INTRODUCTION

Introduction and epidemiology

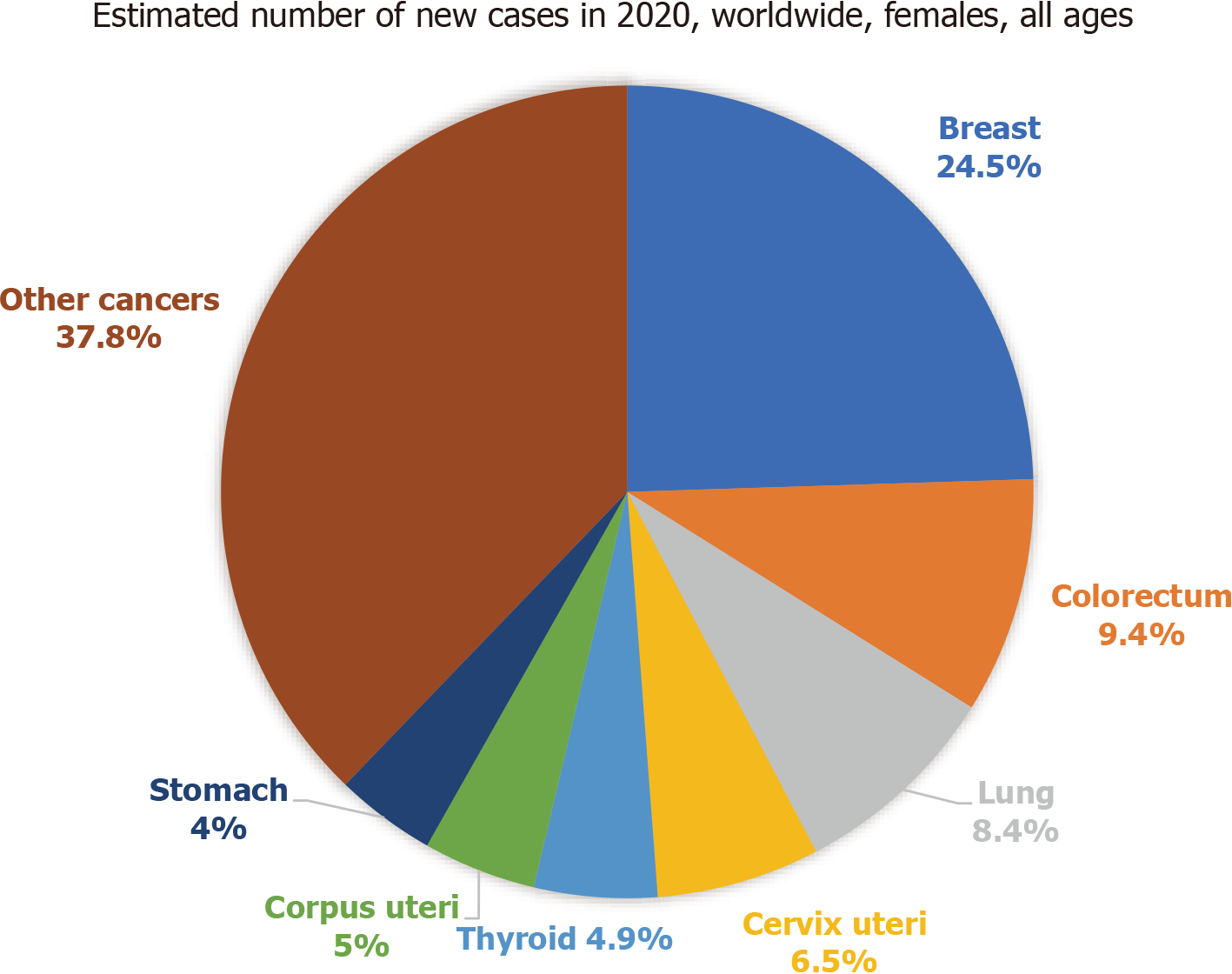

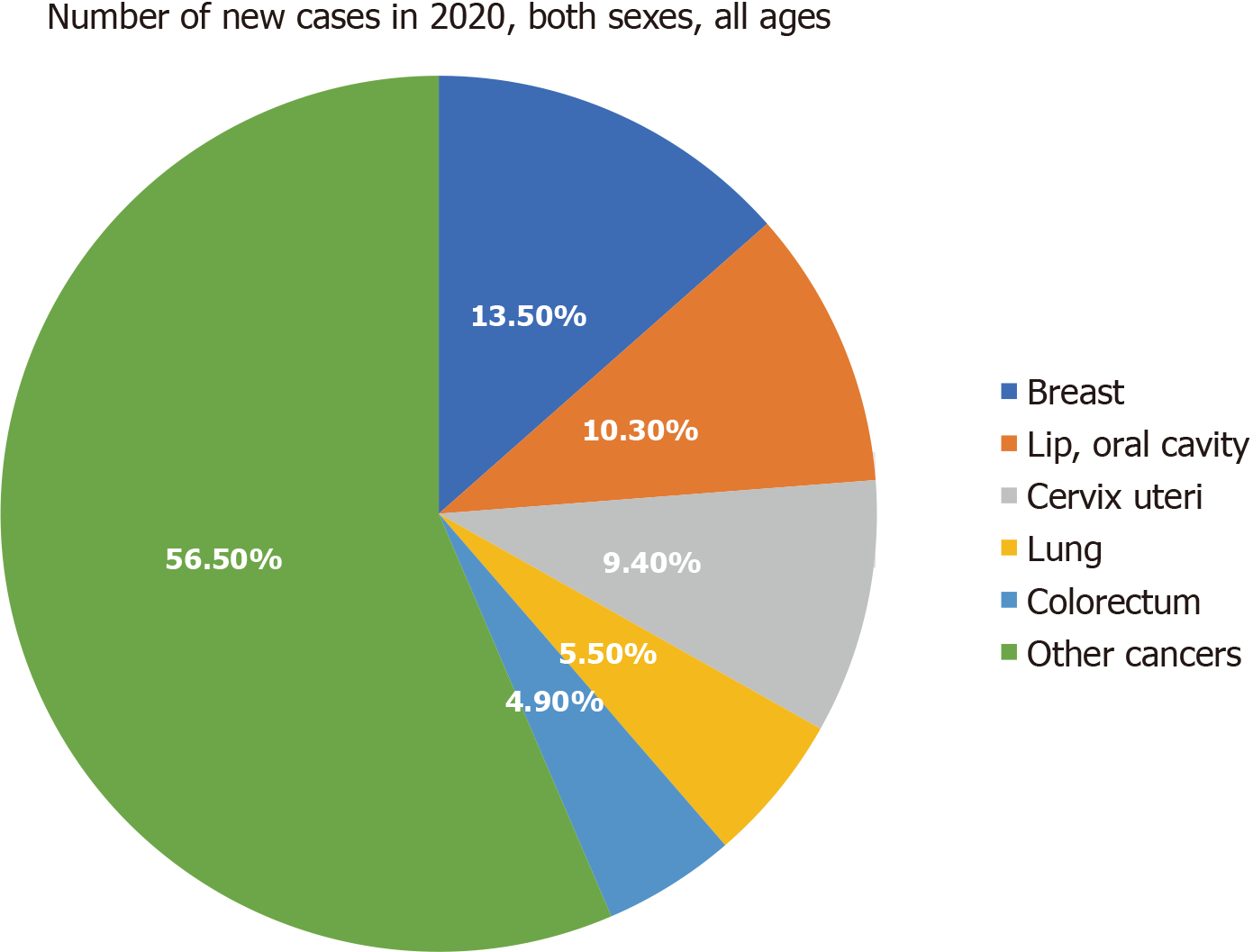

Breast cancer (BC) is the commonest malignancy among women globally. It has now surpassed lung cancer as the leading cause of global cancer incidence in 2020, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases, representing 11.7% of all cancer cases[1]. Epidemiological studies have shown that the global burden of BC is expected to cross almost 2 million by the year 2030[2]. In India, the incidence has increased significantly, almost by 50%, between 1965 and 1985[3]. The estimated number of incident cases in India in 2016 was 118000 (95% uncertainty interval, 107000 to 130000), 98.1% of which were females, and the prevalent cases were 526000 (474000 to 574000). Over the last 26 years, the age-standardised incidence rate of BC in females increased by 39.1% (95% uncertainty interval, 5.1 to 85.5) from 1990 to 2016, with the increase observed in every state of the country[4]. As per the Globocan data 2020, in India, BC accounted for 13.5% (178361) of all cancer cases and 10.6% (90408) of all deaths (Figure 1 and Figure 2) with a cumulative risk of 2.81[5].

Current trends point out that a higher proportion of the disease is occurring at a younger age in Indian women, as compared to the West. The National Cancer Registry Program analysed data from cancer registries for the period from 1988 to 2013 for changes in the incidence of cancer. All population-based cancer registries have shown a significant increase in the trend of BC[6]. In India in 1990, the cervix was the leading site of cancer followed by BC in the registries of Bangalore (23.0% vs 15.9%), Bhopal (23.2% vs 21.4%), Chennai (28.9% vs 17.7%) and Delhi (21.6% vs 20.3%), while in Mumbai, the breast was the leading site of cancer (24.1% vs 16.0%). By the years 2000-2003, the scenario had changed, and breast had overtaken as the leading site of cancer in all the registries except in the rural registry of Barshi (16.9% vs 36.8%). In the case of BC, a significant increasing trend was observed in Bhopal, Chennai and Delhi registries[7].

When it comes to the 5-year overall survival, a study reported it to be 95% for stage I patients, 92% for stage II, 70% for stage III and only 21% for stage IV patients[8]. The survival rate of patients with breast cancer is poor in India as compared to Western countries due to earlier age at onset, late stage of disease at presentation, delayed initiation of definitive management and inadequate/fragmented treatment[9]. According to the World Cancer Report 2020, the most efficient intervention for BC control is early detection and rapid treatment[10]. A 2018 systematic review of 20 studies reported that BC treatment costs increased with a higher stage of cancer at diagnosis. Consequently, earlier diagnosis of BC can lower treatment costs[11].

EARLY DETECTION AND SCREENING PROGRAMMES

Success and failure of screening programs depend on several factors ranging from the presence of proper guidance manuals, development and usage of an appropriate instrument for diagnosis to proper implementation and availability of adequate human resources. Another factor is the efficacy of the screening test in avoiding the risk of false positives and unnecessary biopsies and surgeries[12]. Organised screening programmes provide screening to an identifiable target population and use multidisciplinary delivery teams, coordinated clinical oversight committees and regular review by a multi-speciality evaluation board to maximise the benefit to the target population[13]. Screening strategies are moving towards a risk-based approach rather than a broad age-based and sex-based recommendation. To use this risk-based approach, India needs to assess risk factors and incorporate this information into BC screening[14].

A recent study from Mumbai has reported that clinical breast examination conducted every 2 years by primary health workers significantly downstaged breast cancer at diagnosis and led to a nonsignificant 15% reduction in breast cancer mortality overall (but a significant reduction of nearly 30% in mortality in women aged ≥ 50)[15]. Mammography sensitivity has been reported to vary from 64% to 90% and specificity from 82% to 93%[16]. Indian women have more dense breasts, and there is a lack of adequate mammography machines and trained manpower. This may result in false positives and over-diagnosis. Digital mammography uses computer-aided detection software but remains costly. It is due to these reasons that mass-scale routine mammography screening is not a favoured option for a transitioning country like India.

Ultrasonography has an overall sensitivity of 53% to 67% and specificity of 89% to 99%[17,18] and might be particularly helpful in younger women (aged 40 to 49 years). However, the requirement of trained professionals to perform and interpret ultrasound is a major hurdle. Though breast self-examination is not accepted as an early detection method for BC, this technique, if used diligently and skilfully, can serve as a useful adjunct to making the woman aware of her normal breast[19].

Understanding India-specific differences by utilising genomics may enable the identification of women at high risk of developing cancer, where targeted screening may be cost-effective. There is an urgent need to identify Indian-specific genetic/epigenetic biomarkers. These may have the potential to be used as biomarkers for early detection at the screening stage[20].

TREATMENT OPTIONS IN PAST AND PRESENT

Management of BC is multidisciplinary and has come a long way. In the past, the widely used treatment option was mastectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced BC, triple-negative breast cancer and HER2neu expressing tumours (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). At present, it includes a loco-regional approach (targeting only the tumour with the help of surgery and radiation therapy) and a systemic therapy approach that targets the entire body. The systemic therapy includes endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive disease, chemotherapy, anti-HER2 therapy for HER2 positive disease, bone stabilising agents, polymerase inhibitors for BRCA (breast cancer gene) mutation carriers and, recently, immunotherapy. However, the majority of patients still undergo primary ablative surgical procedures. Gene expression profiling in hormone receptor-positive disease is also a promising option but has financial implications.

From using drugs like cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, etc. in the 1970s for chemotherapy to using their modifications like anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy protocols in the 1980s and 1990s, we have come a long way. Taxanes are the newer additions that show a promising future. The radiation treatment of BC has evolved from 2D to 3D conformal radiotherapy and accelerated partial breast irradiation, aiming to reduce normal tissue toxicity and overall treatment time[21]. The newer additions, viz. intensity-modulated radiation therapy and deep inspiration breath-hold, are still inaccessible to many. The same is the case with brachytherapy.

The outcomes with triple-negative breast cancer are poor, and the treatment options are mainly restricted to systemic chemotherapy. Immunotherapy, poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitors (poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase) and antibody-drug conjugates have the potential to change the current scenario of BC treatment. One important point that should be considered while planning the treatment is that there is a lot of hype regarding the newer drugs that flood the market, however with little or no difference in the survival benefit. Hence it is important to choose wisely.

The field of breast surgery has also evolved from total mastectomy to breast conservation therapy to oncoplastic breast surgery. The rapidly advancing field of oncoplastic breast surgery offers a pragmatic alternative to total mastectomy and breast conservation therapy. It is currently nascent but expected to attain mainstream status in the near future as oncoplastic breast surgery has economic feasibility and cost-effectiveness and is well suited for a low-resource setting such as India[22].

CHALLENGES IN BC CONTROL

Delay in seeking healthcare

Continuously increasing BC prevalence is just the tip of the iceberg. There are many underlying problems that contribute to this mounting burden. In India, nearly 60% of BC cases are diagnosed at stage III or IV of the disease[23]. Most of the patients present to the healthcare facility only when there is a large palpable mass or secondary changes like local skin/chest wall changes are visible. Women tend to ignore the minor symptoms and do not show up at the hospital until it is unbearable, owing to their household responsibilities. Other factors that may contribute to the late presentation include a lack of awareness about the disease, especially in rural areas. This also leads to fewer women performing a self-breast examination, opting for a periodic examination by a healthcare worker or mammography for BC screening, despite it being available for free in a few government hospitals. For those willing to pay for it, mammography is available in private hospitals. This lack of awareness regarding the risk factors and early detection methods of BC is unfortunately even prevalent in 49% of healthcare workers[24].

The initial manifestation of BC, i.e. a lump, is generally not associated with pain, which further adds to the delay in seeking treatment in 50% to 70% of the cases in rural areas[25]. Other factors that may influence the early detection and treatment of BC are the presence of a diagnostic/treatment facility in the nearby area, patient’s preference and trust in the healthcare provider, amount of time required for travelling to the service centre and amount and availability of money that can be spent on the treatment. However, this grim situation has slowly started to change due to various awareness campaigns, and now women have slowly started to understand and value their health. Another deterring factor in seeking early care is the stigma of social embarrassment and isolation. Women not only fear death and contagion by cancer but also fear that their and their family’s reputation would suffer if people knew of their cancer diagnosis, including potential difficulties in their daughter’s wedding. It is also a widespread assumption that cancer, especially in the private parts (breast and genitals) is linked to ”bad” and “immoral behaviour”[26]. The issue of social stigma urgently needs to be addressed through awareness campaigns, as it not only jeopardises early diagnosis but also the treatment-seeking behaviour of women with symptoms of BC.

Delay from the healthcare provider’s side

On average, more than 12 wk of delay is seen in diagnosis and treatment in 23% of patients[27]. A study examined provider’s delay (defined as the period between the first consultation and diagnosis) and observed that the mean provider delay was 80 d in rural areas and 66 d in urban areas[28]. More than half of the women were observed to have a delay of more than 90 d in seeking care. The patient-related delay was observed to be 6.1 wk, and the system-related delay was 24.6 wk with a mean total delay of 29.4 wk in treatment. This led to a poor prognosis[29]. These delays may be attributed partly to the ever-increasing patient load on the health care system and competing priorities.

High attrition rates

After crossing all these hurdles, once the diagnosis is done and treatment is started, there are further hazards. In 1990, India’s facilities for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer were far behind recommendations[30]. Even today, due to a large variation in the health care standards between regions, the quality of treatment for BC patients varies from pathetic to world-class. Few patients are treated at well-equipped centres in a protocol-based manner, while some are subjected to numerous compromises. Fortunately, BC is curable if detected early, but due to various underlying factors, improper treatment provided locally by non-oncologists without standard oncology expertise may lead to the mismanagement of BC cases. At the same time, patients with advanced, metastatic incurable cancer may require only palliative care are referred to tertiary cancer centres. This leads to the improper use of limited, valuable resources.

Another issue that adds to the high attrition rates/loss to follow-up of BC treatment is an unacceptable out-of-pocket expenditure, which is three times higher for private inpatient cancer care in India[30]. More than half the patients from low-income households spend > 20% of their annual household expenditure on BC treatment, leading to catastrophic results[31]. An analysis of three public insurance schemes for anticancer treatment in India published in 2018 revealed inconsistencies in the selection of reimbursed treatments. The reimbursed amount was usually found to be insufficient to cover the total cancer chemotherapy costs, leading to an average budget shortage of up to 43% for BC treatment[32]. Cancer insurance policies can significantly reduce the financial burden caused by out-of-pocket expenditure and prevent catastrophic health expenditure, distress financing and even bankruptcy. However, a study by Singh et al[33] to understand the use of health insurance in India reported a lack of awareness regarding the use of these schemes as the key reason for the low penetration of health insurance policies.

Shortage of resources/skewed distribution of available limited resources

Another problem is a shortage of manpower. India has just over 2000 oncologists for 10 million patients, and the number of oncologists is unevenly spread, being lower in semi-urban and rural areas. Although nearly 70% of the Indian population lives in rural areas, about 95% of facilities for cancer treatment exist in the urban areas of the country. There are also regional variations. About 60% of specialist facilities are in Southern and Western India, whereas more than 50% of the population lives in the Northern, Central and Eastern regions, distorting service provision[34].

There are currently 57 courses for radiotherapy technologists and about 2200 certified radiation technologists in practice in India[35]. As per a recent study, India has just 10% of the total requirement of 5000 radiation therapy units indicating a shortfall of > 4500 machines. The World Health Organization recommends at least one teletherapy unit per million population, and there is a shortfall of 700 teletherapy units[35]. If we look at the treatment infrastructure, at least half of patients with cancer will be judged to need radiotherapy at some point. Yet only 26% of the population, living in the Eastern region of India, have immediate access to only 11% of radiotherapy facilities[36]. Nearly 40% of hospitals in India are not adequately equipped with advanced cancer care equipment. Very few centres in the country provide integrated surgical and chemoradiation for BC. Nearly 75% of the patients in the public sector do not have access to timely radiotherapy[37].

All of these factors aid in raising the overall cost of BC treatment for the common person. They are forced to make out-of-pocket cancer care payments, as most of the patients have to bear the cost of therapy. The government facilities are inadequate in number to cater to a large number of patients. Thus, patients are required to go for treatment in major cities along with their attendants, resulting in loss of livelihood of both the patient and her attendants. There is an urgent need to establish a larger number of cancer care facilities accessible to those living in rural areas so that the gap of cancer detection and treatment services may be bridged.

RAYS OF HOPE/WAY FORWARD

The integrative approach

The rising human cost, both social and economic, of BC underscores the need for more holistic, multidimensional approaches that encompass the cancer care continuum including prevention, early detection, treatment, palliation and survivorship. A balanced approach is necessary to integrate traditional medical practices into mainstream oncology practice, starting with a meaningful discussion among all the relevant stakeholders and identifying the areas where the benefits of a complementary approach are beyond doubt[38]. Exercise has been proven to be an effective, safe and feasible tool in combating the adverse effects of treatment, prevents complications and decreases the risk of BC-specific mortality[39]. A recent review has reported evidence that diet-related and physical activity-related interventions for the primary prevention of BC are cost-effective[40]. Such lifestyle modifications need to be included in mainstream treatment planning.

The internet era

Screening programmes in high-income countries that have increased patient participation have done so with high-quality and periodic education programmes with campaigns tailored to the specific cultural context of a community[41]. This can only be achieved by creating and sustaining the level of awareness among the general population. One effective way of doing that is providing information on BC to the relatives/patients in the hospital setting. However, due to the ever-increasing patient burden, it is not always possible for healthcare providers to give appropriate time and counselling to the people. The distribution of pamphlets with valuable information may be the cause. In recent times, the Internet is being increasingly used as a reliable source to seek health-related information[42,43]. A lot of people search for information online. Having a credible source of information that can be revisited as and when required by the people is always a plus. Keeping these things in mind a website ‘Cancer India’ was developed by the National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research providing comprehensive information on common cancers in India, including BC, in layman’s language (available in English and Hindi). A recent evaluation by this group reported that the website managed to serve the intended purpose of improving cancer awareness with reasonable success[44].

Involvement of community health workers

Community participation with the engagement of the health system and local self-government are required for implementing a comprehensive cancer screening strategy. A BC screening program using local volunteers for early detection is feasible in low-income settings, thereby improving survival[45]. Community health workers can play an important role in the early detection of BC in low- and middle-income countries, with responsibilities including awareness-raising, conducting clinical breast examinations, making referrals and supporting subsequent patient navigation. However, this promise can only be turned into genuine progress if these activities are appropriately supported and sustained. This will involve adopting contextually appropriate early detection initiatives that are embedded within the broader health system where community health workers are appropriately trained, equipped, paid and supported with appropriate links to specialist oncology services. A recent study reported the effectiveness of the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes model training program in reaching primary care physicians across the country and improving their knowledge and skills related to screening for breast, oral and cervical cancer[46].

Early diagnosis

With advancements in molecular diagnostics and therapeutics, newer non-invasive prognostic biomarker tests to detect BC at a very early stage, such as digital breast tomosynthesis and breast biopsy techniques, are becoming available[47]. Above all, early detection programmes in low- and middle-income countries must make provisions for every individual at risk of BC. This will mean considering the needs of the hardest individual to reach first, so that no woman is left behind in the goal to end unjust and untimely deaths attributable to the leading cause of female mortality in low- and middle-income countries[48].

Out of pocket expenditure

To address the issue of out-of-pocket expenditure and to reach out to the poorer section of the society, a scheme called Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana under the new universal healthcare programme named “Ayushman Bharat” has been recently launched in India. It is the largest health assurance scheme in the world that aims at providing a health cover of Rs. 5 Lakhs (6814 USD) per family per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation to over 10.74 crores (approximately 107 million) poor and vulnerable families (approximately 500 million beneficiaries) that form the bottom 40% of the Indian population[49]. The Indian government’s efforts to bring anti–HER2 drug under-pricing regulations have enhanced access and improved outcomes. The launch of low-cost T-DM1 (the antibody-drug conjugate trastuzumab emtansine) and anti–HER2 therapy biosimilars is keenly awaited. Linking cancer registry data with Ayushman Bharat, mortality databases and the Hospital Information System could improve cancer registration, follow-up and outcome data[50].

Newer initiatives

There are several health-tech start-ups that aid in different stages of cancer care. For example, Niramai® uses machine learning and big data analytics to develop low-cost diagnostics for BC[51]. Oncostem® uses multi-marker prognostics tests that aid in personalised treatment[52], and UE Lifesciences® uses contactless and radiation-free handheld screening devices[53] that may come in handy during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) times. Panacea® and Mitra Biotech®[54] are start-up companies that deal with providing precision therapies. Tumourboard® and Navya Network®[55] provides affordable and precise consultations. There are several drug-patient assistance programs from pharmaceutical companies like Roche®, Novartis®, Dr Reddys®, etc. that help in following patient-centric care from beginning to end. The BC Initiative 2.5 is a global campaign to reduce disparities in BC outcomes and improve access to breast health care worldwide. It is a self-assessment toolkit that can help countries conduct a comprehensive breast health care situational analysis[56] Apart from these, patient navigation strategies are also rapidly growing and evolving concepts. ‘Kevat’ is the first initiative in India to create a trained task force to facilitate the cancer patient’s journey from entry to the hospital to follow-up. It is a nascent area of speciality in cancer care that is set to target the pressing need of well-trained patient navigators in onco-care[57].

Apart from these, the World Health Organization, on March 9, 2021, introduced a Global Breast Cancer Initiative to reduce global breast mortality by 2.5% by 2040. The aim is to reduce 2.5 million global deaths, particularly in low-income countries, where the progress to tackle the disease has been relatively slow. An evidence-based technical package will be provided to countries as part of the initiative[58]. Such initiatives instil faith in the future for better breast cancer management.

COVID-19 challenge

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged the prioritisation of various diseases in healthcare systems across the globe, and BC patients are no exception. It impacted their access to physicians, medication and surgeries. Nearly 70% of patients could not access life-saving surgeries and treatment. Chemotherapy treatments and follow-ups were postponed due to lockdowns[59,60]. A recent study reported that the average monthly expenditure of cancer patients had increased by 32% during the COVID-19 period while the mean monthly household income was reduced by a quarter. More than two-thirds of the patients had no income during the lockdown, and more than half of the patients met their expenditure by borrowing money. The incremental expenditure coupled with reduced or no income due to the closure of economic activities in the country imposed severe financial stress on patients with BC[61].

It became of utmost importance to balance between the benefits and risks associated with BC treatment[62]. There are different treatment modalities and each case is different. The shorter duration of radiotherapy, transient spacing of chemotherapy in metastatic BC setting, if deemed feasible, oral hormone therapy to delay surgery and judicious use of immunomodulators are some recent guidelines in evidence-based practice in this unprecedented crisis[63]. The core idea is to delay the surgery until the pandemic is over whenever feasible. Additionally, apart from healthcare management, one area that has suffered tremendously due to the infectious outbreak is cancer research[64]. The estimated decrease in cancer funding in India ranges from 5% to 100%, as many funding agencies have cancelled calls for funding. The private/charity sector is the worst hit, with an estimated decrease of more than 60% of its funding[65]. A robust health system is a prerequisite for providing the facilities for the treatment of BC that is diagnosed through the early detection programmes, whether through screening or the presence of symptoms[66]. Of course, it goes without saying that a proper evaluation of the programmes will not only allow improvement of quality of services but also generate valuable evidence on the effectiveness of screening and early diagnosis in the countries ”in transition”[67].

CONCLUSION

To conclude, the BC burden is rising at a rate much faster than it was a decade ago. Acknowledging that BC is one of the foremost cancers in India now would be the first step towards making people cognizant of the disease. It is fast developing into a public health crisis, and society’s discomfort to talk about women’s bodies has made the situation even worse. To combat the consequences as a country, better preparedness is essential. A robust awareness campaign and effective implementation of a national cancer screening program are the need of the hour. We also need to stand up and deliver on the healthcare front. The shortage of skilled manpower and infrastructural requirements need to be met, and for this, the total healthcare budget of the country needs to be increased. In the jargon of the challenges of BC control, prioritising the adoption of a preventive approach and early detection would go a long way. Another important aspect is the country’s preparedness for unprecedented events like COVID-19, for which there should be a separate provision to deal with public health disasters. Creating a cadre of trained medical and paramedical professionals, efficient utilisation and timely upgrading of skills of the existing healthcare workforce along with adopting newer technologies would further the cause of BC control.