Published online Apr 24, 2020. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i4.243

Peer-review started: December 8, 2019

First decision: January 5, 2020

Revised: March 6, 2020

Accepted: March 12, 2020

Article in press: March 12, 2020

Published online: April 24, 2020

Processing time: 136 Days and 9 Hours

Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra is a rare type of aggressive cancer with a poor prognosis. Clear cell carcinoma of the urethra represents less than 0.02% of all malignancies in women. Adenocarcinomas account for 10% of female urethral carcinomas, of which 40% are the clear cell variant. Determining the presence or absence of certain mutations through genetic testing may predict whether a patient with cancer may benefit from a particular chemotherapy regimen.

A 40-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of slow urinary flow and a 3-mo history of urinary urgency and frequency as well as gross hematuria. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scan demonstrated enlarged lymph nodes in the abdomen and pelvis. A biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node microscopically confirmed a metastatic adenocarcinoma of the urethra. Specialized genetic testing determined personalized chemotherapy. She was treated successfully with a non-platinum-based chemotherapy consisting of paclitaxel and bevacizumab. Following 3 cycles of paclitaxel and bevacizumab, she attained significant clinical improvement, and response by FDG-Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging showed a definite improvement in size and metabolic activity. She achieved complete response after 6 cycles of therapy by PET scan. The patient concluded 11 cycles of paclitaxel and bevacizumab, and a subsequent PET scan confirmed progression of metastatic disease. The patient was then treated with two cycles of doxorubicin after which a PET scan revealed a mixed response to the treatment.

We report the first case of a patient with metastatic clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra who underwent personalized chemotherapy after testing for cancer gene alterations. Our unique case represents the safe and effective use of non-platinum-based chemotherapy in clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra.

Core tip: Specialized genetic testing determines the presence or absence of certain mutations which may predict whether a patient with cancer may benefit from a specific chemotherapy regimen. We report the first case of a patient with metastatic clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra who underwent personalized chemotherapy after testing for cancer gene alterations. The patient achieved complete response after 6 cycles of paclitaxel and bevacizumab by positron emission tomography scan. Our case highlights the safe and effective use of non-platinum-based chemotherapy in clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra.

- Citation: Shields LBE, Kalebasty AR. Personalized chemotherapy in clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2020; 11(4): 243-249

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i4/243.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i4.243

Clear cell carcinoma of the urethra represents less than 0.02% of all malignancies in women with an annual age-adjusted incidence rate of 1.5 per million females in the United States[1]. Adenocarcinomas account for 10% of female urethral carcinomas, of which 40% are the clear cell variant[2-4]. The majority of cases occur in postmenopausal women, with a mean age of 58 years[5]. Presenting symptoms often include dyspareunia, dysuria, hematuria, pelvic pain, and urinary obstruction, urgency, frequency, and incontinence[1,6-8].

Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra is thought to arise from surface urothelial metaplasia, mesonephric (Wolffian), or Müllerian rests[4,5,7]. It is often located proximally in the urethra with a tendency to metastasize and is associated with urethral diverticulum[3-9]. The most significant prognostic factors include pathological stage and tumor location, with proximal tumors having a worse prognosis[4,10]. A diagnostic urethrocystoscopy and biopsy are usually performed to confirm the diagnosis of clear cell carcinoma of the urethra which are frequently followed by more extensive surgical intervention[5,7]. Pelvic radiation is occasionally considered when there is lymph node involvement, whereas chemotherapy has shown to be of minimal benefit[5]. Genetic testing for personalized and targeted cancer therapy detects mutations in the DNA of cancer cells[11]. Determining the presence or absence of certain mutations may predict whether a patient with cancer may benefit from a particular chemotherapy regimen.

We report the successful use of non-platinum-based chemotherapy in clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra. The distinctive characteristics, differential diagnosis, and management of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra are discussed.

A 40-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of slow urinary flow and a 3-mo history of urinary urgency and frequency as well as gross hematuria.

She denied fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and flank pain.

The patient had a 3-year history of slow urinary flow and a 3-mo history of urinary urgency and frequency as well as gross hematuria.

Past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, shingles, and hypothyroidism.

Height: 5’ 5.5” (1.66 m); Weight: 287 lbs (130.2 kg); Body Mass Index: 47.03 kg/m2. Physical examination detected one cyst-like lesion measuring approximately 1.0 cm in the distal urethra.

An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scan with IV contrast demonstrated multiple bladder calculi, enlarged lymph nodes in the abdomen and pelvis with the largest in the right inguinal area measuring 2.2 cm, and a rounded mass measuring 4.0 cm arising from the left adrenal. Cystoscopy revealed multiple bladder calculi and inflammatory tissue throughout the course of the urethra. The former, with a total stone volume less than 2.5 cm, were extracted. The actively bleeding tissue emanating from the urethral meatus was excised. The diagnosis of the tumor arising from the urethra was based on cystoscopic findings revealing that the tumor was in the urethra and not in the bladder and bladder neck.

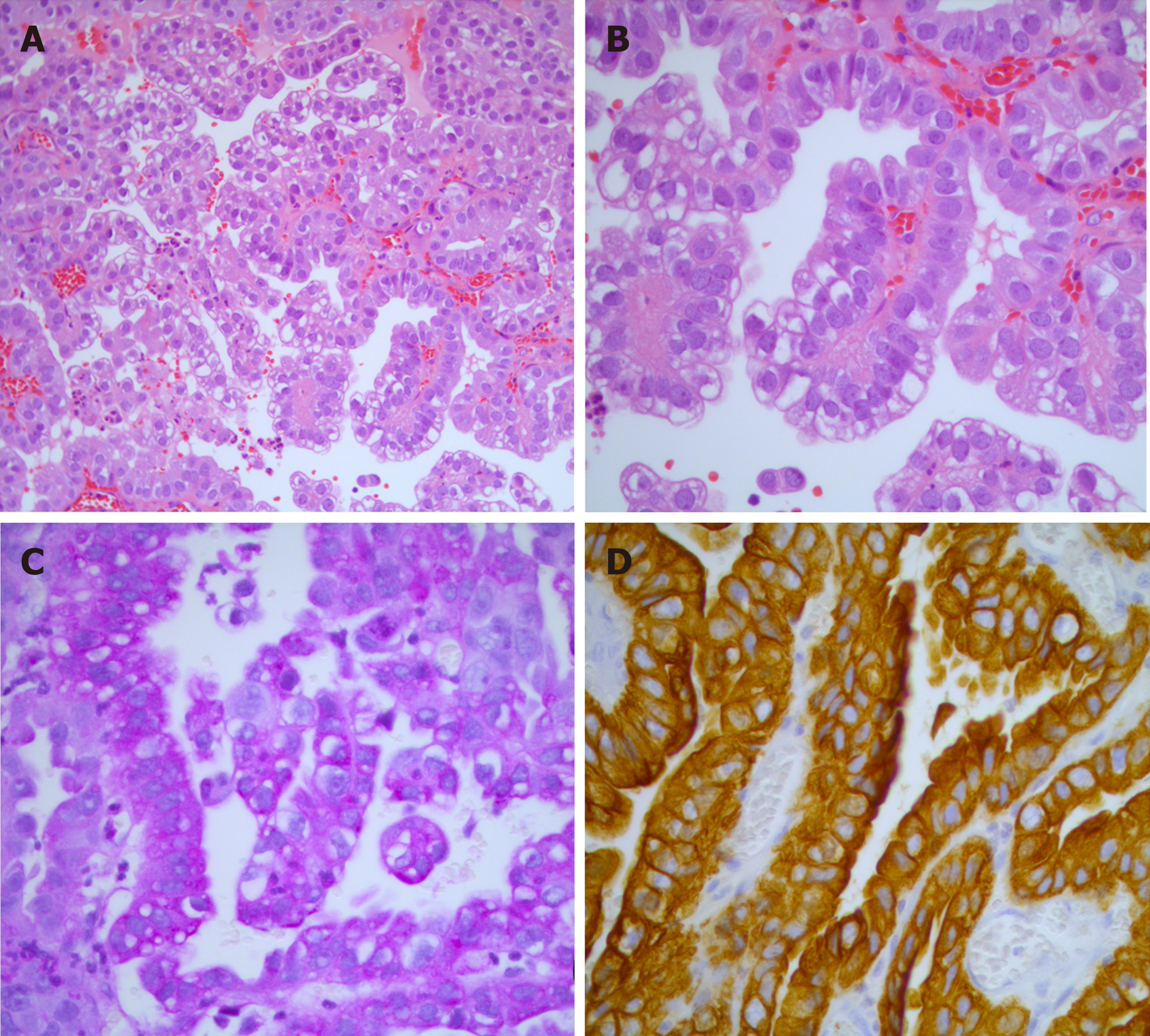

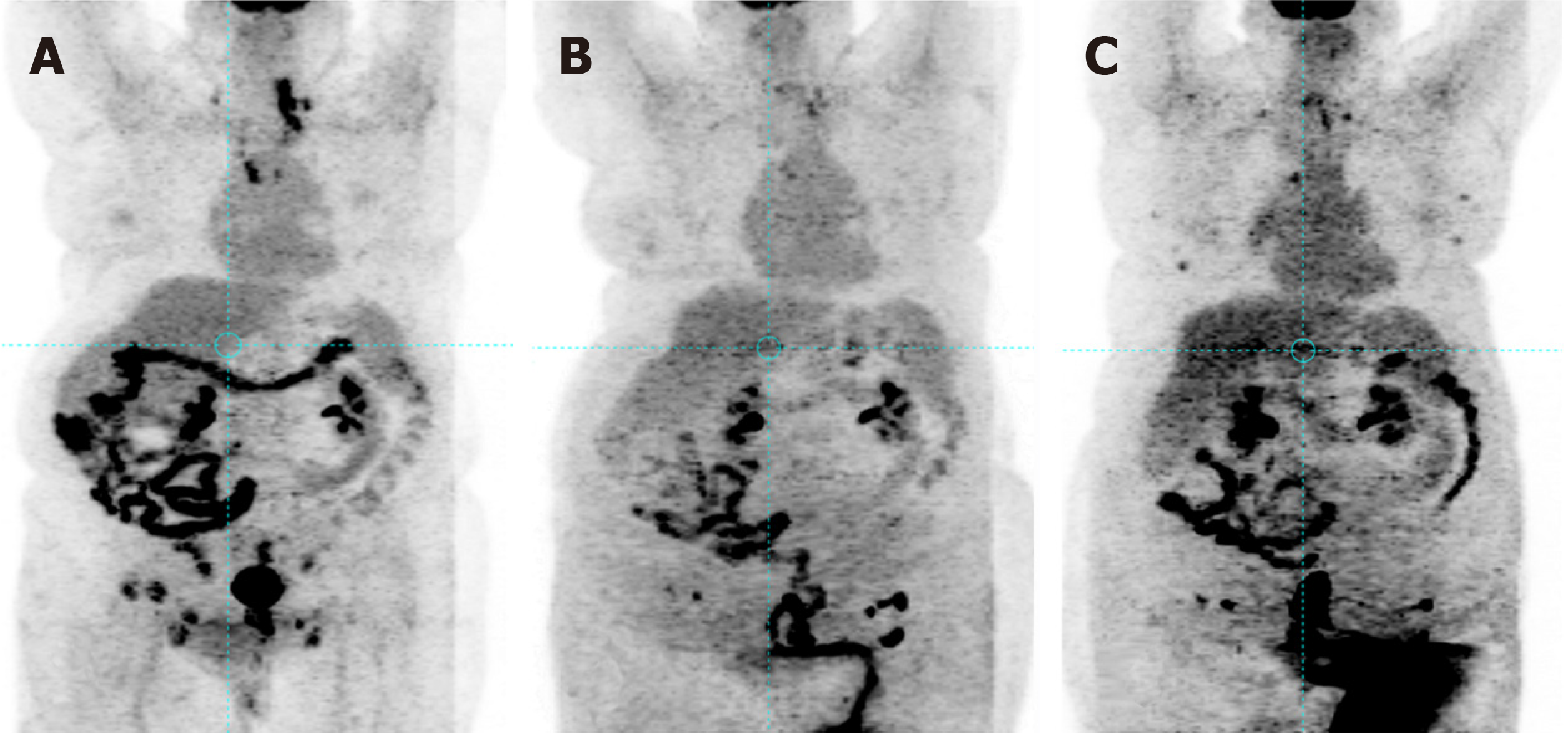

Histological analysis demonstrated a proliferation of cuboidal cells lining tubulopapillary structures that merged with the squamous mucosa of the urethra (Figure 1A and B). While some cells were relatively uniform with round nuclei and others exhibited nuclear pleomorphism, rare cells showed marked nuclear enlargement. The cytoplasm varied from eosinophilic to vacuolated to focally clear (Figure 1A and B). Immunohistochemical and histochemical stains were positive for periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 1C), cytokeratin (CK) AE1/AE3, CK7 (Figure 1D), PAX8, and CD15 and negative for mucicarmine, CK20, p63, and CK 5/6. The Ki-67 proliferative index was 25%-30% overall but as high as 50%-60% in some areas. The patient was diagnosed with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed multiple enlarged hypermetabolic lymph nodes throughout her body, a 4.0 cm × 3.7 cm hot soft tissue density mass near the proximal urethra, and a 4.3 cm soft tissue left adrenal mass (Figure 2A). An ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node was performed.

A metastatic poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma revealing stage IV disease was microscopically confirmed.

The patient underwent suprapubic catheter placement with ongoing dysuria and hematuria. She was seen in medical oncology consultation, and limitations for offering systemic treatments were discussed. A tumor sample was submitted for specialized testing (BiospecifxR, Precision Therapeutics, Inc., Eagen, MN, United States) to determine personalized chemotherapy. The process to determine the individualized chemotherapy took one month to complete. The findings revealed a positive angiogenesis pathway for the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor[12,13], ERCC1[14-16], BRCA1[16-19], and Topo2α[20-22]. ERCCA positivity excluded platinum-based therapy, while BRCA1 positivity was the rationale for taxane-based therapy. Vascular endothelial growth factor positivity indicated the use of bevacizumab.

After 3 cycles of paclitaxel and bevacizumab, a PET scan showed a definite improvement in size and metabolic activity in mediastinal, right iliac, obturator, and bilateral inguinal adenopathy (Figure 2B). The patient achieved radiographic complete response on restaging PET scan after 6 cycles of therapy (Figure 2C). Bilateral lower extremity edema was the only complication which delayed one cycle of combination therapy. The patient concluded a total of 11 cycles of paclitaxel and bevacizumab, reflecting a progression-free survival of 12 mo. A PET scan subsequently confirmed multiple areas of metastatic disease, including the mediastinum, arch of C1, liver, and spleen.

The patient was treated with two cycles of doxorubicin as the specialized testing revealed Topo2α positivity. A PET scan subsequently demonstrated a mixed response to the doxorubicin with some lymph nodes appearing less glucose avid and others having increased metabolic activity as well as a moderate amount of ascites in the abdomen and pelvis, most likely due to peritoneal carcinomatosis. The patient underwent a paracentesis, with aspiration of 4500 mL of fluid.

The patient developed complications from pseudomonas urinary tract infection likely from a suprapubic tube and was hospitalized. She died two weeks later, indicating a 14-mo overall survival.

A comprehensive examination of the differential diagnosis is imperative to accurately diagnosis and treat clear cell carcinoma of the urethra. The histology of clear cell carcinoma of the urethra is marked by tubule-cystic, papillary, and solid patterns, while the cytology often displays clear cytoplasm, hobnail cells, flat to cuboidal morphology, nuclear pleomorphism, tumor necrosis, and mitotic activity[1,5-9]. In addition, the immunohistochemical staining is often positive for PAX1, PAX8, CK 7, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, and p53 with an elevated Ki-67 (greater than 25%)[1,4,5]. Nephrogenic adenoma closely mimics clear cell carcinoma of the urethra with the triad of tubulocystic, papillary, and solid growth pattern although does not possess mitotic activity and there is no infiltrative or prominent solid growth pattern[1,5,9]. Additionally, nephrogenic adenoma does not have an increased Ki-67 proliferative index, a positive p53, and does not give rise to clear cell carcinoma of the urethra. Metastatic clear cell carcinoma of the female genital tract and metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma should also be excluded[4,6,8].

Appropriate imaging used in the diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra includes ultrasound, computed tomography scan, isotope bone scan, and magnetic resonance imaging, with the latter demonstrating preservation of the intratumor urethra, a small tumor height-to-width ratio, as well as a urethral diverticulum and intratumoral septa[3,5]. In our case, FDG-PET results correlated with clinical and tumor response by evaluating the size and activity of metastatic sites. Following diagnostic urethrocystoscopy and biopsy with confirmation of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra, a dilemma exists regarding the extent of surgical resection. In 2013, the European Association of Urology assigned a grade B recommendation for primary urethral carcinoma to use urethra-sparing surgery for anterior urethral cancers, if negative surgical margins could be achieved[23]. However, a more radical surgery such as anterior pelvic exenteration in women and cystoprostatectomy in men may be required due to the aggressive nature of this tumor and the likelihood of recurrence[1,5-7]. Consolidation radiotherapy to the pelvis has been utilized in the treatment of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra when the pelvic lymph nodes are involved[5].

Chemotherapy has been described in the management of urethral carcinoma[24-26], however, a paucity of studies has reported its use in the clear cell variant[7,27]. Gögus and colleagues reported the case of a man with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra who underwent a radical cystoprostatectomy with bilateral inguinal and pelvic lymph node dissection and urethrectomy[27]. Para-aortic lymphadenopathy was noted five months after this surgery which demonstrated tumor metastases on abdominal computed tomography and fine-needle aspiration. He subsequently underwent three cycles of methotrexate-vinblastine-epirubicin-cisplatin chemotherapy but then showed progression and died 10 mo after his surgery. Liedberg and colleagues reported four cases of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the female urethra, two of whom were treated with chemotherapy[7]. After undergoing a cystourethrectomy, one of these patients was treated with adjuvant local radiotherapy and concomitant weekly cisplatin. No evidence of disease was observed at 6-mo follow-up. The other patient underwent an anterior exenteration following which she did not have adjuvant therapy. However, she experienced a locoregional recurrence after 12 mo and received an unspecified chemotherapy. These authors did not provide the chemotherapy outcome. In Dayyani et al[26] study of 44 patients with squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the urethra, the overall response (complete and partial) rate to platinum-containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 72%. This finding suggests that preoperative chemotherapy is associated with prolonged disease-free survival in a subgroup of lymph node positive cases.

Herein, we report the first case in the literature of a patient with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra who underwent personalized chemotherapy testing and was treated successfully with a non-platinum-based chemotherapy. Following 3 cycles of paclitaxel/bevacizumab she attained complete clinical remission, and a PET scan showed a definite improvement in size and metabolic activity in mediastinal, right iliac, obturator, and bilateral inguinal adenopathy. The patient concluded 11 cycles of paclitaxel/bevacizumab, representing a progression-free survival of 12 mo. Lymphedema of the lower extremities was the sole complication.

Individualized medicine through personalized chemotherapy testing offers a unique clinical and therapeutic approach to managing the exceedingly rare clear cell adenoma of the urethra. Our case demonstrates the efficacy of non-platinum-based chemotherapy in the treatment of clear cell adenoma of the urethra. Due to the scarcity of this tumor type, it is difficult to conduct larger studies to establish the safety and efficacy of non-platinum-based chemotherapy. Assessment of the gene alterations in cancer cells can be helpful in selecting systemic treatment for this rare cancer.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report´s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chetty R, Desai DJ S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Alexiev BA, Tavora F. Histology and immunohistochemistry of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: histogenesis and diagnostic problems. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Caplan J, Hartman M, Rooker G. Adenocarcinoma of the female urethra: Clear-cell variant. Radiol Case Rep. 2011;6:490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim TH, Kim SY, Moon KC, Lee J, Cho JY, Kim SH. Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Urethra in Women: Distinctive MRI Findings for Differentiation From Nonadenocarcinoma and Non-Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Urethra. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:805-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mehra R, Vats P, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Udager AM, Roh M, Alva A, Pan J, Lonigro RJ, Siddiqui J, Weizer A, Lee C, Cao X, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Dhanasekaran SM, Chinnaiyan AM. Primary urethral clear-cell adenocarcinoma: comprehensive analysis by surgical pathology, cytopathology, and next-generation sequencing. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Venyo AK. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: review of the literature. Int J Surg Oncol. 2015;2015:790235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bagby CM, MacLennan GT. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the bladder and urethra. J Urol. 2008;180:2656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liedberg F, Gudjonsson S, Håkansson U, Johansson ME. Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Female Urethra: Four Case Presentations of a Clinical and Pathological Entity Requiring Radical Surgery. Urol Int. 2017;99:487-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mallya V, Mallya A, Gayathri J. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra with inguinal lymph node metastases: A rare case report and review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14:468-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oliva E, Young RH. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: a clinicopathologic analysis of 19 cases. Mod Pathol. 1996;9:513-520. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gheiler EL, Tefilli MV, Tiguert R, de Oliveira JG, Pontes JE, Wood DP. Management of primary urethral cancer. Urology. 1998;52:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dancey JE, Bedard PL, Onetto N, Hudson TJ. The genetic basis for cancer treatment decisions. Cell. 2012;148:409-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Han H, Silverman JF, Santucci TS, Macherey RS, d'Amato TA, Tung MY, Weyant RJ, Landreneau RJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer correlates with neoangiogenesis and a poor prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:72-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang SX, Steinberg SM, Nguyen D, Wu TD, Modrusan Z, Swain SM. Gene expression profile and angiogenic marker correlates with response to neoadjuvant bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5893-5899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, Brambilla E, André F, Haddad V, Taranchon E, Filipits M, Pirker R, Popper HH, Stahel R, Sabatier L, Pignon JP, Tursz T, Le Chevalier T, Soria JC; IALT Bio Investigators. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:983-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1319] [Cited by in RCA: 1292] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Steffensen KD, Waldstrøm M, Jakobsen A. The relationship of platinum resistance and ERCC1 protein expression in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:820-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weberpals J, Garbuio K, O'Brien A, Clark-Knowles K, Doucette S, Antoniouk O, Goss G, Dimitroulakos J. The DNA repair proteins BRCA1 and ERCC1 as predictive markers in sporadic ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:806-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, Ashworth A. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4316] [Cited by in RCA: 4855] [Article Influence: 242.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Quinn JE, James CR, Stewart GE, Mulligan JM, White P, Chang GK, Mullan PB, Johnston PG, Wilson RH, Harkin DP. BRCA1 mRNA expression levels predict for overall survival in ovarian cancer after chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7413-7420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Swisher EM, Gonzalez RM, Taniguchi T, Garcia RL, Walsh T, Goff BA, Welcsh P. Methylation and protein expression of DNA repair genes: association with chemotherapy exposure and survival in sporadic ovarian and peritoneal carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dingemans AM, Witlox MA, Stallaert RA, van der Valk P, Postmus PE, Giaccone G. Expression of DNA topoisomerase IIalpha and topoisomerase IIbeta genes predicts survival and response to chemotherapy in patients with small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2048-2058. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Durbecq V, Paesmans M, Cardoso F, Desmedt C, Di Leo A, Chan S, Friedrichs K, Pinter T, Van Belle S, Murray E, Bodrogi I, Walpole E, Lesperance B, Korec S, Crown J, Simmonds P, Perren TJ, Leroy JY, Rouas G, Sotiriou C, Piccart M, Larsimont D. Topoisomerase-II alpha expression as a predictive marker in a population of advanced breast cancer patients randomly treated either with single-agent doxorubicin or single-agent docetaxel. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1207-1214. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Naniwa J, Kigawa J, Kanamori Y, Itamochi H, Oishi T, Shimada M, Shimogai R, Kawaguchi W, Sato S, Terakawa N. Genetic diagnosis for chemosensitivity with drug-resistance genes in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gakis G, Witjes JA, Compérat E, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Lebret T, Ribal MJ, Sherif AM; European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on primary urethral carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;64:823-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, Hanley RS, Girshovich L, Shuster T, Oberfield RA, Zinman L. Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol. 2008;179:536-541; discussion 541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dalbagni G, Donat SM, Eschwège P, Herr HW, Zelefsky MJ. Results of high dose rate brachytherapy, anterior pelvic exenteration and external beam radiotherapy for carcinoma of the female urethra. J Urol. 2001;166:1759-1761. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Dayyani F, Pettaway CA, Kamat AM, Munsell MF, Sircar K, Pagliaro LC. Retrospective analysis of survival outcomes and the role of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with urethral carcinomas referred to medical oncologists. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1171-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gögus C, Baltaci S, Orhan D, Yaman O. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the male urethra. Int J Urol. 2003;10:348-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |