Published online May 24, 2019. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v10.i5.213

Peer-review started: January 25, 2019

First decision: January 29, 2019

Revised: February 15, 2019

Accepted: March 16, 2019

Article in press: March 16, 2019

Published online: May 24, 2019

Processing time: 119 Days and 7.6 Hours

Clear cell sarcoma is an aggressive rare malignant neoplasm with morphologic and immunohistochemical similarities to malignant melanoma. Both disease entities display melanin pigment and melanocytic markers, making differentiation between the two difficult. Although clear cell sarcoma cases in the literature have mainly involved deep soft tissues of the extremities, trunk or limb girdles, we report here two cases of primary clear cell sarcoma in unusual sites and describe their clinicopathologic findings.

The first case involves a 37-year-old female, who presented with jaw pain and a submandibular mass. The second case involves a 33-year-old male, who presented with back pain and a thoracic spine tumor. Both cases showed tumors with diffuse infiltration of neoplastic cells that were positive for melanocytic markers, and in both cases this finding led to an initial diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. However, further analysis by fluorescence in situ hybridization (commonly known as FISH) showed a rearrangement of the EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) gene on chromosome 22q12 in both patients, confirming the diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma.

Distinction between clear cell sarcoma and malignant melanoma can be made by FISH, particularly in cases of unusual tumor sites.

Core tip: The diagnosis and management of clear cell sarcoma can be a clinical dilemma. Recognition of the clinicopathologic pattern and differentiating it from malignant melanoma can prevent misdiagnosis. This case report not only represents the first reported occurrence of clear cell sarcoma in the submandibular gland in the literature but also identifies another unusual location of involvement, the thoracic spine. It is important to promptly recognize this disease entity because early treatment is necessary to prevent fatal consequences.

- Citation: Obiorah IE, Ozdemirli M. Clear cell sarcoma in unusual sites mimicking metastatic melanoma. World J Clin Oncol 2019; 10(5): 213-221

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v10/i5/213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v10.i5.213

Clear cell sarcoma (also known as melanoma of the soft parts) was initially described by Dr. Franz Enzinger[1] in 1965, when he identified it as a sarcoma arising from the tendons and aponeurosis of extremities with a distinctive clinical and morphological pattern. Today, we understand clear cell sarcoma to be an aggressive tumor that accounts for only 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas, affecting mainly adolescents and young adults, and associated with local recurrences and late metastasis. Although both malignant melanoma and clear cell sarcoma display similar melanocytic markers, the two disorders are genetically distinct. Cases of malignant melanoma may contain BRAF mutations[2], whereas clear cell sarcoma lacks this mutation[3] and characteristically exhibits the reciprocal translocation t(12;22)(q13;q12) resulting in a rearrangement of the EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) gene[4,5].

Clear cell sarcoma of the head and neck are uncommon[6,7]. Tumors arising from the salivary glands are extremely rare but have been described previously in the parotid gland[8-10]. Similarly, clear cell sarcoma of the thoracic spine or paraspinal soft tissues is very rare and very few cases have been reported[11]. To our knowledge, no cases of clear cell sarcoma of the submandibular gland have been published in the literature. We report herein the clinicopathologic findings of two cases of primary clear cell sarcoma arising in the submandibular gland and the thoracic spine, respectively, and highlight the challenges in their diagnosis as well as the importance of molecular genetics in differentiating this tumor type from malignant melanoma.

Chief complaints: A 37-year-old female presented to our hospital with complaint of left jaw pain and swelling.

History of present illness: The patient reported the symptoms having been present for 6 mo.

History of past illness: The patient’s past medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination: A left neck mass was felt on palpation.

Laboratory testing: Histological assessment of a fine-needle aspirate of the mass showed epithelioid-looking neoplastic cells with enlarged eccentric nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Based on these cytomorphologic features, the differential diagnosis of a high-grade carcinoma, hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma was proposed.

Surgical investigation and resection: The patient was referred to the surgical team and based on the preliminary diagnosis, it was decided that the mass should be resected along with regional lymph node dissection. The patient underwent a left neck dissection and excision of the left neck mass. Histopathologic examination revealed nests of poorly differentiated malignant cells with pleomorphic vesicular nuclei, mitotic figures and clear cytoplasm (Figure 1). The tumor cells had invaded the adjacent soft tissue but no bone involvement was present. The cervical lymph node dissection yielded two metastatic adenopathies among the eighteen dissected lymph nodes. Immunohistochemical staining showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for Human Melanoma Black-45 (commonly known as HMB-45; a melanocytic tumor marker) (Figure 2A), S-100 (Figure 2B) and vimentin, but were negative for cytokeratin (Figure 2C), calponin, smooth muscle actin, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and glial fibrillary acidic protein. Some of the tumor cells contained melanin pigment, which reacted positively in Masson Fontana staining (Figure 2D). These results supported the initial diagnosis of malignant melanoma and excluded the diagnosis of a clear cell carcinoma due to negativity for cytokeratin.

Chief complaints: A 33-year-old male presented to our institution with complaint of mid back pain radiating to the flanks, and leg weakness and numbness, with gait abnormalities.

History of present illness: The patient reported the symptoms having been present for 6 mo.

History of past illness: The patient had no past medical history.

Physical examination: On physical examination, the patient showed a wide-based, unsteady gait, with weakness and decreased sensation and reflexes in both lower limbs.

Imaging examination: An MRI scan showed a mass enhancement in the T6 and T7 region of the spine (Figure 3A), raising suspicion of a paraspinal mass causing compression on the spinal cord.

Surgical investigation and resection:The patient was referred to the neurosurgical team, who decided to completely resect the tumor for pathological assessment to determine the diagnosis. A T6-7 laminectomy was performed, with complete resection of the tumor. Intraoperatively, the tumor was found to grossly involve the thoracic spine, with predominant involvement of the paraspinal soft tissues. Pathological examination of the resected neoplasm showed fascicles and nests of spindle cells (Figure 3B) with epithelioid features, eosinophilic cytoplasm, occasional mitosis, and pigment in some of the cells (Figure 3C). The tumor cells were positive for HMB-45 (Figure 3D), S-100 and melanoma antigen (Melan-A), but were negative for cytokeratin, desmin, smooth muscle actin, and glial fibrillary acidic protein. The pigment in the tumor cells was confirmed to contain melanin by reacting positivity with the Masson Fontana stain. These results supported the initial diagnosis of malignant melanoma.

The case was sent out to two different institutions, with all subsequent experts agreeing with the diagnosis of melanoma. An extensive dermatological, ophthalmological and radiological workup of the patient was performed to rule out a primary site. Skin and mucosal surfaces did not reveal any suspicious lesions. A whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck region did not show any ocular involvement or masses in any other sites.

This case was handled fully within our institution by the clinical staffs described.

At this time, the diagnosis was melanoma.

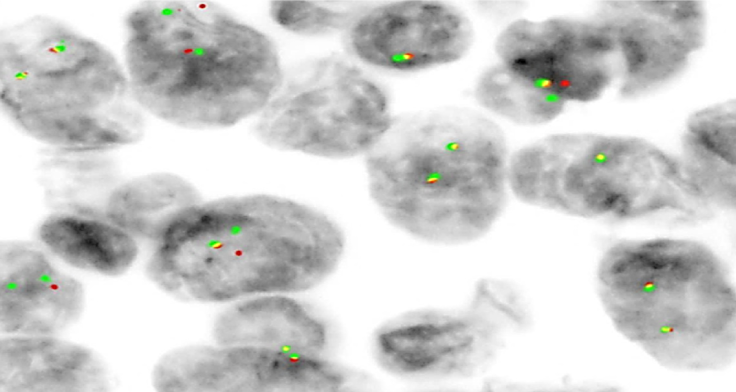

Because our past experience had taught us that clear cell sarcoma can readily mimic malignant melanoma, a FISH study was ordered. An EWSR1 gene rearrangement on chromosome 22q12 was found (Figure 4). This confirmed the diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma of the thoracic spine involving the paraspinal soft tissues.

The patient was started on adjuvant therapy with interferon alpha-2 (18 MIU three times a week for 8 wk). Two months later, the patient developed an enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node. She was started on localized radiation (4 fractions of 8 Gy weekly) to the supraclavicular node, in addition to the interferon 2-alpha she was currently on. While on treatment, the tumor progressed to involve the left pterygoid region, extending towards the inferior aspect of the left masseter muscle and the temporalis muscle. The patient underwent an extensive resection of the tumor with partial removal of her left jaw, followed by additional radiation therapy.

Four months later, the patient presented with metastatic disease to the lungs, spine and left neck soft tissue, and died shortly afterward. On further review at 8 years later, we sent the resected tumor specimen for retrospective florescence in situ hybridization (FISH). A rearrangement of the EWSR1 gene on chromosome 22q12 was found, confirming the diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma.

Following surgery, a repeat MRI showed no evidence of residual tumor. Apart from lower back pain which was managed with pain medications, the post-operative course was uncomplicated. The patient was able to slowly ambulate with mild muscle weakness. The patient was discharged and referred to physical therapy for rehabilitation. Two months post-surgery, the patient was stable, ambulatory and undergoing physical therapy with no recurrence of the thoracic tumor on MRI. Adjuvant standard fractionation radiotherapy (2 Gy a day) was given for 5 d. At 6 mo post-surgery follow-up visit, MRI showed post-surgical changes in the mid thoracic region with no evidence of a recurrent tumor. Currently the patient has intermittent lower back pain due to poor posture and has no neurological deficits. His muscle strength has greatly improved due to compliance with physical therapy. The patient will be monitored closely for recurrence with MRI every 6 mo.

Clear cell sarcoma typically involves tendons and aponeurosis[1,12] of adolescents and young adults of both sexes. The tumor usually presents as a small insidiously growing mass, but it can suddenly become aggressive and rapidly metastasize, as was observed in our patient (Case 1). Following Enzinger’s initial description of the clear cell sarcoma, Chung and Enzinger[12] demonstrated melanin in 72% of tumors with clear cell sarcoma, supporting their origin from migrated neural crest cells. As such, they coined the name “malignant melanoma of soft parts”, which seems preferable over the more descriptive term of clear cell sarcoma. In addition, clear cell sarcoma has been shown to be positive for antigens associated with the synthesis of melanin, such as HMB-45, S-100 protein and Melan-A[13,14]. Moreover, electron microscopy has demonstrated melanosomes in clear cell sarcoma, similar to malignant melanoma. For these reasons, clear cell sarcoma is thought to be a subtype of malignant melanoma, albeit genetically distinct. Typically, cases of clear cell sarcoma have a reciprocal translocation [t(12;22)(q13;q12)] resulting in an EWSR1-activating transcription factor (ATF) gene fusion[4,5,15]. The second major differential diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma will include a clear cell carcinoma, such as the hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma; however, carcinomas are readily diagnosed by immunohistochemistry, which should show a positive cytokeratin stain.

Herein, we present first a case of clear cell sarcoma occurring in the submandibular gland (Table 1) that closely resembled a malignant melanoma on histological analysis. There was a concurrence of the initial malignant melanoma diagnosis when two outside institutions were consulted. The initial misdiagnosis was due to the morphologic and immunohistochemical similarities between clear cell sarcoma and malignant melanoma and lack of awareness of the t(12;22)(q13;q12) translocation, which was only recently described. Immunohistochemistry excluded a clear cell carcinoma, smooth muscle tumors, neuroendocrine neoplasms, or primary brain tumors. Additional supportive findings for the case to be a primary clear cell sarcoma are that the lesion was solitary and metastasis was present only in the cervical lymph nodes draining from the submandibular mass. These findings illustrate the typical spread of clear cell sarcoma from a primary site to regional lymph nodes[12,14]. Secondly, there was absence of malignancy elsewhere in the body, thereby supporting our diagnosis of a primary clear cell sarcoma arising from the submandibular gland. To our knowledge, this is the first report to describe a case of primary clear cell sarcoma of the submandibular gland. In general, clear cell sarcoma of the salivary gland is extremely rare. At the time of this report only three cases involving the salivary gland have been published, all of which had arisen in the parotid gland and were treated surgically[8,10]. Only one of those cases[10] recurred after surgery, and the patient was alive with no evidence of the disease after radical neck surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

| Dates | Relevant past medical history and intervention | ||

| Summaries from initial and follow-up visits | Diagnostic testing | Interventions | |

| July 2009 | Patient presented with a 6-mo history of left jaw pain and mass | Cytological examination of fine-needle aspirate of the mass | Surgical resection of the neck mass |

| July 2009 | Post-surgery follow-up | A whole-body PET/CT scan and MRI of the head and neck region | Interferon alpha-2 (18 MIU three times a week for 8 wk) |

| September 2009 | On routine follow-up, an enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node was identified | PET/CT scan | Radiotherapy to the supraclavicular node in addition to the interferon alpha-2 |

| October 2009 | Metastatic disease to the left pterygoid region, masseter muscle and the temporalis muscle | PET/CT scan and MRI | Complete resection of involved areas with adjuvant weekly radiotherapy |

| February 2010 | Metastatic disease to the lungs, spine and left neck soft tissue | PET/CT scan and MRI | Expired within a wk |

Our second case presented with a T6-7 paraspinal mass, which was given an initial diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Based on our previous experience we performed FISH testing, which demonstrated the EWRS1 rearrangement and confirmed the diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma. Clear cell sarcoma of the thoracic spine or paraspinal soft tissues is extremely rare. Gao et al[11] found only four cases reported in the literature. All of these presented with back pain. Two of these patients were treated successfully by complete resection of the tumor with clear margins, while another patient was treated with surgery and chemotherapy, and experienced local recurrence[16]. There was no follow-up information for the fourth case[17]. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for clear cell sarcoma, with chemotherapy having little effect[18,19]. About a third of patients with clear cell sarcoma receive radiotherapy mostly in conjunction with surgery. Although radiation therapy has been shown to reduce the size of these tumors, clear beneficial effects of radiotherapy alone is difficult to assess since most cases are given either pre- or post-operatively[18,19]. Chemotherapy is predominantly used in patients with metastatic disease, however, prognosis is very poor, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of only 15%[18,20]. Targeted therapies, such as receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors, have shown benefit in some patients with this high-grade sarcoma, but most of these treatment strategies have so far only been applied in clinical trial settings[21]. Although surgery remains the treatment of choice for clear cell sarcoma, these tumors tend to recur. The reported rates of local recurrence of clear cell sarcoma following surgery reach up to 84%, with late metastases up to 63% and metastases at presentation up to 30%[5,14]. A recent review by Gonzaga et al[22] showed that the approximate 5- and 10-year overall survival for 489 patients with clear cell sarcoma was 50% and 38%, respectively. The estimated 5-year survival for Stages I–IV was 75%, 65%, 35% and 15%, respectively. In addition, the mean survival for Stage I was 94.9 mo, Stage II was 94.7 mo, Stage III was a median of 24.9 mo, and Stage IV was a median of 8.9 mo. Our first patient (case1) underwent complete excision of the tumor but the patient had metastasis to the regional lymph nodes. It is possible that the metastatic lymph nodes were not completely excised which led to recurrence. Although the diagnosis of the patient was not evident at the time, the patient received the correct modalities of therapy published in the literature which included surgery and radiotherapy. However, the aggressiveness and rapid progression of the disease led to fatal consequences. The second patient had complete surgical resection with adjuvant radiation treatment. The patient is currently stable with an estimated 5-year survival of about 70% based on prior studies[22]. We recently reported a case of clear cell sarcoma of the dermis that was completely excised and the patient is currently disease free two years post resection[23]. Based on our limited experience and published literature, it appears that early detection and tumor resection is the key to good clinical outcome[22,23]. Due to the rarity of the entity in the submandibular gland and thoracic spine, it is not possible at present to predict the outcome of treatment in the afflicted patients.

Clear cell sarcoma of the submandibular gland and thoracic spine or paraspinal soft tissues are rare disease entities. The presentation, histology, and tumor prognosis appear to be similar to the clear cell sarcoma arising elsewhere. FISH studies should be done on all tumors that demonstrate melanocytic markers without a cutaneous or mucosal malignant melanoma, to prevent a misdiagnosis of malignant melanoma. Although malignant melanoma and clear cell sarcoma are both aggressive tumors, it is important to differentiate between the two because of their different underlying pathophysiological pathways and therapeutic implications.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ierardi E, Tang Y S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Enzinger FM. Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. an analysis of 21 cases. Cancer. 1965;18:1163-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mesbah Ardakani N, Leslie C, Grieu-Iacopetta F, Lam WS, Budgeon C, Millward M, Amanuel B. Clinical and therapeutic implications of BRAF mutation heterogeneity in metastatic melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017;30:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, Mandahl N. Absence of mutations of the BRAF gene in malignant melanoma of soft parts (clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses). Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;156:74-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Langezaal SM, Graadt van Roggen JF, Cleton-Jansen AM, Baelde JJ, Hogendoorn PC. Malignant melanoma is genetically distinct from clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeurosis (malignant melanoma of soft parts). Br J Cancer. 2001;84:535-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mavrogenis A, Bianchi G, Stavropoulos N, Papagelopoulos P, Ruggieri P. Clinicopathological features, diagnosis and treatment of clear cell sarcoma/melanoma of soft parts. Hippokratia. 2013;17:298-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Feasel PC, Cheah AL, Fritchie K, Winn B, Piliang M, Billings SD. Primary clear cell sarcoma of the head and neck: a case series with review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:838-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hicks MJ, Saldivar VA, Chintagumpala MM, Horowitz ME, Cooley LD, Barrish JP, Hawkins EP, Langston C. Malignant melanoma of soft parts involving the head and neck region: review of literature and case report. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:395-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang L, Jia Z, Mao F, Shi Y, Bu RF, Zhang B. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a somatic missense mutation of NBN in clear cell sarcoma of the salivary gland. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3349-3356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Poignonec S, Lamas G, Homsi T, Auriol M, De Saint Maur PP, Castro DJ, Aidan P, Le Charpentier Y, Szalay M, Soudant J. Clear cell sarcoma of the pre-parotid region: an initial case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1994;48:369-373. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Manoel EM, Reiser R, Brodskyn F, Franco M, Abrahão M, Cervantes O. Clear cell sarcoma of the parotid region. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;78:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gao X, Zhao C, Wang J, Cai X, Chen G, Liu W, Zou W, He J, Xiao J, Liu T. Surgical management and outcomes of spinal clear cell sarcoma: A retrospective study of five cases and literature review. J Bone Oncol. 2017;6:27-31. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Malignant melanoma of soft parts. A reassessment of clear cell sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:405-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dim DC, Cooley LD, Miranda RN. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:152-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hisaoka M, Ishida T, Kuo TT, Matsuyama A, Imamura T, Nishida K, Kuroda H, Inayama Y, Oshiro H, Kobayashi H, Nakajima T, Fukuda T, Ae K, Hashimoto H. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 33 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:452-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang L, Chen Y, Cui T, Knösel T, Zhang Q, Geier C, Katenkamp D, Petersen I. Identification of biomarkers to distinguish clear cell sarcoma from malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1463-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gollard R, Hussong J, Bledsoe J, Rosen L, Anson J. Clear cell sarcoma originating in a paraspinous tendon: case report and literature review. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:1593-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parker JB, Marcus PB, Martin JH. Spinal melanotic clear-cell sarcoma: a light and electron microscopic study. Cancer. 1980;46:718-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kawai A, Hosono A, Nakayama R, Matsumine A, Matsumoto S, Ueda T, Tsuchiya H, Beppu Y, Morioka H, Yabe H; Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a study of 75 patients. Cancer. 2007;109:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ferrari A, Casanova M, Bisogno G, Mattke A, Meazza C, Gandola L, Sotti G, Cecchetto G, Harms D, Koscielniak E, Treuner J, Carli M. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses in pediatric patients: a report from the Italian and German Soft Tissue Sarcoma Cooperative Group. Cancer. 2002;94:3269-3276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Yamamoto N, Mori Y, Asada N. Caffeine-potentiated chemotherapy and conservative surgery for high-grade soft-tissue sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3651-3656. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cornillie J, van Cann T, Wozniak A, Hompes D, Schöffski P. Biology and management of clear cell sarcoma: state of the art and future perspectives. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16:839-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gonzaga MI, Grant L, Curtin C, Gootee J, Silberstein P, Voth E. The epidemiology and survivorship of clear cell sarcoma: a National Cancer Database (NCDB) review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144:1711-1716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Obiorah IE, Brenholz P, Özdemirli M. Primary Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Dermis Mimicking Malignant Melanoma. Balkan Med J. 2018;35:203-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |