Published online Apr 24, 2023. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v14.i4.171

Peer-review started: February 13, 2023

First decision: March 28, 2023

Revised: April 6, 2023

Accepted: April 13, 2023

Article in press: April 13, 2023

Published online: April 24, 2023

Processing time: 66 Days and 14.5 Hours

Along with the discovery and refinement of serrated pathways, the World Health Organization amended the classification of digestive system tumors in 2019, recommending the renaming of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps to sessile serrated lesions (SSLs). Given the particularity of the endoscopic appearance of SSLs, it could easily be overlooked and missed in colonoscopy screening, which is crucial for the occurrence of interval colorectal cancer. Existing literature has found that adequate bowel preparation, reasonable withdrawal time, and awareness of colorectal SSLs have improved the quality and accuracy of detection. More particularly, with the continuous advancement and development of endoscopy technology, equipment, and accessories, a potent auxiliary tool is provided for accurate observation and immediate diagnosis of SSLs. High-definition white light endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and magnifying endoscopy have distinct roles in the detection of colorectal SSLs and are valuable in identifying the size, shape, character, risk degree, and potential malignant tendency. This article delves into the relevant factors influencing the detection rate of colorectal SSLs, reviews its characteristics under various endoscopic techniques, and expects to attract the attention of colonoscopists.

Core Tip: Because of its unique endoscopic patterns and behavior, sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) are easily missing during colonoscopy. SSL is a critical cause of interval colorectal cancer, so it is necessary to summarize the endoscopic features of the sessile serrated lesion to help endoscopists make a better identification and diagnosis.

- Citation: Wang RG, Wei L, Jiang B. Current progress on the endoscopic features of colorectal sessile serrated lesions. World J Clin Oncol 2023; 14(4): 171-178

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v14/i4/171.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v14.i4.171

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common gastrointestinal malignancy with the third-highest incidence and the second-highest mortality rate. In China, more than 550000 new cases were diagnosed and 280000 deaths took place in 2020[1], severely threatening people's lives and health. With the improvements in awareness concerning colonoscopic screening, the occurrence of interval CRC has garnered significant attention. Interval CRC refers to the CRC that is not detected during colorectal screening but discovered prior to the next recommended screening date[2]. The incidence of interval CRC is a vital indicator in assessing the quality of colonoscopic screening. Interval CRC detection in the proximal colon goes beyond being merely a test of the patient's bowel preparation since the colonoscopist’s experience is also highly relevant.

Colorectal sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) are poorly defined and pale, covered with mucus, and hardly distinguishable from the surrounding mucosa. For endoscopists who lack awareness of the features of colorectal SSLs, missing or overlooking them becomes inevitable, resulting in the incidence of interval CRCs[3]. Related research observed that the occurrence of interval CRCs three years after colonoscopy was 3.4%-9.0%[2,4].

Colorectal SSLs may proceed to CRCs through the pathways of BRAF mutation, microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation, and the deletion gene of DNA damage repair[5]. It has been exhibited that a 15%-30% incidence of CRCs occurs via the serrated pathway, which is known as the vital cancer pathway[5,6].

During the previous decade, related studies have generated a more accurate description of the pathogenesis of intestinal adenocarcinoma. Population-based screening for CRCs has led to a comprehensive understanding of precancerous lesions and established a foundation for investigating the molecular pathways and biological behaviors of cancerous lesions. Accordingly, WHO renamed the sessile serrated adenoma/polyp as SSLs, as these may be flat rather than polypoid, and the association with BRAF or KRAS mutation delineates two separate neoplastic pathways.

Currently, the categorization of gastrointestinal tumors classifies serrated lesions as Hyperplastic Polyps (HP), SSL, SSL with dysplasia (SSL-D), Traditional serrated adenomas (TSA), and serrated tubular villous adenoma (STVA)[7-9].

HP is a benign lesion, and the pathological features are primarily epithelial hyperplasia in the upper 2/3 of the saphenous fossa, forming small papillae protruding into the lumen of the saphenous fossa, which then gives the luminal surface a serrated shape. Based on the cell composition and molecular genetic alterations, the two types of HP are the Microvesicular type of Hyperplastic Polyp and the Goblet Cell-rich type of Hyperplastic Polyp. Generally, the TSA is pedicled and has villous structures but is potentially malignant[10-12]. In contrast to the conventional tubulovillous adenoma, STVA usually presents histological changes in advanced adenomas, and the glands are frequently serrated when high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma appear.

The histological diagnosis of SSLs necessitates the detection of at least one abnormal crypt. By way of illustration, the entire saphenous fossa is serrated and grows horizontally along the mucosal muscular layer, the basal expansion, abnormal maturation, and asymmetric proliferation, in which asymmetric proliferation causes structural changes in the entire saphenous fossa. This is the fundamental difference from the HP[8]. Moreover, SSL-D is histologically heterogeneous. Its abnormal crypt structures—being its core feature—differ from the surrounding glands like the appearance of villous structures, which are longer and more crowded, complex branching, sieve-shaped crypt, and increased or decreased serration compared with the background SSL. The morphology of SSL-Ds is often tanglesome and mixed with different subtypes, making it challenging to distinguish the degree of heterogeneous hyperplasia.

It has been widely recognized that colorectal SSLs essentially differ from HPs, both with regard to morphological and pathological characteristics analysis, and instead behave comparably to neoplastic lesions with malignant potential.

Meta-analyses have demonstrated that SSLs are associated with an increased risk of concurrent progressive tumors. Patients with larger proximal colorectal serrated lesions are at significant risk and may require closer monitoring and further completion of a colon examination[13,14]. In light of this, a population-based, case-control study from Danish revealed that having an SSL was associated with 3-fold increased odds for CRC, while having SSL-D was associated with a nearly 5-fold increased odds for CRC[15,16].

Reports have confirmed that the risk of developing CRCs in cases with SSL-D is 4.4% within a decade, which is higher than that of conventional adenoma (2.3%). This highlights a significantly increased long-term risk of CRC in patients with SSL[16]. Similarly, correlative studies have found that SSLs have a mean duration of 7-15 years before developing SSL-Ds. Then, 3.03%-12.5% of SSLs develop into CRCs 5-7 years after follow-up[17,18]. However, SSL-Ds progress to CRCs at a much faster rate, and there are reports of SSL-Ds rapidly aggravating submucosal invasive carcinomas within one or two years[19-21].

As a critical influencing factor in the occurrence of interval CRCs, the detection rate of SSLs can effectively evaluate the quality of colonoscopy and assess the level of colonoscopists. A retrospective study that included more than 10000 colonoscopies found that bowel preparation, exit time, polyp diameter, and adenoma detection rate were linked to the SSL detection rate. Equally important, a multivariate analysis underlined that adenoma detection rate was an independent predictor of SSL detection rate, implying that patients who developed colorectal adenomas were at higher risk of complicating SSL[22].

Additionally, a colonoscopist’s professional experience is vital to the timely and accurate detection of colorectal SSLs. Li et al[23] noted that different colonoscopists are independent risk factors for the detection rate of proximal colonic serrated lesions. It underscores that inexperienced colonoscopists detected serrated lesions at only 16%-83% compared with their experienced counterparts. They also found that proximal serrated polyps are more common in men over 50 years old.

The development of an endoscopic technique delivers a reliable tool for detecting colorectal SSLs, which are not easily distinguishable from the background mucosa. To effectively prevent the incidence of interval CRCs, an early diagnosis and treatment of SSLs are crucial, thereby improving the quality of life and disease prognosis of patients.

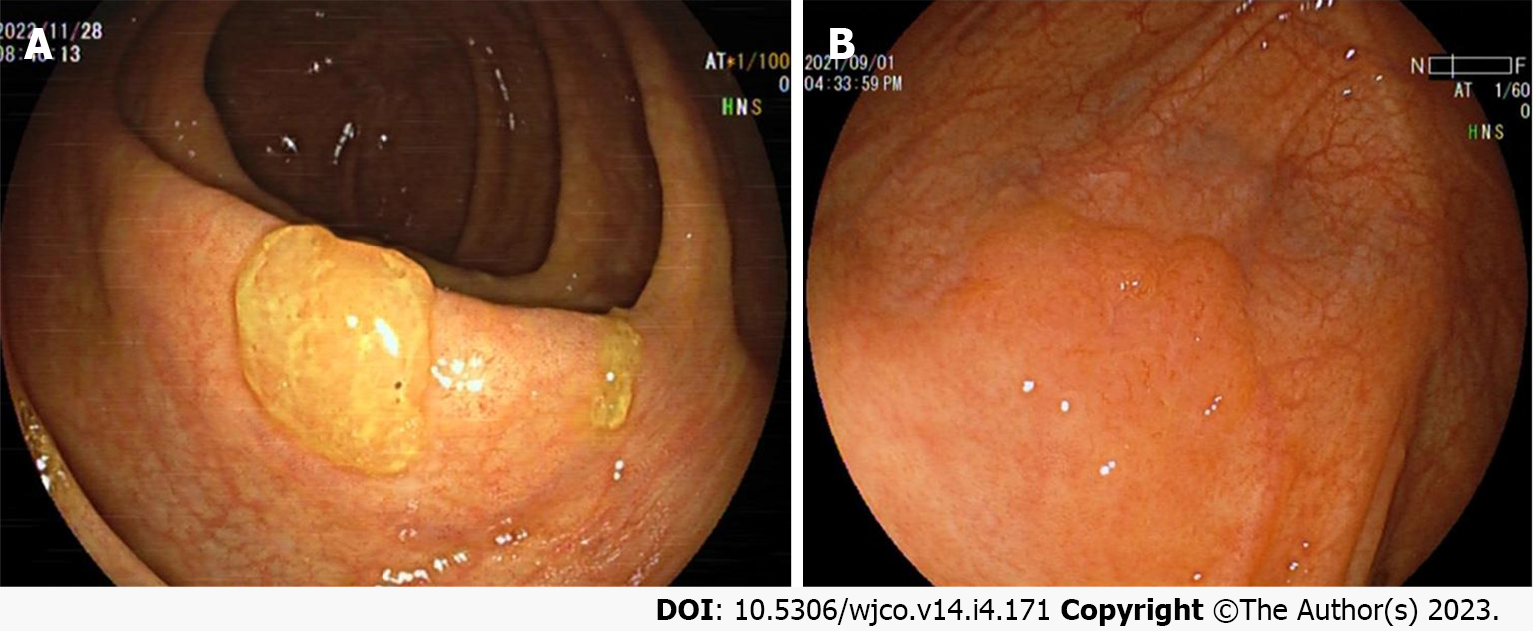

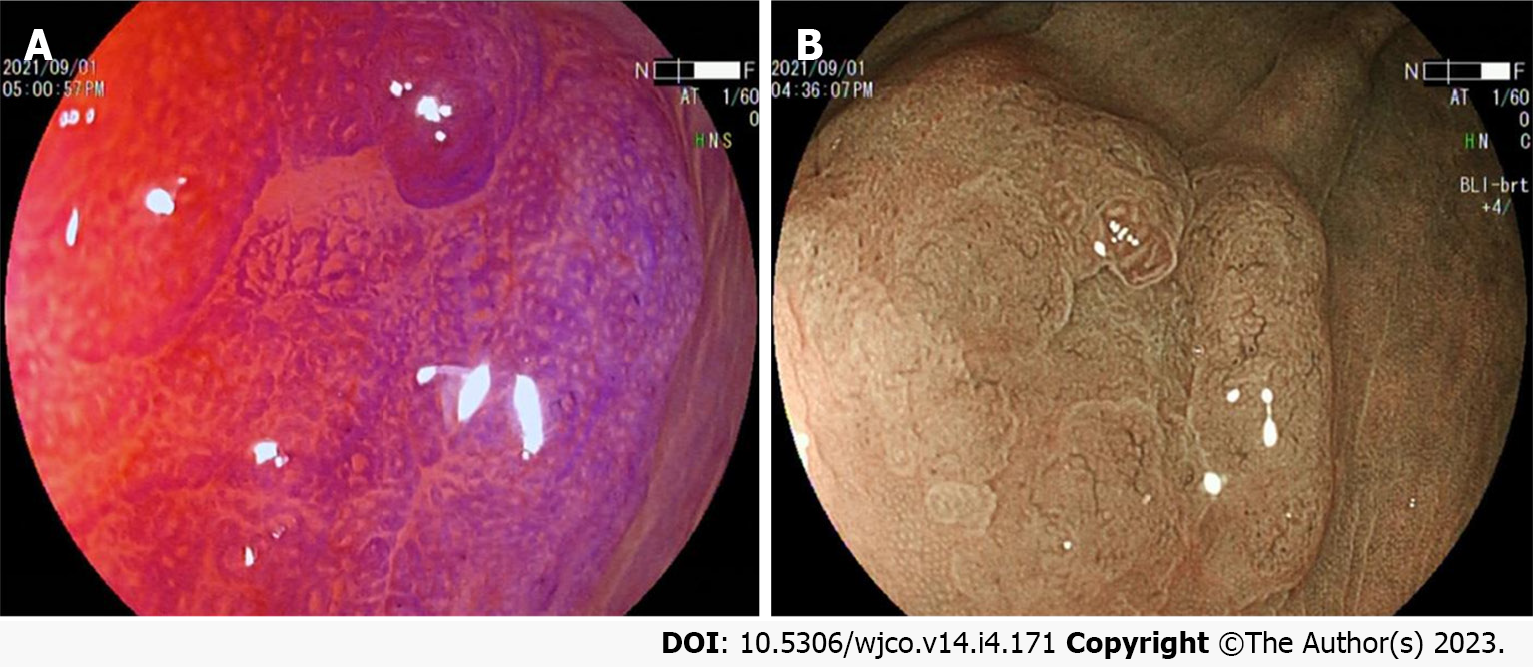

Colorectal SSL and SSL-D are prevalent in the proximal colon, usually > 5 mm in size, accounting for approximately 20%-25% of all serrated lesions. Additionally, colorectal SSLs often present with faint borders and a pale surface under white light endoscopy. Consequently, distinguishing them from the surrounding mucosa is difficult, making them prone to adverse events like missed or delayed diagnoses and incomplete resections. Most colorectal SSLs are accompanied by a mucus cap (Figure 1A), which, when flushed is not easily differentiated from HP. A further study also uncovered that inconspicuous borders and cloud-like surfaces are two independent diagnostic features of colorectal SSL in white light endoscopy[24-26]. Meanwhile, colorectal SSL-Ds are often associated with pedicled, bimodal appearance, central depression, and reddish color (Figure 1B), which can differentiate SSLs from SSL-Ds, with one of such features having a sensitivity of 97.7% and a specificity of 85.3% for the diagnosis of SSL-Ds[27].

Both HPs and SSLs are generally challenging and complex to identify when small (< 5 mm). To address this issue, the chromoendoscopy technique is adopted.

During endoscopy, chemical dyes (indigo carmine, crystalline violet, acetic acid, among several others) spray on the surface of the lesions, so the particles of the stains are deposited within the folds of the colorectal SSL lesion and surrounding mucosa. Then, the outlining of the lesion border and surface microstructure facilitates the assessment of SSL size and character.

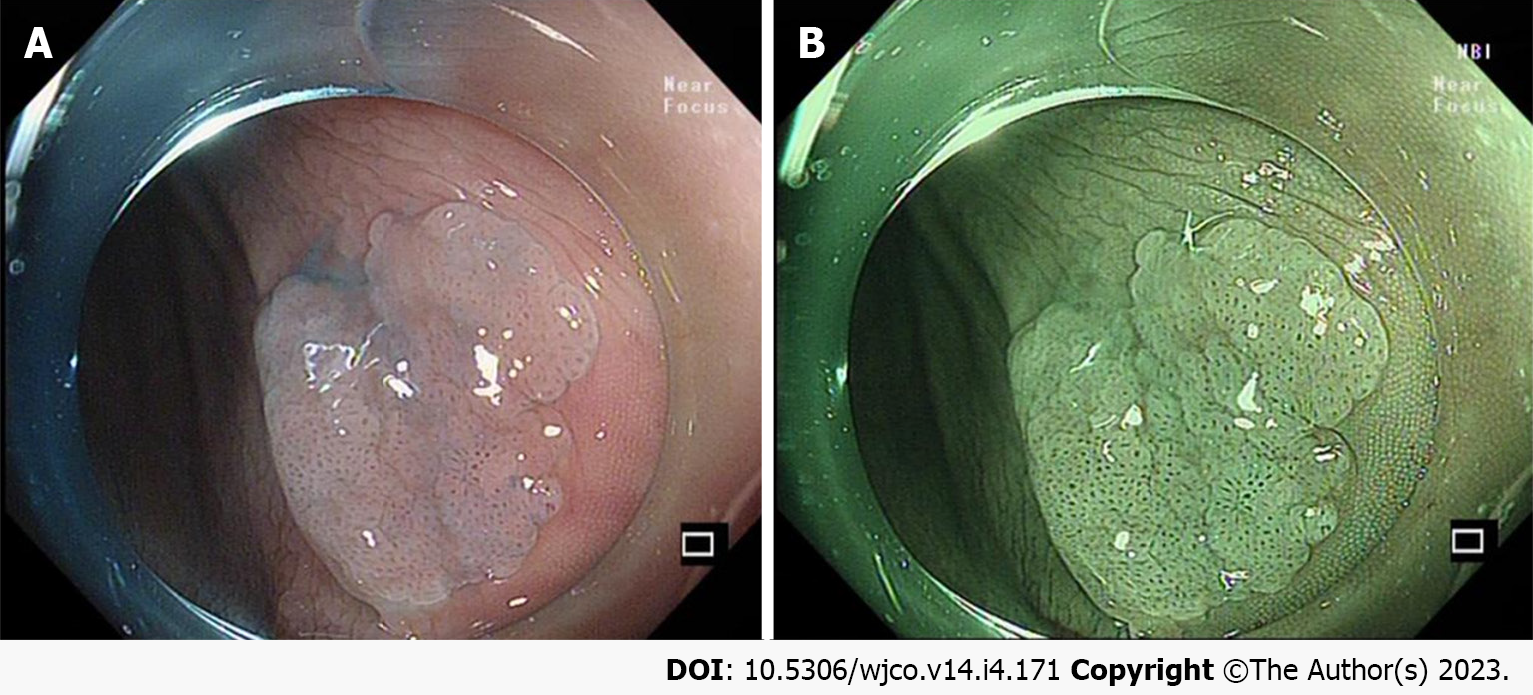

It is important to note that acetic acid spray plays an important role in showing the borders and diameter of colorectal SSLs (Figure 2A). The surface morphology of the SSL is clearer and more easily described after acetic acid spray, and its useful in better delineation of the recurrent colorectal SSL[28-30]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that acetic acid spray can help endoscopists perform cold resection of colorectal SSLs more accurately[31] (Figure 2B).

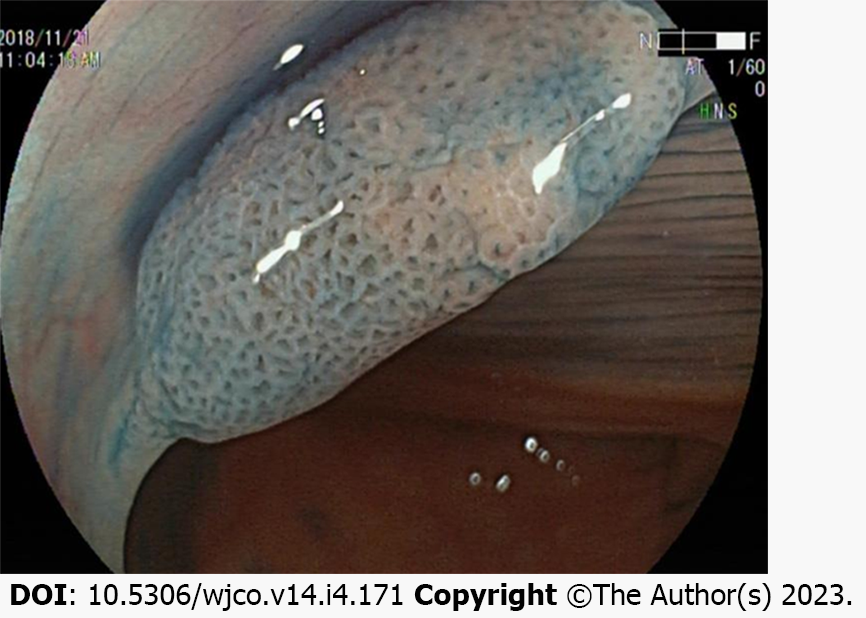

One study classified the chromoendoscopy images of the surface glands of more than 300 SSLs and indicated that open Type II (Pit II-O) structures, compared with the conventional Pit II type glands opening pattern, were endoscopic characteristics in colorectal SSLs[24]. Moreover, the opening pattern of the Pit II-O gland is similar to that of Pit II, and the former is typically surrounded by the latter, but the former features an expanded and more rounded shape, reflecting the expansion of the SSL crypt (Figure 3).

The image enhanced endoscopy (IEE) is the most common mode of electronic staining used in colonoscopy. Narrow band imaging (NBI) is a widely used IEE, which utilizes a filter to screen the broadband spectrum of the red, blue, and green light emitted by the light source, leaving only the narrowband spectrum for the diagnosis of various digestive disorders. Linked color imaging and blue laser imaging (BLI) are the next-generation IEEs, considering that their imaging principle is founded on light absorption and reflection by the mucosa of the digestive tract. Then, the lesions appear in a different color from the surrounding tissues, yielding a clear distinction between the superficial mucosal microvasculature and microstructure. It is also worth noting that the IEE has a brighter and higher resolution and is known as the "electron chromatography" technique given that the image observed by the IEE resembles a dye-stained image.

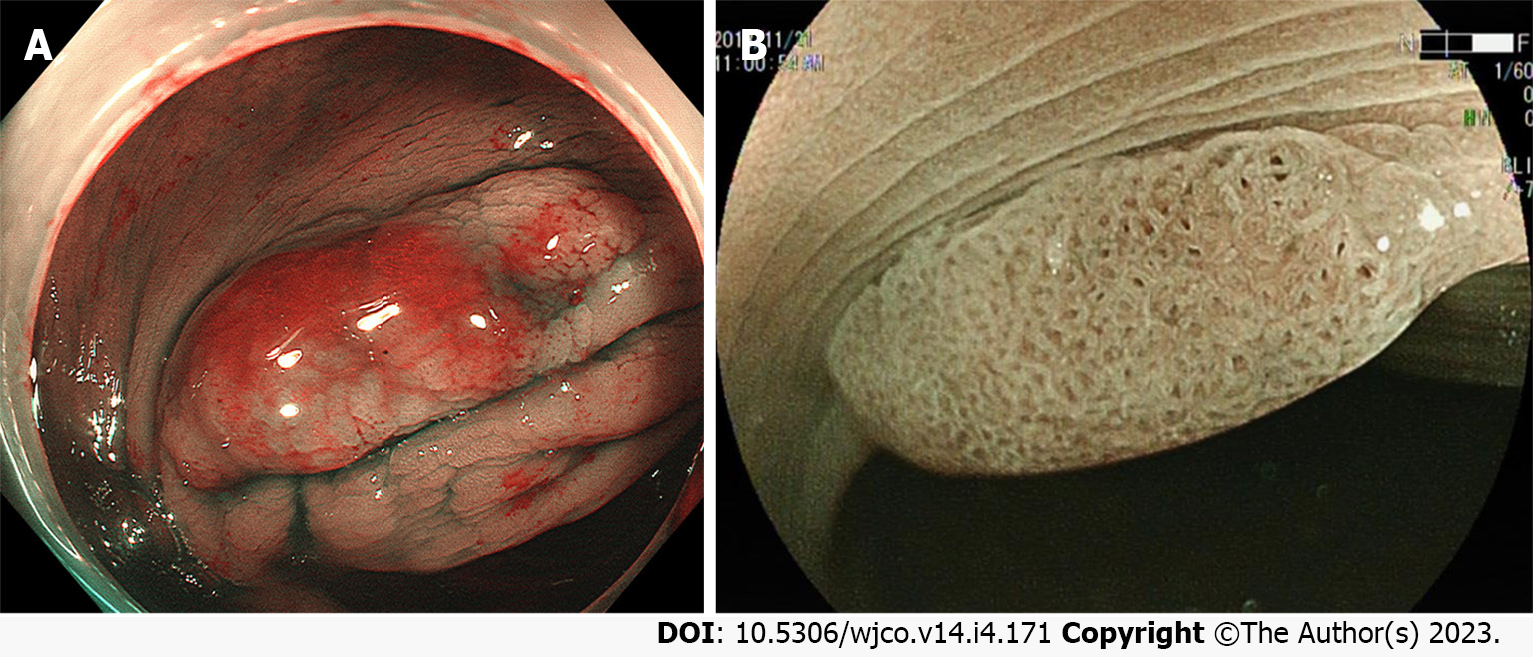

Furthermore, the NBI pattern enhances the visibility of colorectal SSLs with a mucus cap and gives it a concentrated red color that contrasts more prominently with the background mucosa[32] (Figure 4A). Also, both the NBI and BLI generally feature small black spots within the glandular opening of SSLs (Figure 4B), which is a critical histological feature within dependent diagnostic value that aids the endoscopist to differentiate SSLs from HPs during colonoscopy[25,33]. It has been confirmed that dilated and branching vessels in NBI endoscopy differs from the vascular surrounding superficial mucosal glands, and irregular capillaries may be observed at sites of colorectal SSL that show dysplasia[3,34,35].

Additional research showed that the multivariate analysis of the location (proximal colon), size (≥ 10 mm), glandular opening, and microvascular morphology of the serrated lesions exhibited more than 90% positive diagnosis of the SSL, which was 2.3 times more advantageous than its single factor diagnosis[36,37].

In identifying neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions, the value of magnified endoscopy combined with chromoscopy has been extensively evident. Close observation of the surface pattern of lesions with a specific combination can effectively predict its pathological characteristics and even the depth of invasion. Relevant literature has demonstrated that Type II-O glands can be used as an indicator to differentiate between SSLs and HPs. The Pit II-O glands also suggest histological variation in the morphology of colorectal SSL glands, significantly boosting the accuracy of diagnosing SSLs[38]. For large colorectal SSLs, magnified endoscopic findings of not only Type II-O glands but also those possibly mixed with Types IIIL, IV, Vi, and Vn glands at the same time often prompt SSL-Ds or cancers[24,27] (Figure 5A).

Magnified endoscopy combined with IEE can further develop the visualization of microvessels (Figure 5B). The varicose microvessels, running through the deep layer of mucosa, on the lesion surface of colorectal SSL, differ from those around the mucosal glands[37]. A similar study in China pointed out a statistical difference between magnified endoscopy and chromic endoscopy for varicose microvessels in predicting colorectal SSLs and HPs[35].

Colorectal SSL is potentially malignant and has a higher risk of malignancy than conventional tubular adenomas, thereby making an immediate diagnosis or early detection in colonoscopic screening especially important. However, the current diagnosis of SSLs in screening colonoscopy is undeniably insufficiently high and often depends on the histopathological diagnosis post-biopsy or resection. With advances in endoscopy equipment and imaging techniques, we have witnessed the role of cytoendoscopy in diagnosing gastrointestinal tract tumors[39]. In the future, we hope to discover a more objective and accurate factor in order to characterize the endoscopic presentation of colorectal SSLs, which can swiftly and efficiently identify lesions, reduce missed or delayed diagnoses, and effectively decrease the incidence of interval CRCs.

For colorectal SSLs, good bowel preparation is the foundation, and the endoscopist's knowledge and experience play an essential role. Ultimately, combining all the predictive factors in colonoscopy screening to generate an immediate diagnosis can improve the detection rate.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Choi YS, South Korea; Sano W, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64583] [Article Influence: 16145.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Sanduleanu S, le Clercq CM, Dekker E, Meijer GA, Rabeneck L, Rutter MD, Valori R, Young GP, Schoen RE; Expert Working Group on ‘Right-sided lesions and interval cancers’, Colorectal Cancer Screening Committee, World Endoscopy Organization. Definition and taxonomy of interval colorectal cancers: a proposal for standardising nomenclature. Gut. 2015;64:1257-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Fukushima H, Shibuya T, Yao T, Nagahara A. Usefulness of the Japan narrow-band imaging expert team classification system for the diagnosis of sessile serrated lesion with dysplasia/carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:4528-4538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Burr NE, Derbyshire E, Taylor J, Whalley S, Subramanian V, Finan PJ, Rutter MD, Valori R, Morris EJA. Variation in post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer across colonoscopy providers in English National Health Service: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2019;367:l6090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1570] [Cited by in RCA: 3016] [Article Influence: 502.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | East JE, Atkin WS, Bateman AC, Clark SK, Dolwani S, Ket SN, Leedham SJ, Phull PS, Rutter MD, Shepherd NA, Tomlinson I, Rees CJ. British Society of Gastroenterology position statement on serrated polyps in the colon and rectum. Gut. 2017;66:1181-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahadi M, Sokolova A, Brown I, Chou A, Gill AJ. The 2019 World Health Organization Classification of appendiceal, colorectal and anal canal tumours: an update and critical assessment. Pathology. 2021;53:454-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2430] [Article Influence: 486.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Li J, Teng XD, Lai MD. [Colorectal non-invasive epithelial lesions: an update on the pathology of colorectal serrated lesions and polyps]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:1339-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ng SC, Ching JY, Chan VC, Wong MC, Tang R, Wong S, Luk AK, Lam TY, Gao Q, Chan AW, Wu JC, Chan FK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Association between serrated polyps and the risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk individuals. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:108-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Crockett SD, Nagtegaal ID. Terminology, Molecular Features, Epidemiology, and Management of Serrated Colorectal Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:949-966.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Song YR, Song SZ, Gong AX. [Advancement in the study of carcinogenesis mechanism and endoscopic diagnosis of colorectal serrated lesions]. Chinese Journal of Digestive Endoscopy. 2021;38(5): 412-415. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Jung YS, Park JH, Park CH. Serrated Polyps and the Risk of Metachronous Colorectal Advanced Neoplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:31-43.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao Q, Tsoi KK, Hirai HW, Wong MC, Chan FK, Wu JC, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Ng SC. Serrated polyps and the risk of synchronous colorectal advanced neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:501-9; quiz 510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Robertson DJ, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Rex DK. Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1131-1153.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Snover DC, Torlakovic EE, Pedersen L, Frøslev T, Vyberg M, Hamilton SR, Sørensen HT. Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Development Among Patients With Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:895-902.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | IJspeert JE, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia-role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Deng JW, Fang JW. [Pathway and clinical characteristics of serrated colorectal cancer]. National Medical Journal of China. 2020;100 (34): 2716-2720. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Omori K, Yoshida K, Tamiya S, Daa T, Kan M. Endoscopic Observation of the Growth Process of a Right-Side Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp with Cytological Dysplasia to an Invasive Submucosal Adenocarcinoma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2016;2016:6576351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kinoshita S, Nishizawa T, Uraoka T. Progression to invasive cancer from sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Amemori S, Yamano HO, Tanaka Y, Yoshikawa K, Matsushita HO, Takagi R, Harada E, Yoshida Y, Tsuda K, Kato B, Tamura E, Eizuka M, Sugai T, Adachi Y, Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Nakase H. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp showed rapid malignant transformation in the final 13 months. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:979-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yu-hu L, Lei-lei Z, Gui-quan C, Dong P, Jin C, Shi-hao, Z. The analysis of detection rate and risk factors of colorectal sessile serrated adenoma. Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2019;19 (1): 65-67. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Li QY, Xiao P, Ling TS, Sun YY, Luo LJ, Liang R, Deng ZJ, Situ WJ. [Detection of proximal serrated polyps:a single-center retrospective analysis]. Chinese Journal of Digestive Endoscopy. 2019;36 (2):86-90. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Ritsuno H, Shibuya T, Osada T, Mitomi H, Yao T, Watanabe S. Distinct endoscopic characteristics of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:590-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cassese G, Amendola A, Maione F, Giglio MC, Pagano G, Milone M, Aprea G, Luglio G, De Palma GD. Serrated Lesions of the Colon-Rectum: A Focus on New Diagnostic Tools and Current Management. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:9179718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A. Endoscopic diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3250-3259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 28. | Yamamoto S, Varkey J, Hedenström P. Acetic acid spray for better delineation of recurrent sessile serrated adenoma in the colon. VideoGIE. 2019;4:547-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tribonias G, Theodoropoulou A, Stylianou K, Giotis I, Mpitouli A, Moschovis D, Komeda Y, Manola ME, Paspatis G, Tzouvala M. Irrigating Acetic Acid Solution During Colonoscopy for the Detection of Sessile Serrated Neoplasia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:282-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kono Y, Higashi R, Mizushima H, Shimizu D, Katayama T, Kosaka M, Hirata I, Hirata T, Gotoda T, Miyahara K, Moritou Y, Kunihiro M, Nakagawa M, Ichimura K, Okada H. Usefulness of Acetic Acid Spray with Narrow-Band Imaging for Identifying the Margin of Sessile Serrated Lesions. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Suzuki Y, Ohata K, Matsuhashi N. Delineating sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with acetic acid spray for a more accurate piecemeal cold snare polypectomy. VideoGIE. 2020;5:519-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tadepalli US, Feihel D, Miller KM, Itzkowitz SH, Freedman JS, Kornacki S, Cohen LB, Bamji ND, Bodian CA, Aisenberg J. A morphologic analysis of sessile serrated polyps observed during routine colonoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1360-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Aoi K, Matsuura N, Nagai K, Matsui F, Ito T, Fujii M, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Tomita Y, Iishi H. Diagnostic features of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps on magnifying narrow band imaging: a prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Saito S, Tajiri H, Ikegami M. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum: Endoscopic features including image enhanced endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:860-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang Y, Ren YB, Yang XS, Huang YH, Zhang L, Li X, Bai P, Wang L, Fan X, Ding YM, Li HL, Lin XC. [Comparison of endoscopic features between colorectal sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with or without cytologic dysplasia and hyperplastic polyp]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;99:2214-2220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yamada M, Sakamoto T, Otake Y, Nakajima T, Kuchiba A, Taniguchi H, Sekine S, Kushima R, Ramberan H, Parra-Blanco A, Fujii T, Matsuda T, Saito Y. Investigating endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:108-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Uraoka T, Higashi R, Horii J, Harada K, Hori K, Okada H, Mizuno M, Tomoda J, Ohara N, Tanaka T, Chiu HM, Yahagi N, Yamamoto K. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic criteria characteristic of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:555-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kimura T, Yamamoto E, Yamano HO, Suzuki H, Kamimae S, Nojima M, Sawada T, Ashida M, Yoshikawa K, Takagi R, Kato R, Harada T, Suzuki R, Maruyama R, Kai M, Imai K, Shinomura Y, Sugai T, Toyota M. A novel pit pattern identifies the precursor of colorectal cancer derived from sessile serrated adenoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:460-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Takamaru H, Wu SYS, Saito Y. Endocytoscopy: technology and clinical application in the lower GI tract. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |