Published online Jul 24, 2024. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v15.i7.908

Revised: May 22, 2024

Accepted: June 11, 2024

Published online: July 24, 2024

Processing time: 133 Days and 7 Hours

Psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain species of mushrooms, is known for its effects on anxiety and depression. It has recently gained increasing interest for its potential therapeutic effects, particularly in patients with advanced cancer. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to evaluate the effects of psilocybin on adult patients with advanced cancer.

To investigate the therapeutic effect of psilocybin in patients with advanced cancer.

A comprehensive search of electronic databases was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Google Scholar for articles published up to February 2023. The reference lists of the included studies were also searched to retrieve possible additional studies.

A total of 7 studies met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review, comprising 132 participants. The results revealed significant improvements in quality of life, pain control, and anxiety relief following psilocybin-assisted therapy, specifically results on anxiety relief. Pooled effect sizes indicated statistically significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety at both 4 to 4.5 months [35.15 (95%CI: 32.28-38.01)] and 6 to 6.5 months [33.06 (95%CI: 28.73-37.40)]. Post-administration compared to baseline assessments (P < 0.05). Additionally, patients reported sustained improvements in psychological well-being and existential distress fo

The findings provided compelling evidence for the potential benefits of psilocybin-assisted therapy in improving quality of life, pain control, and anxiety relief in patients with advanced cancer.

Core Tip: Psilocybin-assisted therapy shows promising results in improving quality of life, pain control, and anxiety relief for patients with advanced cancer. This systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies involving 132 participants demon

- Citation: Bader H, Farraj H, Maghnam J, Abu Omar Y. Investigating the therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin in advanced cancer patients: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Oncol 2024; 15(7): 908-919

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v15/i7/908.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v15.i7.908

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in exploring alternative therapeutic approaches to address the complex physical, psychological, and existential distress experienced by patients with advanced cancers (Mok et al[1], 2010; Henoch and Danielson[2], 2009). Among these approaches, the use of psychedelics, particularly psilocybin, has gained considerable attention for its potential to alleviate symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and existential distress, while also facilitating profound spiritual experiences and promoting existential well-being (Schimmers et al[3], 2022). Advanced cancer presents a myriad of challenges for patients and healthcare providers alike. The progression of the disease is often accompanied by a spectrum of physical symptoms, including pain, nausea, fatigue, and shortness of breath, which can significantly impact patients' quality of life and functional status (Paice and Ferrell[4], 2011; Gupta et al[5], 2007). Moreover, the psychological burden of living with advanced cancer is substantial, with many patients experiencing heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and existential distress as they confront the uncertainties of their prognosis and the existential implications of their illness (Vehling and Kissane[6], 2018 and Greer et al[7], 2020).

Conventional treatment approaches for advanced cancer typically involve a combination of modalities such as ra

In recent years, however, there has been a remarkable shift in attitudes toward psychedelics, fueled in part by a re-evaluation of their therapeutic potential and a burgeoning body of scientific evidence supporting their safety and efficacy (Sessa[12], 2014). Advances in neuroimaging technology and psychopharmacology have shed new light on the mechanisms of action underlying psychedelic-induced alterations in consciousness, revealing their profound effects on brain function, cognition, and emotion regulation (Moujaes et al[13], 2023). Central to this resurgence has been the concept of psychedelic-assisted therapy, which combines the administration of a psychedelic substance with psychotherapeutic support to facilitate profound psychological insights, emotional processing, and therapeutic breakthroughs. Emerging research suggests that psychedelic-assisted therapy holds promise for a wide range of mental health conditions, including treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and illicit substance use disorders (Reiff et al[14], 2020; Schenberg[15], 2018).

In the field of oncology, the potential utility of psychedelics therapy is particularly compelling, given the profound psychological and existential distress experienced by patients with advanced cancer. By facilitating transformative experiences, enhancing existential coping mechanisms, and promoting spiritual well-being, psychedelic therapy has the potential to complement existing cancer treatments and improve the overall quality of life for patients facing life-threatening illnesses. Psilocybin, a psychedelic chemical that’s naturally found in certain species of mushrooms, has emerged as a focal point of interest in the context of advanced cancer care due to its unique pharmacological properties and demonstrated therapeutic potential (Grob et al[16], 2011; Griffiths et al[17], 2016). Unlike traditional pharmacotherapies, which primarily target symptoms through direct modulation of neurotransmitter systems, psilocybin acts as a serotonin receptor agonist, particularly at the 5-HT2A receptor, leading to profound alterations in consciousness, perception, and self-awareness (Rahbarnia et al[18], 2023 and Carter et al[19], 2005).

Research into the effects of psilocybin has shown therapeutic potential for a different range of psychiatric and existential conditions, including depression, anxiety, addiction, and existential distress. In the context of advanced cancer care, where patients grapple with the existential realities of mortality, identity, and meaning, psilocybin therapy offers a novel approach to addressing the multidimensional needs of this population. Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses have mainly focused on the broader application of psychedelics in psychiatric disorders, such as depression and PTSD, rather than specifically examining the effects of psilocybin in patients with advanced cancer This emphasis gains significance given the progressive strides in cancer therapy and the emergence of novel medications, which have not been paralleled by commensurate investigations into interventions aimed at enhancing the quality of life for individuals grappling with advanced cancer. As a result, there is a true need for a thorough synthesis of the available evidence to clarify the effects of psilocybin on psychological outcomes, existential well-being, and quality of life in this vulnerable patient population. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to address this research gap by critically evaluating the existing literature on the use of psilocybin.

What is the impact of psilocybin therapy on psychological distress, existential concerns, and quality of life in adult patients with advanced cancer?

This systematic review and meta-analysis are reported following guidelines outlined in Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al[20], 2021).

A comprehensive systematic search of the literature was carried out, encompassing articles released until February 1st, 2023. Primary databases including PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Google Scholar were systematically explored using specific topic-related keywords to construct search queries. Following this, identified studies underwent a rigorous selection process.

In formulating the search strategy for PubMed, a blend of free keyword searches and controlled MeSH terms was utilized to ensure comprehensive coverage. Keyword searches were tailored to scrutinize the entirety of the text, augmenting the sensitivity of the search strategy. For CENTRAL, slight modifications were made to adapt the PubMed strategy accordingly. Table 1 illustrates the assortment of keywords employed for each search, delineating the approach for comprehensive literature retrieval.

| Database | Search field | Search string |

| PubMed | Title, abstract | (psilocybin OR psilocybine OR hallucinogens OR serotonin agonists OR mushroom poisoning) AND (neoplasms OR cancer OR oncology OR neoplasm metastasis OR neoplasm staging OR neoplasm recurrence, local OR disease progression OR palliative care OR terminal care OR hospice care OR terminal illness OR quality of life) |

| CENTRAL | All fields | (psilocybin OR magic mushrooms) AND (cancer OR oncology) AND (advanced OR metastatic) |

In addition to searching the specified databases, a direct inquiry was conducted using the Google Scholar database. To ensure the retrieval of the most relevant outcomes within the initial pages, the exploration integrated precise terms associated with the topic "psilocybin in patients with advanced cancer", encompassing a range of keywords including Psilocybin, Psilocybine, Hallucinogens, Serotonin agonists, Mushroom poisoning, Neoplasms, Cancer, Oncology, Neoplasm metastasis, Neoplasm staging, Neoplasm recurrence (local), Disease progression, Palliative care, Terminal care, Hospice care, Terminal illness, Quality of life, Symptom assessment, Symptom management and Psychological adap

The research question for this study was developed from the Population Intervention Comparison Outcomes Study Design (PICOS) framework. The PICOS criteria for eligible studies were defined as follows:

Population (P): Adults diagnosed with advanced cancer.

Intervention (I): Administration of psilocybin or psilocybin-containing substances.

Comparison (C): Not applicable (as this review primarily focuses on single-arm studies)

Outcomes (O): Reporting outcomes related to quality of life, pain control, or anxiety relief.

Study design (S): Including randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, observational studies, and case series published in English-language peer-reviewed journals.

All studies had to meet the following pre-defined inclusion criteria: (1) Original studies; (2) Studies involving adult patients diagnosed with advanced cancer; (3) Interventions that involve the administration of psilocybin or psilocybin-containing substances; (4) Studies reporting outcomes related to quality of life, pain control, or anxiety relief; (5) Ran

Studies that satisfied the following criteria were excluded: (1) Studies involving pediatric patients or patients without advanced cancer; (2) Studies without clear methodology or outcome measures; (3) Studies not published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., conference abstracts, posters); (4) Animal studies or in vitro studies; or (5) Duplicate publications or multiple reports from the same study (only the most comprehensive report will be included).

We utilized a systematic methodology to gather information from the studies included in our analysis. In this study, the data extraction process was conducted by two independent reviewers (Husam B and Farraj H) utilizing a predefined form specifically designed for this purpose. Any discrepancies or inconsistencies between the reviewers were addressed through constructive dialogue, with careful reference to the predetermined criteria outlined for the study. In instances where disagreements persisted, resolution was facilitated by third-party arbitration, overseen by reviewer Abu Omar Y. This approach ensured strict adherence to established guidelines and served to mitigate potential subjective biases inherent in the analysis process. The extracted data included the following categories: (1) Author name; (2) Publication year; (3) Study design; (4) Sample size; (5) Mean age (SD); (6) Cancer diagnosis; (7) Intervention details; and (8) Findings.

In instances where studies were accompanied by multiple reports, we diligently examined all accessible publications and chose the most pertinent one for integration into our analysis. If several reports were incorporated for a singular study, we took measures to avoid data redundancy and worked to amalgamate information across these reports. This approach was adopted to uphold the integrity and thoroughness of our analysis.

The Cochrane Handbook's Risk of Bias assessment tool will be employed to evaluate randomized controlled trials (Higgins et al[21], 2011). Each study will undergo scrutiny and categorization into "high risk", "low risk", or "unclear" across various domains, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential biases.

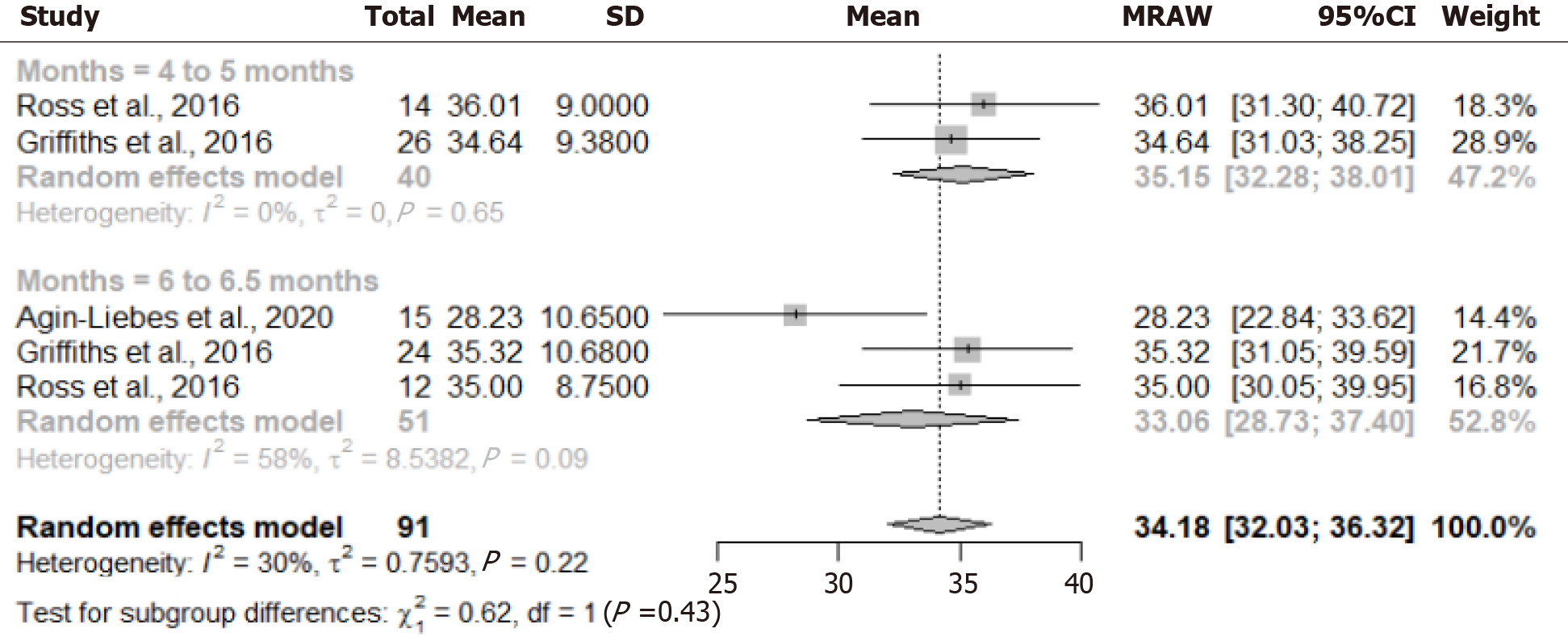

In our meta-analysis, we employed a single proportion rate to assess the efficacy of anxiety relief measured by The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) TRAIT scale. For categorical factors, proportions along with their corresponding 95%CIs were calculated, while mean or median values were determined for continuous data whenever possible. Pooled means and proportions were then computed utilizing random-effects models, accounting for the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the included studies. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 statistics and Cochran Q test values, with an I2 value exceeding 50% indicative of high statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50% and P < 0.05). A forest plot was generated to assess the potential presence of publication bias. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2).

Our meta-analysis primarily focused on assessing the impact of psilocybin on anxiety levels. It is important to note that while several studies examined various effects of psilocybin on patients with advanced cancers beyond anxiety, the heterogeneity in symptom reporting and study structures precluded achieving consistent homogeneity necessary for conducting a meta-analysis across all these symptoms. For instance, while some studies reported on "existential well-being", others focused on "quality of life". Although these concepts may exhibit proximity or overlap in definition, deeming them interchangeable for mathematical meta-analysis could introduce ambiguity. Consequently, the investigators opted for a more stringent approach in their quantitative analysis to maintain methodological rigor.

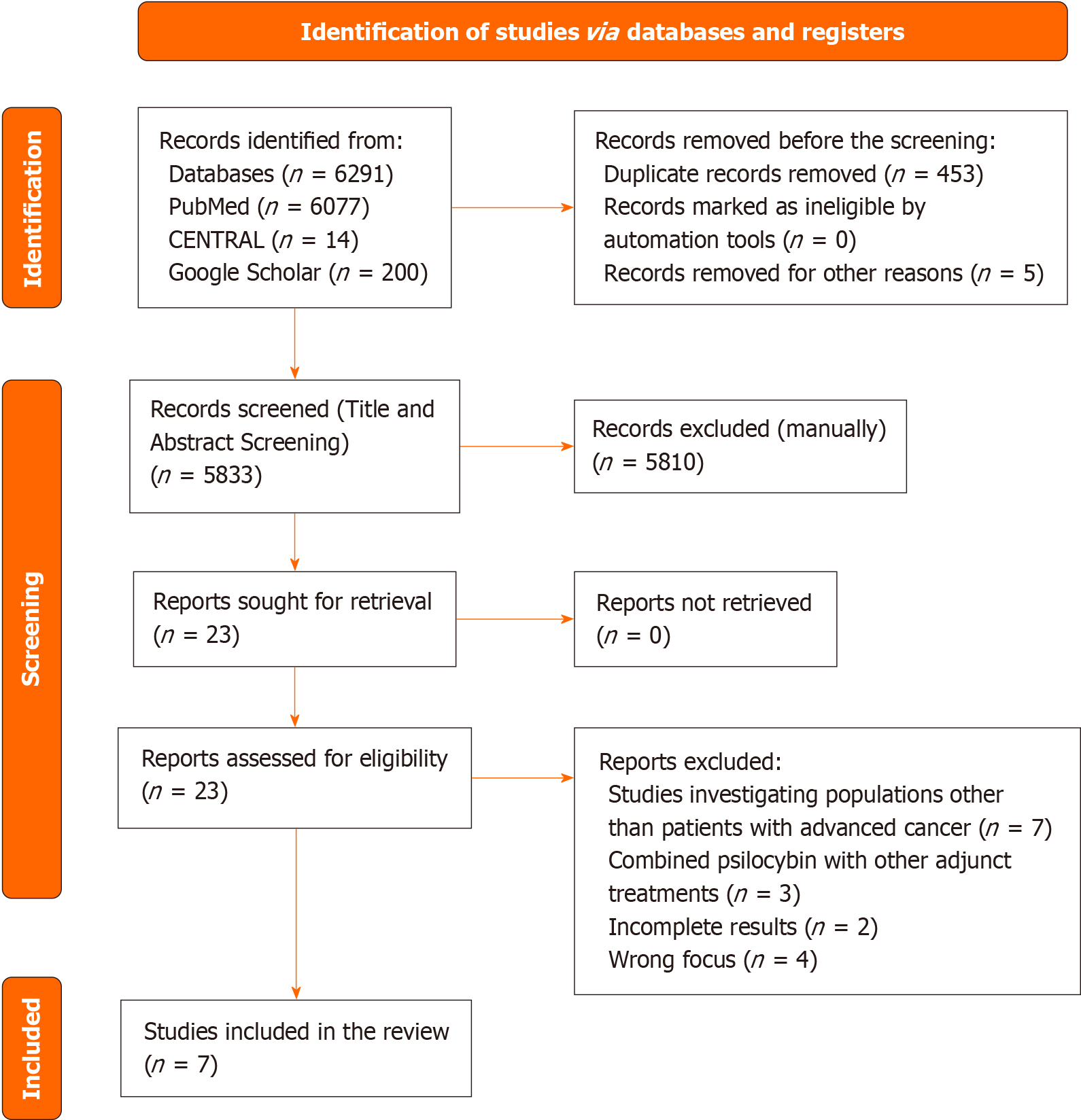

The primary search yielded a total of 6291 articles across the databases: 14 from CENTRAL, 6077 from PubMed, and 200 from Google Scholar. Following the removal of 453 duplicate articles, 5810 articles were excluded during the title and abstract screening phase based on the eligibility criteria. Subsequently, the remaining 23 articles underwent full-text review, resulting in the exclusion of 16 articles due to incomplete fulfilment of the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 7 studies were included in the systematic review, while 3 studies were incorporated into the meta-analysis. The rationales for exclusion are delineated in the PRISMA flowchart depicted in Figure 1.

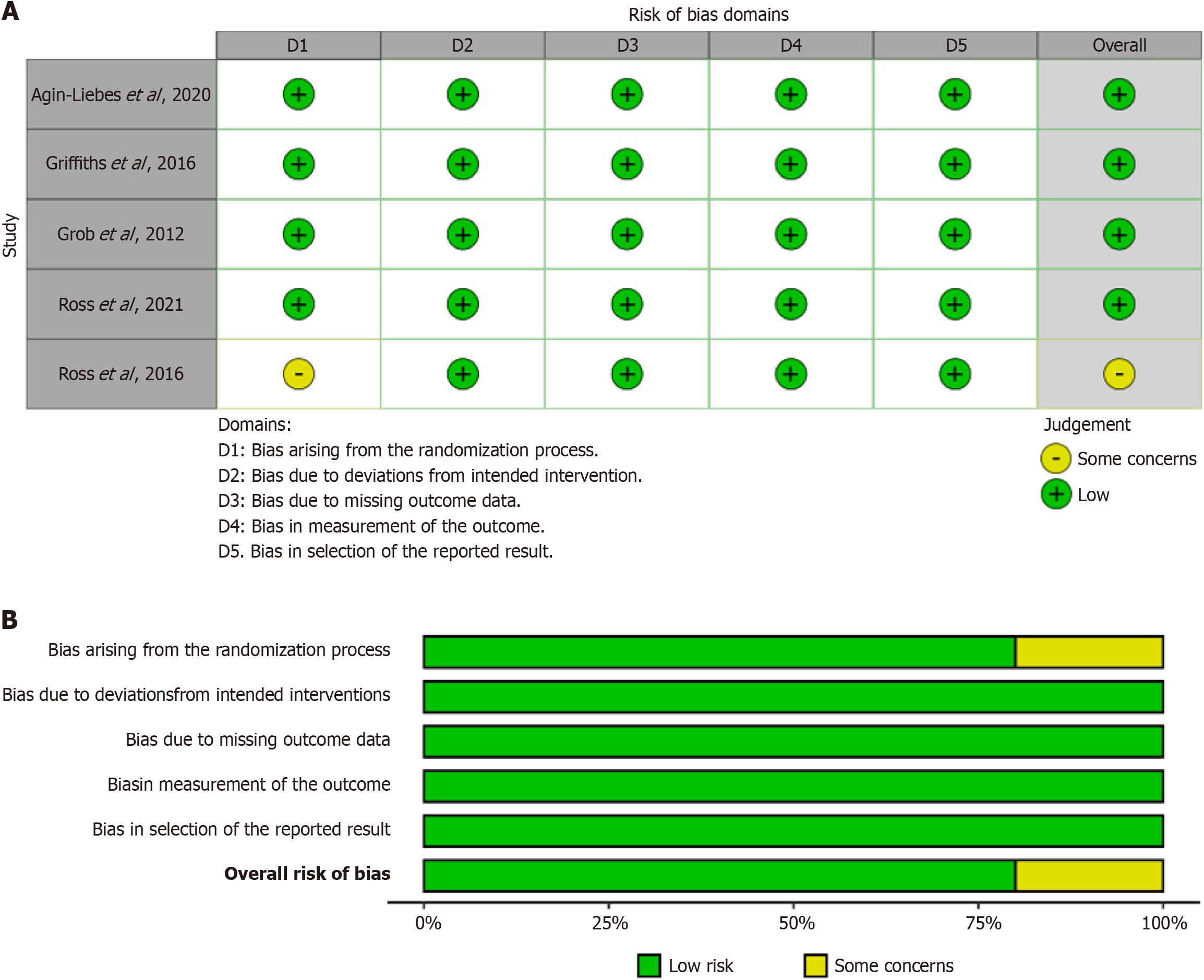

Four of the randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were deemed to have low-risk overall quality, while one trial raised some concerns in this regard. This assessment is depicted in Figure 2.

Characteristics of included studies: As shown in Table 2, this paper includes findings from a total of 7 studies, comprising 5 RCTs, 1 observational study, and 1 qualitative interview study. Across these studies, the sample sizes varied, with RCTs ranging from 11 to 51 participants, while the observational study involved a single participant. In terms of gender distribution, the percentage of male participants ranged from 0% in the observational study to 54% in the qualitative interview study. The mean ages of participants ranged from 50 to 60.3 years across the studies. The cancer diagnoses encompassed a wide spectrum, including breast, reproductive, lymphoma, colon, ovarian, peritoneal, salivary gland, multiple myeloma, and other types of cancer. Intervention details varied among the studies, with treatments including psilocybin administration at different dosages, niacin as a placebo, and qualitative interviews exploring par

| Ref. | Publication year | Study design | Sample size | Mean age (SD) | Cancer diagnosis | Intervention details | Findings |

| Agin-Liebes et al[22] | 2020 | Randomized controlled trial | 15, 40% Male | 53 (15.5) | Various cancer types (breast, Reproductive, Lymphoma, and other types), stage I to IV | Psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg) on the first medication session followed by niacin (250 mg) on the second session (i.e. psilocybin-first group), or niacin (250 mg) on the first medication session followed by psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg) on the second session (i.e. niacin-first group) | Reductions in anxiety, depression, hopelessness, demoralization, and death anxiety were sustained at the first and second follow-ups. Participants overwhelmingly attributed positive life changes to the psilocybin-assisted therapy experience and rated it among the most personally meaningful and spiritually significant experiences of their lives |

| Griffiths et al[17] | 2016 | Randomized controlled trial | 51, 51% Male | 56.3 | All 51 participants had a potentially life-threatening cancer diagnosis, with 65% having recurrent or metastatic disease. Types of cancer included breast (13 participants), upper aerodigestive (7), gastrointestinal (4), genitourinary (18), hematologic malignancies (8), and other (1) | The low-dose-1st group received the low dose (1 or 3 mg/70 kg) of psilocybin on the first session and the high dose on the second session, whereas the high-dose-1st group (22 or 30 mg/70 kg) received the high dose on the first session and the low dose on the second session | High-dose psilocybin produced large decreases in clinician- and self-rated measures of depressed mood and anxiety, along with increases in quality of life, life meaning, and optimism, and decreases in death anxiety. At 6-month follow-up, these changes were sustained, with about 80% of participants continuing to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety. Participants attributed improvements in attitudes about life/self, mood, relationships, and spirituality to the high-dose experience, with > 80% endorsing moderately or greater increased well-being/life satisfaction |

| Grob et al[16] | 2011 | Randomized controlled trial | 12, 8% Male | Subjects ages ranged from 36 to 58 years | Primary cancers included breast cancer in 4 subjects, colon cancer in 3, ovarian cancer in 2, peritoneal cancer in 1, salivary gland cancer in 1, and multiple myeloma in 1. All subjects were in the advanced stages of their illness. | Each subject acted as his or her control and was provided 2 experimental treatment sessions spaced several weeks apart. They were informed that they would receive active psilocybin (0.2 mg/kg) on one occasion and the placebo, niacin (250 mg), on the other occasion. Psilocybin and placebo were administered in clear 00 capsules with corn starch and swallowed with 100 mL of water. A niacin placebo was chosen because it often induces a mild physiological reaction (e.g., flushing) without altering the psychological state. The order in which subjects received the 2 different treatments was randomized and known only by the research pharmacist. Treatment team personnel remained at the bedside with the subject for the entire 6-hour session | During treatment sessions, safe physiological and psychological reactions were observed. No significant adverse events related to psilocybin were reported. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory showed a notable decrease in anxiety levels at 1 and 3 months post-treatment. Improvement in mood, as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory, became significant by the 6-month mark. Additionally, the Profile of Mood States indicated an enhancement in mood following psilocybin treatment, although this improvement did not quite reach statistical significance |

| Patchett-Marble et al[23] | 2022 | Observational study | 1, 0% Male | 54 | Advanced lung cancer and substantial existential and psychological distress | The patient consumed 5 g of dried psilocybin mushrooms as a tea and was directed to go inward as she laid down with eye shades on and headphones playing gentle, guiding music. A quantity of 5 g was selected to approximate the dose of psilocybin used in clinical trials, based on reports of psilocybin concentrations in the Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms that she was to consume | In line with psilocybin administration in clinical studies, the single psilocybin session prompted a mystical encounter for the patient, which she later regarded as the most profoundly meaningful experience of her life. This encounter resulted in immediate, significant, and lasting enhancements in her well-being and overall quality of life |

| Ross et al[24] | 2021 | Randomized controlled trial | 11, 36.4% Male | 60.3 (7.1) | Patients were diagnosed with cancer at various sites, including breast, reproductive, lymphoma/leukemia, colon, and others, across stages I through IV | A controlled trial was designed to assess the efficacy of a single, moderate-to-high dose of oral psilocybin per session (0.3 mg/kg) vs a single-dose session of an orally administered active control (niacin 250 mg) | In individuals exhibiting elevated SI at baseline, PAP demonstrated significant reductions in suicidal ideation as early as 8 hours post-administration, persisting for 6.5 months thereafter. Additionally, PAP led to substantial decreases in Loss of Meaning from baseline, evident 2 weeks post-treatment and maintaining significance at 6.5 months, as well as at the 3.2 and 4.5-year follow-ups. Exploratory analyses support the hypothesis that PAP could serve as an effective intervention against suicidality following a cancer diagnosis, attributed to its positive effects on hopelessness, demoralization, and particularly its impact on meaning-making |

| Ross et al[25] | 2016 | Randomized controlled trial | 29, 38% Male | 56.28 (12.93) | Nearly two-thirds of participants (62%) had advanced cancers (stages III or IV). The types of cancer included: Breast or reproductive (59%); gastrointestinal (17%); hematologic (14%); and other (10%) | Psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg) first then niacin (250 mg) second, or niacin (250 mg) first then psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg) second | Psilocybin elicited immediate, significant, and enduring enhancements in anxiety and depression levels, alongside reductions in cancer-related demoralization and hopelessness. It also resulted in improved spiritual well-being and heightened quality of life. Follow-up assessments at 6.5 months revealed persistent anxiolytic and antidepressant effects, with approximately 60-80% of participants maintaining clinically significant reductions in depression or anxiety. Furthermore, sustained improvements were noted in existential distress and overall quality of life, along with a positive shift in attitudes towards death. It was observed that the therapeutic impact of psilocybin on anxiety and depression was mediated by the psilocybin-induced mystical experience |

| Swift et al[26] | 2017 | Qualitative interview study | 13, 54% male | 50 (15.77) | The distribution of cancer stages among participants is as follows: 31% were diagnosed with Stage I cancer, 15% with Stage II, 31% with Stage III, 15% with Stage IV, and 8% with other stages. Regarding the site of cancer, the breakdown is as follows: 23% of cases were in the breast, 15% in lymphoma, 31% in other locations, and 31% in the ovarian region | Participants were randomized to receive either: (1) Psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg) first and niacin (250 mg) second; or (2) niacin (250 mg) first and psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg) second | Participants recounted the intense and emotionally challenging impact of the psilocybin session, resulting in a profound acceptance of mortality, recognition of cancer's role in life, and a detachment from the emotional burden of the disease. Many participants interpreted their experiences through a spiritual or religious lens, finding that psilocybin therapy aided in reestablishing a deep connection with life, reclaiming a sense of presence, and fostering increased resilience against potential cancer relapse |

Results of included studies: In a study conducted by Agin-Liebes et al[22], a randomized controlled trial explored the long-term effects within a subset of participants who had completed the initial trial. Out of the 16 participants still living, all were approached for follow-up, with 15 agreeing to participate. The follow-up assessments were conducted on average at 3.2- and 4.5 years post-psilocybin administration. The findings revealed sustained reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression, despair, and death anxiety at both follow-up points. Furthermore, a significant majority of par

Another investigation conducted by Grob et al[16] focused on examining the safety and effectiveness of psilocybin in individuals with advanced-stage cancer and reactive anxiety. The researchers noted a positive trend toward enhanced mood and reduced anxiety. No clinically significant adverse events were reported in association with psilocybin administration. Analysis of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory trait anxiety subscale indicated a significant decrease in anxiety levels at 1- and 3 months post-treatment. The Beck Depression Inventory also highlighted a mood improvement that became significant at the 6-month mark. Furthermore, the profile of mood states identified an enhancement in mood following psilocybin treatment, although it did not reach statistical significance. According to a case report by Patchett-Marble et al[23], similar to findings in clinical trials involving psilocybin, a single session of psilocybin induced a mystical encounter for the patient. This encounter was later described by the patient as the most profoundly meaningful ex

A study conducted by Ross et al[25] found that psilocybin elicited immediate, considerable, and lasting improvements in anxiety and depression, while also decreasing cancer-related demoralization and hopelessness. Additionally, it en

The Figure 3 illustrates the changes in anxiety levels, as measured by the STAI scale, at two-time points following the administration of psilocybin to patients with advanced cancer. At the initial assessment conducted 4 to 5 months after psilocybin administration, the pooled mean anxiety level was 35.15 (95%CI: 32.28-38.01). Subsequent evaluation at 6 to 6.5 months post-administration revealed a decrease in the pooled mean anxiety level to 33.06 (95%CI: 28.73-37.40). The observed decrease in anxiety levels suggested a potential therapeutic effect of psilocybin in mitigating anxiety among patients with advanced cancer over time. The non-overlapping confidence intervals between the two-time points indicated a statistically significant difference in anxiety levels.

Psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain species of mushrooms, has gained increasing attention in recent years for its potential therapeutic effects, particularly in the context of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. Considering this growing interest, the present systematic review and meta-analysis sought to investigate the effects of psilocybin on the quality of life, pain control, and anxiety relief in adults with advanced cancer, addressing the pressing need for novel interventions to alleviate the psychological distress associated with this terminal illness.

The findings from the included studies provided compelling evidence for the therapeutic potential of psilocybin-assisted therapy in this patient population. For instance, the study by Agin-Liebes et al[22] revealed sustained reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression, hopelessness, demoralization, and death anxiety among participants, with many att

The findings of this review are largely consistent with existing literature on the therapeutic effects of psilocybin in patients with advanced cancer. Several previous studies have reported similar outcomes, demonstrating significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression, and existential distress following psilocybin-assisted therapy. For example, the results of Agin-Liebes et al[22] in 2020 align with those of previous research by Lewis et al[27] and Malone et al[28] in 2018, which also documented sustained improvements in psychological well-being and quality of life among cancer patients treated with psilocybin. Similarly, the study by Agrawal et al[29] reported positive trends toward en

One potential explanation for variations in treatment response could be differences in the dosage or administration of psilocybin. For example, Griffiths et al[17] administered high doses of psilocybin, whereas Grob et al[16] used a moderate dose, and Ross et al[25] employed a single moderate dose combined with psychotherapy. These variations in dosing and administration may have influenced the magnitude and duration of therapeutic effects observed in each study. Additionally, differences in patient populations, such as variations in cancer stage, treatment history, or psychological comorbidities, may also contribute to variability in treatment outcomes. For instance, patients with more advanced disease or greater psychological distress may exhibit different response patterns compared to those with earlier-stage disease or milder symptoms.

Overall, while there may be some discrepancies in the literature, the consensus among studies suggests that psilocybin-assisted therapy holds promise as a valuable intervention for improving the psychological well-being and quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. Future research efforts should address these discrepancies through well-designed, controlled trials that systematically investigate the optimal dosing, administration, and patient selection criteria for psilocybin-assisted therapy in this population.

Reflecting on the strengths and limitations of the studies included in this review is essential for interpreting the findings and understanding their implications. One of the strengths of the studies included in this review is their use of RCT designs, which provide a rigorous methodological framework for evaluating the efficacy and safety of psilocybin therapy. Additionally, many of the studies employed standardized outcome measures, allowing for comparability across studies and enhancing the validity of the findings. However, sample size limitations were a common issue across the studies, with small sample sizes in some cases limiting the generalizability of the findings. This is particularly relevant given the variability in patient populations and treatment protocols across studies, which may influence the magnitude and durability of treatment effects.

This systematic review and meta-analysis provided a comprehensive synthesis of the evidence regarding the effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on quality of life, pain control, and anxiety relief in patients with advanced cancer. The findings of this review highlight the potential of psilocybin as a novel therapeutic intervention for addressing the com

| 1. | Mok E, Lau KP, Lam WM, Chan LN, Ng JS, Chan KS. Healthcare professionals' perceptions of existential distress in patients with advanced cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1510-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Henoch I, Danielson E. Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: an integrative literature review. Psychooncology. 2009;18:225-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schimmers N, Breeksema JJ, Smith-Apeldoorn SY, Veraart J, van den Brink W, Schoevers RA. Psychedelics for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and existential distress in patients with a terminal illness: a systematic review. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239:15-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Paice JA, Ferrell B. The management of cancer pain. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:157-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta D, Lis CG, Grutsch JF. The relationship between cancer-related fatigue and patient satisfaction with quality of life in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vehling S, Kissane DW. Existential distress in cancer: Alleviating suffering from fundamental loss and change. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2525-2530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Greer JA, Applebaum AJ, Jacobsen JC, Temel JS, Jackson VA. Understanding and Addressing the Role of Coping in Palliative Care for Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:915-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Holland JC. History of psycho-oncology: overcoming attitudinal and conceptual barriers. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:206-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anand U, Dey A, Chandel AKS, Sanyal R, Mishra A, Pandey DK, De Falco V, Upadhyay A, Kandimalla R, Chaudhary A, Dhanjal JK, Dewanjee S, Vallamkondu J, Pérez de la Lastra JM. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis. 2023;10:1367-1401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 284.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Carey MP, Burish TG. Etiology and treatment of the psychological side effects associated with cancer chemotherapy: a critical review and discussion. Psychol Bull. 1988;104:307-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: an integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:604-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sessa B. Why psychiatry needs psychedelics and psychedelics need psychiatry. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moujaes F, Preller KH, Ji JL, Murray JD, Berkovitch L, Vollenweider FX, Anticevic A. Toward Mapping Neurobehavioral Heterogeneity of Psychedelic Neurobiology in Humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93:1061-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, Carpenter LL, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, Kalin NH, McDonald WM; the Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments, a Division of the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research. Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:391-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 64.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schenberg EE. Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Paradigm Shift in Psychiatric Research and Development. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, Hagerty M, McKay CR, Halberstadt AL, Greer GR. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 48.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, Cosimano MP, Klinedinst MA. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1181-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1461] [Cited by in RCA: 1190] [Article Influence: 132.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rahbarnia A, Li Z, Fletcher PJ. Effects of psilocybin, the 5-HT(2A) receptor agonist TCB-2, and the 5-HT(2A) receptor antagonist M100907 on visual attention in male mice in the continuous performance test. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2023;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Carter OL, Burr DC, Pettigrew JD, Wallis GM, Hasler F, Vollenweider FX. Using psilocybin to investigate the relationship between attention, working memory, and the serotonin 1A and 2A receptors. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:1497-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2603] [Cited by in RCA: 4300] [Article Influence: 1075.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 21. | Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18487] [Cited by in RCA: 24610] [Article Influence: 1757.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 22. | Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponté KL, Guss J, Bossis AP, Grigsby J, Fischer S, Ross S. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34:155-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Patchett-Marble R, O'Sullivan S, Tadwalkar S, Hapke E. Psilocybin mushrooms for psychological and existential distress: Treatment for a patient with palliative lung cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2022;68:823-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ross S, Agin-Liebes G, Lo S, Zeifman RJ, Ghazal L, Benville J, Franco Corso S, Bjerre Real C, Guss J, Bossis A, Mennenga SE. Acute and Sustained Reductions in Loss of Meaning and Suicidal Ideation Following Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for Psychiatric and Existential Distress in Life-Threatening Cancer. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, Schmidt BL. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1165-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1162] [Cited by in RCA: 949] [Article Influence: 105.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Swift TC, Belser AB, Agin-liebes G, Devenot N, Terrana S, Friedman HL, Guss J, Bossis AP, Ross S. Cancer at the Dinner Table: Experiences of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Distress. J Humanisti Psychol. 2017;57:488-519. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lewis BR, Garland EL, Byrne K, Durns T, Hendrick J, Beck A, Thielking P. HOPE: A Pilot Study of Psilocybin Enhanced Group Psychotherapy in Patients With Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;66:258-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Malone TC, Mennenga SE, Guss J, Podrebarac SK, Owens LT, Bossis AP, Belser AB, Agin-Liebes G, Bogenschutz MP, Ross S. Individual Experiences in Four Cancer Patients Following Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Agrawal M, Richards W, Beaussant Y, Shnayder S, Ameli R, Roddy K, Stevens N, Richards B, Schor N, Honstein H, Jenkins B, Bates M, Thambi P. Psilocybin-assisted group therapy in patients with cancer diagnosed with a major depressive disorder. Cancer. 2024;130:1137-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |