Published online Jan 24, 2020. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i1.11

Peer-review started: March 11, 2019

First decision: April 15, 2019

Revised: October 14, 2019

Accepted: November 5, 2019

Article in press: November 5, 2019

Published online: January 24, 2020

Processing time: 292 Days and 22.3 Hours

AiCC is a primarily indolent disease process. Our aim with this study is to determine characteristics consistent with rapidly progressive AiCC of the parotid gland.

To report on patients with metastatic lung disease from AiCC and potential correlative factors.

Single-institution retrospective review of patients treated at the University of Michigan between 2000 and 2017. Univariate analyses were performed.

A total of 55 patients were identified. There were 6 patients (10.9%) with primary AiCC of the parotid gland who developed lung metastases. The mean age at diagnosis for patients with lung metastases was 57.8 years of age, in comparison to 40.2 years for those without metastases (P = 0.064). All 6 of the patients with lung metastases demonstrated gross perineural invasion intraoperatively, in comparison to none of those in the non-lung metastases cohort. Worse disease-free and overall survival were significantly associated with gross perineural invasion, high-grade differentiation, and T4 classification (P < 0.001).

AiCC of the parotid gland is viewed as a low-grade neoplasm with good curative outcomes and low likelihood of metastasis. With metastasis, however, it does exhibit a tendency to spread to the lungs. These patients thereby comprise a unique and understudied patient population. In this retrospective study, factors that have been shown to be statistically significant in association with worse disease-free survival and overall survival include presence of gross facial nerve invasion, higher T-classification, and high-grade disease.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study to evaluate clinical outcomes in patients with primary acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland treated at a tertiary care medical center. Among 55 primary cases, 6 patients developed lung metastases. These patients uniformly demonstrated gross facial nerve invasion intraoperatively. Additional factors that were associated with worse disease-free survival and overall survival included higher T-classification and high-grade disease on pathology.

- Citation: Ali SA, Kovatch KJ, Yousif J, Gupta S, Rosko AJ, Spector ME. Predictors of distant metastasis in acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. World J Clin Oncol 2020; 11(1): 11-19

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i1/11.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i1.11

Salivary gland tumors comprise a rare disease process in which malignant cells form in the tissues of the minor and major salivary glands. These can be subdivided into epithelial and non-epithelial neoplasms, approximately 95% of which are epithelial. Approximately 90% of primary epithelial salivary gland tumors occur in the parotid gland; the remainder occur in submandibular, sublingual and other minor salivary glands. The rate of malignancy in each salivary gland is inversely correlated with the size of the salivary gland; approximately 20%-25% parotid gland tumors are malignant in comparison to 60%-80% of minor salivary gland tumors[1]. Amongst primary parotid gland malignancies, acinic cell carcinoma (AiCC) accounts for 1% to 6% of all epithelial salivary gland tumors and 10%-15% of all primary parotid malignant tumors[2]. It is typically diagnosed by pathology, as it can easily be mistaken clinically or radiologically for a different disease process[3].

AiCC is considered a low-grade, indolent salivary gland carcinoma with cure rate of 89% at 5 years[4]. High-grade transformation, formerly known as de-differentiation, is a rarely recognized event in AiCC that has been increasingly reported in the past 10-15 years[5]. A large National Cancer Database (NCDB) study performed by Xiao et al[6] found that amongst eight identified histopathologies, AiCC demonstrated positive clinical nodal disease in 10% of cases and occult positive nodal disease in 4.4% of cases. Further, high-grade differentiation was significantly predictive for nodal metastasis and worse overall survival in AiCC. Cases of AiCC with distant metastases are largely reported in case reports and smaller case series in the literature, with such studies identifying higher stage, presence of lymph node involvement, lymphovascular invasion and perineural invasion (PNI) as possible predictive characteristics[1]. While surgical excision is well-established for low-grade tumors with favorable pathologic characteristics, the treatment paradigm for high-grade malignancies is less well-defined. The majority of studies describe treatment with surgery and adjuvant radiation therapy, with occasional implementation of chemotherapy[7]. Treatment planning is of particular importance as a small subset of patients with high-grade tumors have shown propensity to develop lung metastases (LM). Thus, identification of primary tumor characteristics that predispose patients to developing distant metastases is crucial for appropriate surveillance and adjuvant considerations for this unique patient population.

Our primary goal was to examine the incidence of lung metastasis in our cohort of patients with AiCC. We aimed to assess demographic, histopathologic and clinical factors that may indicate increased risk of developing LM in this cohort.

We performed an IRB-approved single-institution retrospective case series of patients with AiCC of the parotid gland. Patients who underwent parotidectomy (superficial or total) for treatment of AiCC between 2000-2017 were included. Specifically, those who underwent primary surgical treatment at our institution were included. Patients who did not undergo parotidectomy as initial therapy were excluded from the study, as were patients who underwent initial surgery at a separate institution. Patients who presented with distant metastases at initial presentation were excluded. Demographics, clinical and pathologic T-, N-, and M-classifications, overall stage, primary treatment modality, histopathologic characteristics, mortality and recurrent-specific data were tabulated. Data were collected using clinical notes, pathology reports, and imaging available in our electronic medical records system. Patients were staged in accordance with the 7th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System[8].

Bivariate associations between clinical variables were tested with nonparametric tests (i.e., Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test with Monte Carlo estimates for error terms). SPSS version 22 software (IBM; Armonk, NY, United States) was used to perform statistical analyses. All statistical tests of significance were two-sided with α of 0.05. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate curves for disease-free survival and overall survival.

Fifty-five total patients with AiCC were evaluated. Patient demographic information is available in Table 1 and delineates patient cohorts with and without LM. There were 6 out of 55 (10.9%) total patients who developed LM in our cohort. Median follow-up time was 47 mo (range 1-172 mo).

| Characteristic | Patients with lung metastases (n = 6) | Patients without lung metastases (n = 49) | P value |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 57.8 | 40.2 | 0.064 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 5 (83.3) | 21 (42.9) | |

| Female | 1 (16.7) | 28 (57.1) | |

| Parotidectomy type | 0.00013 | ||

| Superficial | 1 (16.7) | 39 (79.5) | |

| Total | 5 (83.3) | 10 (20.4) | |

| Neck dissection | 3 (50.0) | 7 (14.3) | 0.08 |

| Positive margins | 1 (16.7) | 6 (12.2) | 0.77 |

| Gross nerve invasion | 6 (100) | 0 | < 0.0001 |

| Greatest dimension | 5.20 cm | 2.58 cm | < 0.0001 |

| Initial overall stage | |||

| I | 0 | 21 (42.8) | |

| II | 0 | 19 (38.7) | |

| III | 0 | 06 (12.2) | |

| IV | 6 (100) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Unknown | |||

| Initial T-stage | |||

| T1 | 0 | 24 (48.9) | |

| T2 | 0 | 18 (36.7) | |

| T3 | 0 | 6 (12.2) | |

| T4 | 6 (100) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Tx | 0 | 0 | |

| Initial nodal status | |||

| N0 | 5 (83.3) | 47 (95.9) | |

| N1 | 0 | 1 (2.0) | |

| N2 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (2.0) | |

| N3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nx | 0 | 0 | |

| High-grade | 3 (50) | 1 (2.0) | 0.019 |

| Adjuvant XRT | 5 (83.3) | 14 (28.6) | < 0.001 |

Patients with LM presented with larger overall tumors as demonstrated on surgical pathology, with a greatest size of 4.32 cm in comparison to 2.57 cm in the non-LM cohort. There were no patients in the study who presented preoperatively with clinically detectable facial nerve weakness. Overall staging was on average greater for patients in the LM cohort with all six patients with stage IV disease. In comparison, 82% (n = 40) of the non-LM cohort had overall stages of I or II. All of the LM patients had at least T4a classification given presence of gross facial nerve invasion. The average T-classification comparison between the groups was significant (P < 0.0001), with 2 patients in the non-LM cohort with stage IV disease. Both patients had T4a classification due to skin invasion that was resected at the initial operation. They both required free tissue transfer for reconstruction and received post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy Few patients had nodal disease. Only one patient in the LM cohort had positive nodal disease on final pathology from their initial operation, in comparison to 2 (4.1%) of the non-LM cohort. All 6 of the patients in the LM cohort had gross facial nerve invasion, in comparison to none of the patients in the non-LM group (P < 0.0001).

Patient characteristics for LM patients is available in Table 2. Those with LM were on average older in age (57.8 years) compared to those without LM (40.2 years). Five out of six (83.3%) of patients with LM were male. Three of the patients in the LM cohort experienced isolated distant spread to the lungs. While six of the patients in the non-LM cohort experienced local recurrence, none of them experienced regional recurrence. Eighty-three percent of the patients (n = 5) in the LM cohort underwent adjuvant radiation therapy, in comparison to 29% (n = 14) of patients in the non-LM cohort. The remaining patient refused radiation treatment. Three of the patients in the LM group underwent chemotherapy as primary modality of treatment for their recurrent cancer.

| Patient characteristics | Grade | T-classification | Facial nerve invasion | Recurrence sites |

| 63 yr Male | High | T4a | Yes | Local, distant (lungs) |

| 77 yr Female | Low | T4a | Yes | Distant (lungs) |

| 44 yr Male | High | T4a | Yes | Distant (lungs) |

| 52 yr Male | High | T4a | Yes | Distant (lungs) |

| 71 yr Male | Low | T4a | Yes | Regional, distant (lungs) |

| 40 yr Male | Low | T4a | Yes | Local, regional, distant (lungs) |

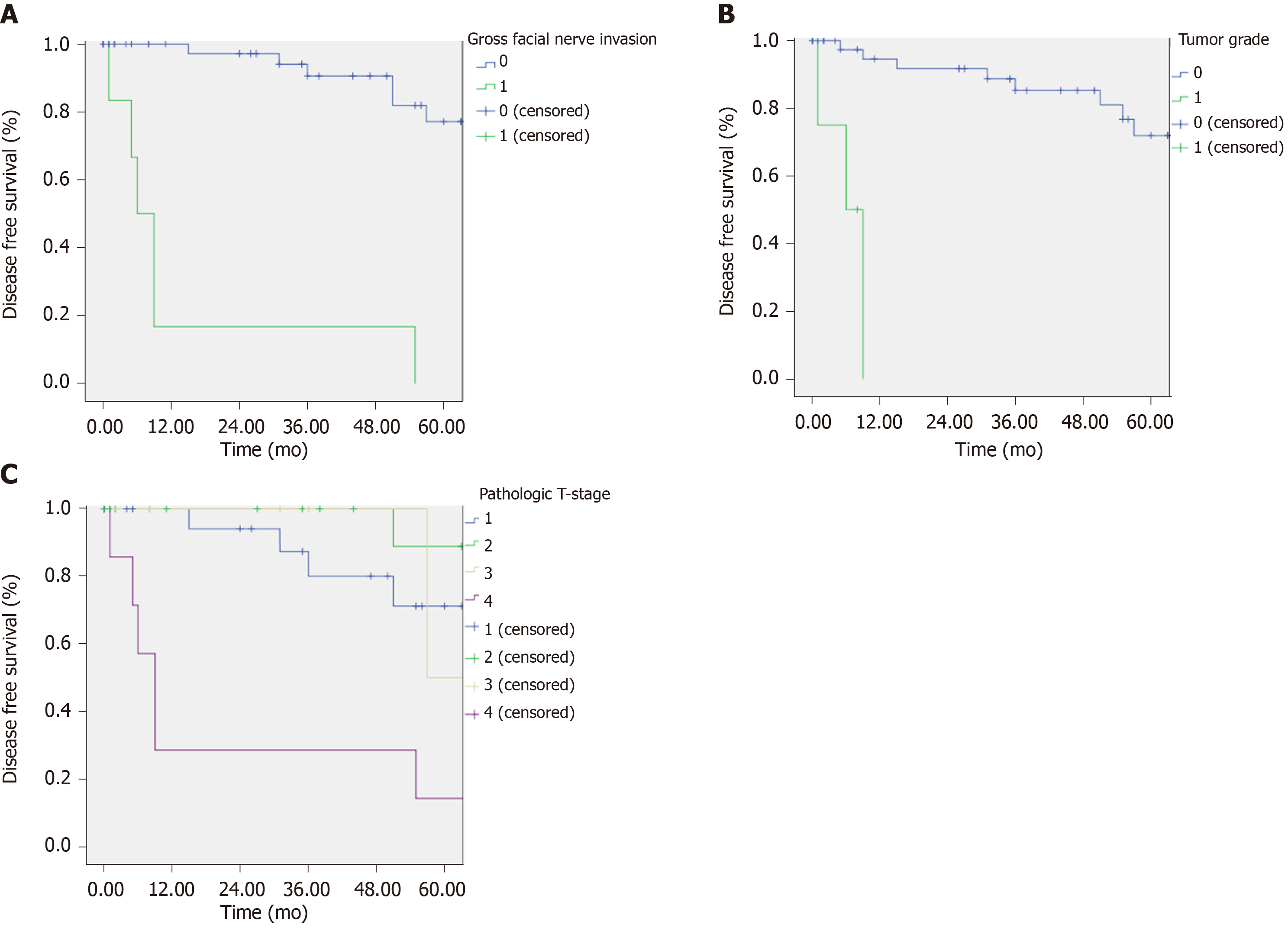

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for disease-free survival and overall survival. In a univariate analysis, there were significant differences in the survival of patients who had T4 disease, high-grade differentiation, and the presence of gross facial nerve invasion (Figure 1). Positive margins and N-stage were not associated with disease-free survival. Additionally, there were significant differences in the overall survival of patients who had high-grade differentiation tumors and gross facial nerve invasion (P < 0.001). Overall survival was also worse in patients with at least T4 classification in comparison to those with lower T-classification.

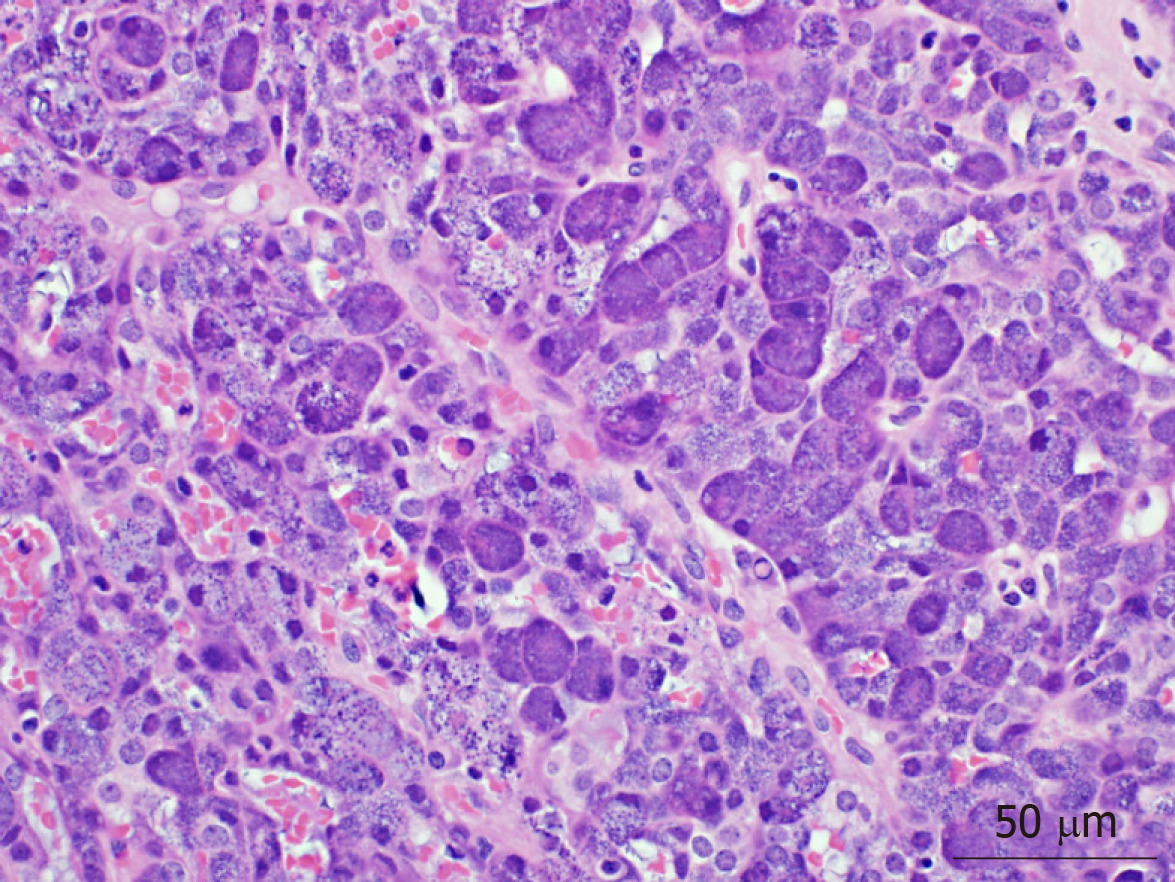

AiCC has historically been considered an indolent tumor, with the literature commonly referring to it as a good actor in overall salivary gland carcinoma. Within the last 15 to 20 years, there have been increasing reports of high-grade transformation in these tumors, the sequelae of which include greater risk of recurrence and metastasis, as well as reduced overall survival. While clinical and pathologic factors that portend poor disease-free survival and overall survival are well-characterized, there is a paucity of information regarding factors correlative with distant metastases in this patient population. In this retrospective review, clinical and pathologic data from 55 patients with primary AiCC of the parotid gland were analyzed. Six patients (10.9%) developed distant metastases, all of which involved the lungs. Advanced T-classification (particularly T4), high-grade differentiation, and gross facial nerve invasion were all implicated in shorter disease-free survival; high-grade differentiation on pathology is demonstrated in Figure 2. These data suggest that patients with these high-risk characteristics, and no evidence of distant disease on presentation, may warrant consideration for additional imaging for screening purposes.

For a relatively rare pathologic classification of head and neck cancer, salivary gland malignancies demonstrate remarkable variability in their pattern and propensity for distant spread. Overall, approximately 20% of salivary gland malignancies will develop distant metastasis (DM), with high-grade pathologies demonstrating significantly greater propensity for DM[9]. Among salivary gland malignancies, salivary ductal carcinoma has demonstrates the highest rate of distant spread, with DM reported in as high as 57%-82% of patients[9]. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, particularly the solid histopathologic type, demonstrates reported rates of DM ranging from 25% to 38%[10]. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, while considered a better actor in terms of DM, demonstrated rates of 16.3% in one large retrospective review[11]. Indeed, propensity toward distant spread is greater in lesions of intermediate and high-grade, in comparison to low-grade pathologic types. Myoepithelial carcinoma demonstrated the lowest rates of DM in a large single-institution study at 6% (one out of sixteen patients)[12]. Typical time to detection of DM also varies significantly amongst salivary gland malignancies. In adenoid cystic carcinoma, time to development of DM is approximately 3 years, although metastatic disease developing as late as nearly 10 years after initial diagnosis have been reported[13]. Salivary ductal carcinoma, on the other hand, tends to present more often with DM and rarely do patients develop late distant spread[14]. The most common sites for DM in salivary gland tumors include the lungs, bone, and liver; approximately one-half of all cases with distant spread will include LM[9].

Our AiCC cohort had a rate of DM of 10.9% at a mean latency of 17.8 mo (median follow-up 47 mo). A large retrospective study of AiCC from the Mayo Clinic demonstrated that 20.6% of their cohort developed DM[15]. Median time to development of DM was 3 years, with one outlier demonstrating distant spread nearly 30 years following initial diagnosis. The lungs are among the most commonly described sites of DM, although spread to the liver and to various bony anatomic sites have also been reported in various case reports and series[1].

There are a few larger retrospective reviews in the literature that discuss factors predictive of poor prognosis in patients with AiCC. In regards to demographic and clinical features, pain, older age, male gender, mass fixation, African-American race, facial palsy and short duration of symptoms are associated with poor prognosis[15,16]. Additional pathologic features that relate to poor prognosis microscopic features of desmoplasia, atypia or increased mitotic activity, and invasion of the lateral skull base[15,16]. In a large NCDB report, Hoffman et al[17] identified higher grade, regional or DM at presentation, and age greater than 30 years to be significantly associated with worse disease-specific survival. A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry based study of 1129 cases demonstrated that patients with poorly differentiated tumors and those with DM had very poor 20-year survival rates[18]. A retrospective review from Beijing demonstrated that pathologic characteristics of high-grade differentiation, nodal stage, presence of PNI and ALI were associated with worse overall survival and disease-free survival[19]. In a smaller clinical analysis on AiCC, 3 out of 20 analyzed patients who developed DM were described to have more aggressive clinical features, although these were not specified in the study[20]. In a clinicopathologic review of 25 patients, Thompson et al[21] demonstrated that high-grade transformation in AiCC was associated with a high rate of DM. A large retrospective review from Brazil on major salivary gland carcinomas demonstrated that clinical stage, positive lymph nodes, facial paralysis and invasion of adjacent structures were predictors of DM[12]. The study is limited in application to our discussion, as there were only 17 patients with AiCC, 2 of whom developed DM.

In our cohort, we identified 55 patients who underwent superficial or total parotidectomy for AiCC from 2000 to 2016. Amongst those, we identified 6 patients who developed LM. Factors that correlated with DM in our patient cohort included T4 classification, high-grade differentiation and presence of gross facial nerve invasion. Factors of older age, positive nodal status, positive margins were not found to be associated with DM in our population. This may be secondary to the smaller natures of our study. Given its overall indolent nature, the vast majority of patients with AiCC will have low-grade differentiation (93% of patients in our cohort, Figure 3). Six (100%) of LM patients demonstrated evidence of gross facial nerve invasion intra-operatively, necessitating sacrifice of various branches of the facial nerve. Interestingly, none of these patients demonstrated pre-operative facial nerve weakness, perhaps indicating that preoperative testing may not be helpful in assessing for possible gross nerve invasion intraoperatively. None of the non-LM cohort exhibited facial nerve invasion on pathology. Indeed, nerve invasion is considered a poor prognostic marker in many other the subtypes of cancers of the head and neck and may be predictive of distant metastases in patients with AiCC specifically.

On average, the non-LM cohort was younger (40.2 vs 57.8). This is consistent with previous finding by Neskey et al[22] that earlier age of presentation, specifically age < 45, is significantly associated with improved survival. This group also found that larger primary lesions, specifically tumors larger than 3 cm were significantly associated with decreased overall survival, consistent with the findings in our study, where all patient presenting with LM had primary tumors of 4 cm or greater.

While this study is limited by the low overall incidence of AiCC and commensurate low overall rates of distant metastases, when examined in context with larger database-driven reports there is evidence of potential important predictors of distant metastases. In particular, patients with higher T-classification, high-grade differentiation and presence of gross facial nerve invasion may warrant consideration for heightened surveillance with screening for metastasis. Considerations for heightened surveillance could include greater attention paid to pulmonary signs and symptoms, as well as more frequent utilization of chest imaging. Further study is needed to determine the clinical utility of routine screening by chest x-ray or chest CT for high risk patients. Future studies could follow high-risk patients in a longitudinal fashion to determine propensity for development of LM. Analyzing tumor specimens from patients who developed LM for molecular biomarkers could potentially lead to the discovery of actionable or predictive targets.

In conclusion, AiCC of the parotid gland is widely viewed as a low-grade neoplasm with good curative outcomes and low likelihood of metastasis. With metastasis, however, this pathology does exhibit a tendency to spread to the lungs. These patients thereby comprise a unique and understudied patient population. This study suggests that patients with the identified high-risk characteristics, specifically advanced T-stage and gross facial nerve invasion, may warrant higher suspicion and heightened surveillance for metastatic lung disease.

AiCC is regarded as a low-grade, indolent primary cancer of the salivary gland. There are few reports in the literature of high-grade AiCC or instances of distant metastases.

This study aims to further identify potential predictors of distant metastases in this predominantly low-grade carcinoma. This will allow us to identify patients at risk for distant metastases and those who should be closely followed after treatment.

The main objective was to identify predictors of distant metastases in patients with AiCC of the parotid gland. We were able to identify gross facial nerve invasion as a unique predictor. Realizing this objective will allow us to sequence tissue from these poorly behaving carcinoma specimens and potentially identify actionable targets.

The research methods for this study involved utilizing a thorough search via high-yield keywords and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to identify all patients with AiCC treated at the study institution. Further narrowing and identification of the final dataset was undertaken through manual means.

This study identified gross facial nerve invasion as an intra-operative predictor of distant metastases in patients with AiCC of the parotid gland. Additional factors that were associated with worse disease-free survival and overall survival included higher T-classification and high-grade disease on pathology. Further studies could sequence specimens from these patients and determine possible contributing mutations or biomarkers.

This study determines that gross facial nerve invasion is an intraoperative predictor of distant metastases in patients with AiCC of the parotid gland. Patients with gross facial nerve invasion should be carefully followed and potentially screened for distant metastases as part of their post-treatment surveillance. High-grade pathology and greater T-stage are associated with worse disease-free and overall survival in this patient population. Intraoperative findings a supplement pathologic findings in determining post-operative treatment plans and need for additional screening or follow-up. The new hypothesis proposed is the potential for additional predictors of poor outcomes in a largely low-grade and indolent carcinoma. This study utilized extensive keyword and ICD code-based review of a single-insitution’s database. Gross facial nerve invasion is found to be predictive of distant metastases in AiCC of the parotid gland. This study confirmed our hypothesis that there are additional predictive clinical factors in patients with AiCC who develop distant metastases. This study can help identify patients who may benefit from closer dedicated follow-up or additional screening.

Despite previous literature and similarly sized retrospective reviews, there can be additional useful information available in performing similar retrospective studies. Future research must take place on the basic science or translational level. This could entail sequencing tumor specimens of patients with distant metastatic development and identifying potential targetable biomarkers or mutations.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Su CC S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Khelfa Y, Mansour M, Abdel-Aziz Y, Raufi A, Denning K, Lebowicz Y. Relapsed Acinic Cell Carcinoma of the Parotid Gland With Diffuse Distant Metastasis: Case Report With Literature Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2016;4:2324709616674742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim SA, Mathog RH. Acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland: a 15-year review limited to a single surgeon at a single institution. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84:597-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Das R, Nath G, Bohara S, Bhattacharya AB, Gupta V. Two Unusual Cases of Acinic Cell Carcinoma: Role of Cytology with Histological Corelation. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ED21-ED22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin WN, Huang HC, Wu CC, Liao CT, Chen IH, Kan CJ, Huang SF. Analysis of acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland - 15 years experience. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:1406-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bury D, Dafalla M, Ahmed S, Hellquist H. High grade transformation of salivary gland acinic cell carcinoma with emphasis on histological diagnosis and clinical implications. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212:1059-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xiao CC, Zhan KY, White-Gilbertson SJ, Day TA. Predictors of Nodal Metastasis in Parotid Malignancies: A National Cancer Data Base Study of 22,653 Patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:121-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Magliulo G, Iannella G, Alessi S, Veccia N, Ciniglio Appiani M. Acinic cell carcinoma and petrous bone metastasis. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:e18-e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Edge SB, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, Byrd D. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2010. |

| 9. | Ali S, Bryant R, Palmer FL, DiLorenzo M, Shah JP, Patel SG, Ganly I. Distant Metastases in Patients with Carcinoma of the Major Salivary Glands. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4014-4019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bradley PJ. Distant metastases from salivary glands cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Binesh F, Akhavan A, Masumi O, Mirvakili A, Behniafard N. Clinicopathological review and survival characteristics of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;67:62-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mariano FV, da Silva SD, Chulan TC, de Almeida OP, Kowalski LP. Clinicopathological factors are predictors of distant metastasis from major salivary gland carcinomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:504-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van der Wal JE, Becking AG, Snow GB, van der Waal I. Distant metastases of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands and the value of diagnostic examinations during follow-up. Head Neck. 2002;24:779-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Otsuka K, Imanishi Y, Tada Y, Kawakita D, Kano S, Tsukahara K, Shimizu A, Ozawa H, Okami K, Sakai A, Sato Y, Ueki Y, Sato Y, Hanazawa T, Chazono H, Ogawa K, Nagao T. Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Factors for Salivary Duct Carcinoma: A Multi-Institutional Analysis of 141 Patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2038-2045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Weiland LH. Acinic cell carcinoma. Clinicopathologic review. Cancer. 1991;67:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vander Poorten V, Triantafyllou A, Thompson LD, Bishop J, Hauben E, Hunt J, Skalova A, Stenman G, Takes RP, Gnepp DR, Hellquist H, Wenig B, Bell D, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Salivary acinic cell carcinoma: reappraisal and update. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3511-3531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Robinson RA, Pinkston JA, Menck HR. National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck: acinic cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 1999;21:297-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patel NR, Sanghvi S, Khan MN, Husain Q, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Demographic trends and disease-specific survival in salivary acinic cell carcinoma: an analysis of 1129 cases. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu Y, Su M, Yang Y, Zhao B, Qin L, Han Z. Prognostic Factors Associated With Decreased Survival in Patients With Acinic Cell Carcinoma of the Parotid Gland. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:416-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cha W, Kim MS, Ahn JC, Cho SW, Sunwoo W, Song CM, Kwon TK, Sung MW, Kim KH. Clinical analysis of acinic cell carcinoma in parotid gland. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;4:188-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Thompson LD, Aslam MN, Stall JN, Udager AM, Chiosea S, McHugh JB. Clinicopathologic and Immunophenotypic Characterization of 25 Cases of Acinic Cell Carcinoma with High-Grade Transformation. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:152-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Neskey DM, Klein JD, Hicks S, Garden AS, Bell DM, El-Naggar AK, Kies MS, Weber RS, Kupferman ME. Prognostic factors associated with decreased survival in patients with acinic cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:1195-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |