Published online Aug 24, 2024. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v15.i8.1102

Revised: May 15, 2024

Accepted: June 13, 2024

Published online: August 24, 2024

Processing time: 197 Days and 20.8 Hours

Primary vaginal cancer is rare and most vaginal tumors are metastatic, often arising from adjacent gynecologic structures. Primary vaginal cancers are also more common among postmenopausal women and most of these are squamous cell carcinomas, with adenocarcinomas being relatively rare. Vaginal bleeding is the most common clinical manifestation of vaginal adenocarcinoma. About 70% of vaginal adenocarcinomas are stage I lesions at the time of diagnosis, for which radical surgery is recommended. However, more advanced vaginal cancers are not amenable to radical surgical treatment and have poor clinical outcomes. Optimal treatments modes are still being explored. Here, we report a rare case of stage IIb primary vaginal adenocarcinoma for which an individually designed vaginal applicator for after-loading radiotherapy was used to achieve good tumor control.

A 62-year-old woman presented to our clinic after 3 months of abnormal postme

Primary vaginal adenocarcinoma is rare, and prognosis is poor in most vaginal cancers of locally advanced stages, which cannot be treated with radical surgery. Better tumor control can be achieved with an individualized vaginal applicator that allows administration of a higher radical dose to the tumor area while protecting normal tissues.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of stage IIb primary vaginal adenocarcinoma. After three cycles of induction chemotherapy and intensity-modulated external radiation therapy, an individually designed vaginal applicator for after-loading radiotherapy was used to achieve good tumor control.

- Citation: Saijilafu, Gu YJ, Huang AW, Xu CF, Qian LW. Individualized vaginal applicator for stage IIb primary vaginal adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2024; 15(8): 1102-1109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v15/i8/1102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v15.i8.1102

Vaginal cancer is relatively uncommon, comprising 7% of all gynecologic cancers in women[1]. Among these, primary vaginal cancer is rare, accounting for 10% of all vaginal malignancies[2]. Vaginal cancer is a histologic diagnosis based on a positive vaginal biopsy and no past history of gynecologic malignancy. Most vaginal tumors (83.4%) are squamous cell carcinomas, followed by adenocarcinomas[3]. Vaginal adenocarcinoma may originate from vaginal adenopathy, residual mesonephric ducts, periurethral glands, or endometriotic foci. Most adenocarcinomas with clear cell histology in young women exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero have a good prognosis[4]. In contrast, non-DES-associated vaginal cancers, which usually occur in older women, are more aggressive and have high recurrence rates[5].

A 62-year-old woman presented with irregular postmenopausal vaginal bleeding for more than 3 months.

The patient had a history of regular menstruation, menopause at age 50 years, no post-menopausal vaginal bleeding with contact, and no abnormal vaginal discharge. For more than 3 months prior to being seen clinically, there were no obvious causative factors; during this time, she experienced small amounts of irregular, bright red vaginal bleeding, which gradually increased.

Hypertension for 8 years, currently taking one nifedipine tablet daily with good blood pressure control. Eight years ago, she had a cerebral infarction, with no residual sequelae.

First menstruation at age 13 years, menopause at age 50 years, previous regular menstruation, two healthy children; denied family history of genetic disorders.

Age-related vulvar changes; multiple nodular-like projections on the anterior wall of the vagina, fused into patches; a lesion involved the vaginal fornix to the vaginal opening; no obvious abnormality palpated on the posterior wall; cervix was unable to be exposed; cervix and parametrium were soft on palpation; no difference between the uterus and double adnexa.

Tumor marker glycan chain antigen CA15-3: 27.51 U/mL (reference < 25 U/mL); other tumor markers CA19-9, CA125, squamous cell carcinoma, and alpha-fetoprotein all within normal range. Blood routine, liver, and kidney functions normal.

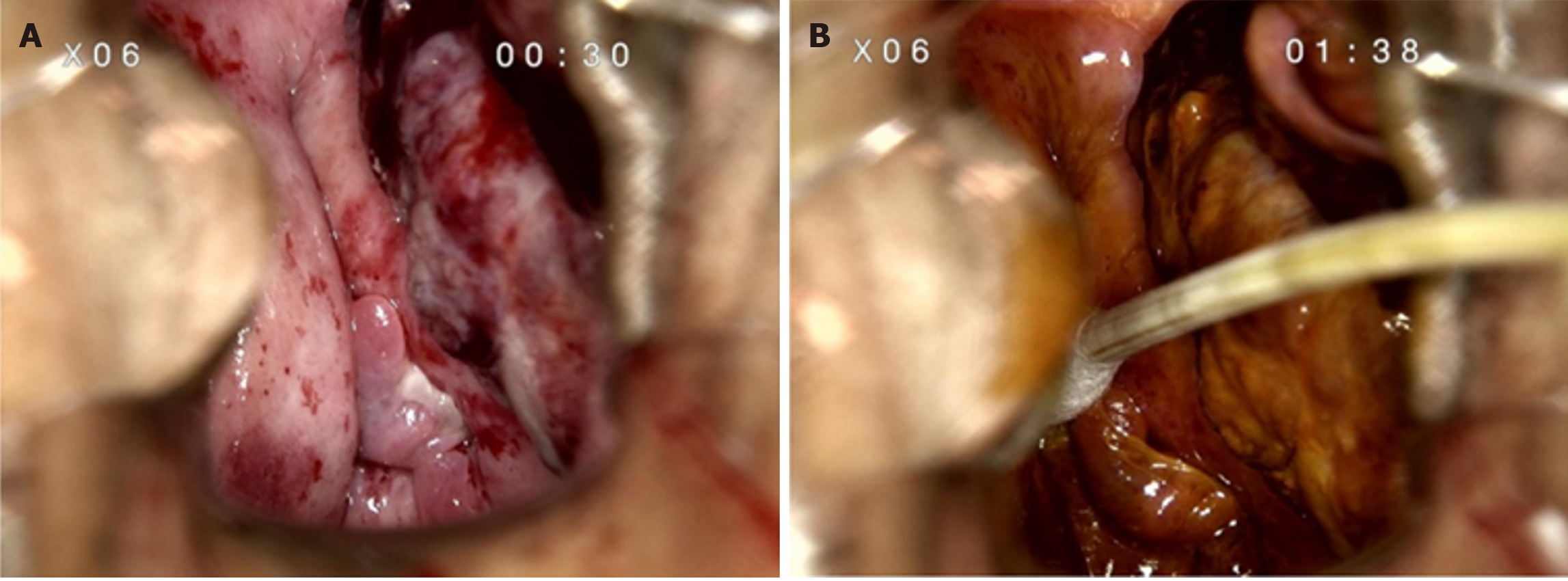

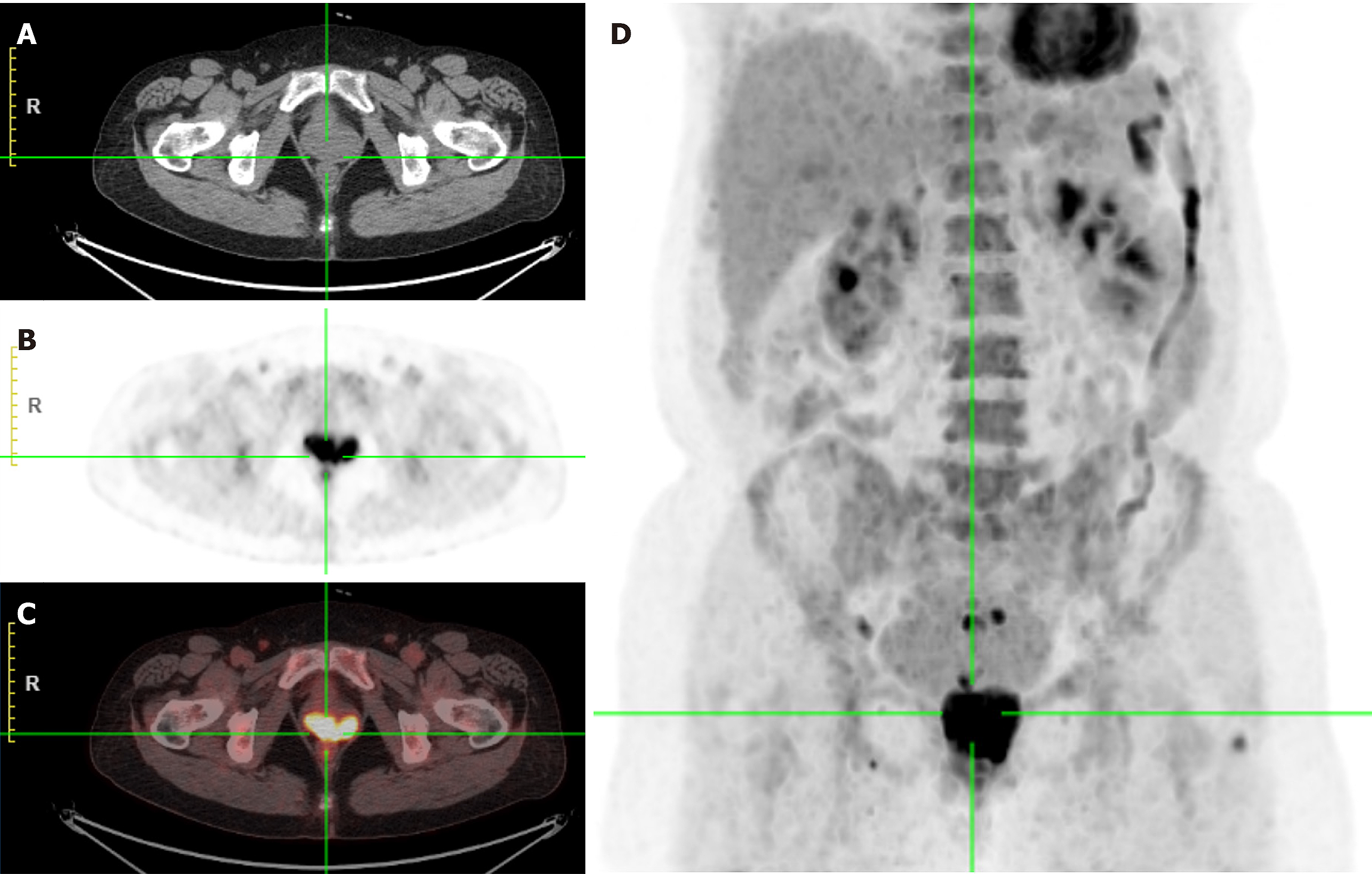

Colposcopy showed a mass in the left anterior vaginal wall involving the left fornix to the vaginal opening, measuring 4 cm × 5.0 cm (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scan showed a vaginal soft tissue mass with increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose metabolism, indicating the first consideration of malignancy (Figure 2). Pelvic enhanced CT showed occupation of the left and anterior vaginal walls (Figure 3A).

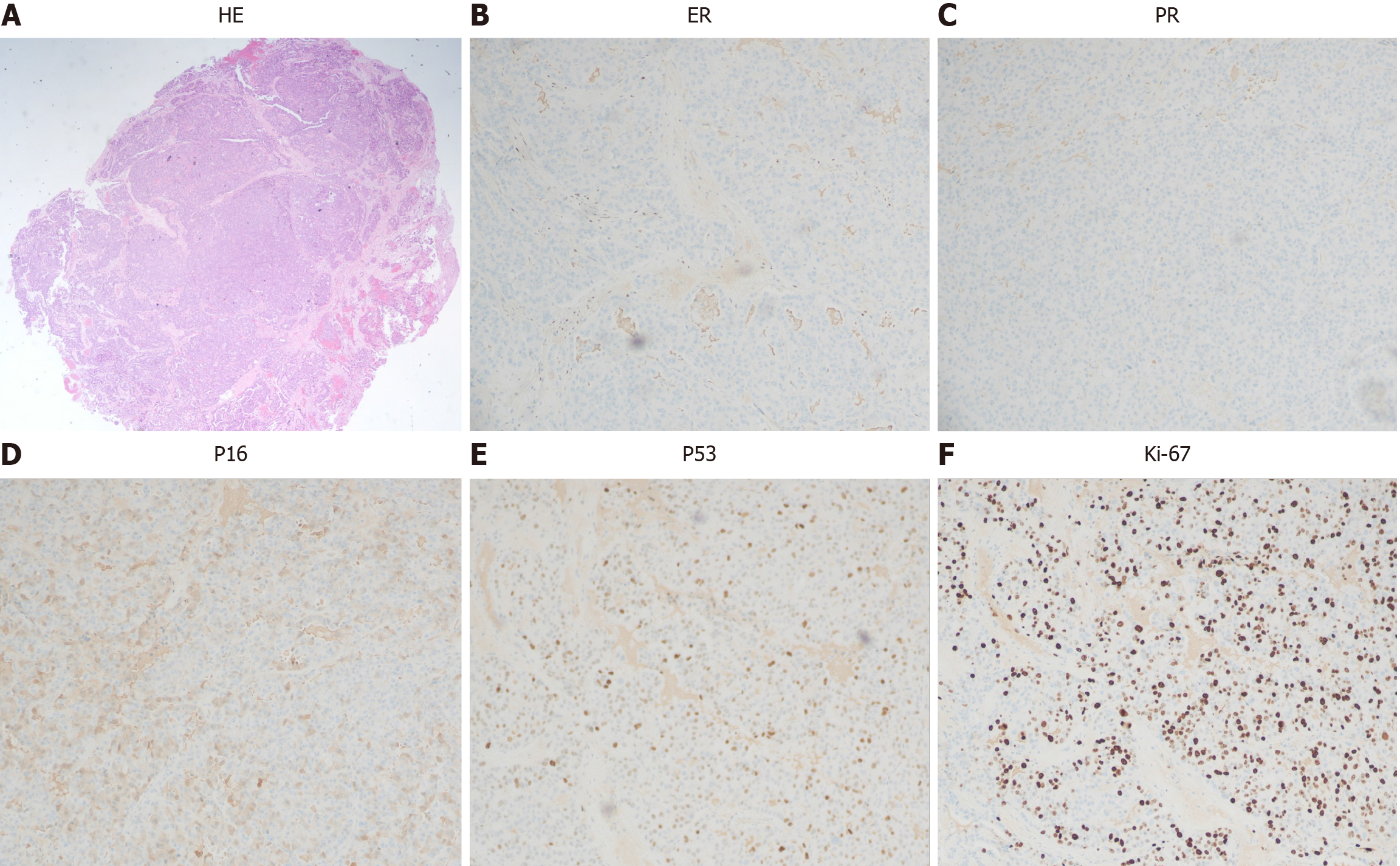

Pathologic biopsy under colposcopy showed adenocarcinoma of the anterior vaginal wall. Immunohistochemistry showed estrogen receptor (+ 5%), progesterone receptor (−), P16 (some weak +), P53 (patchy +), and Ki-67 (70%, 100 ×) (Figure 4).

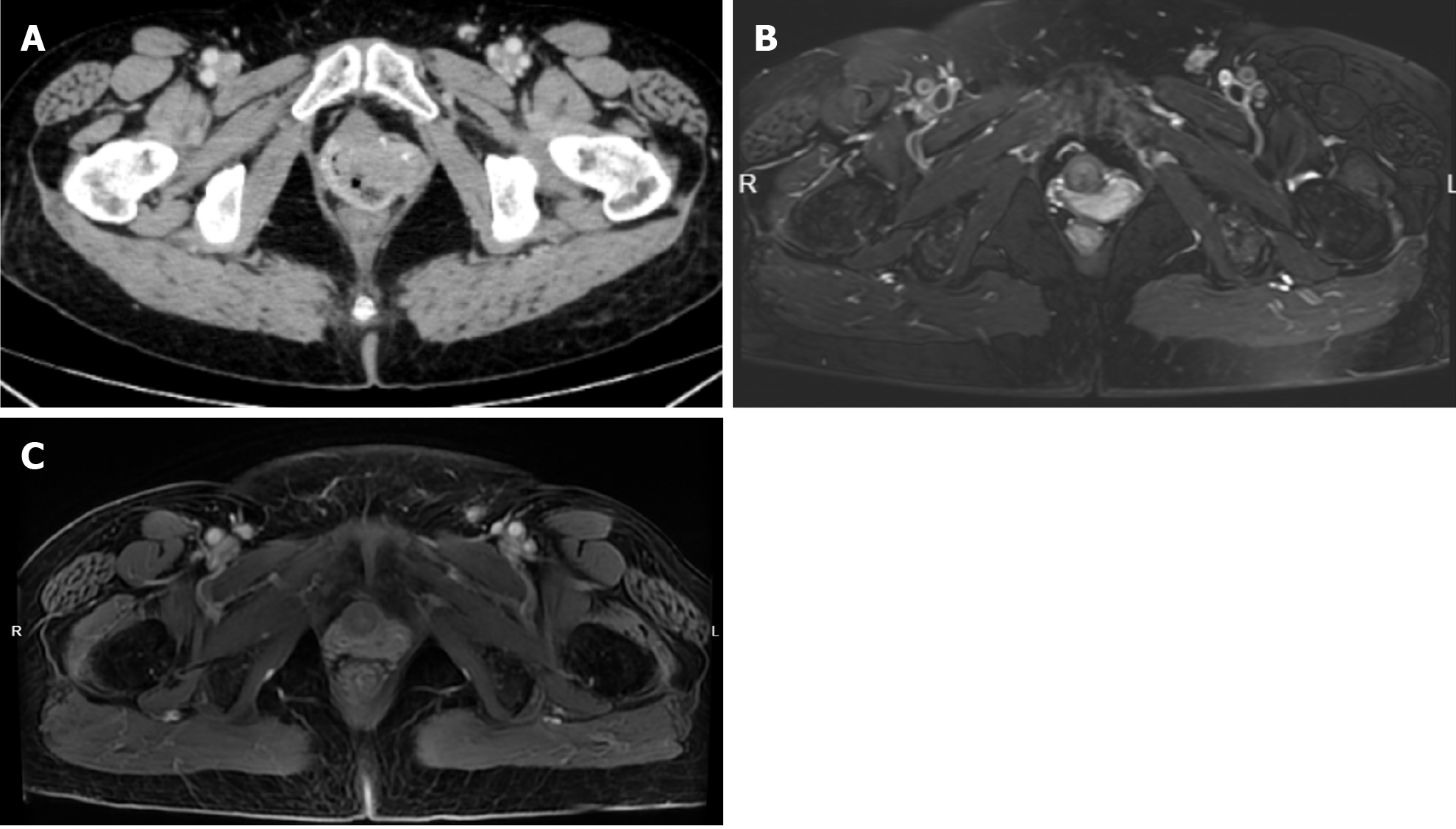

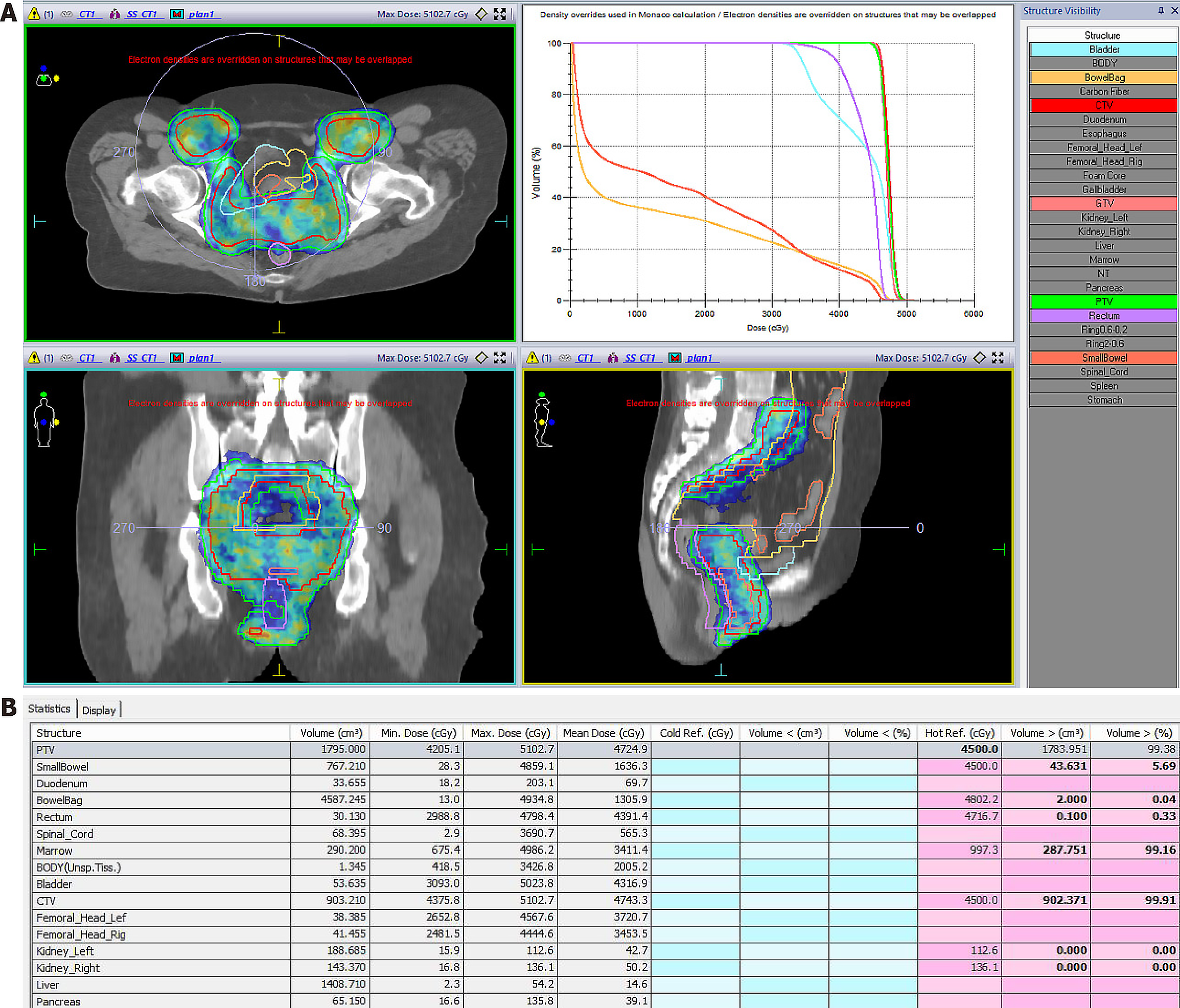

The patient was diagnosed with stage IIb vaginal cancer and administered three cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel, after which pelvic enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed partial lesion remission (Figure 3B). The patient then underwent intensity-modulated external radiation therapy, which was prescribed at 45 gray (gy) in 25 fractions within 5 weeks, with clinical targets including the vagina, cervix, paracervix, part of the uterus, and high-risk lymph node drainage areas (Figure 5). Simultaneous chemotherapy, carboplatin weekly regimen, was administered concurrent with external irradiation, for a total of five cycles, after which the vaginal lesion was further reduced (Figure 3C).

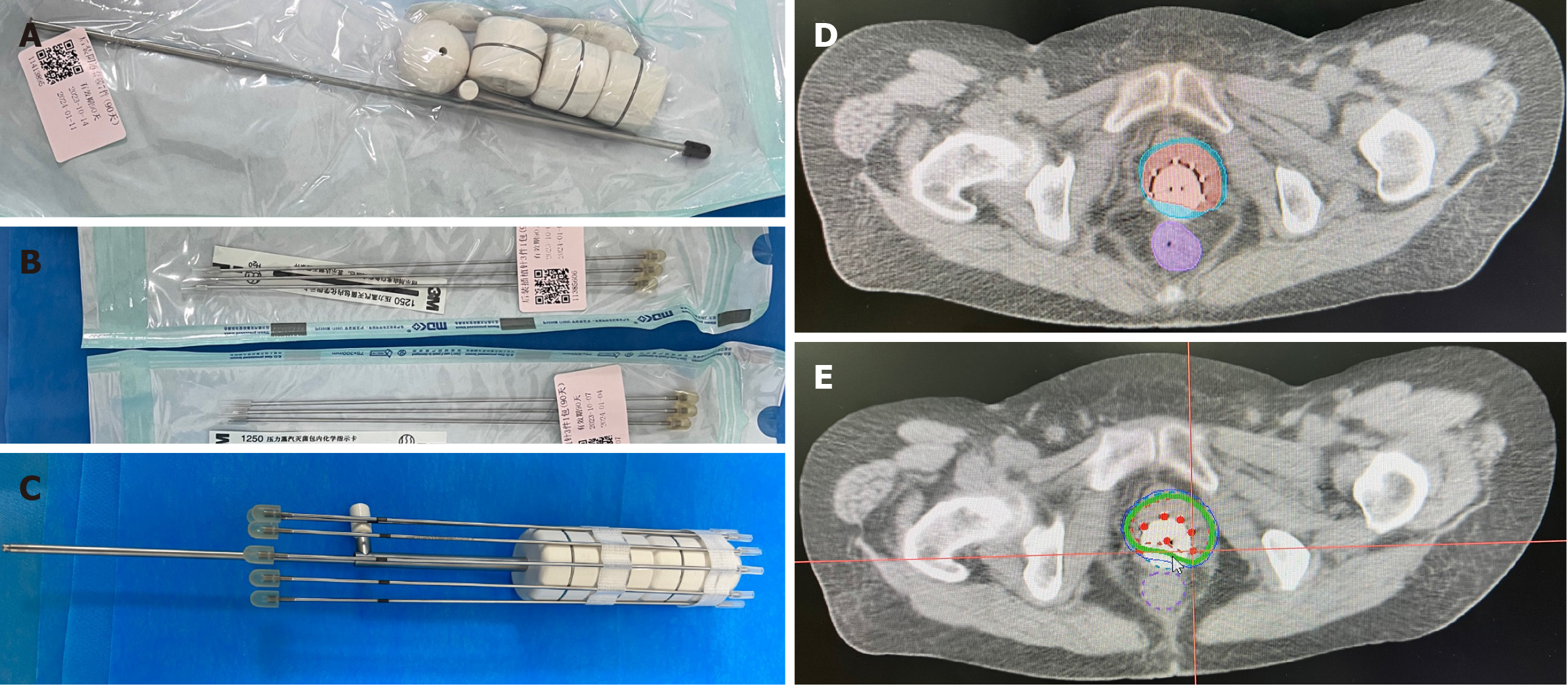

Subsequently, based on the residual lesion morphology, we designed an individualized after-loading brachytherapy applicator. This consisted of a commercially available cylindrical vaginal applicator (Figure 6A) and six interstitial needles (Figure 6B). The assembled applicator (Figure 6C) was covered with a condom, then sterilized with a povidone-iodine wipe. The device was implanted into the vagina, then adjusted so that the implantation needles were distributed over the lesion. The high-risk clinical target volume is shown in Figure 6D. The after-loading brachytherapy dose received by this patient was 30 gy in five fractions (Figure 6E).

After radical radiotherapy, the patient entered the outpatient follow-up phase. Three months later, enhanced MRI suggested a slight thickening of the anterior vaginal wall with mild enhancement.

Primary vaginal adenocarcinomas are very rare, with generally poor prognosis, possibly due to the scarce information about these and other rare tumors available to healthcare policymakers and stakeholders[6]. Rare cancers pose challenges for diagnosis, treatment, and clinical decision-making. There have been no randomized clinical trials defining treatment for vaginal cancer, given its rarity. Instead, treatment approaches are extrapolated from cervical and anal cancers.

The most important prognostic factor for vaginal cancer is the stage at diagnosis[2], because most patients with stage I are candidates for radical surgical excision. Other factors that negatively affect prognosis include tumor size > 4 cm, older age, and possible location of the tumor outside the upper third of the vagina[7]. This may be because patients with these high-risk factors are often unable to undergo surgery. In general, adenocarcinoma has a worse prognosis than does squamous cell carcinoma, higher distant metastasis rate, and more radiotherapy resistance[8].

Patients with more advanced disease, radiotherapy (with intracavitary or interstitial therapy, depending on tumor thickness) is a reasonable option[8,9]. However, treatment must be individualized according to the tumor site and size at presentation and response to initial external-beam radiation therapy[10]. Because of the poor prognosis with radiation alone, we often proceed with the combined use of radiation and concurrent chemotherapy in women with tumor size > 4 cm[11,12]. Neoadjuvant therapy is a promising alternative treatment for patients with stages II–IV[13]. Neoadjuvant therapy showed a high clinical response rate in a small prospective study[14] and may help reduce the irradiated volume of external radiotherapy and mitigate side effects, while providing high tumor coverage with subsequent after-loading brachytherapy.

Brachytherapy improves survival in primary vaginal cancer, and tumors > 5 cm show the most significant responses to this approach[15]. Its steep dose gradient enables delivery of high radiation doses to the primary tumor, while simulta

Three-dimensional image-guided high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy improves patient survival[19]. However, complications from this invasive operation can include hemorrhage, vaginal fistula, and intestinal perforation. Sometimes, commercially available applicators cannot be used because of anatomical barriers or tumor size or topography that disallow adequate target volume coverage. Over the last decade, 3D printing has been increasingly used to manufacture customized brachytherapy applicators, with gynecological tumors being the most common indication[20]. However, 3D printing is expensive, time consuming, and of limited clinical accessibility. The applicator used herein combined a commercially available cylindrical vaginal applicator with interstitial needles, offering the advantages of high dose conformity, non-invasiveness, and reproducibility. This case provides reference values for future use in similar clinical contexts.

While very rare, primary vaginal adenocarcinoma, like most locally advanced inoperable vaginal cancers, has a poor prognosis. The patient presented herein was first treated with three cycles of induction chemotherapy, followed by concurrent chemo-radiotherapy. In the after-loading brachytherapy phase, an individually designed source applicator was used to ensure high-dose tumor delivery, while protecting normal organs. This treatment method achieved good results.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 9919] [Article Influence: 4959.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Jhingran A. Updates in the treatment of vaginal cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:344-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rajaram S, Maheshwari A, Srivastava A. Staging for vaginal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:822-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huo D, Anderson D, Palmer JR, Herbst AL. Incidence rates and risks of diethylstilbestrol-related clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix: Update after 40-year follow-up. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Frank SJ, Deavers MT, Jhingran A, Bodurka DC, Eifel PJ. Primary adenocarcinoma of the vagina not associated with diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:470-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L, Mallone S, De Angelis R, Ardanaz E, Comber H, Dimitrova N, Leinonen MK, Siesling S, van der Zwan JM, Van Eycken L, Visser O, Žakelj MP, Anderson LA, Bella F, Kaire I, Otter R, Stiller CA, Trama A; RARECAREnet working group. Burden and centralised treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1022-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 41.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hiniker SM, Roux A, Murphy JD, Harris JP, Tran PT, Kapp DS, Kidd EA. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina: prognostic factors, treatment patterns, and outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131:380-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frank SJ, Jhingran A, Levenback C, Eifel PJ. Definitive radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:138-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tewari KS, Cappuccini F, Puthawala AA, Kuo JV, Burger RA, Monk BJ, Manetta A, Berman ML, Disaia PJ, Nisar AM. Primary invasive carcinoma of the vagina: treatment with interstitial brachytherapy. Cancer. 2001;91:758-770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Lian J, Dundas G, Carlone M, Ghosh S, Pearcey R. Twenty-year review of radiotherapy for vaginal cancer: an institutional experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:298-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dalrymple JL, Russell AH, Lee SW, Scudder SA, Leiserowitz GS, Kinney WK, Smith LH. Chemoradiation for primary invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Samant R, Lau B, E C, Le T, Tam T. Primary vaginal cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiation using Cis-platinum. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:746-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Di Donato V, Bellati F, Fischetti M, Plotti F, Perniola G, Panici PB. Vaginal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;81:286-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Benedetti Panici P, Bellati F, Plotti F, Di Donato V, Antonilli M, Perniola G, Manci N, Muzii L, Angioli R. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery in patients affected by vaginal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Orton A, Boothe D, Williams N, Buchmiller T, Huang YJ, Suneja G, Poppe M, Gaffney D. Brachytherapy improves survival in primary vaginal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chargari C, Deutsch E, Blanchard P, Gouy S, Martelli H, Guérin F, Dumas I, Bossi A, Morice P, Viswanathan AN, Haie-Meder C. Brachytherapy: An overview for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:386-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Westerveld H, Nesvacil N, Fokdal L, Chargari C, Schmid MP, Milosevic M, Mahantshetty UM, Nout RA. Definitive radiotherapy with image-guided adaptive brachytherapy for primary vaginal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e157-e167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gadducci A, Fabrini MG, Lanfredini N, Sergiampietri C. Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina: natural history, treatment modalities and prognostic factors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;93:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Goodman CD, Mendez LC, Velker V, Weiss Y, Leung E, Louie AV, Warner A, Hajdok G, D'Souza DP. 3D image-guided interstitial brachytherapy for primary vaginal cancer: A multi-institutional experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Segedin B, Kobav M, Zobec Logar HB. The Use of 3D Printing Technology in Gynaecological Brachytherapy-A Narrative Review. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |