Published online Sep 24, 2024. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v15.i9.1245

Revised: July 25, 2024

Accepted: August 7, 2024

Published online: September 24, 2024

Processing time: 103 Days and 23.6 Hours

Facial teratoma is a rare benign tumor that accounts for about 1.6% of all tera

We present two cases of patients with abnormal fetal facial findings on US at se

Fetal maxillofacial teratomas can be diagnosed by US in early pregnancy, allo

Core Tip: Facial teratoma is a rare benign tumor that accounts for only about 1.6% of all teratomas and can be diagnosed by prenatal ultrasound (US). In this study, we presented two cases of pregnant women with prenatally diagnosed fetal maxillofacial teratomas by US. The study highlights the value of prenatal US in the identification of maxillofacial teratoma in early pregnancy and describes the ultrasonographic features of these tumors.

- Citation: Gao CF, Zhou P, Zhang C. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of fetal maxillofacial teratoma: Two case reports. World J Clin Oncol 2024; 15(9): 1245-1250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v15/i9/1245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v15.i9.1245

Teratomas are rare fetal and neonatal tumors composed of elements derived from the three germ layers. They typically develop in midline structures, the most common forms being ovarian (37%-43%), sacrococcygeal (28%-30%), testicular (10%-15%), and mediastinal (5%-6%)[1]. Head and neck teratomas account for approximately 5% of all teratomas, with an incidence of between 1/20000 and 1/40000 births. In contrast, the incidence of neonatal facial teratomas is less than 1:200000[2,3]. Although fetal facial teratomas are most likely to be histologically benign, there have been reports of invasive recurrence and malignant transformation following incomplete resection[3]. Additionally, maxillofacial tera

Prenatal ultrasound (US) screening has been reported to have extremely high sensitivity (100%) and a low false-po

Case 1: A 31-year-old female, gravida 3, para 1, miscarriage 1, presented to the US department at 16 weeks of gestation. US revealed a heterogeneous echogenicity on the fetal face.

Case 2: A 29-year-old female, gravida 1, para 0, presented to the US department at 16 weeks and 6 days of gestation. US revealed a cystic-solid echogenicity with irregular shape and uneven echo of the solid part.

Case 1: The patient had no complaints of fever, bleeding, or vaginal discharge.

Case 2: The patient had no subjective symptoms.

Case 1: The patient had no special medical history.

Case 2: The patient had no known past medical history.

Case 1: The patient had a miscarriage of a previous pregnancy, had no history of morphological abnormalities during delivery, and had no family history.

Case 2: The patient had no relevant personal or family history.

Case 1: The vital signs of the patient were stable. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurological examinations were nor

Case 2: The vital signs of the patient were stable and physical examination revealed no abnormal findings.

Case 1: Laboratory tests including total blood count, renal function, liver function, and other basic biochemical tests were normal.

Case 2: No obviously abnormal laboratory markers were observed.

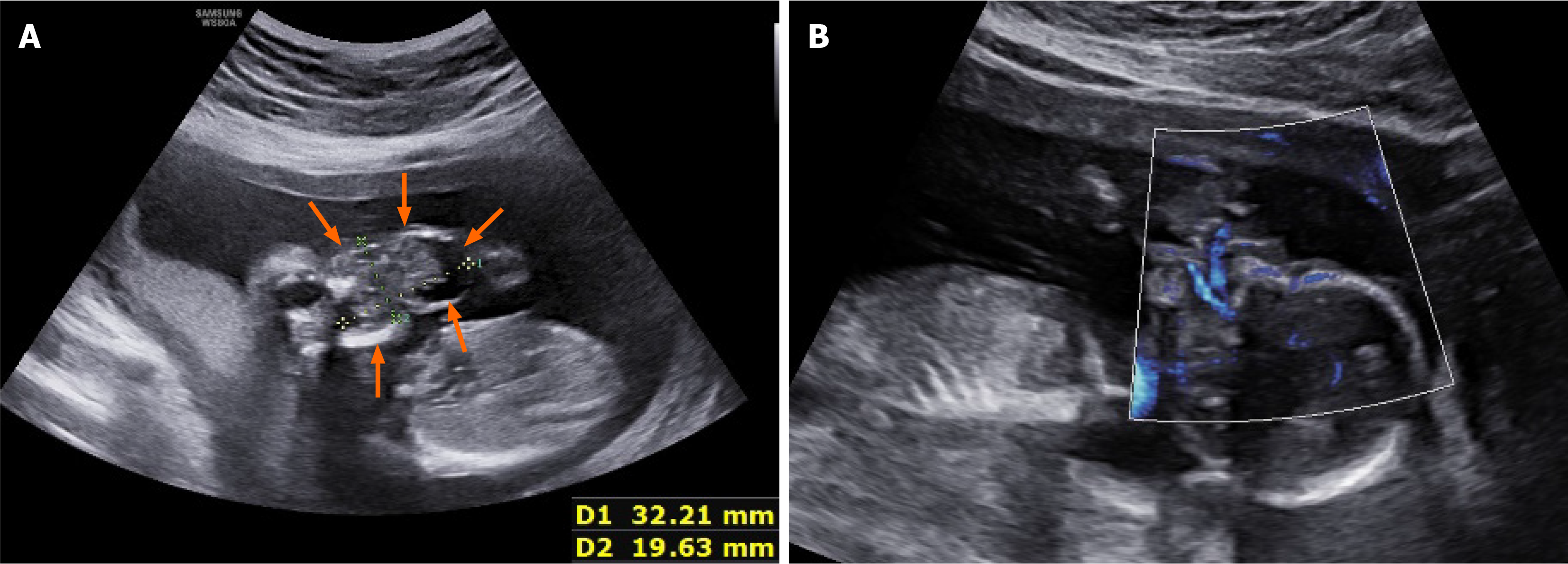

Case 1: US revealed a 32 mm × 20 mm × 31 mm heterogeneous echogenic mass on the fetus’s orofacial surface. Most of it was located outside the oral cavity, with roots filling the oral cavity and the fetus in a persistent open-mouth state (Figure 1). The mass was irregular in morphology, with heterogeneous and uneven internal echoes, predominantly solid ones; anechoic and strong echoes, but no obvious intracranial space-occupying lesions, were also seen. Microvascular flow imaging (MVFI) showed abundant blood flow signals, with blood supply originating from the deep part of the oral cavity. Three-dimensional US (3DUS) crystal imaging showed that the mass protruded from the face and was irregular in shape.

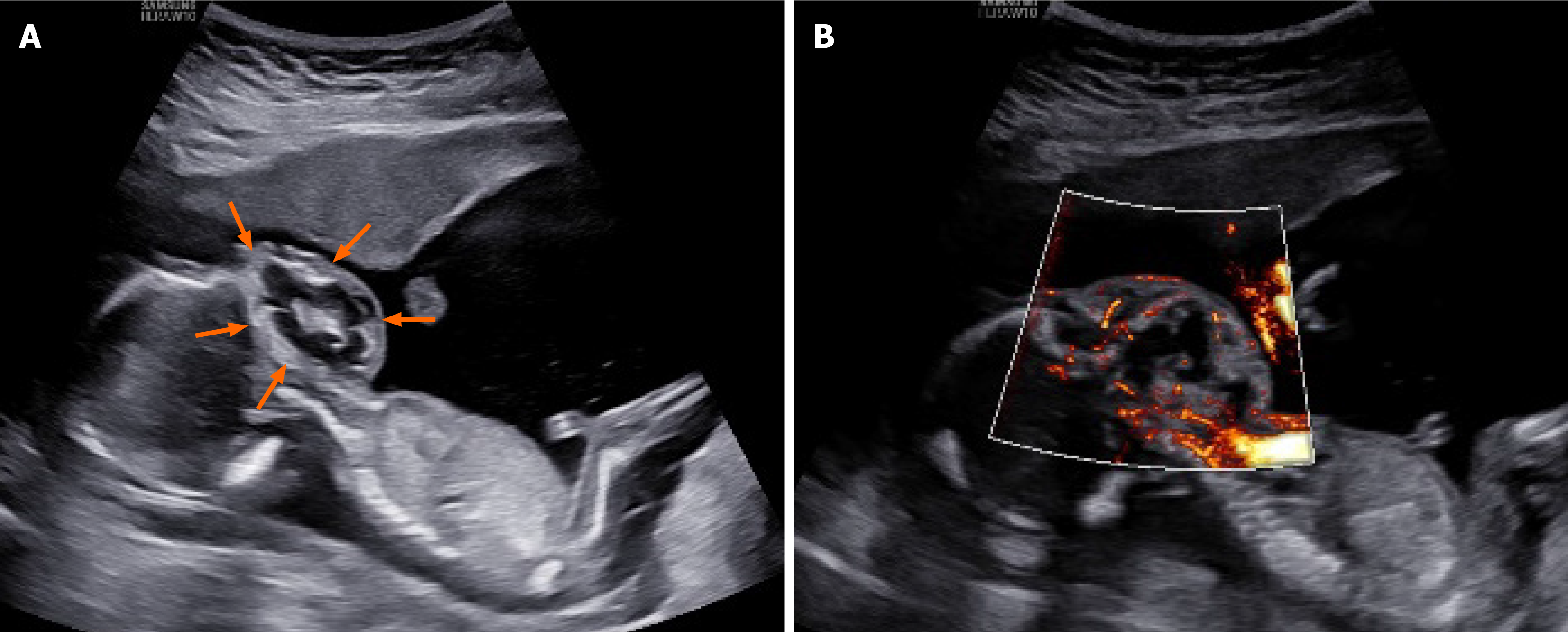

Case 2: US scanning of the fetal face and neck revealed a cystic-solid echogenic mass of 42 mm × 33 mm × 44 mm, mainly solid with irregular shape, with the solid part showing uneven low echo (Figure 2). MVFI showed rich blood flow signals within the mass. The upper edge of the mass reached the level of the palate and filled the oral cavity, while the lower edge reached the base of the neck. The lower, but not the upper, alveolus was visible, the mandible was deformed and flared, there was significant elevation of the bilateral facets, and the mass did not break through the skin. The nose and eye sockets were visible. 3DUS crystal imaging revealed the contours of the lesion in the coronal plane, markedly protruding up to the palate, down to the base of the neck, and on both sides of the cheeks.

The final diagnosis was maxillofacial teratoma, oral origin.

The final diagnosis was maxillofacial immature teratoma.

The patient decided to give up treatment and underwent labor induction after counseling.

The patient decided to give up treatment and underwent labor induction after counseling.

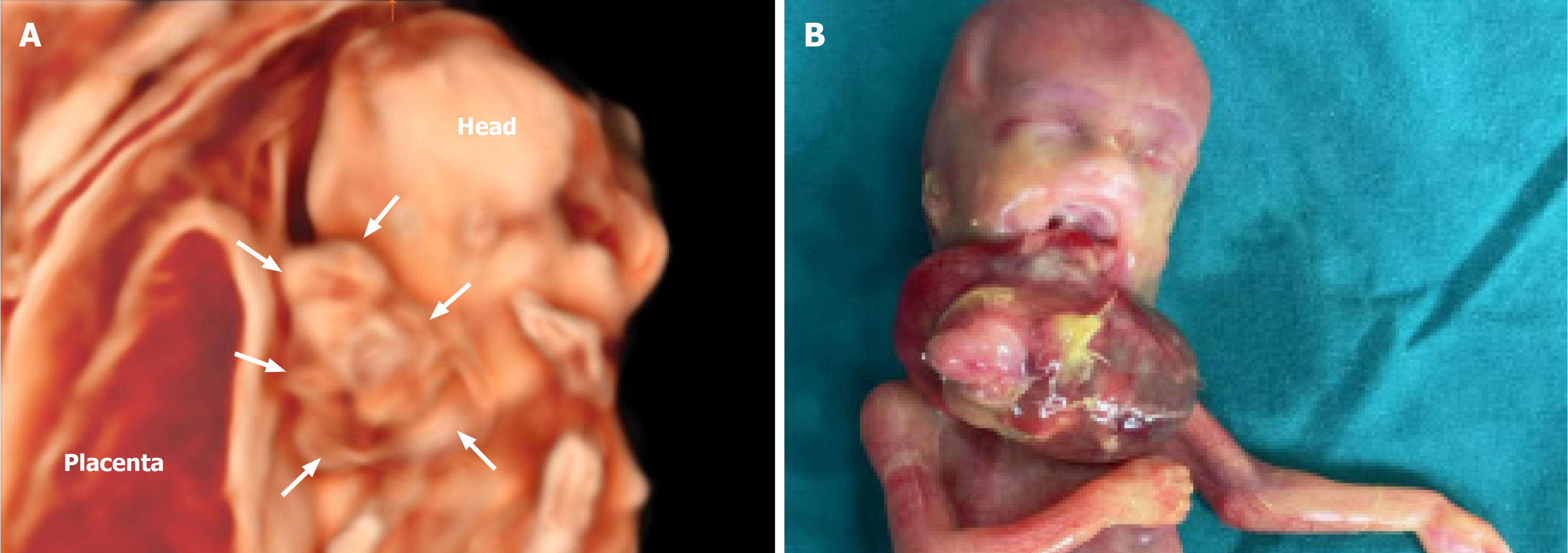

After induction of labor, the fetus showed a protuberant mass in the oral cavity that presented a translucent surface interconnecting the posterior palate and had a disorganized tissue structure (Figure 3). A biopsy of the lesion tissue was performed, and pathology revealed multiple tissue sources. Based on all the examinations, a diagnosis of maxillofacial teratoma (Pathological No. GX2205411) was confirmed.

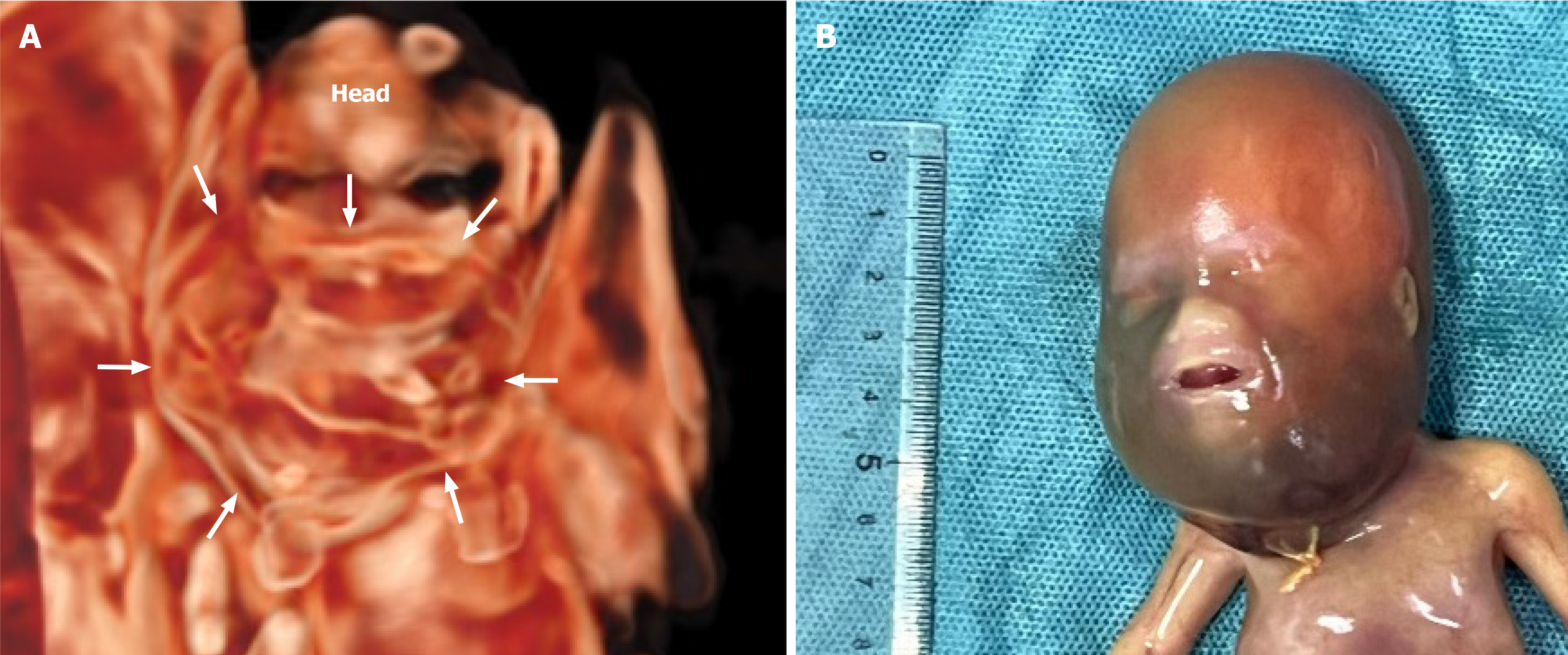

The postpartum gross appearance was darkly swollen from the maxillofacial region to the neck (Figure 4). A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and pathological results revealed a teratoma (Pathological No. 2214830).

US is the main diagnostic method for oropharyngeal and maxillofacial teratomas. The two cases herein reported were diagnosed by US at 16 weeks of gestation, which is earlier than the time of diagnosis reported in most cases[7,8]. Our study demonstrated the significance of US in the diagnosis of fetal maxillofacial teratoma, which is generally consistent with previous findings[4,9].

US imaging of case 1 showed mainly a cystic-solid echo with strong echogenic calcification visible in the solid part. MVFI showed abundant blood flow signals in the mass, which originated from the deep part of the oral cavity, and a strong, uninterrupted echo of the upper palate. Both conventional US and 3DUS showed that most of the mass protruded outside of the mouth. This finding was confirmed at postpartum gross examination, which showed a mass completely protruding from the upper palate, without cleft palate. The US images of case 2 also showed cystic-solid echo densities but without typical calcification signs. Blood flow signal was visible in the solid part, and the mass was in a deep posi

After consultation, both mothers and their families finally chose to induce labor due to poor prognosis. However, since they did not agree to autopsy, the exact origin of the teratomas could not be determined. Management of fetal oral and maxillofacial teratomas is challenging. Perinatal management includes ex-utero intrapartum treatment initiated by intubation during delivery or surgery on placental support to remove the tumor during cesarean section and before cutting the umbilical cord[12,13]. It has been reported that oropharyngeal teratomas have been successfully removed under fetoscopy, and that early surgery can avoid facial structure distortion and airway obstruction caused by further expansion of the mass[14]. However, fetal maxillofacial teratomas are also associated with congenital heart disease, cleft lip and palate, hypoplasia of the mandible, and other congenital malformations[15,16]. Therefore, in consideration of future development of the fetuses, the patients decided to give up treatment.

Fetal maxillofacial teratomas can be diagnosed by US in early pregnancy, allowing parents to expedite treatment deci

| 1. | Paran TS, Coyle D. Teratomas (All Locations). Pediatric Surg. 2021;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | El Ezzi O, Gengler C, de Buys Roessingh A. Cystic teratoma of the head: Diagnosis pitfalls. Oral Maxil Surg Cases. 2020;6:100135. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hodges MM, Crombleholme TM, Marwan AI, Mirsky D, Meyers M, Behrendt N, French B, Kelley P, Liechty KW. Massive facial teratoma managed with the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure and use of a 3-dimensional printed model for planning of staged debulking. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2017;17:15-19. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Narayan R, Ahmad MS Sr, Kumar A. Fetal Oropharyngeal Teratoma: Prenatal Diagnosis and Imaging Characteristics. Cureus. 2020;12:e11329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kekre G, Gupta A, Kothari P, Dikshit V, Patil P, Deshmukh S, Kulkarni A, Deshpande A. Congenital facial teratoma in a neonate: Surgical management and outcome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2016;6:141-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arisoy R, Erdogdu E, Kumru P, Demirci O, Ergin N, Pekin O, Sahinoglu Z, Tugrul AS, Sancak S, Çetiner H, Celayir A. Prenatal diagnosis and outcomes of fetal teratomas. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44:118-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Santana EF, Helfer TM, Piassi Passos J, Araujo Júnior E. Prenatal diagnosis of a giant epignathus teratoma in the third trimester of pregnancy using three-dimensional ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Case report. Med Ultrason. 2014;16:168-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yan C, Shentu W, Gu C, Cao Y, Chen Y, Li X, Wang H. Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Oral Masses by Ultrasound Combined With Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41:597-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li YL, Zhen L, Li DZ. Prenatal Diagnosis of Oral Teratoma by Ultrasound. J Med Ultrasound. 2024;32:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malho AS, Ximenes R, Ferri A, Bravo-Valenzuela NJ, Araujo Júnior E. MV-Flow and LumiFlow: new Doppler tools for the visualization of fetal blood vessels. Radiol Bras. 2021;54:277-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bois E, Thierry B. Life-Threatening Oropharyngeal Teratoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165:232-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bence CM, Wagner AJ. Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedures. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Skarsgard ED, Chitkara U, Krane EJ, Riley ET, Halamek LP, Dedo HH. The OOPS procedure (operation on placental support): in utero airway management of the fetus with prenatally diagnosed tracheal obstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:826-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kontopoulos EV, Gualtieri M, Quintero RA. Successful in utero treatment of an oral teratoma via operative fetoscopy: case report and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:e12-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anderson PJ, David DJ. Teratomas of the head and neck region. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:369-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Singhal R, Garg VK, Ratre BK, Deganwa M. Oral teratoma in a neonate: A case report of anesthetic challenge. Saudi J Anaesth. 2020;14:520-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |