Published online Nov 6, 2016. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i4.579

Peer-review started: April 13, 2016

First decision: July 20, 2016

Revised: August 7, 2016

Accepted: September 13, 2016

Article in press: September 15, 2016

Published online: November 6, 2016

Processing time: 202 Days and 14.5 Hours

Osteonecrosis is a very rare complication of Crohn’s disease (CD). It is not clear if it is related to corticosteroid therapy or if it occurs as an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. We present the case of a patient with CD who presented with osteonecrosis of both knees. A 22 years old woman was diagnosed with CD in April 2012 (Montreal Classification A2L1 + L4B3p). She was started on prednisolone (40 mg/d), azathioprine (100 mg/d) and messalazine (3 g/d). In July 2012, due to active perianal disease, infliximab therapy was initiated. In September 2012, she had a pelvic abscess complicated by peritonitis and an ileal segmental resection and right hemicolectomy were performed. In December 2012 she was diagnosed with bilateral septic arthritis of both knees with walking impairment. She was treated with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, started a physical rehabilitation program and progressively improved. However, then, bilateral knee pain exacerbated by movement developed. Magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple osseous medullary infarcts in the distal extremity of the femurs, proximal extremity of the tibiae and patellas and no signs of subchondral collapse, which is consistent with osteonecrosis. The patient recovered completely and maintains therapy with azathioprine and messalazine. A review of the literature is also done.

Core tip: Although very rare, osteonecrosis is a devasting event that can occur in Crohn’s disease (CD). We present the case of a 22 years old woman with CD who was diagnosed with osteonecrosis of both knees. As we demonstrate with this report, awareness of risk factors, such as corticosteroid therapy and inflammatory bowel disease activity, is crucial to establish the diagnosis of this inflammatory bowel disease rheumatological complication. Prompt treatment is recommended. A review of the literature is also presented.

- Citation: Barbosa M, Cotter J. Osteonecrosis of both knees in a woman with Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7(4): 579-583

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v7/i4/579.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i4.579

Osteonecrosis or avascular necrosis is defined as cellular death of bone components due to interruption of blood supply. Consequently, there is a collapse and destruction of articular surfaces, pain and disability[1]. Epiphysis of long bones (femoral and humeral heads and femoral condyles) are primarily involved, with the hip being the most commonly affected joint. Several clinical entities (connective tissue disorders, hemoglobinopathies, coagulation disorders, pregnancy, alcohol abuse, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and corticosteroid use) have been associated with osteonecrosis, but its pathophysiology is not completely understood[2]. The true incidence of this rare manifestation in IBD is not known[1]. It has been reported to range from 0.5% to 4.3%[3]. We present the case of a 22 years old woman with Crohn’s disease (CD) who was diagnosed with osteonecrosis of both knees.

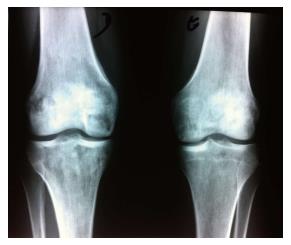

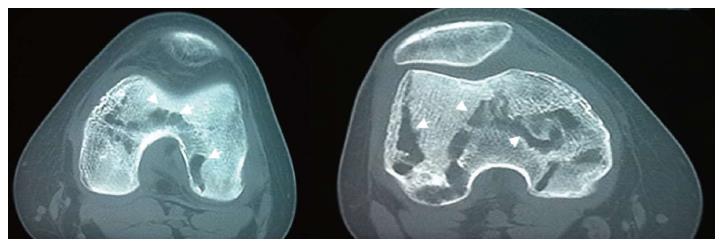

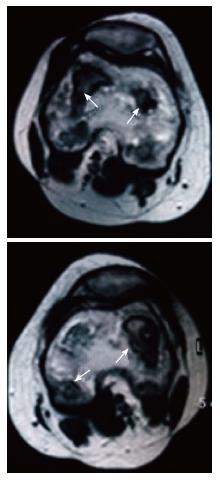

A 22 years old woman was diagnosed with CD in April 2012 (Montreal Classification A2L1 + L4B3p - diagnosis at 22 years-old; ileal plus jejunal involvement; penetrant behavior and perianal disease - rectovulvar fistulae). She was initially treated with prednisolone (40 mg/d), azathioprine (100 mg corresponding to 2 mg/kg per day) and messalazine (3 g/d). In July 2012, due to fistulae non-healing, a seton was placed and infliximab therapy was started (three infusions - 0, 2 and 6 wk - 5 mg/kg). Complete closure of the rectovulvar fistulae was then confirmed. In September 2012, she had had a pelvic abscess complicated by peritonitis and she was operated. Drainage of the abscess, ileal segmental resection and right hemicolectomy was performed. From April 2012 to December 2012 a gradual weaning of corticosteroid therapy was done. In December 2002 she presented with fever, intense pain, swelling and stiffness of both knees and impaired range of motion for six weeks. Bilateral articular effusions were observed. She got bedridden. There was no history of arthritis. Laboratory studies revealed a leucocytosis with neutrophilia (17.000/mm3 per 89%) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (28 mm3 per hour). Bilateral arthrocentesis was performed with diagnostic and drainage intent. Synovial fluid was purulent. Culture of the synovial fluid was positive for S. pneumoniae. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid and analgesia (acetaminophen and tramadol) was begun. Bilateral arthrotomy of knees with biopsy of the synovium was performed. The histological examination of the synovial tissue revealed synoviocyte hyperplasia, inflammatory infiltrate, mainly composed by polymorphonuclear neutrophils, and purulent exudates; these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of bilateral septic arthritis. There was no exacerbation of intestinal symptoms of CD. After an initial period of immobilization, she was started on a physical rehabilitation program and progressively improved: Inflammatory signs of knees disappeared and she started to walk with crutches. However, bilateral knee pain developed, exacerbated by movement, mainly at climbing stairs. Plain film radiographies of the knees demonstrated multiple bilateral hypotransparent areas in the distal extremity of the femurs, in the proximal extremity of the tibiae and in the patellas and also absence of signs of subchondral collapse (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple lacunar areas in the same localizations (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a “geographic” pattern resulting from multiple osseous medullary infarcts in the distal 15 cm of the femurs, in the proximal 10 cm of the tibiae and in the patellas; there were also no signs of subchondral collapse (Figures 3-5). These imagiologic findings were consistent with the diagnosis of osteonecrosis. The total body radionuclide bone scan (methylene biphosphonate labeled with technetium-99m) revealed an increased uptake of the agent in the distal ephiphysis of the femurs, in the proximal epiphysis of the tibiae and in the patellas; it also excluded other focus of the disease. A stage 2 of Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) was established. The peripheral blood smear was normal. Lipid levels (cholesterol and triglycerides) were within normal range. Antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antismooth muscle antibody and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. Procoagulant factors (C and S proteins, antithrombina III and V Leiden factor) were normal. The patient recovered completely and maintains therapy with azathioprine and messalazine.

The etiology and pathogenesis of osteonecrosis in IBD remain to be elucidated[3]. Some risk factors have been implicated, such as corticosteroid therapy[1,3,4] (systemic and topic) and disease activity so it can be considered an extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD[5,6]. Several studies report the occurrence of osteonecrosis in IBD patients either during or after corticosteroids use. Although initial data described a six to eight months period after initiating therapy for steroid-associated osteonecrosis to occur, this temporal relationship was not confirmed afterwards, with some other reports describing an erratic pattern of development[6]. No clear dose-response is established[1,3] but, corticosteroids doses are significantly higher in patients with osteonecrosis than in those without it[1,4,7]. Moreover, this complication may present with lower dosage of corticosteroids, comparing with other conditions[1]. All in all, a more precise association between corticosteroid use in IBD and osteonecrosis is still needed[3]. IBD patients can develop osteonecrosis unrelated to corticosteroid therapy. CD is associated with a hipercoagulable state, mainly during periods of active disease[5]; the fibrin microclots may lead to osteonecrosis by occluding epiphyseal capillaries and limiting the blood supply to the bone. This predisposition to thrombosis supports the hypothesis that osteonecrosis might be a rheumatological condition associated with IBD, rather than a complication of its treatment. Several risk factors can be simultaneously present. Our patient needed a relatively prolonged course of corticosteroid therapy and CD was still not in complete remission before the development of osteonecrosis. In this particular case, the event of bilateral septic arthritis, almost certainly secondary to the immunossupression therapy (corticosteroids, azathioprine and infliximab), might also have contributed to its occurrence.

Pain in the affected joint, usually exacerbated by weight-bearing, is typically the presenting symptom, although patients can remain entirely asymptomatic. Despite being initially mild, pain progressively worsens over time, being present at rest, and a decrease range of motion results[1,8]. Early diagnosis is important as treatment might avert disease progression[2,9]. However, it may be challenging, as 4% to 17% of patients with CD have type 1 - pauci-articular arthropathy, in which large bearing weight joints (ankles, knees, hips, wrists, elbows and shoulders) are affected[10]. A high index of suspicion in patients with risk factors is therefore mandatory[1]. This patient had well established risk factors for osteonecrosis, the persistence of bilateral knee pain despite the disappearance of the other inflammatory signs led us to investigate the possibility of this bone complication.

Diagnosis can be made by plain film radiographs, radionuclide bone scan, CT, MRI or invasive techniques (bone marrow pressure, stress test with injection of saline, intramedullary venography, superselective angiography and bone biopsy), the later being reserved for selected cases. At present, the goldstandard for the diagnosis of osteonecrosis is MRI, as it can depict the earliest imagiologic changes of the disease, with the best sensitivity and the best accuracy (75%-100%) compared with the other methods[1,3]. MRI shows a decreased signal intensity in both T1- and T2-weighted images[1,8,11]. Plain film radiographs are usually initially unremarkable[1,8]; afterwards they can demonstrate cystic or sclerotic changes, subchondral fractures (the “crescent sign”) and eventually secondary osteoarthritic changes[8]. Radionuclide bone scan using a bone-imaging agent (labeled with technetium-99m) is another helpful diagnostic imaging study in early stages of osteonecrosis[1,8], when plain films radiographs are normal or nearly normal. It is of utmost usefulness at screening, because bone scan can detect asymptomatic joint involvement[12]. However, it has the disadvantage of being non-specific, except when it shows a central area of decreased uptake surrounded by an area of increased uptake[8]. CT is a good technique at evaluating disease extension[8]. IBD patients tend to present with multifocal osteonecrosis[1,4]. Histology is the definitive method for the diagnosis of osteonecrosis, although it is usually unnecessary. Histological changes are encountered in both cortical bone and bone marrow. Necrosis of bone tissue (disappearance of the osteocytes) is followed by a regenerative process in surrounding tissues. Bone marrow lesions include edema, hemorrhage, fibrilloreticulosis, hipocellularity, necrosis of hematopoietic cells and replacement of adipocytes by eosinophilic debris[8]. The most commonly accepted classification system to stage osteonecrosis was devised by the ARCO. It encompasses 4 stages. The first one, stage 0, is defined as the presence of histological changes without any associated clinical signs or symptoms. In the last one, stage 4, there is evidence of progression to osteoarthritis (joint space narrowing and complete joint destruction)[13]. In our case, diagnosis was made by plain film radiographs, CT and MRI. A stage 2 of ARCO was established. In order to screen other localizations for osteonecrosis, a radionuclide bone scan was undertaken, which did not reveal other foci of the disease. No underlying analytical risk factor of any type (including any thrombophilic disorders) was found.

Management depends on the location and severity of joint involvement[1,8]. Conservative treatment includes restriction of weight-bearing on the affected joint or even immobilization, strengthening of the muscles surrounding the affected bone and analgesia[1,8]. No drug treatment has proven effective in averting disease progression, although bisphosphonates have shown some promise[14]. Surgical approaches include arthroplasty, core decompression, osteotomies and non-vascularized and vascularized bone grafting. In advanced cases, following subchondral collapse, total arthroplasty is the main surgical solution, although failure rates in patients with osteonecrosis are significantly higher in comparison with other conditions[1,8].

Conservative management was successful in our patient. She resumed walking without crutches and normal daily activities a few months later.

Regarding prevention, whenever possible, steroid-sparing agents should be the first option[8]. With this in mind, our patient was maintained on azathioprine and on anti-TNF therapy. If corticosteroid treatment is deemed necessary, it should be kept to the minimum effective dosage and patients may be offered a statin, as there is some evidence that it decreases the incidence of osteonecrosis in patients receiving high-dose steroids[15]. Moreover, hyperlipidemia and diabetes should be treated and alcohol ingestion avoided.

In conclusion, although very rare, osteonecrosis is a devasting event that can occur in CD. As we demonstrate with this report, awareness of risk factors, such as corticosteroid therapy and inflammatory bowel disease activity, is crucial to make the diagnosis of this rheumatological IBD complication. Prompt treatment is recommended.

A 22 years old woman with active Crohn’s disease (CD) treated with prednisolone, messalazine, azathioprine and infliximab presented with bilateral knee pain exacerbated by movement, after an episode of bilateral septic arthritis of both knees.

On clinical examination, bilateral knee pain aggravated by movement and weight-bearing was observed.

Another causes of osteonecrosis were excluded, such as: Systemic lupus erythematosus (with or without antiphospholipid syndrome), as well as other connective-tissue diseases, hematological diseases (sickle cell disease, hemoglobinopathies), hyperlipidemia.

The peripheral blood smear was normal. Lipid levels (cholesterol and triglycerides) were within normal range. Antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antismooth muscle antibody and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. Procoagulant factors (C and S proteins, antithrombina III and V Leiden factor) were normal.

Plain film radiographies of the knees demonstrated multiple bilateral hypotransparent areas in the distal extremity of the femurs, in the proximal extremity of the tibiae and in the patellas and also absence of signs of subchondral collapse. Computed tomography revealed multiple lacunar areas in the same localizations. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a “geographic” pattern resulting from multiple osseous medullary infarcts in the distal 15 cm of the femurs, in the proximal 10 cm of the tibiae and in the patellas; there were also no signs of subchondral collapse. These imagiologic findings were consistent with the diagnosis of osteonecrosis.

Histological examination of both cortical bone and bone marrow was not performed because imagiological findings showed typical findings of osteonecrosis.

A conservative strategy was adopted. After an initial period of immobilization and restriction of weight-bearing with the use of crutches, the patient was started on a rehabilitation programme. The patient recovered completely and maintains therapy with azathioprine and messalazine.

There are few case reports in the literature of osteonecrosis in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The description of involvement of both knees is exceedingly rare.

All terms in this case report are standard and used in the field of gastroenterology.

Although very rare, osteonecrosis is a devasting event that can occur in CD. As they demonstrate with this report, awareness of risk factors, such as corticosteroid therapy and IBD activity, is crucial to make the diagnosis of this rheumatological IBD complication. Prompt treatment is recommended.

This case report demonstrates very well the occurrence of osteonecrosis in the setting of inflammatory.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Portugal

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Maric I S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Klingenstein G, Levy RN, Kornbluth A, Shah AK, Present DH. Inflammatory bowel disease related osteonecrosis: report of a large series with a review of the literature. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:94-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freeman HJ, Freeman KJ. Prevalence rates and an evaluation of reported risk factors for osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis) in Crohn’s disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hauzeur JP, Malaise M, Gangji V. Osteonecrosis in inflammatory bowel diseases: a review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2009;72:327-334. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Khan A, Illiffe G, Houston DS, Bernstein CN. Osteonecrosis in a patient with Crohn’s disease unrelated to corticosteroid use. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:765-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lanyi B, Dienes HP, Kruis W. [Recurrent aseptic osteonecrosis in Crohn’s disease - extraintestinal manifestation or steroid related complication?]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2005;130:1944-1947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kamata N, Oshitani N, Sogawa M, Yamagami H, Watanabe K, Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging for detection of asymptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on long-term corticosteroid treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:308-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hochberg M. Rheumatology. 4th edition. Londres. USA: Mosby Elsevier 2008; . |

| 9. | Madsen PV, Andersen G. Multifocal osteonecrosis related to steroid treatment in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:132-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, Guslandi M, Oldenburg B, Dotan I, Marteau P. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Malizos KN, Karantanas AH, Varitimidis SE, Dailiana ZH, Bargiotas K, Maris T. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: etiology, imaging and treatment. Eur J Radiol. 2007;63:16-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sakai T, Sugano N, Nishii T, Haraguchi K, Yoshikawa H, Ohzono K. Bone scintigraphy for osteonecrosis of the knee in patients with non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gardeniers JM. ARCO international classification of osteonecrosis. ARCO Newsletter. 1993;5:79-82. |

| 14. | Lai KA, Shen WJ, Yang CY, Shao CJ, Hsu JT, Lin RM. The use of alendronate to prevent early collapse of the femoral head in patients with nontraumatic osteonecrosis. A randomized clinical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2155-2159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pritchett JW. Statin therapy decreases the risk of osteonecrosis in patients receiving steroids. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;173-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |