Published online May 6, 2016. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i2.274

Peer-review started: October 29, 2015

First decision: December 11, 2015

Revised: December 23, 2015

Accepted: January 9, 2016

Article in press: January 13, 2016

Published online: May 6, 2016

Processing time: 176 Days and 5.7 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 in subjects with self-reported occasional constipation.

METHODS: Eligible subjects ≥ 17 years of age were randomized to receive either placebo or PEG 3350 17 g once daily in this multicenter, double-blind trial. Evaluations were conducted before (baseline) and after a 7-d treatment period. The primary efficacy variable was the proportion of subjects reporting complete resolution of straining and hard or lumpy stools. Secondary efficacy variables assessed the severity of the subjects’ daily bowel movement (BM) symptoms, and preference of laxatives based on diary entries, visual analog scale scores, and questionnaires.

RESULTS: Of the 203 subjects enrolled in the study, 11 had major protocol violations. Complete resolution was noted by 36/98 (36.7%) subjects in the PEG 3350 group and 23/94 (24.5%) in the placebo group (P = 0.0595). The number of complete BMs without straining or lumpy stools was similar between both groups. Subjects receiving PEG 3350 experienced significant relief in straining and reduction in hardness of stools over a 7-d period (P < 0.0001). Subjects reported that PEG 3350 had a better effect on their daily lives, provided better control over a BM, better relief from constipation, cramping, and bloating, and was their preferred laxative. Adverse events (AEs) were balanced between the PEG 3350 and the placebo groups. No deaths, serious AEs, or discontinuations due to AEs were reported. This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00770432.

CONCLUSION: Oral administration of 17 g PEG 3350 once daily for a week is effective, safe, and well tolerated in subjects with occasional constipation.

Core tip: Unlike chronic constipation, which typically needs to be diagnosed by a healthcare professional, occasional constipation is a self-diagnosed condition. polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 (MiraLAX®) is a Food and Drug Administration-approved, once-daily oral over-the-counter laxative indicated for short-term (1 wk) use to relieve occasional constipation. However, very few data are available on the effectiveness of PEG 3350 for the treatment of occasional constipation. This is the first placebo-controlled study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of PEG 3350 in subjects with occasional constipation after a week’s treatment.

- Citation: McGraw T. Polyethylene glycol 3350 in occasional constipation: A one-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7(2): 274-282

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v7/i2/274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i2.274

Constipation is a common disorder that affects people of all ages and both sexes, with a predilection for the elderly and female populations[1-3]. Constipation negatively impacts quality of life (QoL), with a magnitude that is comparable to that in patients with chronic allergies, dermatitis, diabetes, and stable ulcerative colitis[4,5].

There is a high level of discrepancy in the diagnosis of constipation between patients and healthcare practitioners. Consequently, the prevalence of constipation differs based on the definition of constipation used. In adults, constipation as defined strictly on the basis of frequency of bowel movements (BMs), such as having a BM fewer than three times a week[6], accounts for a prevalence rate ranging from < 1% to 5.4%[7]. Higher prevalence rates are observed when constipation is self-reported or includes symptoms of constipation such as straining, hard and lumpy stools, bloating, and infrequent defecation[8-10]. The rome III criteria were devised to facilitate a diagnosis of functional constipation, accommodating both frequency of BMs and symptoms of constipation[11]. Results from surveys suggest that the prevalence of constipation perceived by patients is generally higher than that based on Rome criteria-diagnoses[12]. Only 50% of self-reported constipation fulfills the Rome criteria[13]. Constipation represents varying complaints among individuals that often cannot be restricted to frequency and/or two or more symptoms. Thus, a comprehensive definition of constipation needs to account for the patient’s perception.

Constipation may persist for 3 mo or more, as in chronic constipation, or may be intermittent, lasting for shorter periods of time before resolving spontaneously as seen in occasional constipation. Unlike chronic constipation, which typically needs to be diagnosed by a healthcare professional, occasional constipation is a self-diagnosed condition that is often relieved by lifestyle changes or over-the-counter (OTC) laxatives[14]. Although there is no validated, agreed-upon definition of occasional constipation, this study evaluated occasional constipation sufferers as being those with constipation (straining with lumpy or hard stools, or the inability to produce a BM in the last 48 h) that does not resolve on its own with time, as opposed to chronic sufferers who need prescription medication and/or medical intervention to resolve their problem. Laxatives with an osmotic effect, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and lactulose, are common OTC treatments for constipation[15-17]. Osmotic laxatives aid defecation by increasing the osmotic pressure in the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract. Osmotic laxatives are known to improve frequency, straining, and the form of stools[17-19]. PEG has been shown to be more effective than lactulose in the management of chronic constipation and exhibited lesser side effects than lactulose[15,16]. PEG is a non-absorbable and non-metabolizable polymer that is not fermented by the gut flora and hence does not contribute to gas accumulation[20].

MiraLAX® is PEG 3350 powder, without any excipients, that retains water in the intestinal lumen by forming hydrogen bonds with water[21], resulting in softening of the stools. PEG 3350 is effective in the treatment of constipation in adults, having been shown to significantly increase the frequency of BMs, improve the symptoms of constipation[22-26], and reduce cramping and gas[19]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved PEG 3350 (MiraLAX®) on October 6, 2006 (NDA 22-015) for use as a nonprescription laxative for relief from occasional constipation (irregularity). However, efficacy and safety trials of PEG 3350 for the treatment of constipation were conducted in subjects with chronic constipation that generally fulfilled the Rome II criteria for constipation, which requires subjects to present symptoms of constipation for at least 12 wk, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 mo.

This study investigated the efficacy, safety, and preference for PEG 3350 based on the current marketed dose in subjects who occasionally used OTC laxatives.

This study was a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study; Protocol # CL2007-12; Clinicaltrials.gov registration: NCT00770432. The study complied with US Code of Federal Regulations title 21, parts 50 and 56 for informed subject consent and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. The study was reviewed and supervised by Allendale IRB for all sites.

The study comprised two visits: One prior to, and one following, a 7-d at-home double-blind treatment period. Subjects were provided the investigational medications, instructed on study procedures, and required to complete questionnaires on symptoms, QoL, global evaluation, and preference during the visits. Each subject’s participation lasted up to 13 d.

Key inclusion criteria for the study required subjects to be ≥ 17 years of age with a current diagnosis of untreated constipation for ≤ 7 d based on signs/symptoms of straining and hard or lumpy stools or inability to have a BM within 48 h prior to randomization of the trial. Subjects were required to demonstrate their willingness to participate by signing a written informed consent. Subjects had to be users of OTC laxatives for the treatment of occasional constipation (defined as using a nonprescription laxative to treat < 3 episodes of constipation within the last 12 mo prior to randomization). Subjects were required not to use any medication to either treat the constipation or known to cause constipation during the course of the study. Subjects were in otherwise good health as determined by physical examination and medical history. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had a history of chronic constipation or were in the midst of having a constipation episode lasting for more than 1 wk prior to randomization or were under doctor’s care for constipation at the time of study. Subjects who previously used PEG as a laxative; subjects with severe abdominal pain as their predominant complaint; subjects who participated in an investigational clinical surgical, drug, or device study within 30 d prior to randomization; subjects who were allergic to PEG or maltodextrin; and subjects with a history of alcohol or drug abuse were also excluded from the study.

Subjects who fulfilled the enrollment criteria were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive PEG 3350 or placebo according to a computer-generated randomization code. Subjects were randomly assigned the investigational drug or placebo at each site by selection of the next box of medication in the numerical sequence from the shipment provided. Maltrin® M500 (maltodextrin 500) that was identical in appearance and taste to PEG 3350 was used as the placebo and was dispensed in identical bottles as PEG 3350.

PEG 3350 17 g or a similarly sized dose of placebo (maltodextrin 500) was mixed in 4-8 ounces of any hot, cold, or room temperature beverage and was administered orally for a 7-d period. Per protocol, dosage was once (prior to noon) at approximately the same time each day. Subjects were instructed to return all test articles for inventory and accountability.

Treatment compliance was based on completion of at least 5 of 7 diary days with answers to questions regarding study drug dosing and primary endpoints. Each subject indicated in the daily diary whether or not a complete or incomplete BM was accompanied by straining and whether the stool was hard or lumpy.

The primary efficacy variable assessed the proportion of subjects who self-reported complete resolution of straining and hard/lumpy stools for the intent-to-treat (ITT) and the per-protocol (PP) populations. Complete resolution was defined by daily diary reports of a complete BM with no straining or hard/lumpy stools for at least 48 h without a recurrence of ≥ 2 consecutive BM episodes with straining or hard/lumpy stools. Secondary endpoints included diary ratings of visual analog scale (VAS) format (BM control, gas bloating, abdominal discomfort/cramping, and well-being) and binary outcomes (BM satisfaction and BM sense of completion). Response to treatment based on laxative preference (Likert scale and VAS) was assessed.

The safety endpoint was based on tabulation and analysis of adverse events (AEs) and measurement of vital signs at the first visit.

The ITT population received at least one dose of the assigned drug and underwent a baseline and post-baseline evaluation performed at the visits. The PP population included all ITT subjects who additionally had no major protocol violations or other events biasing their study outcome (e.g., use of prohibited medications or excessive missing data).

The safety population included all subjects that took one or more dose of study medication, and was equivalent in numbers to the ITT populations.

Detection of a 25% difference in a binomial endpoint (P = 0.05), which may be considered clinically significant, required a sample size of 85 per group for 90% power. Allowing for a 15% rate of early discontinuation, a sample of 196 subjects was estimated to complete with 170 subjects.

Statistical analysis was performed for the primary efficacy variable on the ITT and PP populations between the two treatment groups using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) analysis adjusting for investigational site. VAS and Likert ratings were analyzed between the treatment groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors for treatment, site, and treatment-site interaction. The VAS rating scales were assessed as percent change from baseline over time. Preference questionnaires were presented as binary outcomes and analyzed using CMH and ANOVA.

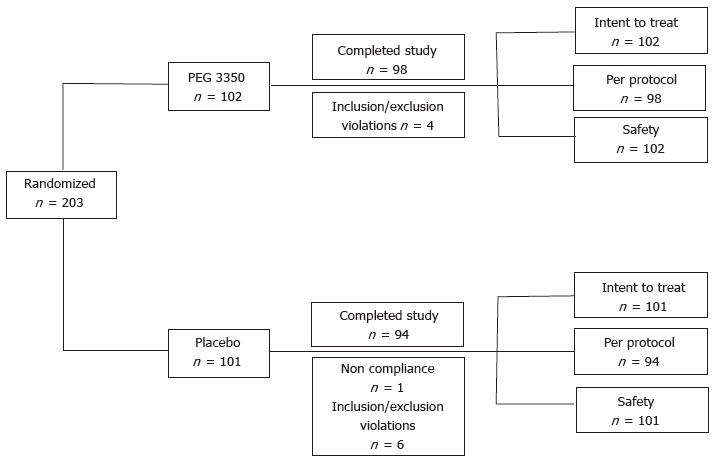

A total of 203 subjects - 102 in the PEG 3350 group and 101 in the placebo group - from 7 investigational sites were enrolled in the study from November 28, 2007, with the last subject’s visit on January 18, 2008. The study was completed by 98 subjects (96.1%) in the PEG 3350 group and 94 subjects (93.1%) in the placebo group (Figure 1). A total of 11 subjects (7 in the placebo group and 4 in the PEG 3350 group) had major protocol violations prior to breaking of the randomization code, and were excluded from the PP group analysis. All randomized subjects were enrolled in the ITT population (i.e., subjects who received at least one dose of the assigned drug and had a baseline and post-baseline evaluation performed at the visits). Subjects’ ages ranged between 17 and 79 years. Approximately three quarters of subjects were White, and 71% were female (29% male) (Table 1). Subjects in both treatment groups were well matched with regards to medical history, baseline physical examinations, vital signs, and other baseline characteristics (Table 1). Similar percentages of treatment compliance were observed for both the treatment groups; 99% for the PEG 3350 group and 98% for the placebo group. Because only 11 (5.4%) subjects of the ITT population were not part of the PP population, the results are presented for the PP population to assess the robustness of the study.

| Summary | Treatment group | All subjects | P value1 | |

| PEG 3350 | Placebo | |||

| ITT subjects | 102 | 101 | 203 | |

| Gender | 0.2165 | |||

| Male | 25 (24.5) | 33 (32.7) | 58 (28.6) | |

| Female | 77 (75.5) | 68 (67.3) | 145 (71.4) | |

| Age (yr) | 0.7361 | |||

| n | 102 | 101 | 203 | |

| Mean ± SD | 45.8 ± 12.52 | 45 ± 14.15 | 45.4 ± 13.33 | |

| Race | 0.3340 | |||

| American Indian | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Alaskan native | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Black/African American | 7 (6.9) | 9 (8.9) | 16 (7.9) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| White | 81 (79.4) | 71 (70.3) | 152 (74.9) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (13.7) | 19 (18.8) | 33 (16.3) | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.5257 | |||

| n | 102 | 101 | 203 | |

| Mean ± SD | 80.2 ± 19.11 | 79.7 ± 21.19 | 79.9 ± 20.12 | |

| On average, how many successful bowel movements does the subject have per week? | 0.8232 | |||

| 0-2 | 36 (35.3) | 35 (34.7) | 71 (35.0) | |

| 3-5 | 44 (43.1) | 40 (39.6) | 84 (41.4) | |

| 6-8 | 22 (21.6) | 25 (24.8) | 47 (23.2) | |

| > 9 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| What type of laxative is this? | 0.6775 | |||

| Stimulant | 57 (55.9) | 63 (62.4) | 120 (59.1) | |

| Bulk forming fiber | 12 (11.8) | 15 (14.9) | 27 (13.3) | |

| Lubricant | 3 (2.9) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Osmotic | 8 (7.8) | 4 (4.0) | 12 (5.9) | |

| Carbon dioxide releasing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Stool softener | 18 (17.6) | 15 (14.9) | 33 (16.3) | |

| Combination | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | |

| Other | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (2.0) | |

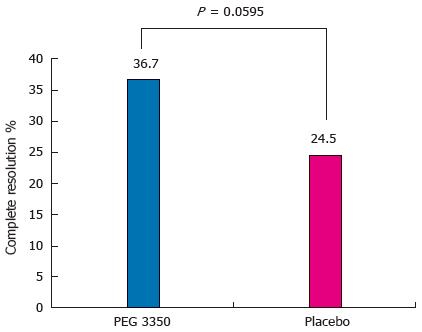

Analysis of the primary efficacy variable showed that in the PP population, 36 subjects (36.7%) on PEG 3350 reported complete resolution compared with 23 (24.5%) receiving placebo (P = 0.0595) (Figure 2).

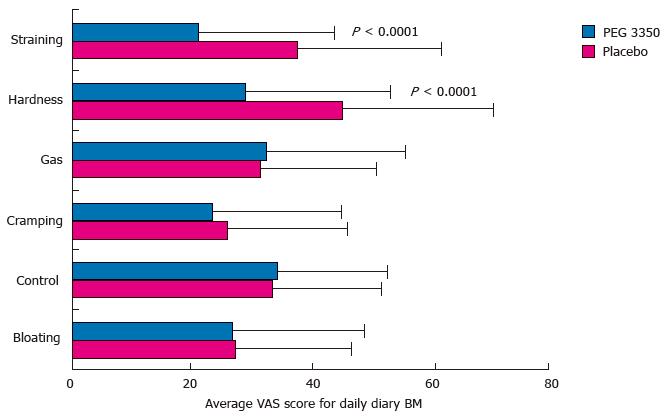

Secondary efficacy analysis showed statistically significant superiority of PEG 3350 over placebo. Subjects using PEG 3350 experienced significant relief in straining and reduction in the hardness of stools over the 7-d treatment period (P < 0.0001). Figure 3 shows that subjects using PEG 3350 recorded a VAS score of 29.0 vs 45.3 with placebo, for symptoms of hardness, and 21.1 vs 37.8, respectively, for straining. The percentage of all BMs that was complete without straining or lumpy stools was also significantly higher for the PEG 3350 group; 34% for PEG 3350 compared to 18.4% for the placebo group (P < 0.0002) (Table 2).

| Mean (SD) | Placebon = 94 | PEG 3350n = 98 | P value1 |

| Average BMs per day | 1.0 (0.63) | 1.1 (0.84) | 0.46 |

| Average BMs per day that were complete without straining or lumpy stool | 0.5 (0.46) | 0.6 (0.46) | 0.57 |

| Percent of all BMs that were complete without straining or lumpy stool | 18.4 (25.00) | 34 (35.84) | 0.0002 |

| Percent of all BMs that were failures | 10.2 (17.64) | 10.1 (19.31) | 0.94 |

| Percent of all BMs that were incomplete | 34.6 (27.75) | 25.7 (28.49) | 0.16 |

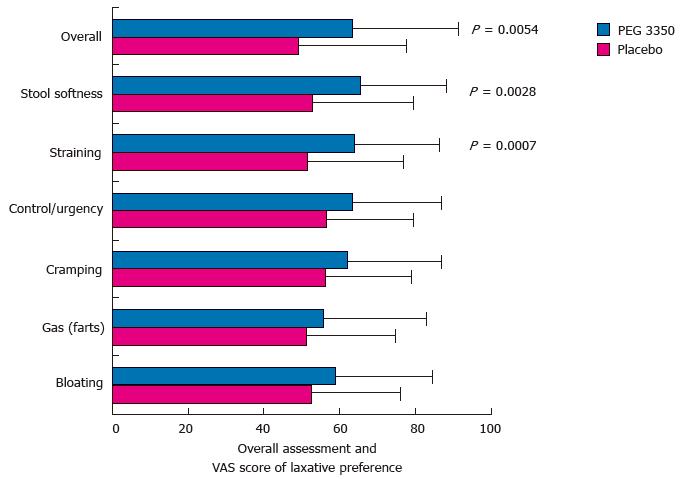

No statistical significance was observed for the number of complete BMs without straining or lumpy stools (Table 2). There was no significant decrease in the symptoms of constipation (bloating, gas, control, and cramping) with PEG 3350 over placebo, indicating that PEG 3350 did not improve or alleviate these symptoms (Figure 3). Global assessment of the effect of constipation on their daily lives showed that subjects randomized to PEG 3350 perceived a significantly better impact on their daily lives than did those randomized to placebo in all categories tested, and over 40% (ratio, 2:1) of subjects considered PEG 3350 to be the best laxative they had tried (Table 3). PEG 3350 was preferred over their usual laxative based on VAS rating, and when subjects were queried on the following: Recommendation (P = 0.0069), better relief from constipation (P = 0.0206), better relief from cramping (P = 0.0112), better relief from bloating

| Summary | Treatment group | P value1 | |

| PEG 3350 | Placebo | ||

| Per-protocol subjects, n | 98 | 94 | |

| It works better than other laxatives I have tried | |||

| Strongly agree | 16 (16.3) | 8 (8.5) | 0.0037 |

| Agree | 34 (34.7) | 27 (28.7) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24 (24.5) | 15 (16.0) | |

| Disagree | 19 (19.4) | 35 (37.2) | |

| Strongly disagree | 5 (5.1) | 9 (9.6) | |

| Not applicable/missing | 0 | 0 | |

| It is the best laxative I have tried | |||

| Strongly agree | 18 (18.4) | 7 (7.4) | 0.0005 |

| Agree | 22 (22.4) | 13 (13.8) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 26 (26.5) | 22 (23.4) | |

| Disagree | 23 (23.5) | 36 (38.3) | |

| Strongly disagree | 9 (9.2) | 16 (17.0) | |

| Not applicable/missing | 0 | 0 | |

| It helps me feel less irritable | |||

| Strongly agree | 6 (6.1) | 7 (7.4) | 0.0414 |

| Agree | 32 (32.7) | 26 (27.7) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 (38.8) | 25 (26.6) | |

| Disagree | 18 (18.4) | 21 (22.3) | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (4.1) | 14 (14.9) | |

| Not applicable/missing | 0 | 1 (1.1) | |

| It helps me feel more confident | |||

| Strongly agree | 7 (7.1) | 7 (7.4) | 0.0262 |

| Agree | 25 (25.5) | 15 (16.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 (38.8) | 28 (29.8) | |

| Disagree | 19 (19.4) | 28 (29.8) | |

| Strongly disagree | 8 (8.2) | 14 (14.9) | |

| Not applicable/missing | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.1) | |

| It feels better for my body than other laxatives I have tried | |||

| Strongly agree | 13 (13.3) | 8 (8.5) | 0.0215 |

| Agree | 34 (34.7) | 27 (28.7) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24 (24.5) | 15 (16.0) | |

| Disagree | 18 (18.4) | 30 (31.9) | |

| Strongly disagree | 9 (9.2) | 14 (14.9) | |

| Not applicable/ missing | 0 | 0 | |

(P = 0.0002), and better control over a BM (P = 0.0349) using the Likert scale (Figure 4).

The most frequently observed AEs included headache and back and neck pain and were similar for both treatment groups, indicating that this was not a drug-related effect (Table 4). No deaths or serious AEs were recorded from the therapy, and there were no discontinuations due to a drug-related AE.

| Summary | Treatment group | |

| PEG 3350 | Placebo | |

| Total subjects | 102 | 101 |

| Total subjects with an adverse event | 14 (13.7) | 17 (16.8) |

| Nervous system disorders | 11 (10.8) | 11 (10.9) |

| Headache | 11 (10.8) | 11 (10.9) |

| Migraine | 1 (< 1.0) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 3 (2.9) | 2 (2.0) |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| Neck pain | 2 (2.0) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 1 (< 1.0) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 4 (4.0) |

| Nausea | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 1 (< 1.0) |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 1 (< 1.0) |

| Infections and infestations | 1 (< 1.0) | 1 (< 1.0) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (< 1.0) | 0 |

| Sinusitis | 0 | 1 (< 1.0) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 (< 1.0) | 1 (< 1.0) |

| Insomnia | 1 (< 1.0) | 1 (< 1.0) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 2 (2.0) | 0 |

| Nasal congestion | 1 (< 1.0) | 0 |

| Pharyngolaryngeal pain | 1 (< 1.0) | 0 |

PEG 3350 (MiraLAX®) is an FDA-approved, once-daily, oral OTC laxative indicated for short-term (1 wk) use to relieve occasional constipation/irregularity. Subjects and healthcare practitioners have a wide range of treatment options for relieving symptoms of constipation. Large-scale randomized trials support lactulose[27,28], tegaserod[29], prucalopride, lubiprostone, and linaclotide[30], as well as PEG[19,22-25] for the treatment of chronic constipation. However, there are no reports on the effectiveness of PEG 3350 for the treatment of occasional constipation. This is the first placebo-controlled study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of PEG 3350 in subjects with occasional constipation after a week’s treatment. The current study demonstrated that in subjects with self-reported occasional constipation, there is no significant difference between PEG 3350 and placebo in achieving relief from straining and reduction in hardness of stools experienced during BMs. PEG 3350 was generally well tolerated; AEs were similar in incidence and severity (mostly mild) between treatment groups, in line with previous reports[19,22-26].

The present study used the subject’s own estimation of treatment effect to evaluate whether treatment with PEG 3350 led to resolution of straining and lumpy/hard stools compared with placebo. Although subjects on PEG 3350 had more successful BMs than did those on placebo during the treatment period, a statistically significant difference between PEG 3350 and placebo was achieved only on day 3 of treatment. In subjects receiving placebo, constipation resolved by day 5 as expected in occasional constipation, which may have resulted in a loss of significance between treatment arms. In the study of PEG 3350[25] for the treatment of chronic constipation, PEG 3350 was successful in treating constipation, where success was defined as a subject experiencing ≥ 3 satisfactory BMs per week and having no more than one of the remaining three Rome III symptoms. The same study also reported that PEG-treated subjects had higher incidences of complete spontaneous BMs over placebo[25]. In the present study, PEG 3350 was better, but not significantly different (P = 0.595) than placebo in producing a complete BM devoid of straining and hard/lumpy stools. However, significant results were obtained in favor of PEG 3350 with secondary measures that assessed subjective symptoms such as straining and hardness of stools. Because most subjects describe constipation as hard and lumpy stools and/or straining, the results of the study are clinically meaningful, despite the lack of statistical significance for the primary endpoint.

Most subjects suffering from constipation are likely, at least initially, to use OTC laxatives for relieving their symptoms, and are generally not satisfied with the results[3,7,31]. PEG 3350 has been reported to be effective in relieving cramping and gas symptoms in subjects with chronic constipation[19,26], yet other secondary measures evaluating the effect of PEG 3350 on cramping and gas showed no significant difference between PEG 3350 and placebo. This may be due to the fact that the beneficial effect of PEG relative to placebo is confined to improved stool consistency, which may be due to increased osmotic action of intraluminal content, and hence does not affect cramping and gas; it may also be due to the relatively milder symptoms of subjects with occasional constipation and the limited duration of treatment. The latter explanation is supported by the DiPalma study[19], which evaluated PEG 3350 in subjects with chronic constipation, and reported significantly less gas and cramping with PEG 3350. However, it should also be noted that the current study evaluated subjects with occasional constipation, a self-limiting condition, unlike the DiPalma study which evaluated patients with chronic constipation and who were enrolled strictly on the basis of stool frequency, i.e., ≤ 2 stools during the week and were treated with PEG for 2 wk. While it is plausible that significant differences in cramping and gas may be detected in the second week of treatment with PEG 3350, other long-term studies[22,23] have indicated no significant effect of PEG 3350 on flatulence, consistent with results of the present study.

Lifestyle modifications, diet, and defecation practices were not evaluated in the study. Lifestyle modifications and dietary fiber may help resolve occasional constipation symptoms, and bulk/roughage in the diet could have been measured to determine if these factors had an effect on the outcome. Also, bad defecation practices such as deferring the urge to defecate could have been monitored to determine if they affected or led to constipation. However, it is unlikely that these factors could have influenced the results of the study as the effects would be expected to be evenly distributed between the groups.

This study has important limitations. The sample size was estimated based on studies[22] conducted in subjects with chronic constipation, which showed an 11% success for subjects in the placebo group. The current study design used a primary endpoint in the first week of treatment that had not been previously reported, and hence there were very little clinical data available upon which to base sample size calculations. In the present study, the success rate for the placebo group with occasional constipation was 24.5%. Based on the differences observed between the two study groups, an additional 40 subjects per group would have been required to observe a statistically significant difference over placebo for the primary endpoint at P < 0.05. This underestimation of the sample size may have led to the introduction of a type II (false negative) error, which in turn might have led to the non-significance between the groups for the primary endpoint.

The self-limiting nature of occasional constipation may sometimes result in spontaneous improvement, which could be perceived by the subjects as a drug-related effect, especially over the short one-week treatment duration. This could also have had an effect on the global assessment of the impact of constipation on the subjects’ daily lives and their laxative preferences, which were based on the subjects’ perceptions of symptom alleviation.

Subjects receiving placebo had to take 17 g maltodextrin in 4-8 ounces of water. This could have led to a lack of standardization of the liquid medium as the volume for placebo was not constant, which in turn could have affected the final osmolality. Also, the patients could have mixed the placebo in hyperosmolar liquids such as fruit juices, which could have led to further variance in the molality of the liquid medium.

The above-mentioned limitations of the current study could be taken into consideration when designing future trials evaluating the effectiveness of PEG 3350 in subjects with occasional constipation.

PEG 3350 at a dose of 17 g, administered once daily for a week, is safe, effective, well tolerated, and may be preferred by subjects over other laxatives in the treatment of occasional constipation.

The author wishes to express his appreciation to all the trial investigators (Table 5). Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was provided by Elphine Telles, PhD, of Cactus Communications. This assistance was funded by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, United States.

| Site | Primary investigator |

| Product Investigations, Inc., Conshohocken, PA | Morris Shelanski, MD |

| Site 2, Turnpike Levittown, NY | Maurice Gunsberger, MD |

| Site 3, South Windsor, CT | Raymond Kurker, MD |

| International Research Services, Inc., Port Chester, NY | Roger A. Villi, MD |

| Hartford Research Center | Anthony Roselli, MD |

| Product Investigations, Inc., Modesto, CA | Clinton E. Prescott, MD |

| International Research Services, Inc, Rockland, ME | Robert Jorden, MD |

| Avon Family Medical Group, Avon, CT | Anthony Roselli, MD |

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 has been shown to be effective in the treatment of chronic constipation in large-scale randomized trials. PEG 3350 (MiraLAX®), an oral over-the-counter (OTC) laxative, administered once-daily over a week, has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to relieve occasional constipation.

Very few data are available regarding the effectiveness of PEG 3350 for the treatment of occasional constipation.

This is the first placebo-controlled study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of PEG 3350 in subjects with occasional constipation after a week’s treatment. PEG 3350, at a dose of 17 g, administered once daily for a week, was safe, effective, and well tolerated, and may be preferred by patients over other laxatives.

The findings and limitations of the current study could be taken into consideration while designing future trials evaluating the effectiveness of PEG 3350 in subjects with occasional constipation.

Occasional constipation is a self-diagnosed condition that is often relieved by lifestyle changes or OTC laxatives. Occasional constipation was defined here as constipation (straining with lumpy or hard stools, or the inability to produce a bowel movement in the last 48 h) that does not resolve on its own with time.

The present study addresses a scarcely investigated topic, occasional constipation. In addition, it reflects a common use of PEG 3350 in clinical practice and therefore it is of considerable interest to determine whether this common off-label use of PEG 3350 is justified.

P- Reviewer: Bassotti G, Soares RLS, Tandon RK S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 692] [Cited by in RCA: 675] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:525-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3130-3137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Belsey J, Greenfield S, Candy D, Geraint M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:938-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wald A, Scarpignato C, Kamm MA, Mueller-Lissner S, Helfrich I, Schuijt C, Bubeck J, Limoni C, Petrini O. The burden of constipation on quality of life: results of a multinational survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Connell AM, Hilton C, Irvine G, Lennard-Jones JE, Misiewicz JJ. Variation of bowel habit in two population samples. Br Med J. 1965;2:1095-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, Kamm MA, Hinkel U, Helfrich I, Schuijt C, Mandel KG. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:917-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sandler RS, Drossman DA. Bowel habits in young adults not seeking health care. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:841-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Sandler RS, Woods MS, Stemhagen A, Chee E, Lipton RB, Farup CE. Epidemiology of constipation (EPOC) study in the United States: relation of clinical subtypes to sociodemographic features. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3530-3540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Walter S, Hallböök O, Gotthard R, Bergmark M, Sjödahl R. A population-based study on bowel habits in a Swedish community: prevalence of faecal incontinence and constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:911-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3379] [Article Influence: 177.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Cottone C, Tosetti C, Disclafani G, Ubaldi E, Cogliandro R, Stanghellini V. Clinical features of constipation in general practice in Italy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Digesu GA, Panayi D, Kundi N, Tekkis P, Fernando R, Khullar V. Validity of the Rome III Criteria in assessing constipation in women. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:1185-1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Available from: http://www.gastro.org/patient-center/digestive-conditions/constipation. Accessed December 15, 2014. |

| 15. | Dupont C, Leluyer B, Maamri N, Morali A, Joye JP, Fiorini JM, Abdelatif A, Baranes C, Benoît S, Benssoussan A. Double-blind randomized evaluation of clinical and biological tolerance of polyethylene glycol 4000 versus lactulose in constipated children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:625-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care. 2001;10:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Petticrew M, Watt I, Sheldon T. Systematic review of the effectiveness of laxatives in the elderly. Health Technol Assess. 1997;1:i-iv, 1-52. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Corazziari E, Badiali D, Bazzocchi G, Bassotti G, Roselli P, Mastropaolo G, Lucà MG, Galeazzi R, Peruzzi E. Long term efficacy, safety, and tolerabilitity of low daily doses of isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in the treatment of functional chronic constipation. Gut. 2000;46:522-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | DiPalma JA, DeRidder PH, Orlando RC, Kolts BE, Cleveland MB. A randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of the safety and efficacy of a new polyethylene glycol laxative. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:446-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bouhnik Y, Neut C, Raskine L, Michel C, Riottot M, Andrieux C, Guillemot F, Dyard F, Flourié B. Prospective, randomized, parallel-group trial to evaluate the effects of lactulose and polyethylene glycol-4000 on colonic flora in chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:889-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schiller LR, Emmett M, Santa Ana CA, Fordtran JS. Osmotic effects of polyethylene glycol. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:933-941. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Di Palma JA, Cleveland MV, McGowan J, Herrera JL. A randomized, multicenter comparison of polyethylene glycol laxative and tegaserod in treatment of patients with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1964-1971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Di Palma JA, Cleveland MV, McGowan J, Herrera JL. An open-label study of chronic polyethylene glycol laxative use in chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:703-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | DiPalma JA, Cleveland MB, McGowan J, Herrera JL. A comparison of polyethylene glycol laxative and placebo for relief of constipation from constipating medications. South Med J. 2007;100:1085-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dipalma JA, Cleveland MV, McGowan J, Herrera JL. A randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol laxative for chronic treatment of chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1436-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cleveland MV, Flavin DP, Ruben RA, Epstein RM, Clark GE. New polyethylene glycol laxative for treatment of constipation in adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. South Med J. 2001;94:478-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sanders JF. Lactulose syrup assessed in a double-blind study of elderly constipated patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1978;26:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wesselius-De Casparis A, Braadbaart S, Bergh-Bohlken GE, Mimica M. Treatment of chronic constipation with lactulose syrup: results of a double-blind study. Gut. 1968;9:84-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Quigley EM, Wald A, Fidelholtz J, Boivin M, Pecher E, Earnest D. Safety and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with chronic constipation: pooled data from two phase III studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:605-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ford AC, Suares NC. Effect of laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2011;60:209-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |