Published online Feb 6, 2018. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v9.i1.8

Peer-review started: March 23, 2017

First decision: May 3, 2017

Revised: August 2, 2017

Accepted: November 9, 2017

Article in press: November 9, 2017

Published online: February 6, 2018

Processing time: 318 Days and 9.4 Hours

To describe trends of combination therapy (CT) of infliximab (IFX) and immunomodulator (IMM) for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the community setting.

A retrospective study was conducted of all IBD patients referred for IFX infusion to our community infusion center between 04/01/01 and 12/31/14. CT was defined as use of IFX with either azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or methotrexate. We analyzed trends of CT usage overall, for Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), and for the subgroups of induction patients. We also analyzed the trends of CT use in these groups over the study period, and compared the rates of CT use prior to and after publication of the landmark SONIC trial.

Of 258 IBD patients identified during the 12 year study period, 60 (23.3%) received CT, including 35 of 133 (26.3%) induction patients. Based on the Cochran-Armitage trend test, we observed decreasing CT use for IBD patients overall (P < 0.0001) and IBD induction patients, (P = 0.0024). Of 154 CD patients, 37 (24.68%) had CT, including 20 of 77 (26%) induction patients. The Cochran Armitage test showed a trend towards decreasing CT use for CD overall (P < 0.0001) and CD induction, (P = 0.0024). Overall, 43.8% of CD patients received CT pre-SONIC vs 7.4% post-SONIC (P < 0.0001). For CD induction, 40.0% received CT pre-SONIC vs 10.8% post-SONIC (P = 0.0035). Among the 93 patients with UC, 19 (20.4%) received CT. Of 50 induction patients, 14 (28.0%) received CT. The trend test of the 49 patients with a known year of induction again failed to demonstrate any significant trends in the use of CT (P = 0.6).

We observed a trend away from CT use in IBD. A disconnect appears to exist between expert opinion and evidence favoring CT with IFX and IMM, and evolving community practice.

Core tip: In our 13 year experience at a community hospital infusion center, approximately 26% of inflammatory bowel disease patients receiving infliximab infusions received concomitant immunomodulator therapy. This is comparable to rates of combination therapy (CT) at major tertiary referral centers. However, there was a trend of decreased utilization of CT over the study period, even following the publication of SONIC. This suggests a need for further study to define the population with the most favorable risk-benefit ratio from CT, as well as the need for more direct guidelines from major societies.

- Citation: Berkowitz JC, Stein-Fishbein J, Khan S, Furie R, Sultan KS. Declining use of combination infliximab and immunomodulator for inflammatory bowel disease in the community setting. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2018; 9(1): 8-13

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v9/i1/8.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v9.i1.8

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) together comprise most cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The prevalence of IBD in the United States appears to be increasing, and it is currently estimated at 1 in 300 individuals, or roughly 1.5 million members of the population[1]. For both CD and UC, treatment of moderate to severe disease often includes the use of corticosteroids for induction of clinical remission, with guidelines recommending transitioning patients off corticosteroids and using an immunomodulator (IM) such as 6-mercaptupurine (6-MP), azathioprine (AZA) for either CD or UC, or methotrexate (MTX) for CD, to maintain remission[2] For those failing to maintain steroid free clinical response or remission with IM, the addition or substitution of the newer biologic therapies comprise the next step in what is now commonly referred to as a “step up” approach to IBD therapy.

Infliximab (IFX) was introduced as the first biologic therapy targeting TNF-α. Initially approved in the United States for CD in 1997, approval for UC followed in 2005[3]. Though IFX has been followed by other TNF-α inhibitors, and newer biologics targeting alternate pathways, IFX is still among the most widely used biologic therapies[4]. IFX and the other biologics are increasingly viewed as an alternative to steroid and IM therapy as part of a “top down” therapeutic approach, which has been shown to reduce patients’ steroid exposure as well as potentially improving overall clinical outcomes[5].

Early studies suggested a potential therapeutic benefit to combination therapy (CT) utilizing both IFX and IM, mainly through reduction of antibodies to IFX (ATI), reduced infusion reactions and higher IFX trough levels[6]. A major turning point was the SONIC study. While earlier work examined the role of IM combined with anti TNF-α mostly in those with IM exposure and failure prior to stepping up to IFX, SONIC focused on induction therapy among patients naïve to both biologic and IM with CD. Patients were randomized to receive either IFX, AZA or CT with both agents. CT was found to be superior to monotherapy with either IFX or AZA for the induction of steroid free clinical remission, without any increase in adverse events[7]. More recently the UC SUCCESS trial has demonstrated a similar benefit to combing AZA with IFX in those with UC[8].

Since the publication of SONIC, key thought leaders[9] and major society guidelines[10] have increasingly advocated for the use of CT, but it is unclear to what extent community practice has changed, balanced against reports of opportunistic infections[11], and cases of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) with CT[12,13]. Currently, little is known regarding the adoption of CT in the community setting. Our main goal was to analyze the trends over time of CT usage for IBD overall, CD and UC. As a secondary goal we sought to examine whether the publication of the SONIC trial has had any impact on the proportion of CT use for CD in the community setting.

The Northwell Health Center for Infusion Medicine, part of the Division of Rheumatology, provides IFX infusion services on behalf of both Northwell Health faculty and community gastroenterologists. Patients referred for IFX include both those beginning therapy at the center, as well as those switching their infusion therapy from another location. Center protocol requires that all physician referrals must include the completed standardized medical history form specifying IBD type, along with signed orders for IFX dose, schedule and pre-infusion medications. The standardized form includes a medication history section which specifically asks the referring physician to record either past or current use of AZA, 6-MP, MTX, without specifying dose, as well as other commonly used IBD medications. Following the initiation of IFX, updated versions of the standardized medical history are not performed.

We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients receiving IFX infusions at the center from 01/01/2002 until 12/31/2014. Inclusion criteria required a diagnosis of CD, UC or indeterminate colitis (IC), receipt of at least 1 IFX infusion at the center, age of 18 years or greater, and availability of a completed standardized medical history form.

In addition to IBD type, patients were subcategorized as induction or maintenance patients based on the schedule of the infusions they received. Induction patients were those whose first infusion was part of a documented standard week 0, 2, and 6 induction regimen. All other patients were grouped in the maintenance cohort. CT for both induction and maintenance patients was defined by IM use at first IFX dose at the infusion center. Descriptive analysis was performed of the overall group including both induction and maintenance IBD patients, as well as for the subgroup limited to induction patients. Similar analyses were performed by CD and UC subgroups. For the secondary analysis comparing usage of CT therapy pre vs post SONIC, a patient was considered a pre-SONIC patient if they presented to the infusion center before April 2010.

The proportions of CT use in the induction and maintenance groups were calculated for all patients as well as for CD and UC separately. In secondary analyses we stratified patients based on years of age (< 35, 35-60, > 60), diagnosis (UC vs CD), gender and faculty status of the prescribing physician (faculty vs community) to investigate for any disparities in CT utilization between subgroups.

The infusion records of 293 IBD patients were reviewed. Of these, 10 were excluded due to incompleteness of the infusion record, and 25 were excluded due to a missing record of concurrent medications, leaving 258 for analysis. The patients were referred by 57 gastroenterologists (mean and median patients per gastroenterologist of 4.54 and 2 respectively). Patient demographics are detailed in Table 1. 154 (59.7%) had CD, 93 (36.1%) had UC. Eleven patients had IC, and these patients were included in the overall analysis but excluded from the disease-specific analyses. For two subjects, one each with CD and UC, infusion pre vs post April 2010 was confirmed without exact date of first dose. These patients were excluded from the analyses of trends in CT use over time.

| IBD1 | CD | UC | |

| Total | 258 | 154 | 93 |

| Male | 127 (49.2) | 78 (50.6) | 48 (51.6) |

| Mean age, yr | 40.88 ± 16.67 | 39.59 ± 16.28 | 43.66 ± 17.04 |

| IFX Pre-SONIC | 111 (43.0) | 73 (47.4) | 30 (32.2) |

| 6-MP/AZA use | 56 (21.7) | 35 (22.7) | 18 (19.4) |

| MTX use | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.1) |

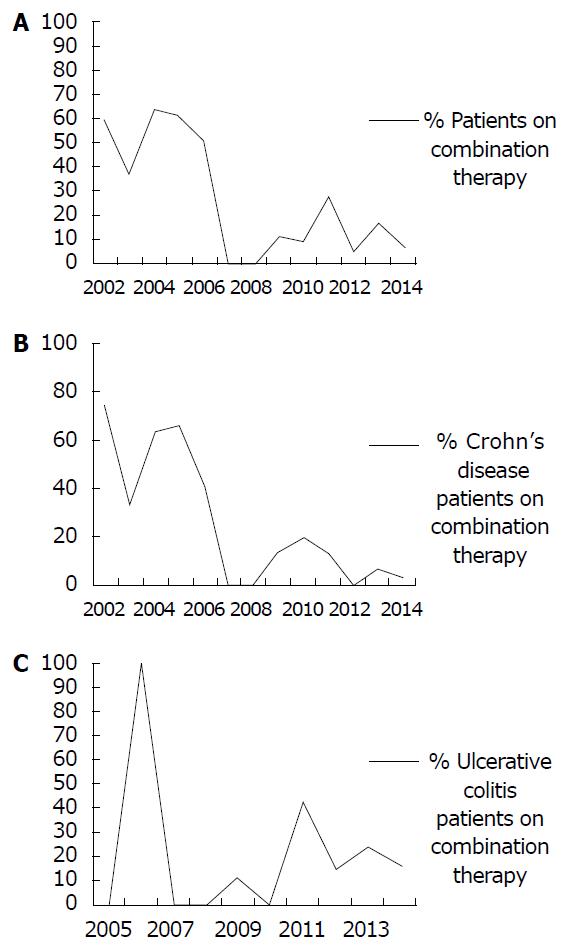

Among the total group of 258 patients with IBD, 60 (23.3%) received CT at the time of first IFX infusion at our center. The Cochran-Armitage trend test of the 256 patients with a known year of first infusion demonstrated a significant decrease in the use of CT for all IBD patients over the 13 year period, from 2002 to 2014, P < 0.0001 (see Figure 1A). The IBD induction group included 133 patients of whom 35 (26.3%) received CT. The trend test of the 131 subjects in the IBD induction group with a known year of induction again demonstrated a significant decreasing trend in the use of CT, P = 0.0024.

For the 258 total IBD group 111 (43.0%) had their induction or maintenance regimen start pre-SONIC compared with 147 (57.0%) post-SONIC. Due to evidence of effect modification (EM) of the patient’s IBD diagnosis type on the relationship between induction time period (pre vs post-SONIC trial) and use of CT (P = 0.01), analyses comparing pre vs post-SONIC trial were stratified by disease type. Stratum-specific results for CD are reported below.

Among the 154 patients with CD, 37 (24.0%) received CT at the time of first infusion. The Cochran-Armitage trend test of the 153 patients with a known year of first infusion demonstrated a significant decrease in the use of CT over the 13 year period, from 2002 to 2014, P < 0.0001 (see Figure 1B). The CD induction group included 77 patients of whom 20 (26.0%) received CT. The trend test of the 76 subjects with a known year of induction again demonstrated a significant decreasing trend in the use of CT, P = 0.0024. The proportion of all CD patients receiving CT was greater pre vs post-SONIC (43.8% vs 7.4%, respectively, P < 0.0001) as well as for the induction only group (40.0% vs 10.8%, respectively, P = 0.0035).

Among the 93 patients with UC, 19 (20.4%) received CT at the time of first infusion. The Cochran-Armitage trend test of the 92 patients with a known year of first infusion did not demonstrate any significant trends in the use of CT over time, P = 0.9 (see Figure 1C). The UC induction group included 50 patients of whom 14 (28.0%) received CT. The trend test of the 49 patients with a known year of induction again failed to demonstrate any significant trends in the use of CT, P = 0.6.

There were no statistically significant differences in the proportions of CT use across the study period, among CD patients or UC patients, according to age group, gender, faculty status of the referring gastroenterologist, use of other agent or steroid use (P > 0.05 for all tests); results not shown.

Despite the positive effects offered by CT for CD in the SONIC population, and for UC by UC SUCCESS, it is unclear to what degree the use of CT has been adopted into clinical practice. A recent review from 7 high volume IBD referral centers, comprising 1659 patients with CD and 946 with UC, showed a wide range of adoption of CT. Among CD patients the use CT overall was 21%. There was a significant variation of usage across all centers ranging between 8% and 32%, with a 95%CI: 3.15 (1.79-5.56). Among UC patients the use of CT overall was 9%, with no significant variation of usage seen, ranging between 6% and 13%, CI 1.14 (0.48-2.78)[14].

Our findings offer a different perspective by which to view the question of CT usage, by providing 13 years of follow up data addressing the adoption of CT in the community setting. Examining a mixed cohort of 258 patients of whom 154 had CD, all receiving IFX, we found that CT was employed at the beginning of therapy in 23.3% of patients overall. Notably, we observed a significant trend of decreasing use of CT for IBD generally, in the CD cohort, as well as for the subgroup of CD patients receiving induction therapy.

Much like the findings from the referral center consortium, we suspect that these findings do not reflect a lack of awareness on the part of community gastroenterologists with the SONIC trial. More likely, it reflects a deeper understanding of what the SONIC results specifically support; the value of CT in a subset of treatment naïve patients. It is also likely that persistent concerns regarding adverse events with CT exert a strong pull away from CT even in cases where it may be appropriate. Though it is still uncertain if CT increases Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma rates overall as compared to thiopurine monotherapy[15], it is now accepted that CT increases the risk of Hepatosplenic T Cell Lymphoma (HSTCL). While exceedingly rare, a recent systematic review found that 20 of 36 documented cases of HSTCL occurred in patients with a history of CT use[13]. Evidence of this association began to accumulate in 2007, which coincides with the temporary disappearance of CT use for our patients at that time[16]. Despite risk-benefit analyses favorable to CT accounting for lymphoma[17] - the preferences of physicians and/or patients have likely been impacted, particularly when faced with a black box warning addressing HSTCL found in the IFX packaging insert. Even if one is to accept the benefit of CT for induction, there is still uncertainty regarding the appropriate duration of IMM for maintenance[18]. This uncertainty may itself serve as a barrier to choosing CT over anti-TNF-α monotherapy.

The main weaknesses of our findings are mainly those which are inseparable from the retrospective study design. While our primary aim was simply observational, examining trends of CT usage over time, we specifically singled out the publication of SONIC as a time point for analysis and comparison. Given the impact of SONIC on clinical thinking we believe this to be fair, but since we did not have data on disease duration or history of prior IMM use, it is unknown how our study population compared to those in SONIC. Especially for those patients infused during the earlier years of the analysis, it is very likely that many had a longer disease duration and past IMM use, unlike those patients in the SONIC cohort. A history of failure or intolerance to prior IMM could not be accounted for, and would tend to lower the use of CT for those beginning IFX. Also, as we defined induction by a specific schedule of IFX infusions at 0, 2, and 6 wk, we were unable to account for those receiving induction therapy with a non standard regimen, nor were we able to differentiate those receiving a first time induction regimen verses those who may have been receiving re-induction with IFX. Also, our inability to track medication changes other than IFX over time prevents us from observing the rate of CT usage at any time point during IFX therapy. I.e. we have no way of knowing how many of our patients beginning IFX mono-therapy may have “stepped up” to CT over time. Also, while we did a pre vs post SONIC analysis for IBD overall, this result of course included patients with UC, which the SONIC trial did not address. Finally, with 57 prescribing gastroenterologists identified it would appear that we have a fair overview of local community practice, but the community itself is narrowly defined and may not be reflective of prescribing trends in other regions.

In summary, we present the results of our analysis of community prescribing trends of CT with IFX and IMM for IBD overall, CD and UC. Over the 13 year period examined we observed a significant trend away from usage of CT with IFX and IMM for IBD overall and for CD patients specifically. It is likely that balanced against the benefit of CT observed in the SONIC cohort are the daily concerns of both patients and their physicians regarding HSTCL risk and the uncertainty of optimal duration of IMM use along with IFX. Further investigation regarding these issues, as well as a clearer demonstration of benefit in non treatment native patients, will be needed to support any future expanded use of CT.

The SONIC trial demonstrated the superiority of combination immunomodulator and biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease (CD). Further studies evaluated the efficacy of combination therapy (CT) in ulcerative colitis. There are concerns regarding the safety of CT, specifically the risks of infection and malignancy.

Little is known about the degree of utilization of CT in the community setting. It is also unknown whether the publication of the SONIC trial impacted rates of CT usage.

This study demonstrates that the utilization of CT has generally trended down over the past decade. It also demonstrates that the publication of the SONIC study did not lead to an increase in the utilization of CT.

The decline in CT utilization highlights the need for further studies to define the ideal patient population for CT, as well as the need for more definitive guidelines from professional societies.

Combination therapy refers to the concurrent use of an immunomodulator, such as azathioprine, with a biologic drug, such as infliximab, in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Katsanos KH, Sorrentino D S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF

| 1. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3789] [Cited by in RCA: 3527] [Article Influence: 271.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465-483; quiz 464, 484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Park KT, Sin A, Wu M, Bass D, Bhattacharya J. Utilization trends of anti-TNF agents and health outcomes in adults and children with inflammatory bowel diseases: a single-center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1242-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lémann M, Mary JY, Duclos B, Veyrac M, Dupas JL, Delchier JC, Laharie D, Moreau J, Cadiot G, Picon L, Bourreille A, Sobahni I, Colombel JF; Groupe d’Etude Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Infliximab plus azathioprine for steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1054-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Van Assche G, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, D’Haens G, Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Ternant D, Watier H, Paintaud G, Rutgeerts P. Withdrawal of immunosuppression in Crohn’s disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1861-1868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2539] [Cited by in RCA: 2376] [Article Influence: 158.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, Márquez JR, Scott BB, Flint L, van Hoogstraten HJ, Chen AC, Zheng H, Danese S. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:392-400.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 695] [Article Influence: 63.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Colombel JF. Understanding combination therapy with biologics and immunosuppressives for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:486-490. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease evaluation and treatment: clinical decision tool. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:702-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Egan LJ. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:929-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 719] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, Tian H, Sandborn WJ. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kotlyar DS, Osterman MT, Diamond RH, Porter D, Blonski WC, Wasik M, Sampat S, Mendizabal M, Lin MV, Lichtenstein GR. A systematic review of factors that contribute to hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:36-41.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Kwon J, Raffals L, Sands B, Stenson WF, McGovern D, Kwon JH, Rheaume RL, Sandler RS. Variation in treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases at major referral centers in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1197-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. Insufficient evidence to conclude whether anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy increases the risk of lymphoma in Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mackey AC, Green L, Liang LC, Dinndorf P, Avigan M. Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma associated with infliximab use in young patients treated for inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:265-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Siegel CA, Finlayson SR, Sands BE, Tosteson AN. Adverse events do not outweigh benefits of combination therapy for Crohn’s disease in a decision analytic model. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Colombel JF. When should combination therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease be discontinued? Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:259-262. [PubMed] |