Published online Oct 24, 2019. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v10.i10.350

Peer-review started: February 27, 2019

First decision: April 11, 2019

Revised: July 22, 2019

Accepted: September 5, 2019

Article in press: September 5, 2019

Published online: October 24, 2019

Processing time: 240 Days and 5.5 Hours

Dual checkpoint inhibition improves response rates in treatment naïve patients with metastatic melanoma compared to monotherapy. However, it confers a higher rate of toxicity, including immune-related colitis. Steroids may not resolve symptoms in all cases. The use of vedolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against α4β7 integrin has proven effective in cases refractory to standard treatment.

We report the case of a 27-year-old female with Stage IVd metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab. She developed severe colitis refractory to methylprednisolone, infliximab and mycophenolate mofetil but responded to vedolizumab.

This case report supports vedolizumab use in severe immune related colitis refractory to standard immunosuppression.

Core tip: Dual checkpoint inhibition improves response rates in treatment naïve patients with metastatic melanoma compared to monotherapy. However, it confers a higher rate of toxicity, including immune-related colitis. The use of vedolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against α4β7 integrin has proven effective in cases refractory to standard treatment. This is a case report of a 27-year-old female with Stage IVd metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab. She developed severe colitis refractory to methylprednisolone, infliximab and mycophenolate mofetil but responded to vedolizumab. This supports its use in severe immune related colitis refractory to standard immunosuppression.

- Citation: Randhawa M, Gaughran G, Archer C, Pavli P, Morey A, Ali S, Yip D. Vedolizumab in combined immune checkpoint therapy-induced infliximab-refractory colitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2019; 10(10): 350-357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v10/i10/350.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v10.i10.350

Combined blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) is the standard of care in selected patients with metastatic melanoma given the improved response rates and overall survival compared with PD-1 inhibitors alone[1]. The use of combined immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPI’s), ipilimumab and nivolumab however also confers a higher rate of toxicity including gastrointestinal immune related adverse events (irAE) which tend to occur earlier when compared to monotherapy[1,2]. Severe irAE’s are more common with CTLA-4 inhibitors than with PD-1 blockade, with rates of diarrhea and colitis in melanoma patients on ipilimumab being as high as 34% and 11% respectively compared to 21% and 2% with nivolumab monotherapy[1]. IrAE affecting the gastrointestinal tract are currently managed using algorithms based on severity of symptoms. Mild, grade 1 events can generally be monitored and are managed expectantly. Grade 2-4 events require corticosteroid use, and may require withholding the immunotherapy agent in severe cases and the addition of immunomodulatory agents.

Steroid sparing agents such as mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), tacrolimus or infliximab are established treatment strategies, if no response is seen within 3-5 d[2,3]. Vedolizumab, an IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against α4β7 integrin has an established role in treating inflammatory bowel disease. It has been shown to be effective in immune-related colitis and in 2017, it was reported as an alternative to infliximab in the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines[2]. This case illustrates its use in the combined immunotherapy field, specifically after three failed attempts of immunomodulation with agents recommended in current guidelines.

A 27-year-old female with metastatic melanoma presented to the Emergency Department with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain and nausea 1 d after the fourth cycle of combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab.

The patient presented to the Emergency Department 24 h after cycle 4 with an acute onset of grade 3 diarrhea, per rectal (PR) bleeding, abdominal cramping, nausea and vomiting. She was already receiving oral prednisolone 50 mg daily for resolving grade 2 dermatitis and grade 2 hepatitis.

She was diagnosed with a superficial spreading melanoma of her forehead. This was excised in August 2017 and showed a Breslow thickness of 0.5 mm, Clark level III, without ulceration or lymphovascular invasion but positive margins requiring re-excision, achieving clear resection on reattempt.

The patient presented to the emergency department the following month with right upper quadrant pain, headache and mild generalized abdominal discomfort. Computed tomography (CT) chest and abdomen showed bilateral lung nodules and cystic-like structures in the pancreas and positron emission tomography (PET) showed uptake in bone, soft tissue, lung, pancreas, peritoneum, mesentery, left gluteal region and upper abdominal lymph nodes. Fine needle aspirate of the palpable gluteal soft tissue mass was consistent with metastatic melanoma (BRAF wild type). At time of diagnosis, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was mildly elevated at 296 IU/L and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain showed a T1 enhancing lesion measuring 13 mm × 12 mm in the left anterior temporal lobe without surrounding vasogenic oedema.

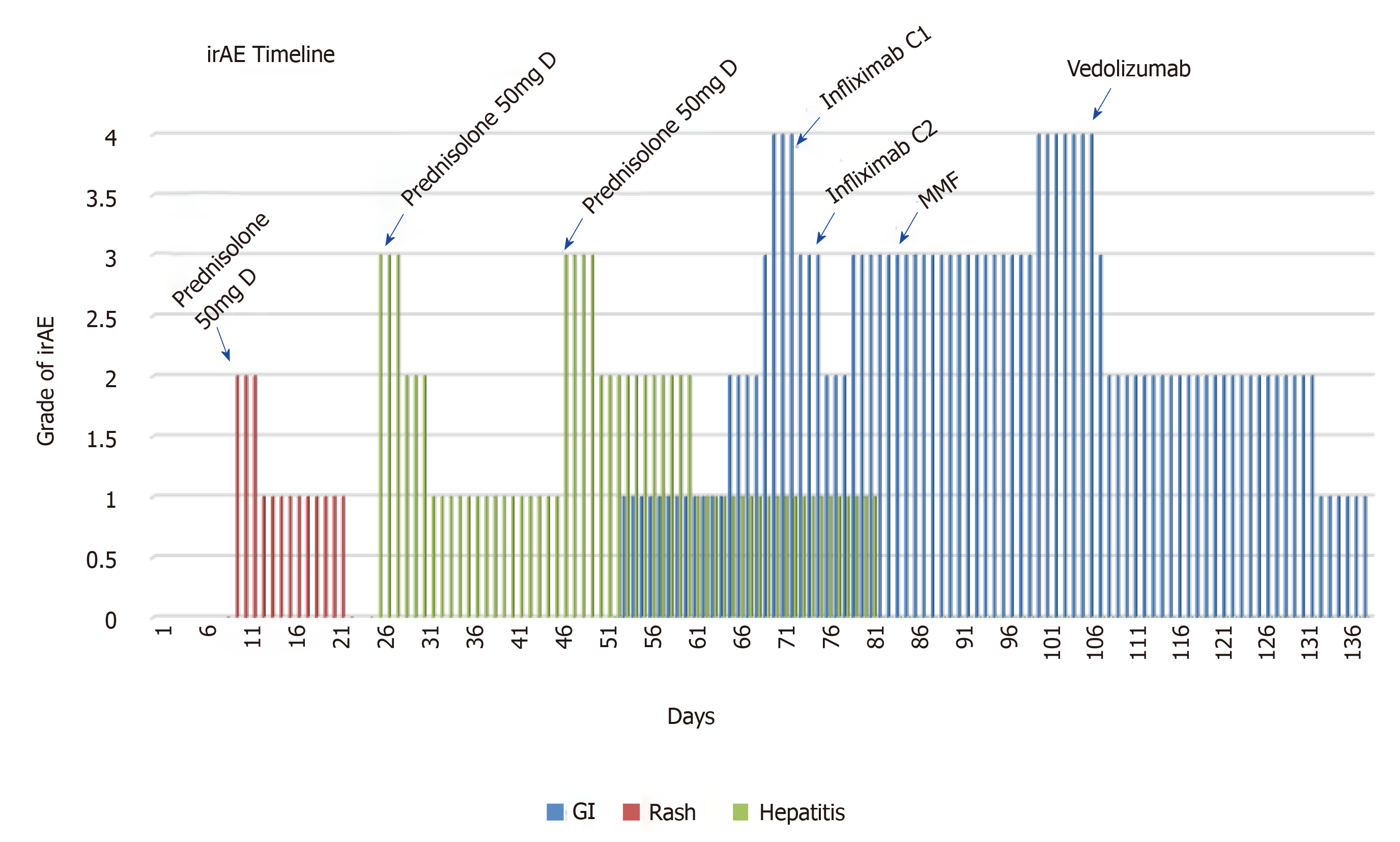

Given her age, BRAF status, high disease burden and good performance status, she was commenced on combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab. Post cycle 1, the patient presented with grade 2 dermatitis over the torso, face and limbs and was commenced on 50 mg prednisolone with prompt resolution. Over the following fortnight, steroids were tapered, LDH normalized and the left gluteal lesion was no longer palpable. After the second cycle, she complained of dizziness, nausea and anorexia. Liver function tests (LFTs) were deranged from a normal baseline with aspartate transaminase (AST) of 265 IU/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) of 233 IU/L, gamma glutamyl transferase of 185 IU/L and alkaline phosphatase of 203 IU/L. She was recommenced on 50mg prednisolone for grade 2 hepatitis. Cycle 3 proceeded while receiving 10 mg prednisolone given the patient was symptom free and LFTs were improving. This was however increased to 50 mg as the ALT again increased from 51 to 144. MRI brain performed at this time, showed a partial decrease in volume of the single brain metastasis. A decision was made by the neurosurgical team to continue surveillance MRI imaging given this early response. On day 65 (1 d after the 4th cycle), the patient presented with grade 3 colitis with diarrhea, PR bleeding, worsening abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting.

Her co-morbidities included asthma and an inflammatory arthropathy with previous steroid use (last acute flare 7 years prior). There was no significant family history.

Vital signs were within normal limits. There was generalized tenderness on abdominal palpation but no signs of peritonism. Rectal examination was normal.

Baseline laboratory results on the day of presentation to the Emergency Department were as follows: Fasting blood glucose 154 g/L; WCC 18.3 × 109/L; Plt 287 × 109/L; Neutrophils 14.84 × 109/L; Bilirubin 7 μmol/L; ALT 97 U/L; LDH 215 U/L; Albumin 39 g/L; Sodium 138 mmol/L; potassium 3.9 mmol/L; Creatinine 66 μmol/L; Urea 5.7 mmol/L; eGFR > 90; TSH 1.90 mu/L; fT3 3.4 pmol/L; fT4 12.2 pmol/L.

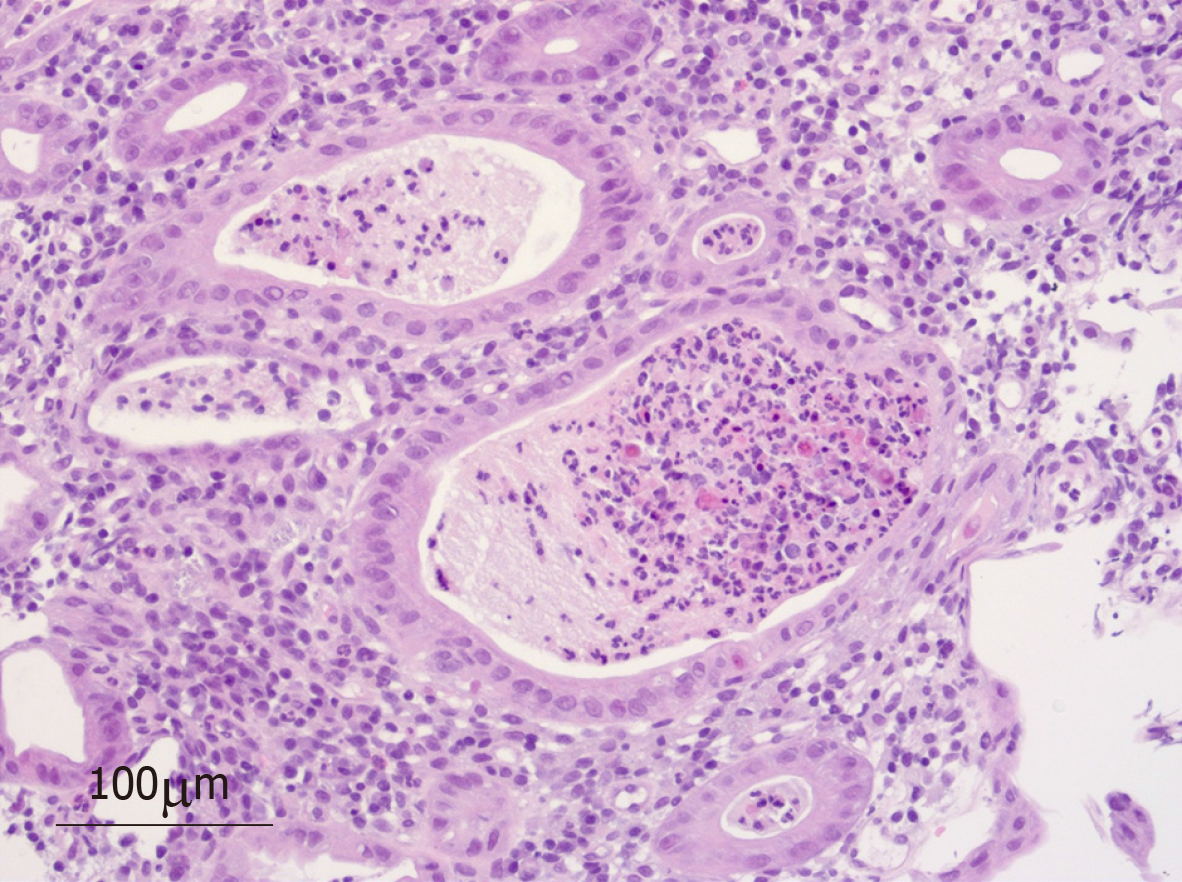

CT showed features of colitis and a reduction in the intra-abdominal metastases. Intravenous methylprednisolone was administered (1 g daily for 5 d, subsequently 1 mg/kg prednisolone maintenance) and despite this, an increase in frequency and severity of symptoms to grade IV was seen. Stool culture was negative and colonoscopy showed features consistent with acute colitis with patchy inflammation and ulceration macroscopically to the splenic flexure with no evidence of cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies on histopathology. Nine days after symptom onset, the first dose of infliximab was administered followed by a second dose 3 d later. Initially a reduction in frequency to 5 motions/d was seen, however symptoms worsened 3 d later. On day 20 after symptom onset, she commenced MMF 500 mg bd. Three days later, MMF was increased to 1 g bd with no improvement. A flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed, given concerns of perforation. Macroscopically, she had a high van der Heide score, on histology, increased cellularity of the lamina propria, apoptotic debris, neutrophilic infiltration and crypt abscesses were shown, with an absence of intraepithelial lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1).

0

0

0

Gastroenterology team was consulted within 24 h of emergency department presentation. Investigations including stool microscopy, culture and sensitivity were performed and steroid sparing agents administered as advised.

Diagnosis was confirmed by colonoscopy showing diffuse moderate inflammation in the sigmoid colon characterized by erosions, erythema, friability, granularity and a loss of vascularity (Figure 2) and histopathology of colonic biopsies showing neutrophilic crypt abscesses (Figure 1).

First dose of vedolizumab was administered 42 d from symptom onset resulting in marked attenuation of symptoms 3 d later. A second and third dose were given two weeks apart with complete resolution of diarrhea seen. No side effects were shown with this regime and complete resolution occurred before the third and final dose (Figure 3).

The patient did not commence maintenance nivolumab due to the severe immune related colitis. A post treatment PET showed near complete metabolic response with a stable MRI Brain and the patient returned to work. Twelve months from treatment, PET has shown an ongoing complete metabolic response.

Combined immunotherapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab is an established approach in higher risk metastatic melanoma, particularly in cases of M1d disease[4]. Other features favouring combination therapy include high LDH at time of diagnosis and high burden of particularly visceral disease[1]. Combined therapy is associated with higher rates of grade 3/4 toxicity compared to nivolumab monotherapy (59% vs 21%) with a discontinuation rate of 39.3% predominately due to treatment-related adverse effects[1].

Gastrointestinal toxicity is the most prevalent irAE seen in immunotherapy[1]. It is also the most common cause of grade 3/4 toxicities, occurring in 17% of patients on combined therapy and 4% of patients on nivolumab alone[1]. Colitis, defined as diarrhea, associated with either or both abdominal pain and endoscopic/radiological inflammation, is often the first event leading to discontinuation of therapy[3,5,6]. Up to half of these cases will be steroid-refractory necessitating further immunomodulation[7]. It remains challenging to predict who will get colitis and no correlation has been shown with abdominal pain, grade of diarrhea or endoscopic features and the requirement for infliximab[7]. Those with a high score on inflammatory indices, e.g., Van der Heide score on colonoscopy, bloody stools, presence of ulceration or pancolitis will more likely be steroid-refractory[7,8]. No biomarker has to date been consistently shown to predict risk for colitis. However, faecal calprotectin provides a non-invasive measurement of neutrophil flux to the intestine, however[5,7].

Recent literature has made efforts to describe the histology typically encountered in colitis induced by both PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors. This becomes particularly relevant in cases of diagnostic dilemma or in steroid-refractory patients. Findings may include increased lamina propria cellularity, neutrophilic infiltration, crypt abscesses and intraepithelial lymphocytosis usually in the absence of chronic inflammation[5,7]. In most series, the sigmoid is involved and is therefore a reliable biopsy site obtainable with flexible sigmoidoscopy. Particularly in severe cases, Geukes Foppen et al[9] advise against performing a colonoscopy if ulceration is seen in the lower colon, in order to avoid perforation. In the case of those without sigmoid involvement, in their analysis, 8% had ascending-only colitis on endoscopy[9]. A large proportion of cases studied also show concomitant upper gastrointestinal involvement on endoscopy[5,7,10].

In managing colitis, along with considering concomitant medications, the clinician must exclude infection with stool culture, cytomegalovirus screening via biopsy to rule out inclusion bodies, as well as contemplating the potential for gastrointestinal metastases[11]. As described in current published guidelines, the approach to grade 3/4 diarrhea/colitis, includes withholding the immune checkpoint inhibitor, commencing intravenous methylprednisolone 1-2 mg/kg and obtaining a gastroenterology consult and colonoscopy[2]. If no improvement is shown within 72 h, infliximab 5 mg/kg should be considered[2]. Infliximab as the standard treatment for steroid-refractory patients has a median time to response of 2 d as shown in the case series by Gonzalez et al[7].

Vedolizumab is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody that inhibits α4β7 integrin, disabling its interaction with mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 on intestinal vasculature and stopping T cell migration into the gut[12,13].

Vedolizumab’s landmark trial was in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease refractory to standard treatments, where it was administered intravenously at 0, 2, 6 wk then every 8 wk as maintenance[13,14]. It had a tolerable side effect profile with mild nasopharyngitis, headache, arthralgia, nausea and fatigue, but no increased rates of infection[12-14].

At the time our patient was treated, literature pertaining to the use of vedolizumab was scarce but was mentioned in several guidelines in the management of immune-related toxicities[15,16]. We have conducted a literature review by searching Pubmed upto April 2019 using the following search strategy: ((“vedolizumab”[Supplementary Concept] OR “vedolizumab” [All Fields]) AND (“cell cycle checkpoints”[MeSH Terms] OR (“cell”[All Fields] AND “cycle”[All Fields]) AND “checkpoints”[All Fields]) OR “cell cycle checkpoints”[All Fields] OR “checkpoint”[All Fields]) AND (“antagonists and inhibitors”[Subheading] OR (“antagonists”[All Fields] AND “inhibitors”[All Fields]) OR “antagonists and inhibitors”[All Fields] OR “inhibitors”[All Fields]))) AND (“colitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “colitis”[All Fields]).

In the context of immune-checkpoint therapy-induced colitis, one of the first case reports published assessing the use of vedolizumab was by Hsieh et al[17] in 2016. In the first case series published the year after by Bergqvist et al[18], 7 patients with melanoma or lung cancer were assessed. The median time from onset of enterocolitis to start of vedolizumab was 79 d and all patients had monotherapy with ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma[18]. All patients but one had a steroid-free remission with a median time of 56 d from first dose of vedolizumab[18]. The time to onset in our patient was 54 d and overlapped a resolving grade 2 hepatitis.

Abu-Sbeih et al[19] assessed outcomes of 28 patients receiving vedolizumab therapy and showed a longer duration of steroid use in patients receiving infliximab compared to no infliximab prior to vedolizumab (131 d compared to 85 d) and higher success rates in the latter group (67% compared to 95%). The median time from the first ICPI infusion to onset of diarrhea was 10 wk, mean duration of corticosteroid therapy was 96 d and median duration from first vedolizumab infusion to improvement of symptoms was 5 d[19].

Abu-Sbeih et al[20] also recently performed a retrospective review of patients at MD Anderson Cancer Centre receiving selective immunosuppressive therapy in patients with immune-mediated colitis. A total of 179 patients had colitis and 84 received selective immunosuppressive therapy[21]. Almost half of these patients had grade 3-4 colitis and 95% of patients who had faecal calprotectin tested yielded a positive result[20]. Fifty patients had infliximab and 34 patients had vedolizumab[20]. Rates of recurrence of symptoms were 15/50 in the infliximab group compared to 1/34 in the vedolizumab group[20]. However those receiving infliximab also had fewer infusions[20] which may explain this finding. The authors concluded that receiving infliximab rather than vedolizumab was a risk factor for recurrence after steroid weaning[20]. Furthermore, early introduction of selective immunosuppressive therapy in the disease course (i.e., < 10 d from onset of colitis) instead of waiting until failure of steroid therapy led to fewer hospitalizations and shorter duration of symptoms[20].

It is encouraging in this case that in spite of this severe episode of colitis, complete metabolic response has been shown on recent imaging despite treatment discontinuation. This correlation of severity of immune-related side effects and efficacy of treatment has been observed in a case series showing a higher response rate in those requiring early discontinuation of therapy due to immune-related toxicity (58.3% vs 50%)[21].

This case report adds to the available evidence supporting the use of vedolizumab in the setting of infliximab-refractory immune-mediated colitis. This is the first report in the literature in the combined immunotherapy setting whereby there were three unsuccessful attempts using standard immunomodulatory agents.

Although there have been recent publications in this area, given the increasing indications for immunotherapy in multiple tumour types, further research is still needed in the prospective setting with larger patient groups.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tang Y S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF, Smylie M, Dummer R, Hill A, Hogg D, Haanen J, Carlino MS, Bechter O, Maio M, Marquez-Rodas I, Guidoboni M, McArthur G, Lebbé C, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Cebon J, Sosman J, Postow MA, Callahan MK, Walker D, Rollin L, Bhore R, Hodi FS, Larkin J. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2362] [Cited by in RCA: 2775] [Article Influence: 346.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, Kerr KM, Peters S, Larkin J, Jordan K; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv119-iv142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1607] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 187.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Spain L, Diem S, Larkin J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;44:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 544] [Cited by in RCA: 638] [Article Influence: 70.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, Hamid O, Hodi FS, Moschos SJ, Khushalani NI, Lewis K, Lao CD, Postow MA, Atkins MB, Ernstoff MS, Reardon DA, Puzanov I, Kudchadkar RR, Thomas RP, Tarhini A, Pavlick AC, Jiang J, Avila A, Demelo S, Margolin K. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Melanoma Metastatic to the Brain. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:722-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 960] [Cited by in RCA: 979] [Article Influence: 139.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta A, De Felice KM, Loftus EV, Khanna S. Systematic review: colitis associated with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:406-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2691-2697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1058] [Cited by in RCA: 1107] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gonzalez RS, Salaria SN, Bohannon CD, Huber AR, Feely MM, Shi C. PD-1 inhibitor gastroenterocolitis: case series and appraisal of 'immunomodulatory gastroenterocolitis'. Histopathology. 2017;70:558-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jain A, Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Brant SR, Lazarev MG. Colonic ulcerations may predict steroid-refractory course in patients with ipilimumab-mediated enterocolitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2023-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Geukes Foppen MH, Rozeman EA, van Wilpe S, Postma C, Snaebjornsson P, van Thienen JV, van Leerdam ME, van den Heuvel M, Blank CU, van Dieren J, Haanen JBAG. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open. 2018;3:e000278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marthey L, Mateus C, Mussini C, Nachury M, Nancey S, Grange F, Zallot C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Rahier JF, Bourdier de Beauregard M, Mortier L, Coutzac C, Soularue E, Lanoy E, Kapel N, Planchard D, Chaput N, Robert C, Carbonnel F. Cancer Immunotherapy with Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies Induces an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Som A, Mandaliya R, Alsaadi D, Farshidpour M, Charabaty A, Malhotra N, Mattar MC. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: A comprehensive review. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:405-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 12. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Lukas M, Fedorak RN, Lee S, Bressler B, Fox I, Rosario M, Sankoh S, Xu J, Stephens K, Milch C, Parikh A; GEMINI 2 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1416] [Cited by in RCA: 1564] [Article Influence: 130.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Axler J, Kim HJ, Danese S, Fox I, Milch C, Sankoh S, Wyant T, Xu J, Parikh A; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1576] [Cited by in RCA: 1864] [Article Influence: 155.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Khanna R, Feagan, B. Vedolizumab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Investigation. 2015;5:247-255. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thompson JA. New NCCN Guidelines: Recognition and Management of Immunotherapy-Related Toxicity. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:594-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, Bingham CO, Brogdon C, Dadu R, Hamad L, Kim S, Lacouture ME, LeBoeuf NR, Lenihan D, Onofrei C, Shannon V, Sharma R, Silk AW, Skondra D, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wang Y, Wiley K, Kaufman HL, Ernstoff MS; Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Toxicity Management Working Group. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1337] [Cited by in RCA: 1417] [Article Influence: 177.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hsieh AH, Ferman M, Brown MP, Andrews JM. Vedolizumab: a novel treatment for ipilimumab-induced colitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bergqvist V, Hertervig E, Gedeon P, Kopljar M, Griph H, Kinhult S, Carneiro A, Marsal J. Vedolizumab treatment for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:581-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abu-Sbeih H, Ali FS, Alsaadi D, Jennings J, Luo W, Gong Z, Richards DM, Charabaty A, Wang Y. Outcomes of vedolizumab therapy in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: a multi-center study. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abu-Sbeih H, Ali FS, Wang X, Mallepally N, Chen E, Altan M, Bresalier R, Charabaty A, Dadu R, Jazaeri A, Lashner B, Wang Y. Early introduction of selective immunosuppressive therapy associated with favourable clinical outcomes in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:93. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Carlino MS, Sandhu S. Safety and Efficacy Implications of Discontinuing Combination Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3792-3793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |