Published online May 24, 2022. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v13.i5.352

Peer-review started: December 25, 2021

First decision: March 16, 2022

Revised: March 29, 2022

Accepted: April 21, 2022

Article in press: April 21, 2022

Published online: May 24, 2022

Processing time: 149 Days and 13 Hours

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is a rare and distinct type of hepatocellular carcinoma that frequently presents in an advanced stage in younger patients with no underlying liver disease. Currently, there is a limited understanding of factors that impact outcomes in FL-HCC.

To characterize the survival of FL-HCC by age, race, and surgical intervention.

This is a retrospective study of The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. We identified patients with FL-HCC between 2000-2018 by using an ICD-O-3 site code C22.0 and a histology code 8171/3: Hepatocellular carcinoma, fibrolamellar. In addition, demographics, tumor characteristics, types of surgical procedure, stages, and survival data were obtained. We conducted three separate survival analyses by age groups; ≤ 19, 20-59, and ≥ 60-year-old, and race; White, Black, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific islanders (API), and surgical types; Wedge resection or segmental resection, lobectomy, extended lobectomy (lobectomy + locoregional therapy or resection of the other lobe), and transplant. The Chi-Square test analyzed categorical variables, and continuous variables were examined using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to compare survival. Multivariate analysis was done with Cox regression analysis.

We identified 225 FL-HCC patients with a mean age of 36.9. Overall median survival was 34 (95%CI: 27-41) mo. Patients ≤ 19-years-old had more advanced disease with positive lymph nodes status. However, they received more surgical interventions such as a wedge, segmental resection, lobectomy, extended lobectomy, and transplant. Survival for ≤ 19 was 85 (95%CI: 37-137) mo, age 20-59 was 29 (95%CI: 18-41) mo, and age ≥ 60 years was 12 (95%CI: 7-31) mo (P < 0.001). There were no differences in stage, lymph node status, metastasis status, and surgical treatment among races. The median survival were; Whites had 39 (95%CI: 29-63), Blacks 26 (95%CI: 5-92), Hispanics 31 (95%CI: 11-54), and APIs 28 (95%CI: 5-39) mo (P = 0.28). Of 225 patients, 111 FL-HCC patients had surgical procedures. Median survivals for a wedge or segmental resection was 112 (95%CI: 78-NA), lobectomy was 92 (95%CI: 57-NA), extended lobectomy was 54 (95%CI: 23-NA), and a transplant was 63 (95%CI: 20-NA) mo (P < 0.001). The median survival was better in patients who had surgical treatments regardless of lymph nodes or metastasis status (P < 0.001).

FL-HCC occurs in a primarily younger population, but survival can be prolonged despite the aggressive disease. There were no racial differences in the survival of FL-HCC; however, Asians with FL-HCC tended to be older than in other races. Surgical treatment provided better survival even in those patients with nodal disease or metastases. Although future studies are needed to explore other therapies for FL-HCC, surgical options should be considered in all cases of FL-HCC unless contraindicated.

Core Tip: Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is a rare and distinct type of hepatocellular carcinoma. Currently, there is limited data on survival associated with FL-HCC. This retrospective study based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database suggests a better survival of younger patients with FL-HCC, although they had aggressive diseases. This trend may be because they received more surgical interventions. There were no racial differences in survival for FL-HCC, which is seen in HCC. The patient who had wedge or segmental resection or lobectomy had better survival.

- Citation: Sempokuya T, Forlemu A, Azawi M, Silangcruz K, Khoury N, Ma J, Wong LL. Survival characteristics of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database study. World J Clin Oncol 2022; 13(5): 352-365

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v13/i5/352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v13.i5.352

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is a rare and distinct type of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with an estimated incidence of 0.02 per 100000 in the U.S., and it accounts for < 1% of all primary liver tumors[1-3]. It is often found in the younger patients without known underlying cirrhosis or hepatic dysfunction and may present with advanced stages[4,5]. The pathogenesis of FL-HCC remains unclear, and it has not been associated with alcohol intake or viral hepatitis infections[6]. HCC was thought to originate from mature hepatocytes[7]. However, recent studies have suggested that FL-HCC may be derived from neuroendocrine progenitors[1]. FL-HCC is a vascular tumor with significant fibrosis and a well-differentiated tumor[1,5]. On computed tomography scan, FL-HCC appears as a hypodense mass with arterial enhancement and calcifications[8]. FL-HCC patients may present with non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain and fullness, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting[5], or asymptomatic with tumors found incidentally[9].

As FL-HCC is a rare type of cancer, there are no specific guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in the United States to direct therapy. The majority of HCC clinical trials have excluded FL-HCC patients due to distinct disease progressions[10]. Therefore, treatment outcome with systemic therapy or immunotherapy has yet to be elucidated. A small study with 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy demonstrated an incomplete response to treatment[11]. In general, FL-HCC has better survival than the common type of HCC, likely because these patients are younger and in the absence of underlying liver disease, they are more likely to qualify for curative surgical procedures[12]. While treatment modalities vary based on the tumor stages and resectability, complete resection with regional lymphadenectomy has the longest survival[13]. In a study by Stipa et al[9], 28 patients with FL-HCC who underwent complete resection had a 5-year overall survival of 76%. However, advanced stage FL-HCC has poor prognosis with a median survival of fewer than 12 mo[7].

There is a limited understanding of disease characteristics and factors affecting the survival outcomes on FL-HCC due to disease rarity and lack of randomized control trials. Single institution or multicenter studies do not have enough cases to characterize FL-HCC survival. This study aimed to characterize the survival of FL-HCC by age, race, and surgical intervention using a larger population-based database.

The National Cancer Institute publishes population data on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, and research data was obtained through Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/) version 8.3.6[14]. SEER Registries contains population-based data on cancer incidence, characteristics, treatment, and mortality in select states in United States since 1973. Approximately 34.6% of all cancer cases in the United States population are included[15]. The SEER dataset utilized in this study is based on 18 states in United States and regions available to conduct survival analysis: Alaska Native Tumor Registry, California (San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Connecticut, Georgia (Atlanta, Greater Georgia, Rural Georgia), Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah and Washington (Seattle-Puget Sound) (more details are available at https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/terms.html). This study followed the SEER Research Data Use Agreement. As we utilized a publicly available, de-identified database, approval from an Institutional Review Board was not required to conduct this study.

We initially identified patients with FL-HCC between 2000-2018 by using an ICD-O-3 site code C22.0 and a histology code 8171/3: Hepatocellular carcinoma, fibrolamellar. Subsequently, we excluded patients from 2000-2003 and 2016-2018 due to the high number of missing data on demographic and disease-specific variables. Therefore, the years between 2004 and 2015 were included in this study. Additionally, one patient had duplicate data, so we used the variables with initial disease onset. Variables related to demographics data [age at the time of diagnosis, sex, race (Whites, Blacks, API, and Hispanics), living settings (population > 1 million and other), household income (< $55000, $55000-70000, and > $70000)], staging by American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition[16] (categorized into stage I, II, III, IV, and unknown), tumor characteristics (size, metastasis status, lymph node status), surgical treatment modality (wedge or segmental resection, lobectomy, extended lobectomy (lobectomy + locoregional therapy or resection of the other lobe), transplant, and None (Including a small number of patients who had locoregional therapy and unspecified surgery), and survival data were obtained. Data on chemotherapy and interventional therapy was not included due to limitations acknowledged by the SEER database to avoid data inaccuracy.

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). The Chi-Square test was used to compare categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test compared continuous variables without normal distributions of two groups and Druska-Wallis for more than two groups. Survival analysis was done by using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Three separate analyses were done: Analysis by age groups, race, and surgical procedures. For age group analysis, patients were divided into three groups: ≤ 19, 20-59, and ≥ 60-year-old. For race analysis, we divided into four racial groups: White, Black, API, and Hispanic. For analysis of surgical procedures, we separated into five groups: Wedge resection or segmental resection, lobectomy, extended lobectomy, transplant, and none. For additional survival analysis, we separate the patients based on positive lymph nodes or metastasis status (N1M0, N1M1, N0M1, NxM1: NM+) vs negative (N0M0, NxM0, N0Mx, NxMx: NM-). We then stratified by surgical status vs. no surgery or locoregional therapy. We conducted multivariate Cox regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Jihyun Ma from the Department of Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

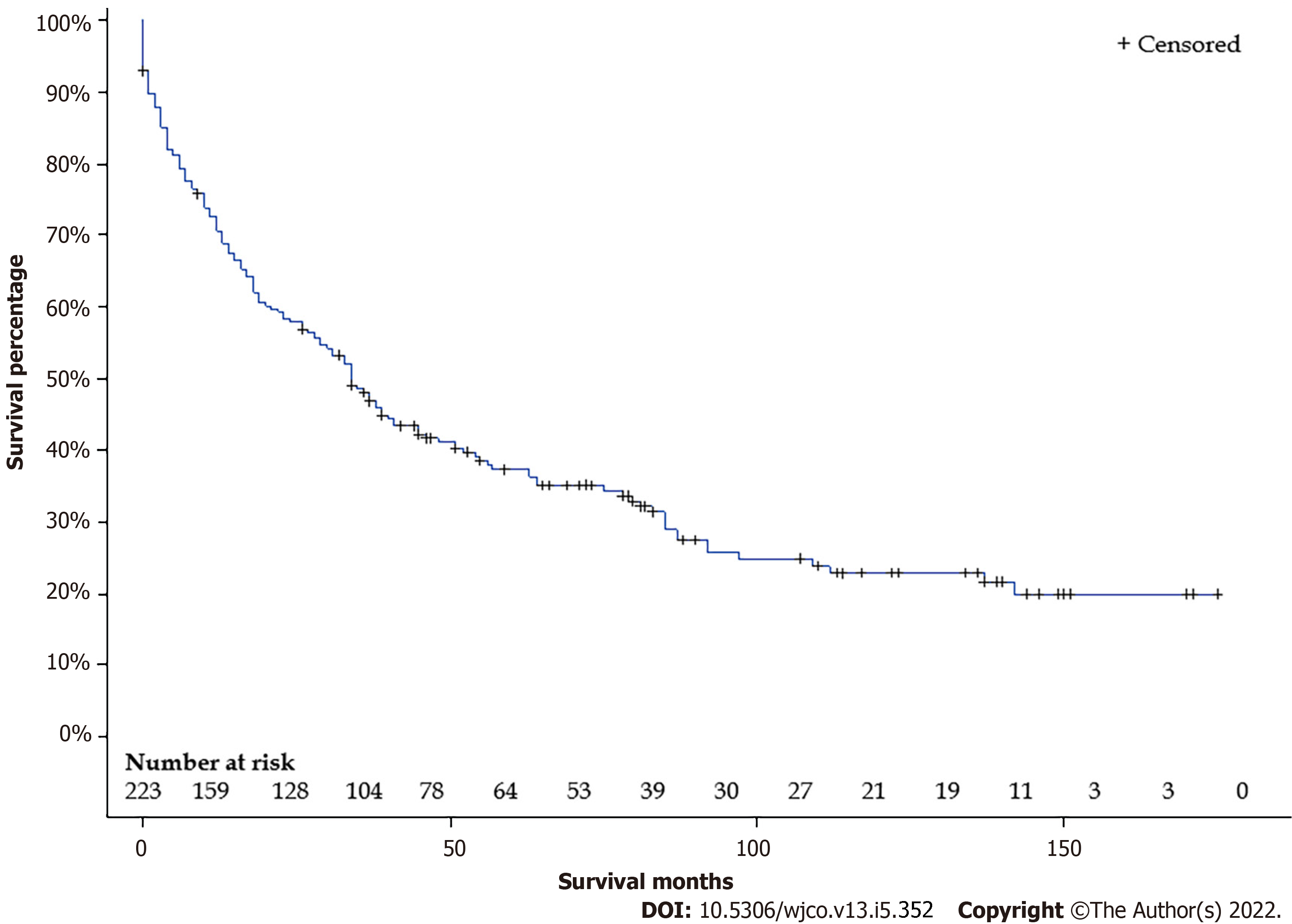

We initially identified 339 FL-HCC patients between 2000 and 2018. After excluding 114 patients due to missing data, 225 FL-HCC patients were included in our study. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 36.9 years, with a median age of 27 years. (Interquartile range: 19-56). One hundred fourteen (62.7%) patients were male. Sixty-five (28.9%) had stage I, 18 (8.0%) had stage II, 61 (27.1%) had stage III, 61 (27.1%) had stage IV, and 20 (89%) had unknown stages. Thirty-nine patients (17.8%) had a wedge or segmental resection, 42 (19.2%) had a lobectomy, 11 (5.0%) had an extended lobectomy, 19 (8.7%) underwent live transplant, 108 (49.3) did not have any surgical intervention. Overall median survival was 34 (95%CI: 27-41) mo (Figure 1). Overall 5-years survival rate was 37.3 ± 3.3%.

| Factor | Group | Alive (%) | P value | < 20 | 20-59 | 60+ | P value | |

| n (%) | 225 | 67 (29.8) | 62 (27.5) | 114 (50.7) | 49 (21.8) | |||

| Median age (IQR) | 27 (19-56) | 15.5 (13-17) | 28.5 (23-44) | 69.0 (65-76) | ||||

| Male (%) | 141 (62.7) | 42 (29.8) | 0.99 | 33 (23.4) | 74 (52.5) | 34 (24.1) | 0.17 | |

| Race (%) | White | 124 (55.1) | 39 (31.5) | 0.66 | 34 (27.4) | 67 (54.3) | 23 (18.6) | 0.07 |

| Black | 27 (12.0) | 8 (29.6) | 6 (22.2) | 16 (59.3) | 5 (18.5) | |||

| API | 22 (9.8) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) | 9 (40.9) | 10 (45.5) | |||

| Hispanic | 52 (23.1) | 16 (30.8) | 19 (36.5) | 22 (42.3) | 11 (21.2) | |||

| Household income (%) | < $55000 | 55 (24.4) | 20 (36.4) | 0.47 | 16 (29.1) | 32 (58.2) | 7 (12.7) | 0.37 |

| $55000-70000 | 88 (39.1) | 24 (27.8) | 26 (29.6) | 40 (45.5) | 22 (25.0) | |||

| > $70,000 | 82 (36.4) | 23 (28.0) | 20 (24.4) | 42 (51.2) | 20 (24.4) | |||

| Living settings (%) | Population > 1 million | 144 (61.0) | 36 (25.0) | 0.04 | 38 (26.4) | 71 (49.3) | 35 (24.3) | 0.47 |

| Other | 81 (36.0) | 31 (38.3) | 24 (29.6) | 43 (53.1) | 14 (17.3) | |||

| Stages (%) | I | 65 (28.9) | 32 (49.2) | < 0.001 | 13 (20) | 29 (44.6) | 23 (35.4) | 0.02 |

| II | 18 (8.0) | 8 (44.4) | 7 (38.9) | 7 (38.9) | 4 (22.2) | |||

| III | 61 (27.1) | 19 (31.1) | 20 (32.8) | 32 (25.5) | 9 (14.8) | |||

| IV | 61 (27.1) | 2 (3.3) | 20 (32.8) | 34 (55.7) | 7 (11.5) | |||

| Unknown | 20 (8.9) | 6 (30.0) | 2 (10.0) | 12 (60.0) | 6 (30.0) | |||

| Lymph Node status (%) | N0 | 143 (63.6) | 52 (36.4) | 0.009 | 35 (24.5) | 68 (47.6) | 40 (28.0) | 0.004 |

| N1 | 60 (26.7) | 13 (21.7) | 24 (40.0) | 32 (53.3) | 4 (6.7) | |||

| Nx | 22 (9.78) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (13.6) | 14 (63.6) | 5 (22.7) | |||

| Metastasis status (%) | M0 | 154 (68.4) | 64 (41.6) | < 0.001 | 41 (26.6) | 74 (48.05) | 39 (25.3) | 0.16 |

| M1 | 61 (27.1) | 2 (3.3) | 20 (32.8) | 34 (55.7) | 7 (11.5) | |||

| Mx | 10 (4.4) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (30.0) | |||

| Surgery (%) | Wedge/segmental resection | 39 (17.8) | 23 (59.0) | < 0.001 | 15 (38.5) | 17 (43.6) | 7 (18.0) | < 0.001 |

| Lobectomy | 42 (19.2) | 21 (50.0) | 23 (43.4) | 23 (54.8) | 3 (7.1) | |||

| Extended lobectomy | 11 (5.0) | 6 (54.5) | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0) | |||

| Transplant | 19 (8.7) | 7 (36.8) | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | 0 (0) | |||

| None | 108 (49.3) | 10 (9.3) | 18 (16.7) | 54 (50.0) | 36 (33.3) | |||

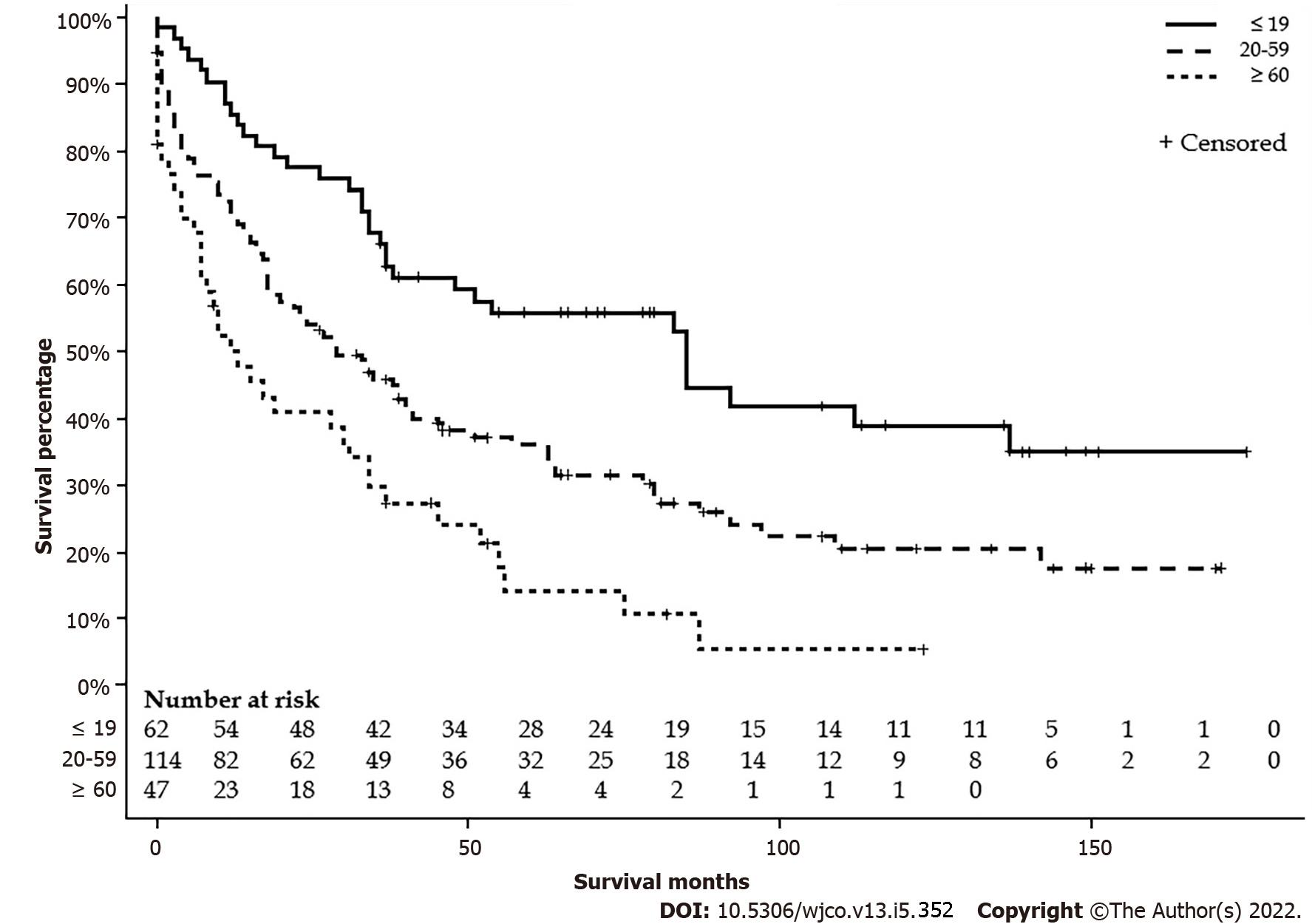

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics by age group. Sixty-two (27.5%) patients were age ≤ 19 years, 114 (50.7%) patients were between 20 to 59 years, and 49 (21.8%) patients were age ≥ 60 years. Patients ≤ 19-year-old had more nodal involvement and higher stages. A higher proportion of patients ≤ 19-year-old received the surgical intervention and none of the patients ≥ 60-year-old received extended lobectomy or transplant. There were no differences in sex, race, living settings, household income, and metastasis status. Detailed characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median survival for ≤ 19 years was 85 mo (95%CI: 37-137), 20-59 years was 29 mo (95%CI: 18-41), and ≥ 60 years was 12 (95%CI: 7-31) mo (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). The five-year survival rate for patients ≤ 19-year-old was 55.3 (6.5%), 20-59-year-old was 35.8 (4.6%), and ≥ 60-year-old was 14.6 (5.9%).

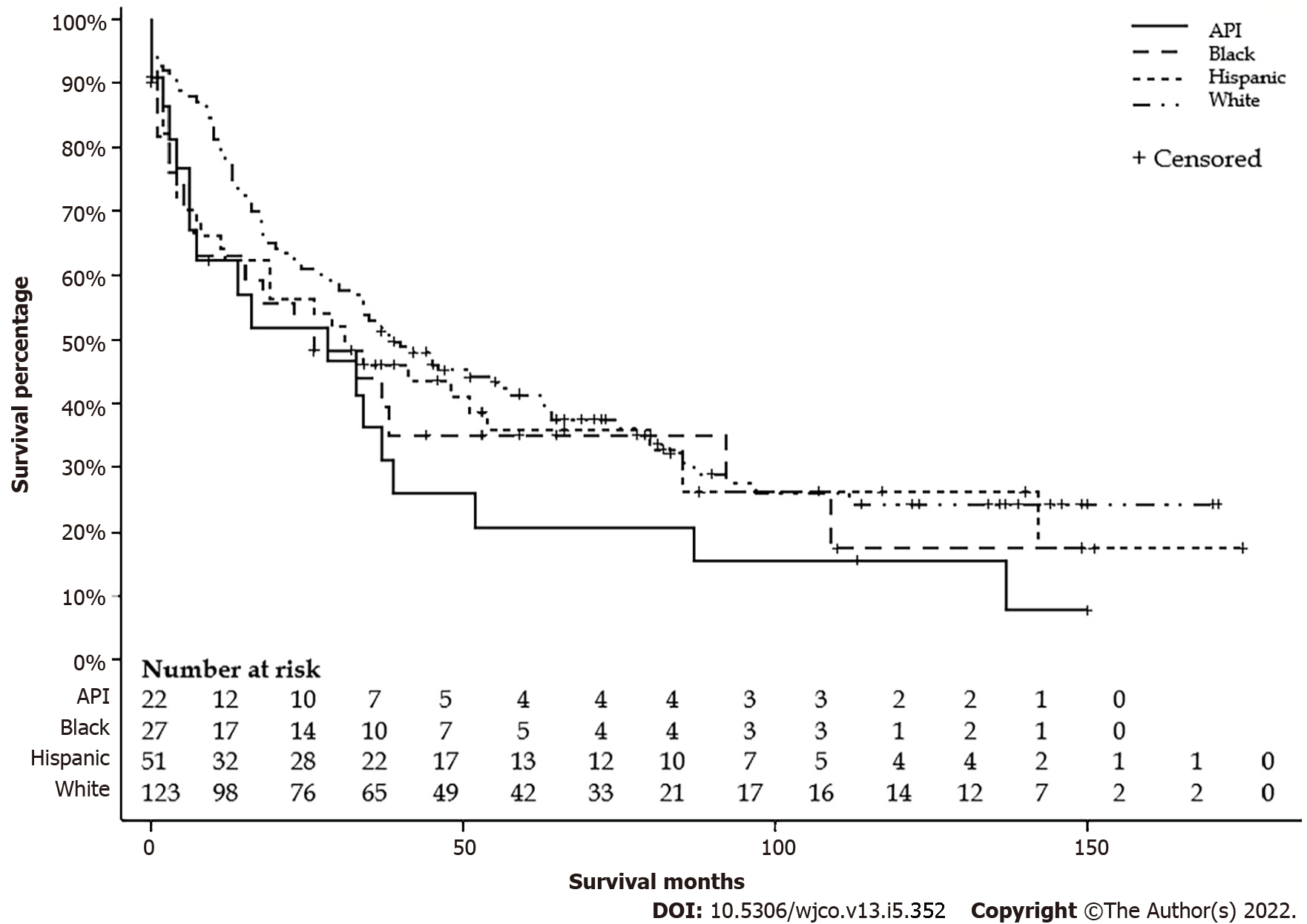

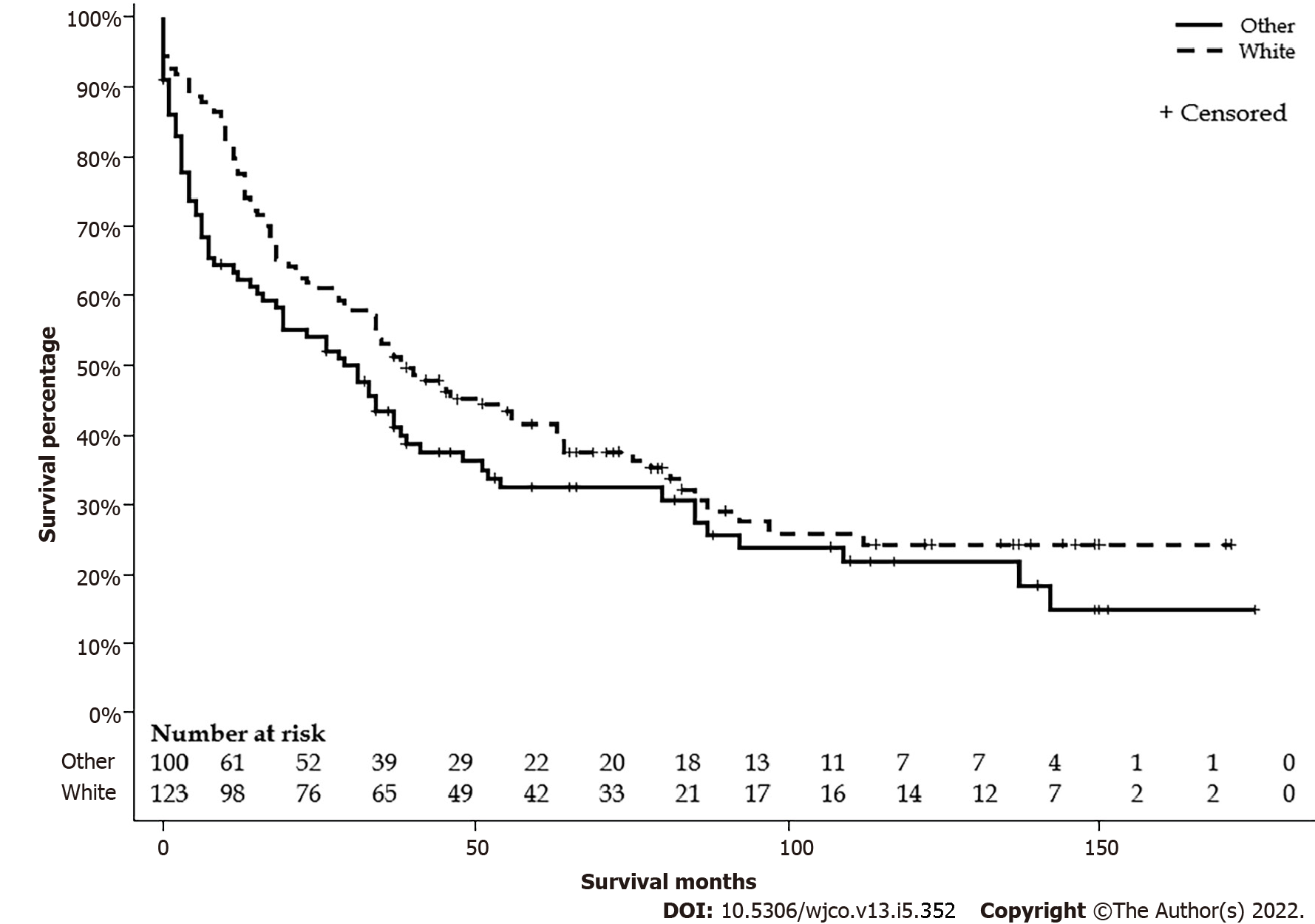

There were 124 (55.1%) Whites, 52 (23.1%) Hispanics, 27 (12.0%) Blacks, and 22 (9.8%) APIs. Mean ages were 35.9, 37.2, 33.6, and 49.5 years, respectively. There were no differences in the distribution between the age groups or sex. APIs lived in the area with a higher median household income, and Blacks lived in the area with a lower median household income. A higher proportion of Whites lives in areas with a population < 1 million. There were no differences in stages, lymph node status, metastasis status, and surgical treatment. Detailed characteristics are listed in Table 2. The median survival differences by race were not significant: Whites had 39 (95%CI: 29-63), Blacks 26 (95%CI: 5-92), APIs 28 (95%CI: 6-39), and Hispanics 31 (95%CI: 11-54) mo (P = 0.28) (Figure 3). Furthermore, Whites had similar median survival compared to all other non-White races combined (39 vs 29 mo, P = 0.11) (Figure 4).

| Factor | Group | Total | White | Black | API | Hispanic | P value |

| n (%) | 225 | 124 (55.1) | 27 (12.0) | 22 (9.8) | 52 (23.1) | ||

| Median age (IQR) | 27 (19-56) | 27.0 (19-54.5) | 32.0 (21-55) | 52.0 (27-70) | 23.0 (17-53.5) | 0.04 | |

| Age groups (%) | ≤ 19 | 62 (27.5) | 34 (54.8) | 6 (9.7) | 3 (4.8) | 19 (30.7) | 0.07 |

| 20-59 | 114 (50.7) | 67 (58.8) | 16 (14.0) | 9 (7.9) | 22 (19.3) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 49 (21.8) | 23 (46.9) | 5 (10.2) | 10 (20.4) | 11 (22.5) | ||

| Male (%) | 141 (62.7) | 75 (53.2) | 18 (12.8) | 14 (9.9) | 34 (24.1) | 0.89 | |

| Household income (%) | < $55000 | 55 (24.4) | 34 (61.8) | 10 (18.2) | 1 (1.8) | 10 (18.2) | 0.02 |

| $55000-70000 | 88 (39.1) | 42 (47.7) | 6 (6.8) | 12 (13.6) | 28 (31.8) | ||

| > $70000 | 82 (36.4) | 48 (58.5) | 11 (13.4) | 9 (11.0) | 14 (17.1) | ||

| Living settings (%) | Population > 1 million | 144 (61.0) | 68 (47.2) | 21 (14.6) | 18 (12.5) | 37 (25.7) | 0.01 |

| Other | 81 (36.0) | 56 (69.1) | 6 (7.4) | 4 (4.9) | 15 (18.5) | ||

| Stages (%) | I | 65 (28.9) | 38 (58.5) | 7 (10.8) | 7 (10.8) | 13 (20.0) | 0.71 |

| II | 18 (8.0) | 11 (61.1) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (16.7) | ||

| III | 61 (27.1) | 30 (49.2) | 7 (11.5) | 3 (4.9) | 21 (34.4) | ||

| IV | 61 (27.1) | 34 (55.7) | 7 (11.5) | 8 (13.1) | 12 (19.7) | ||

| Unknown | 20 (8.9) | 11 (55.0) | 4 (20.0) | 2 (10.0) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Lymph Node status (%) | N0 | 143 (63.6) | 74 (51.8) | 16 (11.2) | 17 (11.9) | 36 (25.2) | 0.11 |

| N1 | 60 (26.7) | 38 (63.3) | 5 (8.3) | 3 (5.0) | 14 (23.3) | ||

| Nx | 22 (9.78) | 12 (54.6) | 6 (27.3) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Metastasis status (%) | M0 | 154 (68.4) | 85 (55.2) | 18 (11.7) | 12 (7.8) | 39 (25.3) | 0.63 |

| M1 | 61 (27.1) | 34 (55.7) | 7 (11.5) | 8 (13.1) | 12 (19.7) | ||

| Mx | 10 (4.4) | 5 (50.0) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Surgery (%) | Wedge/segmental resection | 39 (17.8) | 28 (71.8) | 2 (5.1) | 3 (7.7) | 6 (15.4) | 0.28 |

| Lobectomy | 42 (19.2) | 25 (59.5) | 6 (14.3) | 3 (7.1) | 8 (19.1) | ||

| Extended lobectomy | 11 (5.0) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 5 (45.5) | ||

| Transplant | 19 (8.7) | 12 (63.2) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| None | 108 (49.3) | 49 (45.4) | 17 (15.7) | 13 (12.0) | 29 (26.9) |

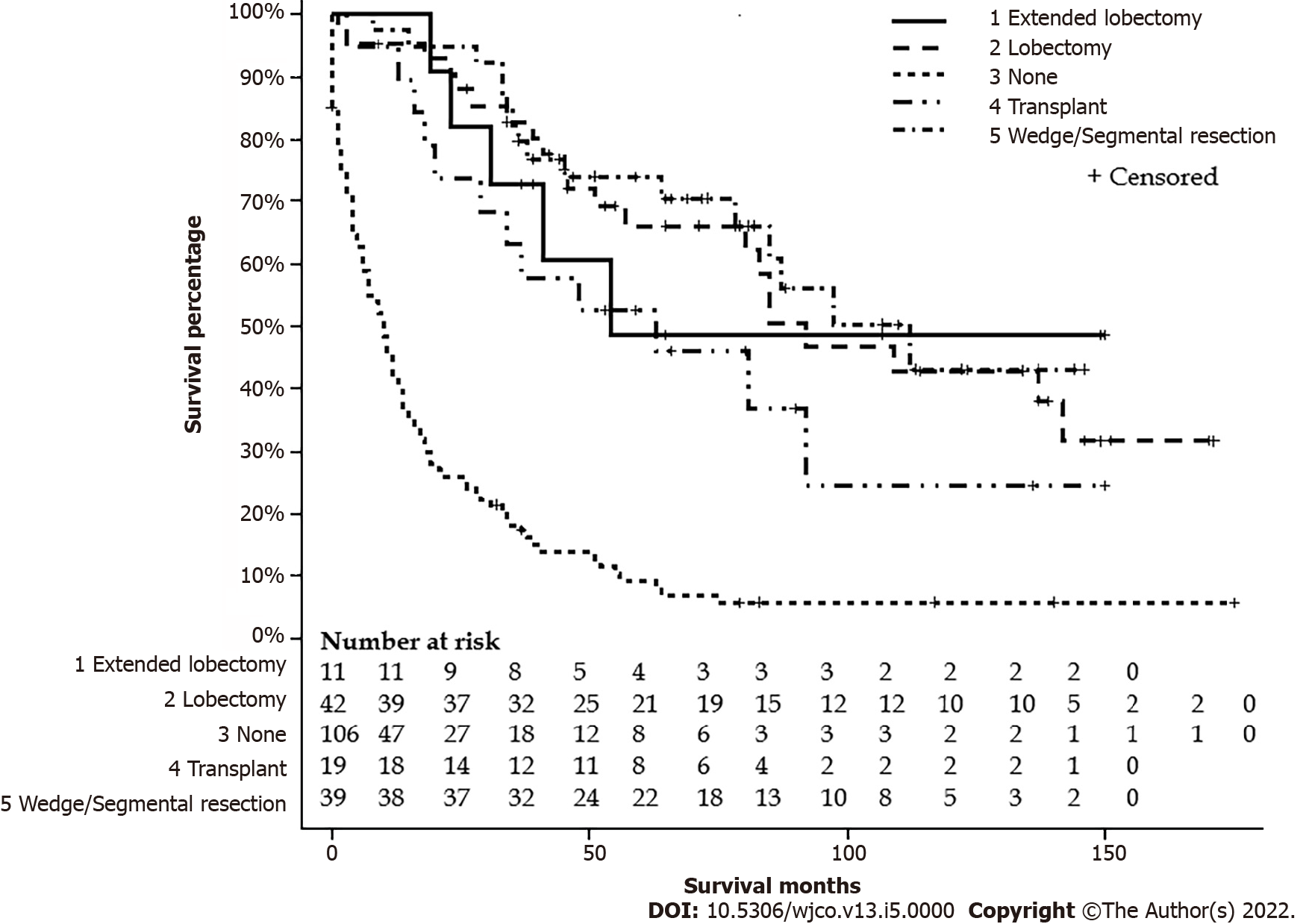

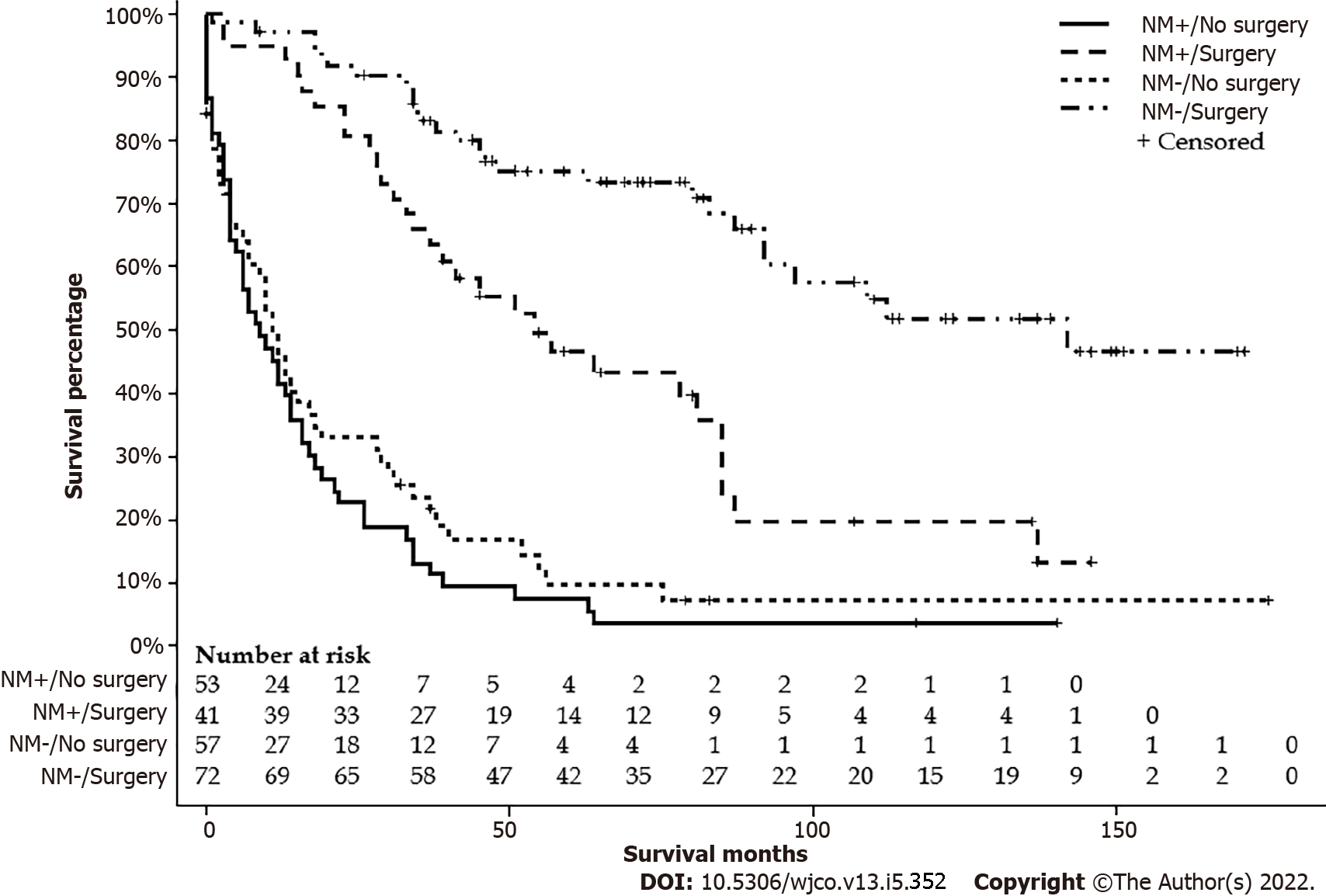

After excluding six patients with missing data on surgery status, one hundred eleven FL-HCC patients had surgical intervention. One hundred and eight patients did not have a surgical intervention or received life review therapy, 42 underwent liver transplantation, 19 had wedge or segmental liver resection, 39 had a lobectomy, and 11 had extended lobectomy. Age groups, stages, lymph nodes status, metastasis status, and tumor size had a significant difference among types of surgical intervention. Detailed characteristics are listed in Table 3. The median survivals for a wedge or segmental resection were 112 (78-NA), lobectomy was 92 (57-NA), extended lobectomy was 54 (23-NA), the transplant was 63 (20-NA), and none was 10 (6-13) mo (P < 0.001) (Figure 5). The median survival for NM+/no surgery was 9 (4-14) mo, NM+/surgery was 54 (34-85) mo, NM-/no surgery was 11 (6-17) mo, and NM-/surgery was 142 (92-NA) mo (P < 0.001) (Figure 6).

| Factor | Group | None | Transplant | Wedge or segmental resection | Lobectomy | Extended lobectomy | P value |

| n | Total 219 | 108 | 19 | 39 | 42 | 11 | |

| Alive | Total 67 | 10 (9.3) | 7 (36.8) | 23 (59.0) | 21 (50.0) | 6 (54.6) | < 0.001 |

| Age group (%) | ≤ 19 | 18 (16.7) | 6 (31.6) | 15 (38.5) | 16 (38.1) | 7 (63.6) | < 0.001 |

| 20-59 | 54 (50.0) | 13 (68.4) | 17 (43.6) | 23 (54.8) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 36 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (18.0) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sex (%) | Male | 70 (64.8) | 12 (63.2) | 27 (69.2) | 21 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) | 0.43 |

| Stages (%) | I | 22 (20.4) | 4 (21.1) | 19 (48.7) | 15 (35.7 ) | 2 (18.2) | < 0.001 |

| II | 3 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 8 (20.5) | 5 (11.9) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| III | 24 (22.2) | 10 (52.6) | 9 (23.1) | 13 (31.0) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| IV | 43 (39.8) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (7.7) | 8 (19.1) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Unknown | 16 (14.8) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Race (%) | API | 13 (12.0) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (7.7) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0.28 |

| Black | 17 (15.7) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (5.1) | 6 (14.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hispanic | 29 (26.9) | 4 (21.1) | 6 (15.4) | 8 (19.1) | 5 (45.5) | ||

| White | 49 (45.4) | 12 (63.2) | 28 (71.8) | 25 (59.5) | 5 (45.5) | ||

| Income (%) | < $55000 | 29 (26.9) | 3 (15.8) | 12 (30.8) | 8 (19.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0.22 |

| $55000-70000 | 41 (38.0) | 8 (42.1) | 15 (38.5) | 13 (31.0) | 8 (72.7) | ||

| > $70000 | 38 (35.2) | 8 (42.1) | 12 (30.8) | 21 (50.0) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Lymph nodes status (%) | N0 | 64 (59.3) | 12 (63.2) | 32 (82.1) | 24 (57.1) | 6 (54.6) | 0.007 |

| N1 | 25 (23.2) | 6 (31.6) | 7 (18.0) | 17 (40.5) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| Nx | 19 (17.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0(0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Metastasis status (%) | M0 | 56 (52.9) | 15 (79.0) | 36 (92.3) | 34 (81.0) | 8 (72.7) | < 0.001 |

| M1 | 43 (39.8) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (7.7) | 8 (19.1) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Mx | 9 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Population (%) | ≥ 1 million | 76 (70.4) | 13 (68.4) | 21 (53.9) | 24 (57.1) | 7 (63.6) | 0.32 |

| Others | 32 (29.7) | 6 (31.6) | 18 (46.2) | 18 (42.9) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| Size (%) | ≤ 50 mm | 18 (16.7) | 1 (5.3) | 12 (30.8) | 6 (14.3) | 1 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| 51-100 mm | 25 (23.2) | 5 (26.3) | 15 (38.5) | 14 (33.3) | 3 (27.3) | ||

| ≥ 100 mm | 37 (34.3) | 11 (57.9) | 10 (25.6) | 21 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) | ||

| Unknown | 28 (25.9) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) |

Median survival months for stage I was 97 (95%CI: 34-NA), stage II was 87 (95%CI: 35-NA), stage III was 45 (95%CI: 29-63), stage IV was 14 (95%CI: 8-21), and the unknown stage was 18 (95%CI: 7-75) mo. The five-year survival rate for stage I was 53.6 ± 6.4%, stage II was 70.1 ± 11.2%, stage III was 37.6 ± 6.7%, stage IV was 13.1 ± 4.3%, and the unknown stage was 31.3 ± 10.9%.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis included the following variables: age groups (compared to age ≤ 19), sex (compared to female), race (compared to White), income (compared to < $55000), surgery (compared to no surgery or locoregional therapy), population (compared to other), tumor size (compared to ≤ 50 mm), lymph node status (compared to N0), and metastasis status (compared to M0). This model excluded two patients with unknown surgical status. Due to the interaction with tumor size, lymph node status, and metastasis status, the stage was excluded from the model. This model showed that only Nx had a significant hazard ratio of 0.11 ± 1.37. Table 4 summarizes the result.

| Hazard ratio | Standard error | P value | ||

| Age group (%) | 20-59 | 0.931 | 0.327 | 0.83 |

| ≥ 60 | 2.554 | 0.557 | 0.09 | |

| Sex (%) | Male | 1.169 | 0.288 | 0.59 |

| Race (%) | API | 0.624 | 0.581 | 0.42 |

| Black | 2.296 | 0.461 | 0.07 | |

| Hispanic | 0.9 | 0.368 | 0.78 | |

| Income (%) | $55000-70000 | 1.044 | 0.368 | 0.91 |

| > $70000 | 0.644 | 0.345 | 0.2 | |

| Sugery | Surgery | 1.465 | 0.472 | 0.42 |

| Population (%) | ≥ 1 million | 1.209 | 0.287 | 0.51 |

| Size (%) | ≥ 100 mm | 1.104 | 0.44 | 0.82 |

| 51-100 mm | 1.233 | 0.426 | 0.62 | |

| Unknown | 3.196 | 0.646 | 0.07 | |

| Lymph nodes (%) | N1 | 1.503 | 0.39 | 0.3 |

| Nx | 0.107 | 0.993 | 0.02 | |

| Metastasis status (%) | M1 | 0.301 | 0.782 | 0.13 |

| Mx | 7.503 | 1.366 | 0.14 |

FL-HCC is a rare and unique type of HCC, and it commonly affects younger patients without underlying cirrhosis. Due to the rare nature of FL-HCC, disease characteristics and survival of FL-HCC by age, race, and surgical intervention remain scarce. To our knowledge, this is one of the larger population-based studies on FL-HCC obtained from a nationwide cancer registry, including detailed tumor characteristics. The study highlights and provides a better understanding of FL-HCC survival based on age, race, and surgical interventions at the population level. Overall median survival of patients with FL-HCC in this study was 34 mo, similar to that of other studies[2,17]. Our median survival was lower than the 75 mo obtained by Mayo and colleagues in 2014, analyzing SEER data from 1986 to 2008[12]. This difference is due to the fact that they only included surgically managed FL-HCC. Besides, their patients were younger (mean age: 25 vs 36 years) than ours, and they had a smaller sample size of FL-HCC (90 patients) compared to ours. In effect, younger age at diagnosis has been associated with better survival[18,19]. Also, FL-HCC was only established as a separate diagnosis in 1986, and there may have been a few years of transition before providers consistently coded FL-HCC as a distinct entity[12].

The median age of patients in our study was 36 years, similar to that of other studies[18,20]. FL-HCC is known to have a predilection to develop in young patients[18]; hence it was no surprise that the majority of patients with FL-HCC in our study were younger. Also, younger patients (≤ 19 years) in our study with FL-HCC were more likely to have advanced stags with positive lymph nodes status and were more often treated with resection or transplantation as described in previous studies[12,18]. These studies have suggested FL-HCC has a better prognosis because it primarily affects children and teens and because of the many surgical therapies available (wedge, segmental resection, lobectomy, and transplant) for this patient population, unlike with HCC[12]. Likewise, young patients with FL-HCC are usually otherwise healthy, lack liver cirrhosis, and have high resectability rates with low rates of surgical complications[21,22]. Pinna et al[22] in 1997 reported survival of 66% at five years despite 90% of FL-HCC patients presenting with stage IV disease.

Patients with FL-HCC in our study were overwhelmingly non-Hispanic whites, findings similar to the study by El-Serag et al[18] in 2004. The rates of FL-HCC were not significantly different among Whites, Blacks, APIs, and Hispanics in our study, unlike with HCC patients, where incidence rates and prognosis vary with racial backgrounds[18,23]. APIs were older than others races in our study. Notably, there were no differences in tumor characteristics and surgical treatment by race. Also, survival rates of FL-HCC were similar across racial groups in our study; although there was a non-significant trend for survival in Whites to be higher than in non-Whites, behaving like findings seen with HCC patients, where non-Whites have lower survival rates[23]. On the other hand, some studies have found the Whites and female gender to be negative prognostic factors after surgery[24]. However, these findings have remained controversial[18,25]. Racial disparities observed in HCC patients are thought to be related to etiological and socio-demographic factors[26]. Our findings suggest that these factors may not play a role in FL-HCC survival as we found no significant racial disparities.

Surgical resection has remained the treatment of choice for FL-HCC given the younger age of these patients, localized disease, and lack of underlying liver cirrhosis[24,27]. Most of these surgeries were segmental surgeries and lobectomies, with fewer cases of liver transplantation. In our study, the majority of FL-HCC patients who had surgical intervention were young and had earlier stages. Nineteen (17.1%) patients underwent liver transplantation, and 11 (9.9%) had extended lobectomy, with many having an advanced disease. Our findings are similar to those of Eggert et al[25], 2013 and Assi et al[20], 2020. The survival in our study increased with surgery and was highest in FL-HCC patients who had a wedge or segmental hepatic resection with 112 mo. Previous studies have demonstrated age and tumor resectability to be independent predictors of survival in FL-HCC patients[2,19,20]. In effect, having normal underlying liver parenchyma may allow for more aggressive and complete resections, decreasing the risk for recurrence. Currently, there is a paucity of data on aggressive surgical intervention in the setting of extended disease. Our study also highlights the importance of surgical treatment regardless of lymph nodes or metastasis status. As we do not have randomized clinical trials to see the effectiveness of systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy to treat FL-HCC, surgical treatment may reduce tumor burden for curative or palliative intent.

Although this study included a large number of FL-HCC patients, there are several limitations to this study. Due to the nature of the SEER database, there is no information about comorbid medical conditions, laboratory data, or underlying liver disease, which may affect survival. One-third of the cases needed to be excluded due to inadequate information. As this is a registry study, we cannot account for errors and variations in reporting from the many coders required to acquire this data. Furthermore, the generalizability of this study may be limited as the SEER database includes select states and regions in United States. Finally, as FL-HCC is often diagnosed at an advanced stage in young, otherwise healthy patients, there may be a lead time bias when interpreting survival.

This study demonstrated a better survival of younger patients with FL-HCC despite the presence of aggressive diseases. There were no racial differences in survival for FL-HCC, which is typically seen in HCC. Surgical treatment provided better survival even in the face of nodal disease or metastases. Until more definitive data on locoregional therapy and systemic therapy can be elucidated, all patients with FL-HCC should be strongly considered for surgical intervention. Future studies will also be necessary to identify genetic markers for the population at risk for FL-HCC to enhance earlier detection.

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is a rare and distinct type of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Due to its rare nature, there is a limited understanding of factors affecting the survival outcomes.

This study aims to characterize the survival of FL-HCC by age, race, and surgical intervention.

FL-HCC patients were retrospectively identified with The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. We conducted three separate survival analyses by age groups; ≤ 19, 20-59, and ≥ 60-year-old, and race; White, Black, Asian and Pacific Islanders (API), and Hispanic and surgical types; Wedge resection or segmental resection, lobectomy, extended lobectomy (lobectomy + locoregional therapy or resection of the other lobe), and transplant.

We identified 225 FL-HCC patients. Overall median survival was 34 (95%CI: 27-41) mo. Patients ≤ 19-year-old had more advanced disease with positive lymph nodes status. However, they received more surgical interventions. Survival months for ≤ 19 was 85 (95%CI: 37-137), 20-59 was 29 (95%CI: 18-41), and ≥ 60 was 12 (95%CI: 7-31) mo (P < 0.001). APIs lived in the area with a higher median household income, and Blacks lived in the area with a lower median household income. There were no differences in stages, lymph node status, metastasis status, and surgical treatment. Whites had 39 (95%CI: 29-63), Blacks 26 (95%CI: 5-92), Hispanics 31 (95%CI: 11-54), and APIs 28 (95%CI: 5-39) mo (P = 0.28). Of 225 patients, 111 FL-HCC patients had surgical procedures. Median survivals for a wedge or segmental resection was 112 (95%CI: 78-NA), lobectomy was 92 (95%CI: 57-NA), extended lobectomy was 54 (95%CI: 23-NA), and a transplant was 63 (95%CI: 20-NA) mo (P < 0.001). The median survival was better in patients who had surgical treatments regardless of lymph nodes or metastasis status (P < 0.001).

This study demonstrated a better survival of younger patients with FL-HCC, although they had aggressive diseases. There were no racial differences in survival for FL-HCC, which is seen in HCC. Surgical treatment provided better survival regardless of advanced disease.

This study can help healthcare professionals to guide FL-HCC patients about the outcome, especially after the surgical intervention. Further prospective studies are needed to elucidate in the era of personalized cancer therapy.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Casanova Rituerto D, Spain; Elkady N, Egypt; Fakhradiyev I, Kazakhstan; Gursel B, Turkey; Ling Q, China; Xu HT, China S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Malouf GG, Job S, Paradis V, Fabre M, Brugières L, Saintigny P, Vescovo L, Belghiti J, Branchereau S, Faivre S, de Reyniès A, Raymond E. Transcriptional profiling of pure fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma reveals an endocrine signature. Hepatology. 2014;59:2228-2237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mavros MN, Mayo SC, Hyder O, Pawlik TM. A systematic review: treatment and prognosis of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:820-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Paradis V. Histopathology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2013;190:21-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu S, Chan KW, Wang B, Qiao L. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2617-24; quiz 2625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lafaro KJ, Pawlik TM. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: current clinical perspectives. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2015;2:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin CC, Yang HM. Fibrolamellar Carcinoma: A Concise Review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1141-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 3867] [Article Influence: 966.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Do RK, McErlean A, Ang CS, DeMatteo RP, Abou-Alfa GK. CT and MRI of primary and metastatic fibrolamellar carcinoma: a case series of 37 patients. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20140024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stipa F, Yoon SS, Liau KH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica M, Abou-Alfa G, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP. Outcome of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1331-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rimassa L, Personeni N, Czauderna C, Foerster F, Galle P. Systemic treatment of HCC in special populations. J Hepatol. 2021;74:931-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chakrabarti S, Tella SH, Kommalapati A, Huffman BM, Yadav S, Riaz IB, Goyal G, Mody K, Borad M, Cleary S, Smoot RL, Mahipal A. Clinicopathological features and outcomes of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:554-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mayo SC, Mavros MN, Nathan H, Cosgrove D, Herman JM, Kamel I, Anders RA, Pawlik TM. Treatment and prognosis of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a national perspective. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:196-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McAteer JP, Goldin AB, Healey PJ, Gow KW. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: epidemiology and the impact of regional lymphadenectomy on surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:2194-2201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | SEER*Stat Database: Incidence-SEER Research Data, 18 Registries, Nov 2019 Sub (2000-2017)-Linked To County Attributes-Time Dependent (1990-2017) Income/Rurality, 1969-2018 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2020, based on the November 2019 submission. [cited 2021 Dec 25]. Database: Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Available from: www.seer.cancer.gov. |

| 15. | Mohanty S, Bilimoria KY. Comparing national cancer registries: The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:629-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Greene F, Page D, Fleming I, Fritz A, Balch C, Haller D, Morrow M; American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. |

| 17. | Lemekhova A, Hornuss D, Polychronidis G, Mayer P, Rupp C, Longerich T, Weiss KH, Büchler M, Mehrabi A, Hoffmann K. Clinical features and surgical outcomes of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective analysis of a single-center experience. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Is fibrolamellar carcinoma different from hepatocellular carcinoma? Hepatology. 2004;39:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moreno-Luna LE, Arrieta O, García-Leiva J, Martínez B, Torre A, Uribe M, León-Rodríguez E. Clinical and pathologic factors associated with survival in young adult patients with fibrolamellar hepatocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Assi HA, Mukherjee S, Machiorlatti M, Vesely S, Pareek V, Hatoum H. Predictors of Outcome in Patients With Fibrolamellar Carcinoma: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:847-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3241] [Cited by in RCA: 3282] [Article Influence: 149.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pinna AD, Iwatsuki S, Lee RG, Todo S, Madariaga JR, Marsh JW, Casavilla A, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Treatment of fibrolamellar hepatoma with subtotal hepatectomy or transplantation. Hepatology. 1997;26:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Barzi A, Zhou K, Wang S, Dodge JL, El-Khoueiry A, Setiawan VW. Etiology and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in an Ethnically Diverse Population: The Multiethnic Cohort. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kassahun WT. Contemporary management of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis, treatment, outcome, prognostic factors, and recent developments. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Eggert T, McGlynn KA, Duffy A, Manns MP, Greten TF, Altekruse SF. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in the USA, 2000-2010: A detailed report on frequency, treatment and outcome based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:351-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xu L, Kim Y, Spolverato G, Gani F, Pawlik TM. Racial disparities in treatment and survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2016;5:43-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Njei B, Konjeti VR, Ditah I. Prognosis of Patients With Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma Versus Conventional Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2014;7:49-54. [PubMed] |