Published online Aug 6, 2016. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.440

Peer-review started: March 14, 2016

First decision: April 5, 2016

Revised: April 17, 2016

Accepted: May 7, 2016

Article in press: May 9, 2016

Published online: August 6, 2016

Processing time: 141 Days and 11.1 Hours

AIM: To classify changes over time in causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) and to identify factors associated with changes in the incidence and characteristics of diverticular hemorrhage (DH).

METHODS: A total of 1803 patients underwent colonoscopy for overt LGIB at our hospital from 1995 to 2013. Patients were divided into an early group (EG, 1995-2006, n = 828) and a late group (LG, 2007-2013, n = 975), and specific diseases were compared between groups. In addition, antithrombotic drug (ATD) use and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use were compared between patients with and without DH.

RESULTS: Older patients (≥ 70 years old) and those with colonic DH were more frequent in LG than in EG (P < 0.01). Patients using ATDs as well as NSAIDs, male sex, obesity (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2), smoking, alcohol drinking, and arteriosclerotic diseases were more frequent in patients with DH than in those without.

CONCLUSION: Incidence of colonic DH seems to increase with aging of the population, and factors involved include use of ATDs and NSAIDs, male sex, obesity, smoking, alcohol drinking, and arteriosclerotic disease. These factors are of value in handling DH patients.

Core tip: Colonic diverticular hemorrhage (DH) is the most frequent cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A rapid increase in the incidence of colonic DH has been seen with the aging population. One reason is the widespread adoption of antithrombotic drugs (ATDs) since the early 2000s, based on guidelines to prevent ischemic heart disease and ischemic cerebrovascular disease. DH is more likely in patients who are older, are men, obesity, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or ATDs, and have hypertension and diabetes associated with arteriosclerotic disease. These factors are of value in handling DH patients.

- Citation: Kinjo K, Matsui T, Hisabe T, Ishihara H, Maki S, Chuman K, Koga A, Ohtsu K, Takatsu N, Hirai F, Yao K, Washio M. Increase in colonic diverticular hemorrhage and confounding factors. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7(3): 440-446

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v7/i3/440.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.440

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is often diagnosed in patients with overt bleeding, positive results for fecal occult blood, abdominal symptoms, and anemia. Colonoscopy is often the first test performed as an approach to the diagnosis and treatment of LGIB. In the United States, endoscopy is recommended “in the early evaluation of severe acute LGIB”[1].

Use of oral antithrombotic drugs (ATDs) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is increasing with the aging of the population, and the number of patients with diseases causing LGIB is increasing[2,3]. In addition, the types of diseases being encountered are also changing. In particular, the prevalence of colonic diverticulum is increasing. The aging population in Japan, as in Western countries, is showing an increase in diverticulosis[4,5]. DH is also increasing in Japan. In fact, diverticular hemorrhage (DH) is now one of the most common causes of LGIB in Japan and Western countries[2,3,6].

The present study examined changes over time in diseases causing LGIB that are associated with aging. In particular, this study sought to identify factors associated with changes in the incidence and patient characteristics of colonic DH.

Among 42540 patients who underwent colonoscopy at our hospital during the 19-year period between January 1995 and December 2013, this retrospective study included those who underwent colonoscopy for overt LGIB. Our hospital is one of the emergency hospitals in Chikushino city, Fukuoka, Japan.

Our hospital also diagnoses and treats a large number of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Patients with IBD (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Behçet’s disease, intestinal tuberculosis) were excluded because of differences from other diseases in terms of diagnosis and treatment. We also excluded patients who developed bleeding after endoscopic treatment (e.g., biopsy, polypectomy), or who experienced bleeding from the small bowel. As a result, this study included 1803 patients, all of whom were Japanese. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital (R15-024) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Also, since this was a retrospective study, the need to obtain informed consent to participate in the study was waived by the review board.

Factors evaluated included sex (male/female ratio) and age ≥ 70 years, Obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2]. Patients were categorized into 2 groups according to the use of oral ATDs [antiplatelet drugs (n = 266)]: Low-dose aspirin, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, cilostazol, limaprost alfadex, ethyl icosapentate, dipyridamole, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, beraprost sodium, dilazep; or anticoagulants (n = 58): Warfarin and dabigatran: No ATDs; ≥ 1 oral ATDs. Use of NSAIDs (loxoprofen, diclofenac, ibuprofen, etodolac, meloxicam, or celecoxib) was also examined. Two-group comparisons included the use or non-use of NSAIDs and the use or non-use of NSAIDs in combination with an antithrombotic drug.

Two-group comparisons for lifestyle factors included smoking or non-smoking and use or non-use of alcohol. We treated current and past smoking as positive for smoking, while only current drinkers were defined as positive for alcohol. Other factors examined other underlying diseases (cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, and chronic kidney disease). Comorbidity was quantified using the Charlson Risk Index (CRI)[7]. Two groups were compared: CRI ≤ 1; and CRI ≥ 2. Transfusion requiring ≥ 2 units of blood was also examined as a factor.

Colonoscopy was generally performed on the day of or the day after overt bleeding. Depending on the clinical symptoms and physical examination findings in each patient, colonoscopy was performed without pretreatment, or after pretreatment with an enema or bowel-cleansing agent. Olympus colonoscopes were used (PCF-240AZI, PCF-240AI, CF-240AZI, CF-240ZI, PCF-260AZI, PCF-PQ260I, and CF-260AI; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Colonic DH was defined as follows[8].

Definite colonic DH (n = 207): (1) Active bleeding observed from a diverticulum; and (2) Presence of blood clots, erosions, or an exposed vessel near a diverticulum.

Either (1) or (2), absence of blood in the terminal ileum on total colonoscopy, and no other obvious cause of bleeding.

Suspected colonic DH (n = 66): Obvious bloody stools, no blood in the terminal ileum on colonoscopy after bowel preparation, and the only likely cause of bleeding is DH.

Diseases causing LGIB were classified into hemorrhoids, ischemic colitis, DH, advanced colon cancer, early colon cancer/polyps/adenomas, infectious enteritis, angiodysplasia, drug-related enteritis, and no abnormal findings. Rectal ulcers, stercoral ulcers, rectal mucosal prolapse, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, enteric endometriosis, submucosal tumors, radiation enteritis, and nonspecific inflammation were categorized as “Others”.

The 1803 patients who underwent colonoscopy for overt LGIB were divided into two groups by time period, with each consisting of about half of the patients. The early group (EG, n = 828) was treated from January 1995 to December 2006, and the late group (LG, n = 975) was treated from January 2007 to December 2013. Incidence of each disease during these two periods was compared.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables between the two groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

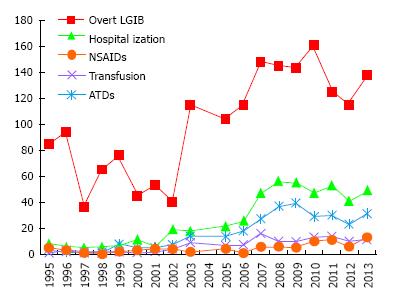

A total of 1803 patients underwent colonoscopy for overt LGIB at our hospital between 1995 and 2013. Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics. Figure 1 shows the number of patients who underwent colonoscopy for overt LGIB each year, required hospitalization, required transfusions, and used oral ATDs and NSAIDs. The number of patients with overt LGIB tended to increase each year.

| Age, sex and other factors | Overall n = 1803 n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 913 (50.6) |

| Female | 890 (49.4) |

| Age, yr | |

| Mean | 59.0 ± 18.6 |

| ≥ 70 | 582 (32.3) |

| < 70 | 1221 (67.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |

| < 18.5 | 212 (11.8) |

| 18.5 to < 25 | 1049 (58.2) |

| ≥ 25 | 337 (18.7) |

| Unknown | 205 (11.4) |

| Oral drugs | |

| ATDs | 308 (17.1) |

| NSAIDs | 115 (6.4) |

| ATDs + NSAIDs | 26 (1.4) |

| Lifestyle habits | |

| Smoking (current/past) | 551 (30.6) |

| Alcohol drinking (current) | 625 (34.7) |

| Underlying disease | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 171 (9.5) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 143 (7.9) |

| Hypertension | 658 (36.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 355 (19.7) |

| Hyperuricemia | 91 (5.0) |

| Diabetes | 207 (11.5) |

| Chronic liver disease | 106 (5.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 43 (2.4) |

| Charlson Risk Index | |

| ≤ 1 | 1413 (78.4) |

| ≥ 2 | 390 (21.6) |

| Blood transfusion | 130 (7.2) |

Table 2 summarizes the specific diseases in the 1803 patients who underwent colonoscopy for overt LGIB. In EG, the most common cause of overt LGIB was hemorrhoids in 212 patients (25.6%), followed by ischemic colitis in 143 patients (17.3%), advanced cancer in 80 patients (9.7%), early cancer/adenomas/polyps in 53 patients (6.4%), and colonic DH in 49 patients (5.9%). In LG, the most common cause of overt LGIB was colonic DH in 224 patients (23.0%), followed by hemorrhoids in 220 patients (22.6%), ischemic colitis in 173 patients (17.7%), advanced cancer in 73 patients (7.5%), and early cancer/adenomas/polyps in 58 patients (5.9%).

| Age, sex and cause/site of bleeding | All patients (1995-2013)n = 1803 | EG (1995-2006)n = 828 | LG (2007-2013)n = 975 | P-value | Adjusted P-value |

| Old age (≥ 70 yr) | 582 (32.3) | 196 (23.7) | 386 (39.6) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Male | 913 (50.6) | 419 (56.0) | 495 (50.8) | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| External/internal hemorrhoids | 432 (24.0) | 212 (25.6) | 220 (22.6) | 0.13 | 0.46 |

| Ischemic colitis | 316 (17.5) | 143 (17.3) | 173 (17.7) | 0.79 | 0.1 |

| Colonic DH | 273 (15.1) | 49 (5.9) | 224 (23.0) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Advanced colonic cancer | 153 (8.5) | 80 (9.7) | 73 (7.5) | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Early colon cancer/colon adenomas/polyps | 111 (6.2) | 53 (6.4) | 58 (5.9) | 0.69 | 0.73 |

| Infectious enteritis | 68 (3.8) | 37 (4.5) | 31 (3.2) | 0.15 | 0.4 |

| Angiodysplasia | 27 (1.5) | 15 (1.8) | 12 (1.2) | 0.31 | 0.26 |

| Drug-related enteritis | 23 (1.3) | 13 (1.6) | 10 (1.0) | 0.3 | 0.32 |

| Others | 248 (13.8) | 137 (16.5) | 111 (11.4) | - | - |

| No abnormal findings | 152 (8.4) | 89 (10.7) | 63 (6.5) | - | - |

| Total | 1803 (100) | 828 (100) | 975 (100) | - | - |

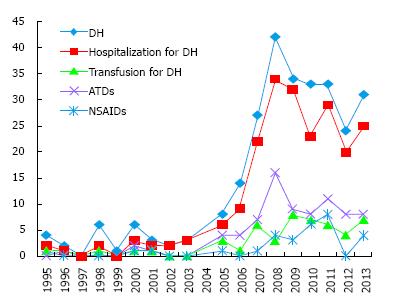

Compared with LG, EG showed lower frequencies of patients ≥ 70 years old (P < 0.01) and bleeding from colonic diverticulum (P < 0.01). The number of patients with DH tended to increase each year, with a marked increase after 2003 (Figure 2).

As shown in Table 3, compared with non-DH, DH showed higher frequencies of patients ≥ 70 years old (P < 0.01) and male patients (P < 0.01). Seventy-nine (28.9%) of the 273 DH patients and 229 (15.0%) of the 1530 non-DH patients received ATDs. ATDs were thus more commonly used in DH patients than in non-DH patients (P < 0.01). Thirty (11.0%) of the 273 DH patients and 85 (5.6%) of the 1530 non-DH patients took oral NSAIDs. Oral NSAIDs were thus also more commonly used in DH patients than in non-DH patients (P < 0.01).

| DH (n = 273) | Non-DH (n = 1530) | Adjusted P value | |

| Old age (≥ 70 yr) | 136 (49.8) | 446 (29.2) | < 0.01 |

| Male sex | 172 (63.0) | 741 (48.4) | < 0.01 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) | 82 (30.0) | 255 (16.7) | < 0.01 |

| ATDs | 79 (28.9) | 229 (15.0) | < 0.01 |

| NSAIDs | 30 (11.0) | 85 (5.6) | < 0.01 |

| Smoking (current/past) | 124 (45.4) | 427 (27.9) | < 0.01 |

| Alcohol drinking (current) | 139 (50.9) | 486 (31.8) | < 0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 36 (13.2) | 134 (8.8) | 0.67 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 34 (12.5) | 109 (7.1) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 178 (65.2) | 480 (31.4) | < 0.01 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 74 (27.1) | 281 (18.4) | < 0.05 |

| Hyperuricemia | 20 (7.3) | 71 (4.6) | 0.78 |

| Diabetes | 44 (16.1) | 163 (10.7) | < 0.01 |

| Chronic liver disease | 13 (4.8) | 93 (6.1) | 0.1 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (2.9) | 35 (2.3) | 0.94 |

| Charlson Risk Index ≥ 2 | 79 (28.9) | 311 (20.3) | 0.67 |

| Blood transfusion | 56 (20.5) | 74 (4.8) | < 0.01 |

In addition, obesity (P < 0.01), smoking (P < 0.01), alcohol drinking (P < 0.01), hypertension (P < 0.01), hyperlipidemia (P = 0.02), diabetes (P < 0.01), and requirement for blood transfusion (P < 0.01) were significantly more frequent in DH patients than in non-DH patients.

The incidence of LGIB increased from 20.5/100000 inhabitants/year in the early 1990s[6] to 87/100000 inhabitants/year in 2010[3]. In particular, the incidence of LGIB is high in elderly patients (690/100000 inhabitants/year)[3], and is expected to continue increasing with the aging of the population in Japan. The aging rate (≥ 65 years old) of Japan was 12% in 1990, 20% in 2005. However, the aging rate of 2013 is higher than 25%, and aging advances[9]. Our study also showed an annual increase in the number of patients undergoing colonoscopy for overt LGIB. One background factor was the approval of low-dose aspirin 100 mg in Japan as an antiplatelet drug in 2000, with initial marketing in 2001. In addition, ATDs such as clopidogrel and warfarin became more widely used for risk reduction and secondary prevention of cerebral and cardiovascular events in Japan, based on 2002-2009 guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association[10,11]. ATDs and NSAIDs have been reported as risk factors for LGIB[2,3]. These background factors, together with the aging of the population, are thought to be key reasons for the rapid increase in the incidence of LGIB.

In particular, the incidence of colonic DH increased markedly from 5.9% in EG to 23.0% in LG, with a pronounced change in the specific diseases causing LGIB. In LG, colonic DH was the most common disorder causing LGIB. Moreover, colonic DH has also recently been reported as the most common cause of LGIB in Japan[2,12]. Compared to a few decades ago, changes in the aging-associated diseases that cause LGIB have been occurring. In particular, the incidence of colonic DH has increased.

Colonic diverticulosis itself is increasing. During the period from 1960 to the 1980s, Kubo et al[13] reported that the prevalence of colonic diverticula was only 8.9% among patients who underwent barium enema examination. Since the 1990s, the prevalence of diverticulosis seen on barium enema examination or colonoscopy has increased to 15%-25%[5,14]. In addition, more than 80% of patients who had diverticulosis were elderly. Diverticulosis is thus thought to increase with aging[5]. As the absolute number of diverticula in colonic diverticulosis increases with the aging of the population, the risk of DH is increased. Moreover, as mentioned previously, the availability of low-dose aspirin has probably also contributed to the rapid rise in DH starting in 2001.

Of course, bleeding does not occur in all patients with diverticulosis. In fact, bleeding only occurs in 2%-5% of patients during the natural history of diverticulosis, and most cases are relatively mild, resolving spontaneously in 75%-93% of cases[15,16].

In a case-control study in Japan, risk factors for DH included the use of ATDs and NSAIDs, hypertension, diabetes, arteriosclerotic diseases such as ischemic disease mellitus and chronic kidney disease, age ≥ 70 years, obesity[13,15,17,18]. Our study also found higher rates of use for both ATDs and NSAIDs, higher age and male sex, obesity, smoking, alcohol drinking, and arteriosclerotic diseases in patients with colonic DH compared to those with bleeding from other causes. ATDs and NSAIDs thus represent risk factors for bleeding in diverticulosis. Moreover, higher rates of DH in patients who are older, obesity, smoke, or drink alcohol may be related to the association between older age, obesity, smoking, and alcohol drinking with arteriosclerotic disease.

Colonic diverticula develop at sites where the vasa recta penetrate the large intestinal wall when intestinal pressure increases. Blood vessels in the diverticula are separated from the bowel lumen only by the mucosa, and are easily injured. With repeated mechanical stimuli, intimal thickening of the vasa recta occurs, often with thinning of the media. These changes can cause segmental weakening of the vasa recta, which may lead to arterial hemorrhage in the bowel lumen[19]. Thus, because DH represents a form of arterial bleeding, transfusion may be required more often than with bleeding due to other disorders.

Arteriosclerosis also plays a role in the pathogenesis leading to rupture of blood vessels in diverticula[20]. However, not all patients with diverticulosis experience bleeding; indeed, most patients remain asymptomatic. Therefore, in addition to arteriosclerosis, other factors increase the fragility of blood vessels in diverticula.

Our study was performed with adjustment for factors including sex and age, so analysis was performed independently of arteriosclerosis. The results identified NSAIDs and ATDs as a significant risk factor, suggesting that NSAIDs and ATDs have synergistic effects on injury to blood vessels in diverticula. Most NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which disrupts the microcirculation and inhibits platelet aggregation. As a result, NSAIDs can lead to bleeding in patients with diverticulosis[17]. DH in Japan is more common in men, whereas in Western countries, DH occurs equally in men and women[21]. These findings suggest ethnic differences, but the exact factors involved are not yet well understood. DH in Japan is more common in men, because it may be one of the reasons the men listed as the risk of arteriosclerosis in the Japan Atherosclerosis Society Guidelines[22].

Our study examined patients who underwent colonoscopy for LGIB over a 19-year period, including detailed information about underlying diseases and medications, and found an increase in overt LGIB during this time. The investigation included a relatively large cohort of 273 patients with colonic DH for comparison and analysis. We compared the baseline data of DH patients and those of non-DH patients among all subjects in this cohort. Therefore, there may have been little recall bias or selection bias in our study. We divided it in 2004 when we divided it for the same period or in 2000 when low-dose aspirin was approved as division of EG and LG. However, number of cases included a difference too much in EG and LG and was inappropriate for analysis. Thus, the 1803 patients were divided into two groups by time period, with each consisting of about half of the patients.

However, some limitations to the study must be considered. One was the retrospective nature of the study design, and the fact that only a single institution was involved. In addition, this was not a strictly controlled study, as no comparison with non-bleeding diverticulosis was conducted. We had not evaluated by carotid artery ultrasonography for arteriosclerosis in this study.

In conclusion, a rapid increase in the incidence of colonic DH has been seen with the aging population. One reason is the widespread adoption of ATDs since the early 2000s, based on guidelines to prevent ischemic heart disease and ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Colonic DH is the most frequent cause of LGIB.

DH is more likely in patients who are older, are men, obesity, use NSAIDs or ATDs, and have hypertension and diabetes associated with arteriosclerotic disease. These patients are also likely to have more severe anemia and require blood transfusions. These factors should be kept in mind when treating patients with LGIB.

We thank Mr. Matt Morgan Forte Inc for assistance with the translation to English.

With the aging of the population in Japan, dramatic changes in the incidence of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) have been seen, particularly as an increase in colonic diverticular hemorrhage.

Colonic diverticular hemorrhage (DH) is more likely in patients who are older, are men, obesity, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or antithrombotic drugs (ATDs), and have hypertension and diabetes associated with arteriosclerotic disease.

Older patients and those with colonic DH were more frequent in late group than in early group (P < 0.01). Patients using ATDs as well as NSAIDs, male sex, obesity, smoking, alcohol drinking, and arteriosclerotic diseases were more frequent in patients with DH than in those without.

Incidence of colonic DH seems to increase with aging of the population, and factors involved include use of ATDs and NSAIDs, male sex, obesity, smoking, alcohol drinking, and arteriosclerotic disease. These factors should be kept in mind when treating patients with LGIB.

NSAIDs and ATDs have synergistic effects on injury to blood vessels in diverticula. Most NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which disrupts the microcirculation and inhibits platelet aggregation. As a result, NSAIDs can lead to bleeding in patients with diverticulosis, including severe DH.

This is an interesting manuscript which analyses the spectrum of LGIB in a single center retrospective analysis at Fukuoka University Hospital in chikushino city in Japan, and provides further data on the incidence and risk factors for colonic DH. Amongst a total of 1803 japanese patients with LGIB with a mean age of 59 years, 273 patients with colonic DH were separated into an early (1995-2006) and late (2007-2013) group.

Manuscript Source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Japan

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Liu DL, Ozuner G, Reichert MC, Wani HU S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Davila RE, Rajan E, Adler DG, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Qureshi W, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the patient with lower-GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:656-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, Shimbo T, Kishida Y, Sekine K, Tanaka S, Okubo H, Watanabe K, Sakurai T. Lower GI bleeding risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antiplatelet drug use alone and the effect of combined therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:1124-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hreinsson JP, Gumundsson S, Kalaitzakis E, Björnsson ES. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology, and outcomes in a population-based setting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Nakaji S, Sugawara K, Saito D, Yoshioka Y, MacAuley D, Bradley T, Kernohan G, Baxter D. Trends in dietary fiber intake in Japan over the last century. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, Shimbo T, Itoh T, Goda Y, Suda R, Yano H, Akiyama J, Yanase M. Increase in colonic diverticulosis and diverticular hemorrhage in an aging society: lessons from a 9-year colonoscopic study of 28,192 patients in Japan. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:379-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:419-424. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, Kovacs TO. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Population prediction. [accessed 2015 Jan 14]. Available from: http://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/ja/h25/html/nc123110.html.. |

| 10. | Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4959] [Cited by in RCA: 4591] [Article Influence: 199.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Executive Summary. Circulation. 2006;114:700-752. |

| 12. | Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Kondo S, Ohta M, Watabe H, Maeda S, Togo G, Yamaji Y, Ogura K, Okamoto M. Assessment of the risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kubo A, Kagaya T, Nakagawa H. Studies on complications of diverticular disease of the colon. Jpn J Med. 1985;24:39-43. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nakada I, Ubukata H, Goto Y, Watanabe Y, Sato S, Tabuchi T, Soma T, Umeda K. Diverticular disease of colon at a regional general hospital in Japan. Dis colon Rectum. 1995;38:755-9 [PMID 7607039]. |

| 15. | Niikura R, Nagata N, Shimbo T, Aoki T, Yamada A, Hirata Y, Sekine K, Okubo H, Watanabe K, Sakurai T. Natural history of bleeding risk in colonic diverticulosis patients: a long-term colonoscopy-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:888-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McGuire HH. Bleeding colonic diverticula. A reappraisal of natural history and management. Ann Surg. 1994;220:653-656. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Willett WC. Use of acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a prospective study and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:255-260. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Nagata N, Sakamoto K, Arai T, Niikura R, Shimbo T, Shinozaki M, Aoki T, Sekine K, Okubo H, Watanabe K. Visceral fat accumulation affects risk of colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1399-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Meyers MA, Alonso DR, Baer JW. Pathogenesis of massively bleeding colonic diverticulosis: new observations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:901-908. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chen CY, Wu CC, Jao SW, Pai L, Hsiao CW. Colonic diverticular bleeding with comorbid diseases may need elective colectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stollman N, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. Lancet. 2004;363:631-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Japan Atherosclerosis Society. [Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases]. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2007;4:5-57. [PubMed] |