Published online Oct 24, 2020. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i10.836

Peer-review started: June 16, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: July 29, 2020

Accepted: September 11, 2020

Article in press: September 11, 2020

Published online: October 24, 2020

Processing time: 126 Days and 23.2 Hours

Primary small cell of esophageal carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with no established treatment guidelines. A treatment strategy was adopted based on small cell carcinoma of the lung because of many similar clinicopathological features. Here, we report one of the largest case series in a western population.

To review the practice of treating small cell oesophageal cancer (SCOC) with different treatment modalities treated at our institution between 2001 and 2014.

A total of 28 cases of SCOC have been identified. All cases were identified with a ten-digit code known as the CHI number. Data was collected using a combination of an electronic database, case notes and the chemotherapy electronic prescribing system (chemocare). We collected information on age, gender, performance status, staging of the disease (limited stage vs extensive stage).

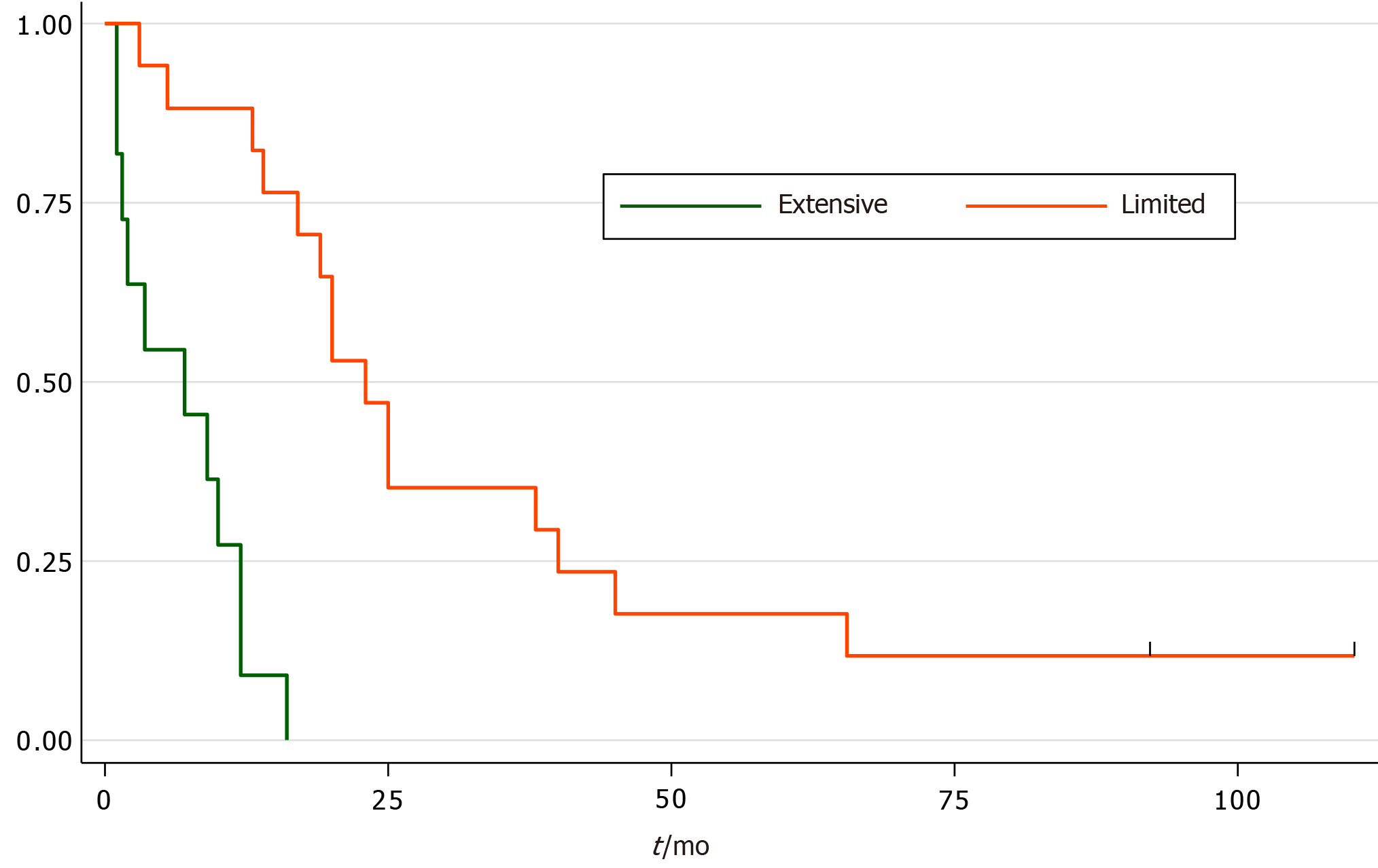

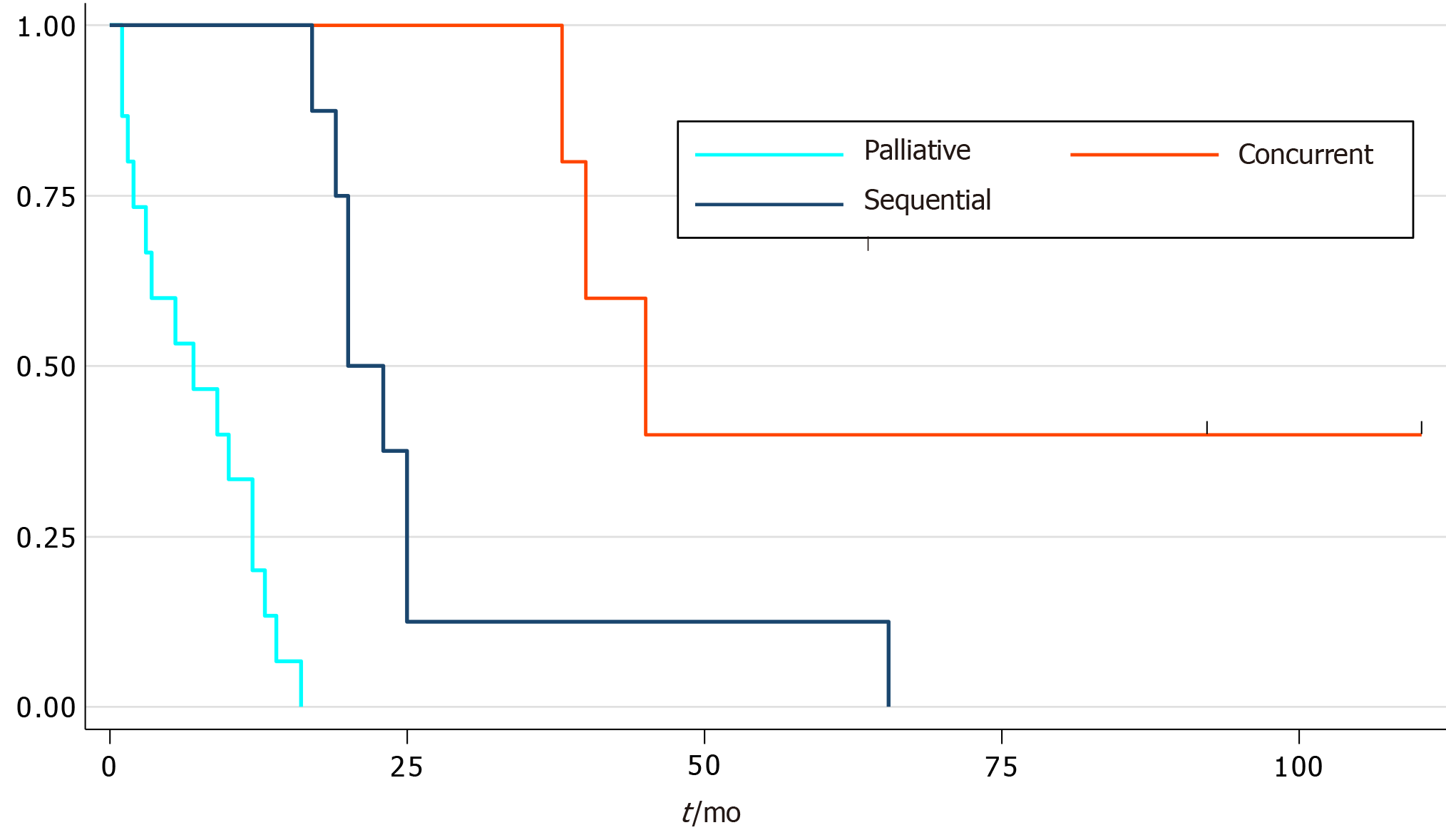

The results showed 17 patients (61%) were diagnosed with limited stage small cell oesophageal cancer (LS-SCOC), while 11 patients (39%) were diagnosed with extensive stage small cell oesophageal cancer (ES-SCOC). The median age at diagnosis of SCOC was 72 years (range 52-86). The median survival for patients with ES-SCOC was 7 mo (95%CI: 1-12) vs LS-SCOC [median 23 mo (95%CI: 14-40)], P < 0.0001. Subgroup analysis of those who received treatment showed the median survival for patients who received palliative chemotherapy was 7 mo (95%CI: 1.5-12), concurrent chemoradiation 45 mo (95%CI: 38-) and sequential chemoradiation 20 mo (95%CI: 17-25), P < 0.0001.

Our data strongly support the use of concurrent chemoradiation in the treatment of LS-SCOC in patients who are fit with no significant comorbidity.

Core Tip: Primary small cell oesophageal carcinoma is rare, prognosis is poor and there is no established optimum treatment strategy. Here, we report largest case series in western world. Our data strongly support the use of concurrent chemoradiation in the treatment of limited stage of small cell carcinoma of the oesophagous in patients who are fit with no significant comorbidity.

- Citation: Alfayez M. Primary small cell oesophageal carcinoma: A retrospective study of different treatment modalities. World J Clin Oncol 2020; 11(10): 836-843

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i10/836.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i10.836

Small cell cancer is a disease characterised by aggressive clinical features, dramatic but often short-lived sensitivity to anti-cancer therapy, and rapid dissemination. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is one of the more common sites of extra-pulmonary small cell cancer[1], and within the GI tract the oesophagus is the organ most frequently affected[2]. Since its first description in 1952[3], only a few hundred cases have been reported, and because of its rarity, consensus on treatment is lacking. Furthermore, no randomised controlled trials have been conducted, however, retrospective cohort studies are reported in the literature. Treatment strategy for small cell carcinoma of the lung has been adopted for oesophageal cancer, as both share many clinical and pathological features. For patients with primary oesophageal small cell cancer in whom there is no evidence of metastatic spread, treatment options include resection[4,5], radiotherapy[6], chemotherapy[7-9] and combination modality treatment[2]. Here, we review the practice of treating small cell oesophageal cancer (SCOC) with different treatment modalities at out institution.

We analysed all cases of SCOC treated at our institution between 2001 and 2014. A total of 28 cases of SCOC have been identified. All cases were identified with a ten-digit code known as the CHI number. Data was collected using a combination of an electronic database, case notes and the chemotherapy electronic prescribing system (chemocare). We collected information on age, gender, performance status, staging of the disease [limited stage (LS) vs extensive stage (ES)]. Further data on treatment modality was also collected. This including palliative chemotherapy, sequential chemoradiation (chemotherapy followed by consolidation radiotherapy), or concurrent chemoradiation. None of the patients had surgical resection as primary modality of treatment. Staging was used similar to the staging used in small cell lung cancer. LS is defined as when the tumour is encompassed within a safe and a tolerable radiation field. ES is when the disease is too widespread to be treated within one safe and tolerable radiation field. All patients had a confirmed histological diagnosis of SCOC from an upper gastrointestinal endoscopic biopsy as well as staging with a computed tomography (CT) for chest, abdomen and pelvis. The middle oesophageal tumour is defined endoscopically between 24 cm to 32 cm from incisors while lower oesophageal tumour is defined 32-40 cm from incisors.

None of the patients underwent a CT head scan as part of the staging process. None of the patients had positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). The diagnosis of SCOC was made based on classical cellular morphology as well as immunohistochemistry staining. All cases were discussed at regional multidisciplinary team meeting before starting their treatment. Information on date of death was obtained via survival analysis undertaken by the Information Service Division of NHS Scotland. Death records were complete until 1 February 2015, which served as the censor date for those alive.

Seventeen patients (61%) were diagnosed with limited stage small cell oesophageal cancer (LS-SCOC), while 11 patients (39%) were diagnosed with extensive stage small cell oesophageal cancer (ES-SCOC). Four patients diagnosed with LS-SCOC had mixed pathology, three of them diagnosed with small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, while one patient had LS-SCOC mixed with squamous cell carcinoma.

The median age at diagnosis of SCOC was 72 years (range 52-86), and it appeared to be more common in men (57%) than in women. The tumour is more likely to be located in the lower part of the oesophagus (82%) than in the middle (Table 1). No upper oesophageal SCOC has been recorded.

| Characteristic | All patients (28) | Palliative chemotherapy (15) | Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (5) | Sequential chemoradiotherapy (8) |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| Median | 72 | 72 | 79 | 70 |

| Range | 52-86 | 53-86 | 58-83 | 52-78 |

| Performance status of 0 or 1 (%) | 82 | 67 | 100 | 100 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (%) | 57 | 53 | 100 | 38 |

| Female (%) | 43 | 47 | None | 62 |

| Tumour Stage | ||||

| Limited (%) | 60 | 27 | 100 | 100 |

| Extensive (%) | 40 | 73 | None | None |

| Location of the tumour | ||||

| Mid-oesophagus (%) | 18 | 27 | None | 13 |

| Low-oesophagus (%) | 82 | 73 | 100 | 87 |

Two patients (7%) diagnosed with ES-SCOC did not receive any treatment, while eight patients received platinum-based palliative chemotherapy (Table 2). The overall median survival for ES-SCOC was 7 mo (95%CI: 1-12, Figure 1). Three patients with ES-SCOC were found to have brain metastasis, two them did not receive chemotherapy. Four patients who were treated with palliative chemotherapy went onto have a palliative dose of radiotherapy to the oesophagus of 20 Gray (Gy) in five fractions (Table 2).

| Patient | Age | Sex | PS | Stage | Site | CT | Cycles (n) | Palliative RT | Response | Survival (mo) |

| 1 | 80 | M | 1 | ES | Low | PE | 6 | No | PR | 16 |

| 2 | 58 | M | 1 | ES | Low | PE | 6 | No | PR | 12 |

| 3 | 67 | F | 2 | ES | Mid | P | 4 | No | PR | 9 |

| 4 | 80 | M | 3 | ES | Mid | P | 2 | No | UK | 1.5 |

| 5 | 59 | M | 1 | ES | Mid | PE | 2 | Yes | UK | 2 |

| 6 | 70 | F | 1 | ES | Low | PE | 4 | Yes | PR | 12 |

| 7 | 53 | F | 0 | ES | Low | CE | 6 | No | PR | 10 |

| 8 | 62 | F | 2 | ES | Mid | P | 4 | No | PR | 7 |

| 9 | 65 | M | 0 | ES | Low | PE | 4 | No | PR | 3.5 |

| 10 | 81 | F | 3 | ES | Low | None | 0 | No | NA | 1 |

| 11 | 84 | F | 2 | ES | Low | None | 0 | Yes | NA | 1 |

| 12 | 86 | M | 1 | LS | Low | P | 2 | Yes | SD | 14 |

| 13 | 75 | M | 1 | LS | Low | PE | 4 | No | PR | 3 |

| 14 | 72 | M | 0 | LS | Low1 | ECX/CE | 3/3 | No | SD | 13 |

| 15 | 75 | F | 1 | LS | Low | PE | 2 | No | PR | 5.5 |

Four patients with LS-small cell of esophageal carcinoma received platinum-based chemotherapy. One patient with mixed pathology of SCOC and squamous cell carcinoma had three cycles of ECX (epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine) followed by three cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy. The median survival for that patient was 13.3 mo (Table 2).

Five patients received concurrent chemoradiation. Five weeks of radiotherapy, as part of the concurrent chemoradiation regimen, was provided after two cycles of induction platinum-based chemotherapy. This was delivered concurrently with one to two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy. The dose of radiotherapy was 4000-5000 cGy.

Eight patients received sequential chemoradiotherapy. Radiotherapy as part of sequential chemoradiotherapy was administered three to five weeks after the last cycle of chemotherapy, with the dose given being 4005-5000 cGy. No prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) was given to any patients. None of the patients who were treated radically were found to have any brain metastases (Table 3).

The overall median survival of the LS-SCOC patients was 23 mo (95%CI: 14-40, Figure 1). Subgroup analysis showed survival of patients who received sequential chemoradiotherapy, and those who received concurrent chemoradiation, was 20 mo (95%CI: 17-25) and 45 mo (95%CI: 39-) respectively (Figure 2).

Two patients with ES-SCOC who progressed shortly after first line chemotherapy were determined fit enough and managed to receive two to three cycles of second line chemotherapy with a combination of the chemotherapy drugs cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine (CAV). Both patients progressed on while receiving CAV chemotherapy (two to three cycles). The experience with second-line chemotherapy in patients diagnosed with LS-SCOC was variable. Among those that received sequential chemoradiation, only three out of five patients who received second line chemotherapy were re-challenged with platinum-based chemotherapy (Table 4). None of the patients who had been treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy had received second-line chemotherapy.

| Patient | Age | Sex | PS | Site | CT | Cycles (n) | RT dose | Response | Site ofrelapse | 2nd Line CT | Survival(mo) |

| 1 | 52 | F | 0 | Mid | CE | 6 | 50 Gy in 20 Fr | CR | Liver | 2 Top | 25 |

| 2 | 78 | F | 0 | Low | PE | 1 | 50 Gy in 20 Fr | CR | UK | None | 25 |

| 3 | 71 | M | 0 | Low | CE/PE | 3 | 50 Gy in 20 Fr | CR | Local | 6 PE | 23 |

| 4 | 70 | M | 1 | Low1 | PE | 5 | 50 Gy in 20 Fr | PR | Local | 2 PE | 20 |

| 5 | 67 | F | 1 | Low | CE | 4 | 45 Gy in 25 Fr | PR | Local2 | 3 ECX | 65.5 |

| 6 | 70 | F | 1 | Low | CE | 4 | 50 Gy in 20 Fr | UK | UK | None | 19 |

| 7 | 73 | F | 1 | Low | PE | 4 | 4005 cGy in 15 Fr | PR | UK | None | 17 |

| 8 | 69 | M | 1 | Low1 | PE | 5 | 50 Gy in 25 Fr | PR | UK | 2 PE | 20 |

Primary SCOC is an uncommon cancer, and here we report one of the largest case studies in a Western population. The clinical features of our patients with SCOC and its distribution are similar to most studies in the literature[10]. Specifically, we describe a male: Female ratio of 1.33:1, with all tumours arising from the mid- to lower-oesophagus.

Four cases out of 28 (14%) had mixed pathology with the reminder 24 (86%) cases having a pure variant of small cell carcinoma. Comparable findings were reported in a recent meta-analysis[11]. Whilst the prognosis for many patients with the more typical oesophageal squamous or adenocarcinoma is often poor, small cell cancers are particularly associated with rapid growth, early dissemination, and a resultant poor prognosis with a typical median overall survival of 12 mo in the recent published meta-analysis[11].

The role of surgical resection in patients with SCOC is still not proven with outcomes remaining unfavourable. Primary surgery with or without adjuvant treatment has elicited poor outcomes[12-14] with a median survival in a number of surgical resection series is less than 12 mo[12].

There is a general consensus that systemic chemotherapy should also be used in the treatment of small cell carcinoma of any primary site because of the high likelihood of early dissemination. It may be appropriate to extrapolate the data from small cell carcinoma of the lung to SCOC. In our case series, patients with ES-SCOC treated with systemic treatment had only a median survival time of nine months. Similar findings have been reported from a case series in the United Kingdom[15]. The treatment of choice in the first-line setting is platinum-based chemotherapy. The treatment choice for second-line chemotherapy is variable. However, extrapolating from small cell carcinoma of the lung, for late relapse (> 6 mo), it is reasonable to consider retreatment with platinum-based chemotherapy[16]. In our case series, all patients received platinum based chemotherapy as their first line chemotherapy here, such chemotherapy was administered to all patients that received active treatment. Only eight out of 25 patients (32%) were given second-line chemotherapy.

In contrast to systemic treatment, radiotherapy alone has not been widely used[15]. None of the patients presented in our series had primary radiotherapy as the sole treatment. However, radiotherapy has been used previously either to consolidate the primary site sequentially after systemic treatment or concurrently with chemotherapy. In our series sequential chemoradiotherapy has a median survival time of 23 mo (95%CI: 17.5-27.8). This is compatible with Hudson et al[15]’s case series.

There have recently been favourable reports of chemoradiotherapy as the sole treatment of SCOC[13]. Unfortunately, there are no randomised controlled trials to support its use. The results presented in our case series suggest that treating patients with LS-SCOC with concurrent chemoradiation yields the longest median survival time of 45 mo (95%CI: 34.5-55.3). Although we recognise it is difficult to draw conclusions from this given there were so few patients involved. Furthermore, our data suggested re-biopsy of the local recurrence is warranted as a new primary tumour at the local site is a possibility.

In our cohort, one patient treated with concurrent chemoradiation had an initial biopsy that was compatible with a carcinoma demonstrating mixed squamous and small cell features. Upon completion of treatment, repeat endoscopic and radiologic assessment revealed no evidence of residual tumour or metastatic disease. The patient remained well for three years before presenting with fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. Investigations at this time demonstrated liver metastases. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of one of the liver lesions uncovered features of recurrent squamous cancer with no evidence of a residual neuroendocrine element. No further treatment was provided and the patient subsequently died two months later, 38 mo after diagnosis.

Another patient who diagnosed with pure SCOC treated with concurrent chemoradiation, remained well (with negative endoscopic/histological findings) until the development of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux 21 mo after completion of CRT. Endoscopy demonstrated minor oesophagitis with no macroscopic tumour evident, through biopsies of this area revealed the presence of a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent salvage oesophagostomy and recovered very well from the operation, continuing to be alive today.

PCI has been shown to improve survival, as well as local control, in small cell carcinomas of the lung[17,18]. The role of PCI in patients with SCOC is unclear. None of the patients presented in this series with LS had a relapse in the brain. We think It is therefore reasonable to omit PCI in patients with SCOC, consistent with a previous case series report[15]. One of the drawback of the study is no robust collection of treatment toxicity.

In conclusion, tumours such as SCOC provide treatment challenges because of the lack of RCT evidence. However, our data strongly support the use of concurrent chemoradiation in the treatment of LS-SCOC in patients who are fit with no significant comorbidity. Those patients have a better survival compared to the rest of the other groups. Further, PCI can be safely omitted in this group.

Small cell oesophageal cancer (SCOC) is rare. Until now, there was no general consensus of optimal treatment in this group of patients.

Future RCT involving this small group population is a priority to determine best modality of treatment.

The main objective was to determine the best modality of treatment for patients diagnosed with SCOC.

This is a retrospective analysis of different treatment modalities on this highly poor prognosis as well as a rare group of esophageal carcinoma.

The finding of this study will add to growing body of literature on the benefit of CCRT in the treatment of limited stage (LS) small cell cancer of esophagus.

Patient with LS of oesophageal cancer with good performance status should be treated with Concurrent chemoradiation.

The future research will involve prospective studies.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Que J S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Haider K, Shahid RK, Finch D, Sami A, Ahmad I, Yadav S, Alvi R, Popkin D, Ahmed S. Extrapulmonary small cell cancer: a Canadian province's experience. Cancer. 2006;107:2262-2269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huncharek M, Muscat J. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. The Massachusetts General Hospital experience, 1978 to 1993. Chest. 1995;107:179-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mckeown F. Oat-cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:889-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yachida S, Matsushita K, Usuki H, Wanibuchi H, Maeba T, Maeta H. Long-term survival after resection for small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:596-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nishimaki T, Suzuki T, Nakagawa S, Watanabe K, Aizawa K, Hatakeyama K. Tumor spread and outcome of treatment in primary esophageal small cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1997;64:130-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nemoto K, Zhao HJ, Goto T, Ogawa Y, Takai Y, Matsushita H, Takeda K, Takahashi C, Saito H, Yamada S. Radiation therapy for limited-stage small-cell esophageal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:404-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kelsen DP, Weston E, Kurtz R, Cvitkovic E, Lieberman P, Golbey RB. Small-cell carcinoma of the esophagus: treatment by chemotherapy alone. Cancer. 1980;45:1558-1561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tanabe G, Kajisa T, Shimazu H, Yoshida A. Effective chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1987;60:2613-2616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Okuma HS, Iwasa S, Shoji H, Takashima A, Okita N, Honma Y, Kato K, Hamaguchi T, Yamada Y, Shimada Y. Irinotecan plus cisplatin in patients with extensive-disease poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:5037-5041. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Casas F, Ferrer F, Farrús B, Casals J, Biete A. Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a review of the literature with emphasis on therapy and prognosis. Cancer. 1997;80:1366-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al Mansoor S, Ziske C, Schmidt-Wolf IG. Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: patient data metaanalysis and review of the literature. Ger Med Sci. 2013;11:Doc12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Law SY, Fok M, Lam KY, Loke SL, Ma LT, Wong J. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1994;73:2894-2899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang HH, Zaorsky NG, Meng MB, Wu ZQ, Zeng XL, Jiang B, Jiang C, Zhao LJ, Yuan ZY, Wang P. Multimodality therapy is recommended for limited-stage combined small cell esophageal carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:437-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hosokawa A, Shimada Y, Matsumura Y, Yamada Y, Muro K, Hamaguchi T, Igaki H, Tachimori Y, Kato H, Shirao K. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Analysis of 14 cases and literature review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1738-1741. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hudson E, Powell J, Mukherjee S, Crosby TD, Brewster AE, Maughan TS, Bailey H, Lester JF. Small cell oesophageal carcinoma: an institutional experience and review of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:708-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Postmus PE, Berendsen HH, van Zandwijk N, Splinter TA, Burghouts JT, Bakker W. Retreatment with the induction regimen in small cell lung cancer relapsing after an initial response to short term chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:1409-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Slotman B, Faivre-Finn C, Kramer G, Rankin E, Snee M, Hatton M, Postmus P, Collette L, Musat E, Senan S; EORTC Radiation Oncology Group and Lung Cancer Group. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:664-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 768] [Cited by in RCA: 751] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aupérin A, Arriagada R, Pignon JP, Le Péchoux C, Gregor A, Stephens RJ, Kristjansen PE, Johnson BE, Ueoka H, Wagner H, Aisner J. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:476-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1224] [Cited by in RCA: 1152] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |