Published online Aug 24, 2019. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v10.i8.293

Peer-review started: February 24, 2019

First decision: June 17, 2019

Revised: July 3, 2019

Accepted: July 30, 2019

Article in press: July 30, 2019

Published online: August 24, 2019

Processing time: 180 Days and 23.5 Hours

Wilms tumor is the most common renal malignancy in childhood. It occurs primarily between the ages of 2 and 5 years. The usual manifestations are abdominal mass, hypertension, and hematuria. The case presented here had an unusual presentation, with dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertension secondary to the Wilms tumor.

A 3-year-old boy presented with a 5-d history of irritability, poor appetite, and respiratory distress. His presenting clinical symptoms were dyspnea, tachycardia, hypertension, and a palpable abdominal mass at the left upper quadrant. His troponin T and pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels were elevated. Echocardiography demonstrated a dilated hypokinetic left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 29%, and a suspected left renal mass. Computed tomography scan revealed a left renal mass and multiple lung nodules. The definitive diagnosis of Wilms tumor was confirmed histologically. The patient was administered neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent radical nephrectomy. After surgery, radiotherapy was administered, and the adjuvant chemotherapy was continued. The blood pressure and left ventricular function normalized after the treatments.

Abdominal mass, dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertension can indicate Wilms tumor in pediatric patients. Chemotherapy and tumor removal achieve successful treatment.

Core tip: Wilms tumor is the most common renal malignancy in childhood. The usual manifestations are abdominal mass, hypertension, and hematuria. A 3-year-old male presented with an unusual clinical profile of dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertension secondary to Wilms tumor. Echocardiography demonstrated a dilated left ventricle with poor contractility and a suspected left renal mass. The definitive diagnosis of Wilms tumor was confirmed histologically. Wilms tumor should be included in the differential diagnosis of any pediatric patient with dilated cardiomyopathy and abdominal mass, regardless of the presence of hypertension. Treatment of chemotherapy and tumor removal resulted in an improvement of left ventricular function.

- Citation: Sethasathien S, Choed-Amphai C, Saengsin K, Sathitsamitphong L, Charoenkwan P, Tepmalai K, Silvilairat S. Wilms tumor with dilated cardiomyopathy: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2019; 10(8): 293-299

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v10/i8/293.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v10.i8.293

Wilms tumor, also known as nephroblastoma, is the most common renal malignancy in childhood and the second most common intraabdominal malignancy, accounting for 6% of all pediatric tumors. The age-adjusted incidence rate of Wilms tumor in Thailand is 2.7 per million[1]. Wilms tumor occurs primarily between the ages of 2 and 5 years[2], and the typical presentation is an asymptomatic abdominal mass. Other signs and symptoms are abdominal pain, hematuria, and hypertension; although, dilated cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure are additional yet unusual presentations in patients with Wilms tumor, with only five cases reported previously[3-6]. On the other hand, pheochromocytoma could also be suspected in a patient with acute myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertension[7-10]. Intracaval and intracardiac extension of the tumor thrombus is a cardiovascular complication occurring in 4%-10% of Wilms tumor[11-13]. This report describes a pediatric case of Wilms tumor with an unusual presentation of dilated cardiomyopathy with hypertension that was determined to be secondary to the tumor.

A 3-year-old boy presented with acute myocarditis and congestive heart failure.

The patient was hospitalized at a primary hospital, with a 5-d history of irritability, poor appetite, and respiratory distress. A chest radiograph revealed mild cardiomegaly and pulmonary infiltration. The patient was treated for bacterial pneumonia with a 3-d regimen of an oral antibiotic. He was then referred to a provincial hospital due to his symptoms not improving. His vital signs were as follows: heart rate of 144/min; respiratory rate of 65/min; blood pressure of 145/94 mmHg (right arm) and 144/102 mmHg (left arm), and of 169/90 mmHg (right leg) and 150/119 mmHg (left leg). He had dyspnea, tachycardia, hepatomegaly, and an oxygen saturation of 97%. Bilateral fine crepitations were audible over both lungs. Cardiac examination detected no murmur, regular rhythm, and normal first and second heart sounds, but also revealed an S3 gallop. His liver was palpated 6 cm below the right costal margin.

A firm, non-tender mass was detected at the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, with the lower border at 8 cm below the left costal margin, and was suspected to be an enlarged spleen. A chest radiograph showed mild cardiomegaly and diffuse pulmonary infiltration. Electrocardiography noted a condition of sinus tachycardia and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy. The two-dimensional and color Doppler echocardiography demonstrated presence of a hypokinetic LV wall with an ejection fraction of 29%, no mitral regurgitation, and normal coronary anatomy. The patient was diagnosed with acute myocarditis and treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, milrinone, furosemide, and spironolactone. He was referred to the Chiang Mai University Hospital (Chiang Mai, Thailand) because of the acute myocarditis, poor LV contractility, and hypertension.

The patient was reportedly healthy before the present illness.

The patient had hypertension and a mass at the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, with the lower border at 8 cm below the left costal margin and suspected to be splenomegaly.

On admission, the blood chemistry exam revealed normal renal function, elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase 119 U/L, normal: 0-40 U/L; alanine aminotransferase 139 U/L, normal: 0-41 U/L), slightly elevated troponin T (50 pg/mL, normal: ≤ 14 pg/mL), elevated CKMB (6.1 ng/mL, normal: < 4.8 ng/mL), and markedly elevated pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (21,736 pg/mL, normal: < 300 pg/mL). Urinary analysis showed microscopic hematuria. The patient also had substantially elevated serum chromogranin A (156.9 ng/mL, normal: 31-94 ng/mL), plasma renin activity (34.75 ng/mL/h, normal: 0.06-4.69 ng/mL/h), and plasma aldosterone (961 pg/mL, normal: 20-180 pg/mL). The urinary level of metanephrines was within normal range (56.15 μg/d, normal: 25-312 μg/d).

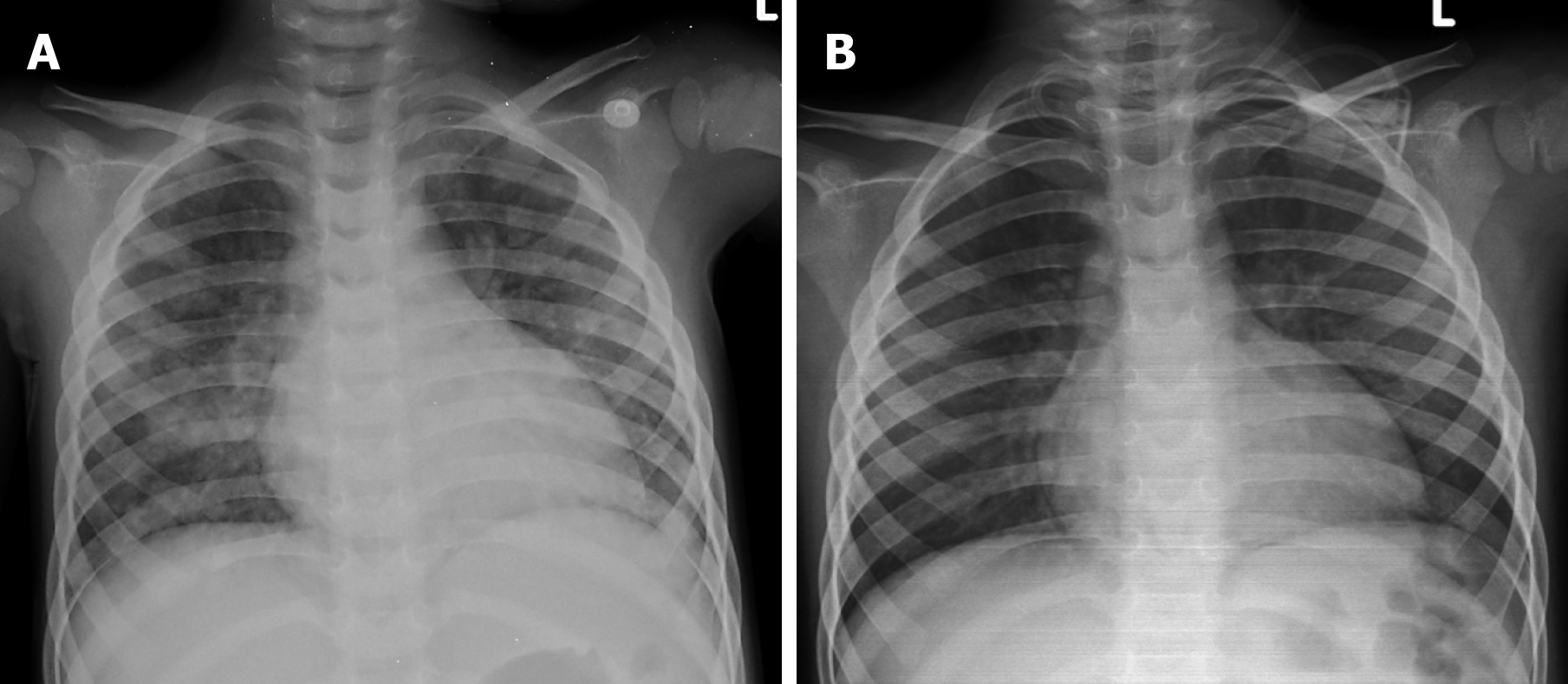

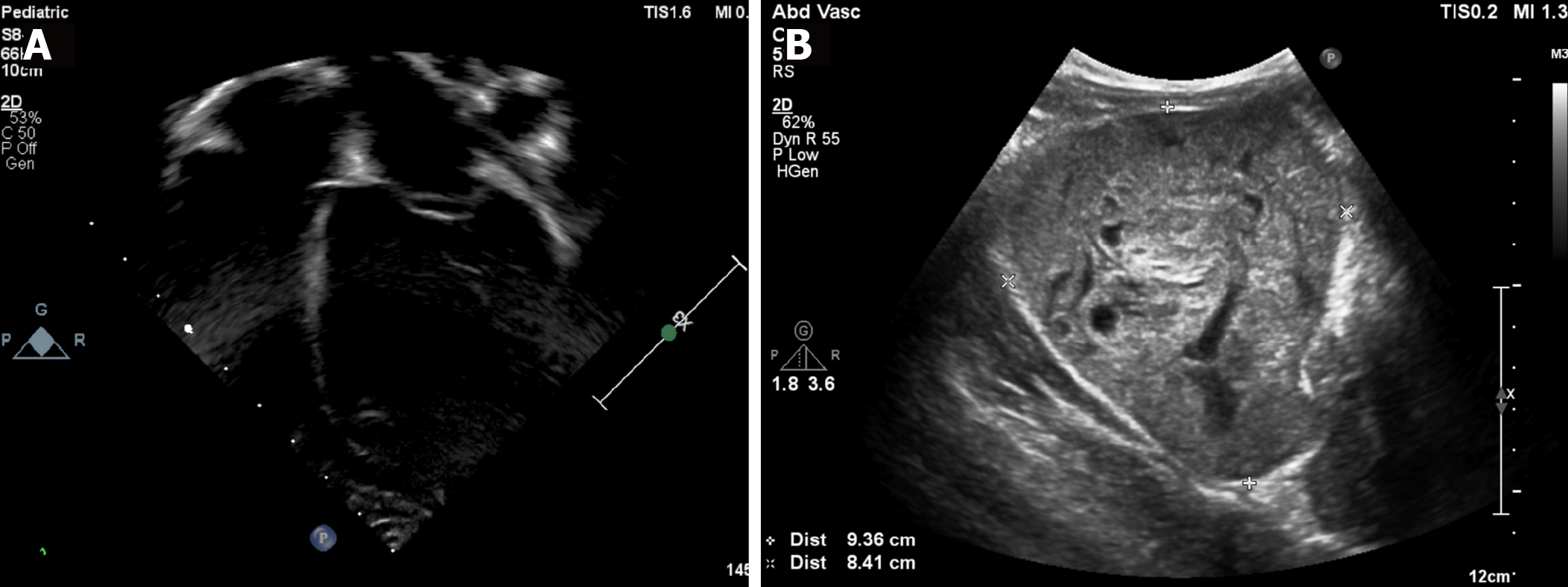

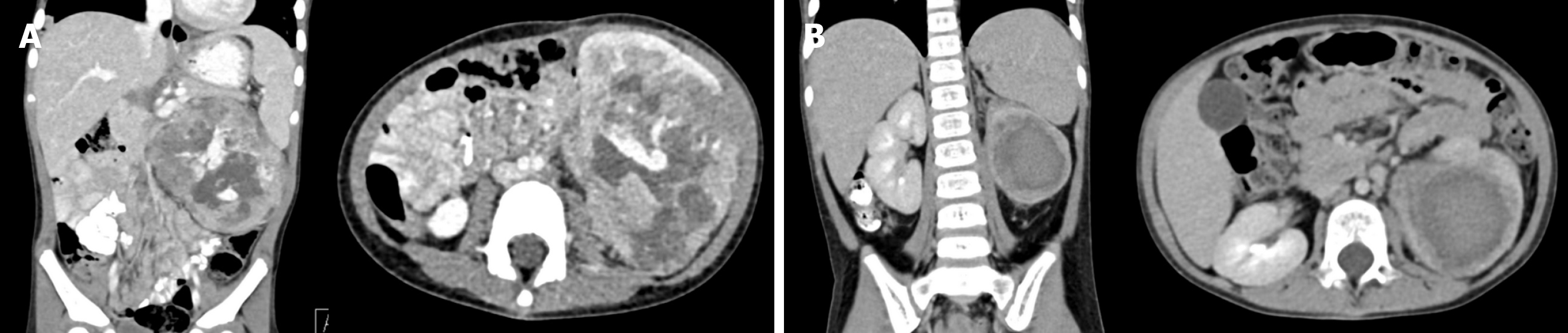

A chest radiograph revealed cardiomegaly with a cardiothoracic ratio of 60% and diffuse small pulmonary nodules (Figure 1A). Echocardiography was performed to determine the cause of the acute myocarditis and hypertension. A dilated left ventricle with poor contractility (LV ejection fraction of 30%) and an 8 cm × 9 cm left renal mass were demonstrated (Figure 2). Chest and abdominal computed tomography (commonly referred to as CT) scans delineated the existence of a large lobulated heterogeneously hypoenhancing 9.7 cm × 9.7 cm × 9.5 cm soft tissue mass occupying the left kidney, with intralesional necrotic and non-enhancing cystic portions (Figure 3A). In addition, a thrombus in the left renal vein, ascites, multiple pulmonary nodules, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy were noted. Wilms tumor with lung metastasis was suspected.

A core needle biopsy of the mass was performed to confirm the diagnosis. The tissue histology revealed the triphasic pattern of Wilms tumor and absence of anaplasia.

The patient received intravenous milrinone, furosemide, spironolactone, enalapril, amlodipine, and prazosin for treatment of the LV dysfunction with congestive heart failure and hypertension. Also, low molecular weight heparin was administered for treatment of his left renal vein thrombosis. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (using a regimen of etoposide and carboplatin) was initiated.

Chest and abdominal CT scans after the first course of chemotherapy revealed a decrease in size of the tumor mass and newly developed pulmonary embolism in the left descending artery supplying basal segments of the left lower lobe. However, the patient showed no sign of deterioration. The planned radical nephrectomy was postponed because of the patient’s very large tumor mass, ascites, and pulmonary embolism. After three courses of chemotherapy, the tumor mass decreased in size, measuring 5.7 cm × 5.1 cm × 5.8 cm in the axial and vertical diameters, respectively (Figure 3B). A chest radiograph revealed mild cardiomegaly with a cardiothoracic ratio of 55% and absence of pulmonary nodules (Figure 1B). A chest CT scan showed marked decrease in the size and number of pulmonary nodules.

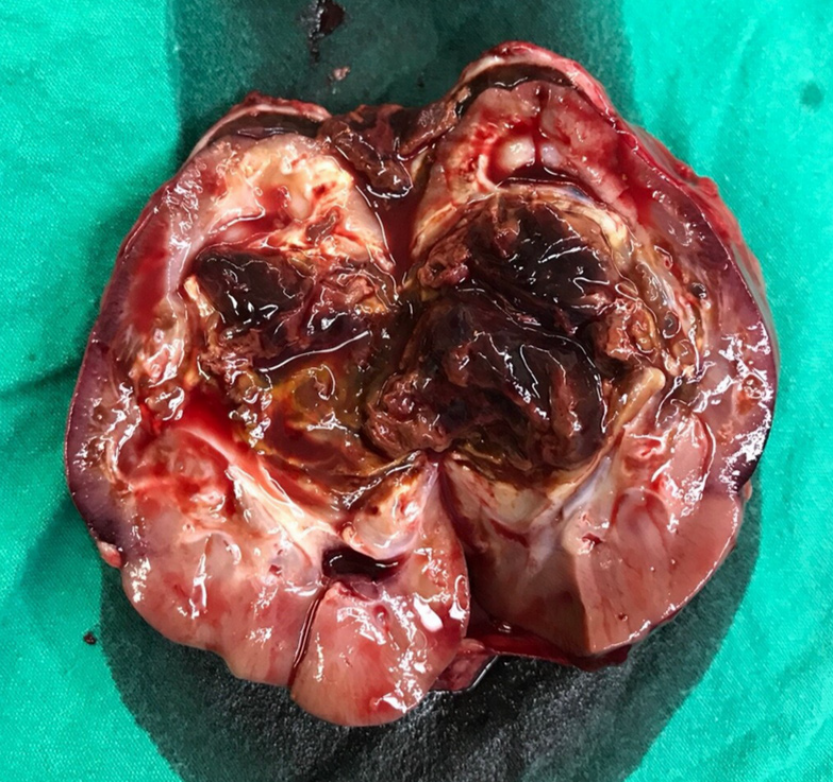

At 3 mo after the initiation of treatment, the patient had no clinical evidence of congestive heart failure. Echocardiography demonstrated improved LV contractility, with an ejection fraction of 50%. An adjuvant chemotherapy comprising dactinomycin, vincristine and doxorubicin was administered. The left radical nephrectomy was then performed at 4 mo after the diagnosis (Figure 4). The postoperative histopathological report confirmed Wilms tumor with triphasic pattern and absence of anaplasia. After surgery, the patient underwent radiation therapy to the whole lung and left flank, while the adjuvant chemotherapy was continued. His plasma renin decreased to a normal level (2.83 ng/mL/h); blood pressure normalized and echocardiography showed good LV contractility, with an ejection fraction of 58%.

This present case had an unusual presentation of dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertension secondary to Wilms tumor. Dilated cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure are rare presenting signs and symptoms of Wilms tumor, of which there have been only five reported cases previously[3-6]. All of the reported cases, along with our case presented herein, are summarized in Table 1. Hypertension accompanied by dilated cardiomyopathy was noted in three of the five previously reported patients with Wilms tumor. Also, three of the five previously reported cases showed hyperreninemia with hypertension and congestive heart failure. Trebo et al[5] reported two cases of Wilms tumor with dilated cardiomyopathy and absence of hyperreninemia. The authors postulated that vasoactive mediators other than renin being produced from the Wilms tumor as the cause of the dilated cardiomyopathy without hypertension or elevated renin. The removal of the Wilms tumor alleviated the deterioration of the cardiac function in both of those previous cases.

| Ref. | Age, sex | Primary tumor (size) | Stage | Presenting symptoms | Laboratory findings | Treatment and outcome |

| Stine et al[3], 1986 | 9 mo, male | Bilateral kidneys | V | Abdominal distension, CHF, HT | Hyperreninemia, increased aldosterone level | Chemotherapy, partial nephrectomy |

| Resolved CHF/HT after 3 mo | ||||||

| (11 cm× 11 cm × 9 cm, 13 cm × 13 cm × 9 cm) | ||||||

| Agarwala et al[4], 1997 | 2 yr, female | Right kidney | II | CHF, pulmonary edema, DCM, HT | Hyperreninemia | Right nephrectomy, chemotherapy |

| (10 cm × 15 cm × 8 cm) | Resolved CHF/HT after 1 yr | |||||

| Trebo et al[5], 2003 | 2.5 yr, female | Right kidney | IV | DCM, no HT | Normal renin level | Right nephrectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy |

| Resolved CHF/HT after 3 yr | ||||||

| 8 mo, female | Right kidney | I | DCM, HT | Normal renin level | Right nephrectomy | |

| Resolved CHF/HT after 2 mo | ||||||

| Chalavon et al[6], 2017 | 7 mo, female | Right kidney | I | CHF, pulmonary edema, DCM, no HT | Hyperreninemia, increased angiotensin II level | Right nephrectomy, chemotherapy |

| (8.5 cm × 10 cm × 8 cm) | Resolved CHF/HT after 10 mo | |||||

| Present case, 2018 | 3 yr, male | Left kidney | IV | CHF, DCM, HT | Hyperreninemia, increased aldosterone level | Left nephrectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy |

| (9.7 cm × 9.7 cm × 9.5 cm) | Resolved CHF/HT after 3 mo |

Systemic hypertension secondary to high serum renin is common. Two hypotheses have been proposed for the etiology of hyperreninemia, including a mechanical compression of the renal artery leading to renal ischemia and a production of renin by the Wilms tumor[14-16]. In our case, the tumor mass displaced the left renal vessels, with a gross invasion causing a filling defect of thrombus in the left renal vein that was likely the cause of the elevated serum renin. The hyperreninemia resulted in increased angiotensin II, aldosterone and vasoconstriction, as well as fluid retention, all leading to hypertension and dilated cardiomyopathy. In addition, several studies have demonstrated that angiotensin II plays an important role in cardiac remodeling and dysfunction, regardless of the hemodynamic abnormality[17-19]. After treatment with chemotherapy, the size of our patient’s tumor mass decreased and the LV function gradually improved. In addition, his LV contractility returned to normal after the left radical nephrectomy.

Wilms tumor is characterized by a tendency to invade blood vessels. Extension of a tumor thrombus along the renal vein into the inferior vena cava and right atrium occurs in 4%-10% of all patients with Wilms tumor[11-13]. In the present case, the thrombus was noted in the left renal vein and a pulmonary embolism developed in the left descending artery supplying basal segments of the left lower lobe. Furthermore, Wilms tumor can cause hematogenous metastasis to the lymph nodes, lung, liver, bone, or brain. The case presented herein represented Wilms tumor stage 4 with multiple pulmonary metastases and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

An abdominal mass with or without hematuria and hypertension is a common presentation, whereas dilated cardiomyopathy is an uncommon presenting symptom in patients with Wilms tumor. Wilms tumor should be included in the differential diagnosis of any patient, particularly pediatric, with dilated cardiomyopathy and an abdominal mass, regardless of the presence of hypertension. In a patient with acute myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy with hypertension in which other causes of hypertension are not identified, an abdominal ultrasound should be performed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Thailand

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kupeli S, Yamagata M S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Wiangnon S, Veerakul G, Nuchprayoon I, Seksarn P, Hongeng S, Krutvecho T, Sripaiboonkij N. Childhood cancer incidence and survival 2003-2005, Thailand: study from the Thai Pediatric Oncology Group. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:2215-2220. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Malkan AD, Loh A, Bahrami A, Navid F, Coleman J, Green DM, Davidoff AM, Sandoval JA. An approach to renal masses in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;135:142-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stine KC, Goertz KK, Poisner AM, Lowman JT. Congestive heart failure, hypertension, and hyperreninemia in bilateral Wilms' tumor: successful medical management. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1986;14:63-66. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Agarwala B, Mehrotra N, Waldman JD. Congestive heart failure caused by Wilms' tumor. Pediatr Cardiol. 1997;18:43-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Trebo MM, Mann G, Dworzak M, Zoubek A, Gadner H. Wilms tumor and cardiomyopathy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41:574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chalavon E, Lampin ME, Lervat C, Leroy X, Bonnevalle M, Recher M, Sudour-Bonnange H. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Caused by Wilms Tumor. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:41-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de Miguel V, Arias A, Paissan A, de Arenaza DP, Pietrani M, Jurado A, Jaén A, Fainstein Day P. Catecholamine-induced myocarditis in pheochromocytoma. Circulation. 2014;129:1348-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ferreira VM, Marcelino M, Piechnik SK, Marini C, Karamitsos TD, Ntusi NAB, Francis JM, Robson MD, Arnold JR, Mihai R, Thomas JDJ, Herincs M, Hassan-Smith ZK, Greiser A, Arlt W, Korbonits M, Karavitaki N, Grossman AB, Wass JAH, Neubauer S. Pheochromocytoma Is Characterized by Catecholamine-Mediated Myocarditis, Focal and Diffuse Myocardial Fibrosis, and Myocardial Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2364-2374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang R, Gupta D, Albert SG. Pheochromocytoma as a reversible cause of cardiomyopathy: Analysis and review of the literature. Int J Cardiol. 2017;249:319-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khattak S, Sim I, Dancy L, Whitelaw B, Sado D. Phaeochromocytoma found on cardiovascular magnetic resonance in a patient presenting with acute myocarditis: an unusual association. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hadley GP, Sheik-Gafoor MH, Buckels NJ. The management of nephroblastoma with cavo-atrial disease at presentation: experience from a developing country. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:1169-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abdullah Y, Karpelowsky J, Davidson A, Thomas J, Brooks A, Hewitson J, Numanoglu A, Cox S, Millar AJ. Management of nine cases of Wilms' tumour with intracardiac extension - a single centre experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:394-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cox SG, Davidson A, Thomas J, Brooks A, Hewitson J, Numanoglu A, Millar AJW. Surgical management and outcomes of 12 cases of Wilms tumour with intracardiac extension from a single centre. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34:227-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mitchell JD, Baxter TJ, Blair-West JR, McCredie DA. Renin levels in nephroblastoma (Wilms' tumour). Report of a renin secreting tumour. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:376-384. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Spahr J, Demers LM, Shochat SJ. Renin producing Wilms' tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:32-34. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Maas MH, Cransberg K, van Grotel M, Pieters R, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Renin-induced hypertension in Wilms tumor patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:500-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Serneri GG, Boddi M, Cecioni I, Vanni S, Coppo M, Papa ML, Bandinelli B, Bertolozzi I, Polidori G, Toscano T, Maccherini M, Modesti PA. Cardiac angiotensin II formation in the clinical course of heart failure and its relationship with left ventricular function. Circ Res. 2001;88:961-968. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Huggins CE, Domenighetti AA, Pedrazzini T, Pepe S, Delbridge LM. Elevated intracardiac angiotensin II leads to cardiac hypertrophy and mechanical dysfunction in normotensive mice. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2003;4:186-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peng H, Yang XP, Carretero OA, Nakagawa P, D'Ambrosio M, Leung P, Xu J, Peterson EL, González GE, Harding P, Rhaleb NE. Angiotensin II-induced dilated cardiomyopathy in Balb/c but not C57BL/6J mice. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:756-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |