Published online Nov 24, 2021. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v12.i11.1083

Peer-review started: May 22, 2021

First decision: August 18, 2021

Revised: August 20, 2021

Accepted: September 30, 2021

Article in press: September 30, 2021

Published online: November 24, 2021

Processing time: 180 Days and 24 Hours

Foreign body granuloma (FBG) is a well-known type of granulomatous formation, and intraabdominal FBG (IFBG) is primarily caused by surgical residues. Multifocal IFBGs caused by gastrointestinal perforation is an extremely rare and interesting clinicopathological condition that resembles peritoneal dissemination. Here, we present a case of IFBGs mimicking peritoneal dissemination caused by bowel perforation and describe the value of intraoperative pathological examinations for rapid IFBG diagnosis.

An 86-year-old woman with an incarcerated femoral hernia was admitted to the hospital and underwent operation. During the operation, the incarcerated ileum was perforated during repair due to hemorrhage necrosis, and a small volume of enteric fluid leaked from the perforation. The incarcerated ileum was resected, and the femoral hernia was repaired without mesh. Four months later, a second operation was performed for an umbilical incisional hernia. During the second operation, multiple small, white nodules were observed throughout the abdominal cavity, resembling peritoneal dissemination. The results of peritoneal washing cytology in Douglas’ pouch and the examination of frozen nodule sections were compatible with IFBG diagnosis, and incisional hernia repair was performed.

IFBGs can mimic malignancy. Intraoperative pathological examinations and operation history are valuable for the rapid diagnosis to avoid excessive treatments.

Core Tip: Multifocal intraabdominal foreign body granulomas (IFBGs) caused by gastrointestinal perforation are clinically rare and mimic peritoneal dissemination. An 86-year-old woman underwent an operation to treat an incarcerated femoral hernia; however, the incarcerated ileum was perforated due to hemorrhage necrosis, resulting in incarcerated ileum resection. After 4 mo, a second laparoscopic operation was conducted for an umbilical incisional hernia; however, small, white nodules were identified throughout the entire abdominal cavity, mimicking peritoneal dissemination. Using intraoperative cytology and frozen sections, the nodules were diagnosed as IFBGs. IFBGs sometimes mimic peritoneal dissemination, and intraoperative pathological examinations are effective for rapid diagnosis.

- Citation: Ogino S, Matsumoto T, Kamada Y, Koizumi N, Fujiki H, Nakamura K, Yamano T, Sakakura C. Foreign body granulomas mimic peritoneal dissemination caused by incarcerated femoral hernia perforation: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2021; 12(11): 1083-1088

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v12/i11/1083.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v12.i11.1083

A foreign body granuloma (FBG) is a tissue reaction caused by retained foreign bodies, and intraabdominal FBGs (IFBGs) are typically caused by materials used in a previous operation, such as surgical sutures, gauze, and sponges[1-3]. However, in rare cases, bowel perforation, bile or gallstone spillage, and foreign bodies unrelated to operations, such as fish bones, can result in IFBGs[4-6]. Furthermore, IFBGs sometimes occur multifocally and can closely resemble peritoneal dissemination, leading to misdiagnosis[5,7]. Here, we present a case of IFBGs mimicking peritoneal dissemination 4 mo after an operation to treat an incarcerated and perforated femoral hernia.

An 86-year-old woman presented to our hospital with anorexia and vomiting for 3 d.

Her medical history was unremarkable.

Past appendectomy.

No special in personal and family history.

Severe pain with redness and a palpable bulge was observed in the right inguinal area.

The laboratory workup showed a white blood cell count of 17.1 × 109/L and C-reactive protein levels at 6.13 mg/dL.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a right incarcerated femoral hernia with small bowel obstruction.

FBG (see TREATMENT section).

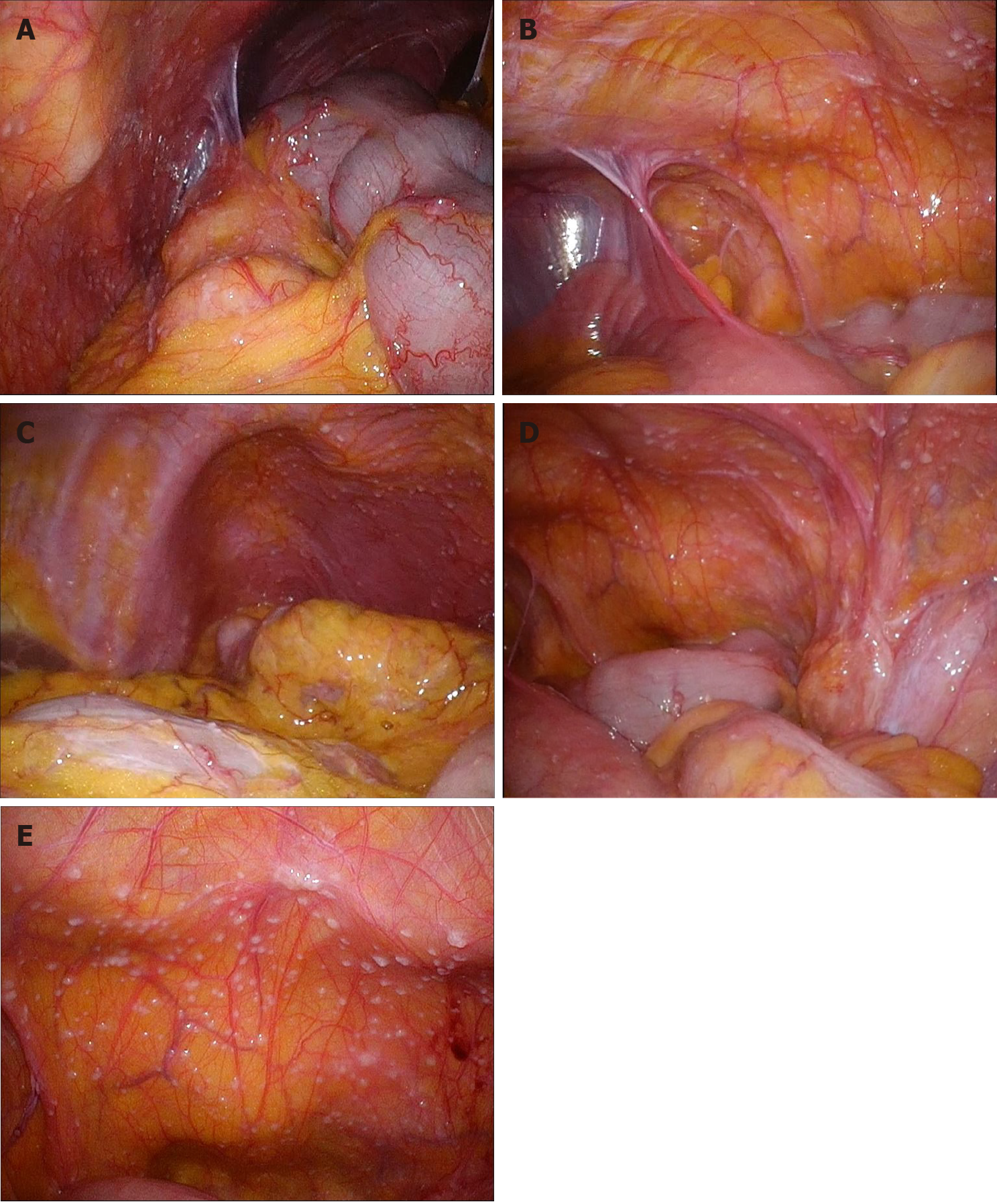

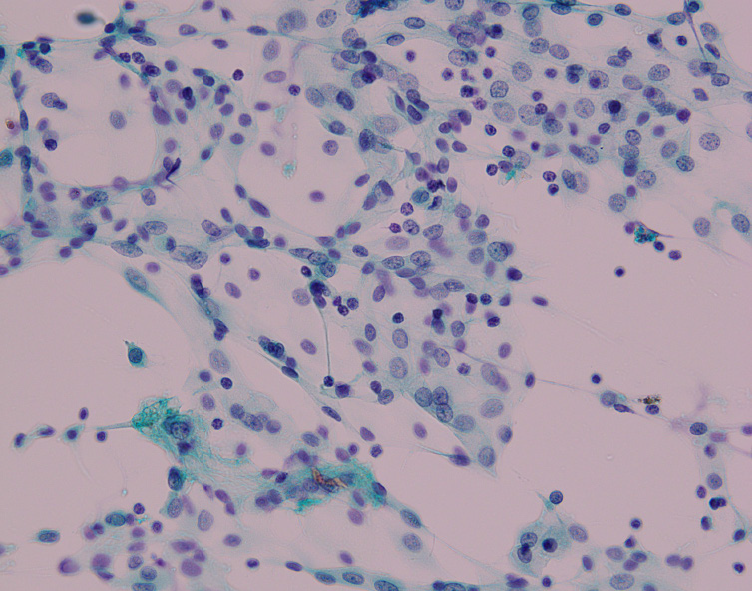

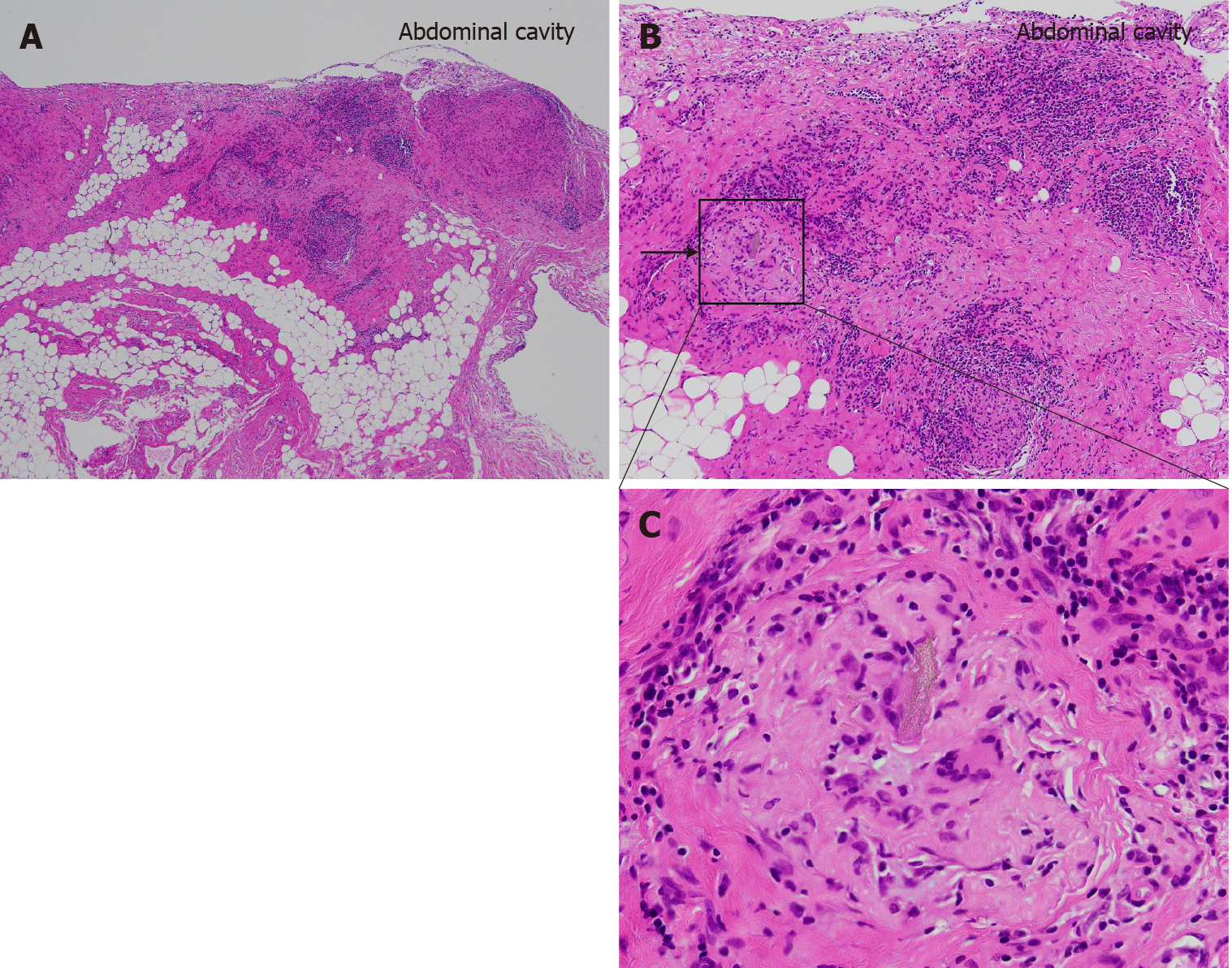

The laparoscopic repair of an incarcerated femoral hernia was attempted; however, the incarcerated ileum was perforated during the repair because it had become necrotic. The necrotic ileum was resected, and the right femoral hernia was repaired using the McVay procedure (Figure 1). Although postoperative intensive care for septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation was necessary, the patient was discharged one month after the operation. The patient revisited our hospital 3 mo later due to an umbilical incisional hernia, and laparoscopic incisional hernia repair was performed. During the operation, the hernia orifice, 11 cm in diameter, was identified at the umbilical wound, and multiple small white nodules expanded throughout the entire abdominal cavity (Figure 2). We suspected the peritoneal dissemination of some tumors. Because no observable tumor could be located in the abdominal cavity, peritoneal wash cytology of Douglas’s pouch was performed, and frozen sections of the nodules were examined. The cytology was negative for malignancy (Figure 3), and the frozen sections showed a multinucleated giant cell containing a foreign body, surrounded by inflammatory cells, fibrosis, and granulomatous formations (Figure 4), which was compatible with an FBG reaction. Therefore, laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair with hernia orifice closure (IPOM-plus) was performed.

The postoperative clinical course was uneventful, and no malignant findings were observed on chest-to-abdominal enhanced CT or gastrointestinal and colon endoscopy. No malignancy was detected, and no recurrence of hernia was observed during 7 mo of follow-up.

FBG is a chronic immune reaction induced by the presence of a foreign body. IFBG is typically caused by retained surgical residues, bowel perforation, bile spillage, gallstones, or fish bones[1,2,4-6,8]. Suture granulomas are the most common type associated with surgical residuals, although gauze and sponges have also been reported[1-3]. IFBGs occasionally resemble tumorous nodules and sometimes occur multifocally, which can mimic peritoneal dissemination[2,8]. IFBG is also well-known to be caused by glove powder used in operations. IFBGs associated with lycopodium, talcum, and starch powders from surgical gloves have previously been reported, and these IFBGs can be quite difficult to differentiate from cancerous nodules[7,9,10]. Akita et al[5] reported that food starch released from gastrointestinal perforations could cause multiple IFBGs, mimicking peritoneal dissemination; they reported a case in which tenderness and guarding over the entire abdomen was observed due to a gastric cancer perforation, which was treated surgically. Two months later, many small, white granulomas mimicking peritoneal dissemination were observed, particularly in the upper abdominal cavity, which were diagnosed as IFBGs based on frozen sections during the second operation. In the pathological findings, saburra was observed at the center of the granuloma.

In the present case, multiple small, white nodules that expanded throughout the entire abdominal cavity were observed during the second operation, which were extremely difficult to differentiate from peritoneal dissemination. A multinucleated giant cell containing a foreign body similar to saburra and surrounded by inflammatory cells and granuloma formation was observed pathologically; thus, these nodules were diagnosed as IFBGs and were thought to be caused by food starch, similar to the previously reported case[5], particularly as no evidence of malignancy was identified either during or after the operations.

FBG is one type of non-infectious granulomatous reaction, characterized by the presence of a foreign body surrounded by granuloma formations in foreign body giant cells. FBGs have also been associated with granuloma formation due to an excessive immune response to foreign bodies, potentially related to allergic reactions and microbiological factors[11]. Intriguingly, in the present case, the IFBG expanded to the entire abdominal cavity at the time of the second operation, although the amount of enteric fluid that leaked from the perforation was limited to a small range and was localized within the lower abdominal cavity during the first operation. Because the lower abdominal cavity was rinsed after the resection of the incarcerated ileum during the first operation, the remaining food particles released from the small enteric fluid leak should have been minimized and at low concentrations, which suggested that each IFBG was either caused by an extremely minute food starch quantity or represented an allergic response, resulting in the accumulation of microbiological factors. Furthermore, the characteristic histological findings of FBG were very supportive of an IFBG diagnosis, especially during the operation. The misdiagnosis of IFBGs as malignancies can potentially lead to ineffective or unnecessary treatments. A previous case reported IFBGs mimicking peritoneal dissemination 3 mo after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, resulting in the wedge resection of the liver and transverse colon and omentectomy, and IFBGs were later diagnosed pathologically as likely due to bile or gallstone spillage[6]. As reported by Akita et al[5], intraoperative cytology and frozen sections are valuable for the rapid diagnosis of IFBGs. In the current case, these quick pathological examinations performed during the operation provided an important and powerful method for differentiating IFBGs from peritoneal dissemination.

The physiologic activation of histiocytes generally occurs within 24-48 h[12]; however, the time required for granulomatous formation resembling nodules remains unclear. In the current case, 4 mo was sufficient for the observed granulomatous formation. The percentage of granulomas observed during operations decreases gradually, from 37% if the previous operation was performed within 6 mo to 18% when the previous operation occurred more than 2 years prior[1]. Granulomas that resemble peritoneal dissemination can form within 2 mo, according to Akita et al[5], and this occurred within 4 mo in the current patient. Therefore, the interval between first and second operations also supports the diagnosis of IFBG.

In conclusion, multiple IFBGs caused by bowel perforations are associated with a very rare clinicopathological condition and can mimic peritoneal dissemination. A history of past operations and the interval between the current and past operations can be helpful for distinguishing between IFBGs and peritoneal dissemination, and intraoperative cytology and frozen sections are extremely valuable methods for the rapid diagnosis of IFBG, which can prevent misdiagnosis and avoid the use of ineffective or excessive treatments.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu YC S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Luijendijk RW, de Lange DC, Wauters CC, Hop WC, Duron JJ, Pailler JL, Camprodon BR, Holmdahl L, van Geldorp HJ, Jeekel J. Foreign material in postoperative adhesions. Ann Surg. 1996;223:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wang H, Chen P. Surgicel® (oxidized regenerated cellulose) granuloma mimicking local recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1497-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ezaki T, Okamura T, Yoshida Y, Kodate M, Shirakusa T, Tanimoto A, Hiratsuka R. Foreign-body granuloma mimicking an extrahepatically growing liver tumor: report of a case. Surg Today. 1994;24:829-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamamoto T, Hirohashi K, Iwasaki H, Kubo S, Tanaka Y, Yamasaki K, Koh M, Uenishi T, Ogawa M, Sakabe K, Tanaka S, Shuto T, Tanaka H. Pseudotumor of the omentum with a fishbone nucleus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:597-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Akita H, Watanabe Y, Ishida H, Nakaguchi K, Okino T, Kabuto T. A foreign body granuloma after gastric perforation mimicking peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39:795-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jeong H, Lee HW, Jung HR, Hwang I, Kwon SY, Kang YN, Kim SP, Choe M. Bile Granuloma Mimicking Peritoneal Seeding: A Case Report. J Pathol Transl Med. 2018;52:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Giercksky KE, Qvist H, Giercksky TC, Warloe T, Nesland JM. Multiple glove powder granulomas masquerading as peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:299-304. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Shan GD, Chen ZP, Xu YS, Liu XQ, Gao Y, Hu FL, Fang Y, Xu CF, Xu GQ. Gastric foreign body granuloma caused by an embedded fishbone: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3388-3390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | LEE CM Jr, LEHMAN EP. Experiments with nonirritating glove powder. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947;84:689-695. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ellis H. The hazards of surgical glove dusting powders. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;171:521-527. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Schmitt A, Volz A. Non-infectious granulomatous dermatoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:518-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017;7:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |