence in British medical clinics, finding 19.5% of patients attending gastroenterology clinics had health anxiety. However, they used a cut-off score of 20, so comparisons to the findings of this study are limited.

It may be more meaningful to compare mean scores from this study to other samples. For example, Salkovskis et al[35] found the mean score of health anxiety in gastroenterology clinics to be 13.9 (SD = 7.4), similar to the mean found in this study of 13.43. Tyrer et al[27] did not publish a mean for their sample. Overall in comparing to a non-clinical sample, Alberts et al[33] suggests comparing to their pooled mean of 12.41 (SD = 6.81), a full point lower this studies score.

Worry regarding personalised surveillance for patients was associated with health anxiety. Patients who had SHAI-18 scores above 18 were significantly more likely to be more worried about their health if they were to have tailored surveillance. However, this question was poorly worded for patients and there were some significant issues when asking this, with some patients not fully understanding it without a lengthy explanation. Nevertheless, this is an important finding that links with Tarr et al[30] suggesting that patients with lower anxiety are more likely to make better lifestyle and medical choices, being more agreeable to personalised surveillance colonoscopies. Further, it is in accord with Berian et al[29] who linked reduction in anxiety due to colonoscopy surveillance.

This study has also shown employment has been affected substantially due to surveillance procedures, with over 11 hours of work lost per colonoscopy. At median wage in Australia ($36 an hour), this equates to an average of $401.04 lost earnings per patient per colonoscopy. As SPS patients require more regular surveillance intervals than other patients, this could indicate a significant impact on individual and societal costs.

The strengths of this study come from the use of the SHAI-18 as a principal measurement tool, due to its widespread use and high validity[36]. The use of telephone interviews further helped the study as there were no missing data in the questionnaire, and a high percentage of the study’s proposed cohort (86.4%) was contactable and responded.

However, limitations of this study are clear, and further research is required to fully elucidate the effects of SPS on health anxiety. The upper limit on age of recruitment is unsupported in the literature and should be expanded to gather a full picture of the SPS cohort. Further, while the use of a published survey requires less reliance on a control group, as other studies can be used for comparison, limitations are met when realising slight variances in the survey used (SHAI-14 vs -18), the cut off score used, and the mode of delivering the survey. Erhart et al[41] found that while telephone surveys are valid and reliable, patients are likely to report more positive outcomes via telephone than through other forms of survey. While response rate may drop, if this study was expanded to the larger cohort of SPS patients, a more robust method of interviewing should be utilised.

This study demonstrated there is a prevalence of health anxiety in SPS patients that is similar to previous general clinical samples of gastroenterology patients. However, this is still substantially higher than general population, and should be used to help guide management. This study also elucidated that patients with health anxiety are more likely to be worried about personalised surveillance. Further, this study has shown that regular screening has a substantial impact on patients’ ability to work in the days surrounding a colonoscopy.

Further research should be conducted to expand this cohort to gather a better understanding of the overall prevalence of health anxiety in SPS patients and identify key areas where patients believe their care could be improved.

The idea for this study was provided to A/Prof Kostalas by Professor B Leggett and Dr N Tutticci.

| 1. | Huang CS, Farraye FA, Yang S, O'Brien MJ. The clinical significance of serrated polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:229-40; quiz 241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kalady MF. Sessile serrated polyps: an important route to colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1585-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer data in Australia. 2021. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/about. |

| 4. | Dierick NR, Nicholson BD, Fanshawe TR, Sundaralingam P, Kostalas SN. Serrated polyposis syndrome: defining the epidemiology and predicting the risk of dysplasia. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Herwaarden YJ, Pape S, Vink-Börger E, Dura P, Nagengast FM, Epping LSM, Bisseling TM, Nagtegaal ID. Reasons why the diagnosis of serrated polyposis syndrome is missed. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee J, Park SW, Kim YS, Lee KJ, Sung H, Song PH, Yoon WJ, Moon JS. Risk factors of missed colorectal lesions after colonoscopy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dekker E, Bleijenberg A, Balaguer F; Dutch-Spanish-British Serrated Polyposis Syndrome collaboration. Update on the World Health Organization Criteria for Diagnosis of Serrated Polyposis Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1520-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bleijenberg AG, IJspeert JE, van Herwaarden YJ, Carballal S, Pellisé M, Jung G, Bisseling TM, Nagtegaal ID, van Leerdam ME, van Lelyveld N, Bessa X, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Bastiaansen B, de Klaver W, Rivero L, Spaander MC, Koornstra JJ, Bujanda L, Balaguer F, Dekker E. Personalised surveillance for serrated polyposis syndrome: results from a prospective 5-year international cohort study. Gut. 2020;69:112-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | IJspeert JE, Rana SA, Atkinson NS, van Herwaarden YJ, Bastiaansen BA, van Leerdam ME, Sanduleanu S, Bisseling TM, Spaander MC, Clark SK, Meijer GA, van Lelyveld N, Koornstra JJ, Nagtegaal ID, East JE, Latchford A, Dekker E; Dutch workgroup serrated polyps & polyposis (WASP). Clinical risk factors of colorectal cancer in patients with serrated polyposis syndrome: a multicentre cohort analysis. Gut. 2017;66:278-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hazewinkel Y, Koornstra JJ, Boparai KS, van Os TA, Tytgat KM, Van Eeden S, Fockens P, Dekker E. Yield of screening colonoscopy in first-degree relatives of patients with serrated polyposis syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mankaney G, Rouphael C, Burke CA. Serrated Polyposis Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:777-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Herwaarden YJ, Verstegen MH, Dura P, Kievit W, Drenth JP, Dekker E, IJspeert JE, Hoogerbrugge N, Nagengast FM, Nagtegaal ID, Bisseling TM. Low prevalence of serrated polyposis syndrome in screening populations: a systematic review. Endoscopy. 2015;47:1043-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lockett MJ, Atkin WS. Hyperplastic polyposis (HPP): Prevalence and cancer risk. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:A742. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Hetzel JT, Huang CS, Coukos JA, Omstead K, Cerda SR, Yang S, O'Brien MJ, Farraye FA. Variation in the detection of serrated polyps in an average risk colorectal cancer screening cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2656-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kahi CJ, Hewett DG, Norton DL, Eckert GJ, Rex DK. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim HY. Serrated Polyposis Syndrome in a Single-Center 10-Year Experience. Balkan Med J. 2018;35:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Carballal S, Rodríguez-Alcalde D, Moreira L, Hernández L, Rodríguez L, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Gonzalo V, Bujanda L, Bessa X, Poves C, Cubiella J, Castro I, González M, Moya E, Oquiñena S, Clofent J, Quintero E, Esteban P, Piñol V, Fernández FJ, Jover R, Cid L, López-Cerón M, Cuatrecasas M, López-Vicente J, Leoz ML, Rivero-Sánchez L, Castells A, Pellisé M, Balaguer F; Gastrointestinal Oncology Group of the Spanish Gastroenterological Association. Colorectal cancer risk factors in patients with serrated polyposis syndrome: a large multicentre study. Gut. 2016;65:1829-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | IJspeert JEG, Bevan R, Senore C, Kaminski MF, Kuipers EJ, Mroz A, Bessa X, Cassoni P, Hassan C, Repici A, Balaguer F, Rees CJ, Dekker E. Detection rate of serrated polyps and serrated polyposis syndrome in colorectal cancer screening cohorts: a European overview. Gut. 2017;66:1225-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Win AK, Walters RJ, Buchanan DD, Jenkins MA, Sweet K, Frankel WL, de la Chapelle A, McKeone DM, Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Pearson SA, Pavluk E, Nagler B, Hopper JL, Gattas MR, Goldblatt J, George J, Suthers GK, Phillips KD, Woodall S, Arnold J, Tucker K, Field M, Greening S, Gallinger S, Aronson M, Perrier R, Woods MO, Green JS, Walker N, Rosty C, Parry S, Young JP. Cancer risks for relatives of patients with serrated polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:770-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Buchanan DD, Clendenning M, Zhuoer L, Stewart JR, Joseland S, Woodall S, Arnold J, Semotiuk K, Aronson M, Holter S, Gallinger S, Jenkins MA, Sweet K, Macrae FA, Winship IM, Parry S, Rosty C; Genetics of Colonic Polyposis Study. Lack of evidence for germline RNF43 mutations in patients with serrated polyposis syndrome from a large multinational study. Gut. 2017;66:1170-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bailie L, Loughrey MB, Coleman HG. Lifestyle Risk Factors for Serrated Colorectal Polyps: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:92-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Davenport JR, Su T, Zhao Z, Coleman HG, Smalley WE, Ness RM, Zheng W, Shrubsole MJ. Modifiable lifestyle factors associated with risk of sessile serrated polyps, conventional adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Gut. 2018;67:456-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | American Psychiatric Association; DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2013. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66101] [Cited by in RCA: 58227] [Article Influence: 3639.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 24. | Kosic A, Lindholm P, Järvholm K, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Axelsson E. Three decades of increase in health anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis of birth cohort changes in university student samples from 1985 to 2017. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;71:102208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lebel S, Mutsaers B, Tomei C, Leclair CS, Jones G, Petricone-Westwood D, Rutkowski N, Ta V, Trudel G, Laflamme SZ, Lavigne AA, Dinkel A. Health anxiety and illness-related fears across diverse chronic illnesses: A systematic review on conceptualization, measurement, prevalence, course, and correlates. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sunderland M, Newby JM, Andrews G. Health anxiety in Australia: prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service use. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tyrer P, Cooper S, Crawford M, Dupont S, Green J, Murphy D, Salkovskis P, Smith G, Wang D, Bhogal S, Keeling M, Loebenberg G, Seivewright R, Walker G, Cooper F, Evered R, Kings S, Kramo K, McNulty A, Nagar J, Reid S, Sanatinia R, Sinclair J, Trevor D, Watson C, Tyrer H. Prevalence of health anxiety problems in medical clinics. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:392-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Oxelmark L, Nordström G, Sjöqvist U, Löfberg R. Anxiety, functional health status, and coping ability in patients with ulcerative colitis who are undergoing colonoscopic surveillance. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:612-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Berian JR, Cuddy A, Francescatti AB, O'Dwyer L, Nancy You Y, Volk RJ, Chang GJ. A systematic review of patient perspectives on surveillance after colorectal cancer treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:542-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tarr GP, Crowley A, John R, Kok JB, Lee HN, Mustafa H, Sii KM, Smith R, Son SE, Weaver LJ, Cameron C, Dockerty JD, Schultz M, Murray IA. Do high risk patients alter their lifestyle to reduce risk of colorectal cancer? BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pilowsky I. Dimensions of hypochondriasis. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 623] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sirri L, Grandi S, Fava GA. The Illness Attitude Scales. A clinimetric index for assessing hypochondriacal fears and beliefs. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:337-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Alberts NM, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Jones SL, Sharpe D. The Short Health Anxiety Inventory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:68-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Andersson E, Andersson G, Lindefors N, Rück C, Axelsson E, Lekander M. Psychometric properties of Internet-administered measures of health anxiety: an investigation of the Health Anxiety Inventory, the Illness Attitude Scales, and the Whiteley Index. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HM, Clark DM. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:843-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 743] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:373-374. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Mykletun A, Heradstveit O, Eriksen K, Glozier N, Øverland S, Maeland JG, Wilhelmsen I. Health anxiety and disability pension award: The HUSK Study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Norbye AD, Abelsen B, Førde OH, Ringberg U. Health anxiety is an important driver of healthcare use. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Eilenberg T, Frostholm L, Schröder A, Jensen JS, Fink P. Long-term consequences of severe health anxiety on sick leave in treated and untreated patients: Analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;32:95-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Berge LI, Skogen JC, Sulo G, Igland J, Wilhelmsen I, Vollset SE, Tell GS, Knudsen AK. Health anxiety and risk of ischaemic heart disease: a prospective cohort study linking the Hordaland Health Study (HUSK) with the Cardiovascular Diseases in Norway (CVDNOR) project. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Erhart M, Wetzel RM, Krügel A, Ravens-Sieberer U. Effects of phone versus mail survey methods on the measurement of health-related quality of life and emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |