Published online May 6, 2014. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v5.i2.97

Revised: January 22, 2014

Accepted: March 13, 2014

Published online: May 6, 2014

Processing time: 189 Days and 16.2 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the clinical effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) vs endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy (EVS) in the management of gastric variceal (GV) bleeding in terms of variceal rebleeding, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and survival by meta-analysis.

METHODS: Medline, Embase, and CNKI were searched. Studies compared TIPS with EVS in treating GV bleeding were identified and included according to our predefined inclusion criteria. Data were extracted independently by two of our authors. Studies with prospective randomized design were considered to be of high quality. Hazard ratios (HRs) or odd ratios (ORs) were calculated using a fixed-effects model when there was no inter-trial heterogeneity. Oppositely, a random-effects model was employed.

RESULTS: Three studies with 220 patients who had at least one episode of GV bleeding were included in the present meta-analysis. The proportions of patients with viral cirrhosis and alcoholic cirrhosis were 39% (range 0%-78%) and 36% (range 12% to 41%), respectively. The pooled incidence of variceal rebleeding in the TIPS group was significantly lower than that in the EVS group (HR = 0.3, 0.35, 95%CI: 0.17-0.71, P = 0.004). However, the risk of the development of any degree of HE was significantly increased in the TIPS group (OR = 15.97, 95%CI: 3.61-70.68). The pooled HR of survival was 1.26 (95%CI: 0.76-2.09, P = 0.36). No inter-trial heterogeneity was observed among these analyses.

CONCLUSION: The improved effect of TIPS in the prevention of GV rebleeding is associated with an increased risk of HE. There is no survival difference between the TIPS and EVS groups. Further studies are needed to evaluate the survival benefit of TIPS in cirrhotic patients with GV bleeding.

Core tip: This meta-analysis provides evidence-based guidance regarding the effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy on rebleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and survival. The results suggest that transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is more effective than endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding, but is associated with an increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy.

-

Citation: Bai M, Qi XS, Yang ZP, Wu KC, Fan DM, Han GH. EVS

vs TIPS shunt for gastric variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2014; 5(2): 97-104 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v5/i2/97.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v5.i2.97

Variceal hemorrhage occurs in 25%-35% of patients with cirrhosis. Gastric varices (GV) are the origin in about 27% of variceal bleeders[1,2]. In comparison with esophageal varices (EV), the bleeding from GV is more severe. Furthermore, patients with GV bleeding are usually associated with higher mortality than those with EV bleeding[2,3].

Endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy (EVS) has been proved to be effective in the treatment of EV bleeding[4-6]. But, EVS is less successful in the treatment of GV bleeding, probably because of its size, location, and high-volume blood flow[3,7]. Compared to patients with EV, GV patients who accepted EVS treatment were associated with a higher rebleeding rate (23%-90%) and more side effects such as fever and retrosternal and abdominal pain[8,9]. Additionally, Lo et al[10] accomplished a randomized trial and proved that EVS was more effective than endoscopic band ligation in the management of GV bleeding. Recently, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) became more and more popular in the management of complications related to portal hypertension. TIPS was recommended as the second-line therapy for the treatment of acute variceal bleeding and variceal rebleeding in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guideline and British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients[6,11,12].

Currently, both EVS and TIPS were employed for the treatment of GV bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Several studies have evaluated the effect of these two therapies in the management of GV bleeding. Results of these studies were controversial. For example, Mahadeva et al[13] demonstrated a significantly lower rebleeding rate in patients who underwent the TIPS procedure, but Procaccini et al[7] reported similar rebleeding rates between the EVS and TIPS groups[7,13]. Hence, a meta-analysis of the data derived from the published literature would be necessary. The purpose of this study is to provide an evidence-based guidance regarding the effect of EVS and TIPS on variceal rebleeding, HE, and survival by meta-analysis.

We searched Medline (1950 to October 2012, limited in English), Embase (1974 to October 2012), and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, http://www.edu.cnki.net, 1979 to October 2012) using “transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt”, “gastric varices”, and “endoscopic sclerotherapy” as the key words. We also reviewed the citations of the identified articles and manually searched the abstracts from the meetings of the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease, the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, and the World Congress of Gastroenterology.

Studies included in our meta-analysis met the following criteria: (1) participants were adult patients (> 18 years) with at least one episode of GV bleeding; (2) interventions were TIPS vs EVS; and (3) studies reported at least one of the following outcomes: variceal rebleeding, HE, and survival. Study searches and screenings were conducted independently by two of our authors (Bai M, Qi XS). Discrepancies were solved by consensus.

Data were extracted independently by two of our authors (Bai M, Qi XS) using a predefined form. Disagreements were resolved by discussions.

The methodological qualities of the included trials were assessed independently by two investigators (Bai M and Han GH). Studies with prospective randomized design were considered to be of high quality.

GV included GV1 (varices continuous with EV and extending along the lesser curve for about 2-5 cm below the gastroesophageal junction), GV2 (varices, often long and tortuous, extending from the esophagus below the gastroesophageal junction toward the fundus), type 1 isolated GV (IGV1, varices located in the fundus that often are tortuous and complex in shape), and type 2 isolated GV (IGV2, ectopic varices in the antrum, corpus, and around the pylorus)[3].

Variceal rebleeding included rebleeding from all kinds of varices caused by portal hypertension, most commonly EV and GV. GV rebleeding was distinguished from EV rebleeding on the basis of whether active GV bleeding or erosive spots on the GV were observed during endoscopic examination. HE was defined as any episode of clinically overt encephalopathy and was graded according to the West Haven criteria[14].

The statistical package RevMan version 5.0 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) provided by the Cochrane Collaboration was used for all analyses. According to the PRISMA statement, the hazard ratios (HRs) are used for time-to-event outcomes[15]. At first, the observed minus expected difference (O-E) and variance (V) were tried to be calculated directly from the detailed data (observed events and expected events or hazard rates on research and control arm, O-E on research arm and log-rank V) or indirectly from the estimated data (HR and confidence intervals, HR and events in each arm, HR and total events, log-rank test result and the number of events in the two groups)[16,17]. A negative O-E implied that the outcome favoured TIPS. And then, the pooled HR was estimated according to the O-E and V. For dichotomous endpoints which were not reported as time-to-event outcomes, such as HE in the present study, pooled odds ratios (ORs) were calculated by the Mantal-Haenszel model. Significance and 95%CI were provided for the combined HRs and ORs.

According to Higgins et al[18], the χ2Q-test (P < 0.10 was considered to represent significant statistical heterogeneity) and the I2 statistic were applied to investigate inter-trial heterogeneity. A fixed-effect model was employed for the analyses with no significant inter-trial heterogeneity and a random-effect model was employed for those with significant inter-trial heterogeneity. Both the test for publication bias and meta-regression were not performed because less than ten studies were included in the present meta-analysis.

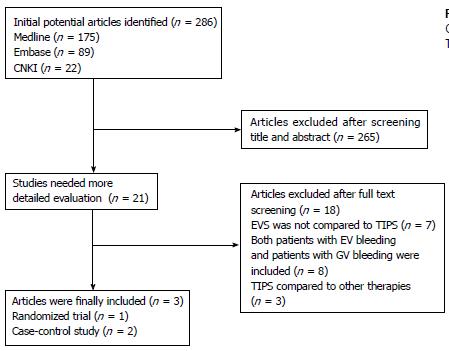

According to our search strategy, 286 articles were identified. Most (n = 265) of these articles were excluded after abstract reading (Figure 1). Of the remaining 17 articles, 14 were excluded after full-text reading for the following reasons: EVS was not compared with TIPS (n = 7); both patients with EV and GV bleeding were included (n = 8); TIPS was compared with therapies other than EVS (n = 3).

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the three included studies[7,13,19]. All of the three studies were published in full-text. TIPS procedures were performed with bare stents in two studies[13,19], and partially with covered stents in the remaining one (Table 1)[7,13,19].

| Ref. | Type of stent | Type of EVS | Randomized | Prospective study | Consecutive patients | Comparable base-line data | Definition of variceal rebleeding | Definition of post-TIPS HE | Lost (TIPS/EVS) |

| Mahadeva et al[13] | Bare | Cyanoacrylate | No | No | No | Yes | NR | NR | 0/0 |

| Lo et al[19] | Bare | Cyanoacrylate | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Rebleeding from GV or EV was defined as the presence of hematemesis or melena with the bleeding source being endoscopically proven to originate from GV or EV, respectively | Patients with altered consciousness levels and elevated arterial ammonia levels requiring hospitalization were recorded as having the complication of hepatic encephalopathy | 1/6 |

| Procaccini et al[7] | 29 with covered stent, 15 with bare stent | Cyanoacrylate | No | No | NR | Yes | Rebleeding was defined by a significant decrease in hemoglobin or hematocrit requiring packed red cell transfusion or evidence of hematemesis or melena with hemodynamic insufficiency | NR | NR/NR |

Only the study by Lo et al[19] was a prospective randomized trial, and was considered to be of high quality. However, the two groups in their study were not comparable in the number of previous variceal bleeding episodes. The rest two trials were retrospective studies and were considered as low-quality studies according to our quality assessment criteria. However, these two studies have study groups which were comparable in base-line data.

The three studies included 220 patients altogether. Almost 35% and 82% of the patients in the study by Mahadeva et al[13] and Lo et al[19] had GV1, respectively[13,19]. Three patients in the study by Lo et al[19] had IGV. The study by Procaccini et al[7] did not classify GV according to its location. The pooled proportions of patients with viral cirrhosis and alcoholic cirrhosis were 39% (range 0%-78%) and 36% (range 12%-41%), respectively. Most of the patients in the study by Mahadeva et al[13] were Child-Pugh C (44%) and more than half of the patients in the study by Lo et al[19] were Child-Pugh B (54%, Table 2).

| Ref. | Patients screened | Patients included Total/TIPS/EVS | Age TIPS/EVS | Gender TIPS/EVS male (female) | Child-Pugh classes TIPS/EVS | Etiology | GV anatomy TIPS/EVS | ||||||

| A | B | C | Viral TIPS/EVS | Alcohol TIPS/EVS | Others TIPS/EVS | GOV1 | GOV2 | IGV | |||||

| Mahadeva et al[13] | NR | 43/20/23 | 52/55 | 13 (7)/15 (8) | 4/4 | 6/8 | 10/9 | 0/0 | 12/14 | 8/9 | 13/15 | 7/8 | 0/0 |

| Lo et al[19] | 460 | 72/35/37 | 55/52 | 25 (10)/28 (9) | 9/12 | 20/19 | 6/6 | 30/26 | 4/8 | 1/3 | 19/17 | 14/19 | 2/1 |

| Procaccini et al[7] | NR | 105/44/61 | 52/54.5 | 26 (18)/43 (18) | NR | NR | NR | 14/16 | 17/24 | 13/21 | NR | NR | NR |

TIPS shunt stenosis, final patency rate of TIPS shunt, number of endoscopic therapy per patient, patient crossover to TIPS, incidences of variceal rebleeding and HE, and survival were assessed in all of the three studies. The incidences of TIPS shunt stenosis were lower than 25% during the follow-up in the TIPS group in all of the included studies. On average, at least 2-3 EVSs were needed to achieve variceal obliteration for the patients in the EVS group.

Both the study by Mahadeva et al[13] and the study by Lo et al[19] demonstrated lower incidences of clinical failure in the TIPS group than in the EVS group. However, the difference between groups was not statistically significant[13,19]. Additionally, 2, 1, and 7 patients in the ET group crossed over to the TIPS group in the study by Mahadeva et al[13], the study by Lo et al[19] and the study by Procaccini et al[7], respectively (Table 3).

| Ref. | Successful stent placement | Shunt stenosis | Finalpatency | EVS per patient mean ± SD | Patients crossing over to TIPS | Clinical failure TIPS/EVS | Variceal rebleeding TIPS/EVS | HE TIPS/EVS | Refractory HE TIPS/EVS | Death TIPS (%)/EVS (%) |

| Mahadeva et al[13] | 18/20 (90) | 2/20 (10) | 16/20 (80) | 3 ± 1.5 | 2 (9) | 2 (10)/4 (17) | 4 (20)/8 (35) | 21 (10)/0 (0) | NR | 1 (5)/2 (9) |

| Lo et al[19] | 35/35 (100) | 8/35 (23) | 27/35 (77) | 3.3 ± 1.4 | 1 (3) | 1 (3)/3 (8) | 7 (20)/19 (51) | 9 (26)/1 (3) | NR | 16 (46)/12 (32) |

| Procaccini et al[7] | NR | 6/42 (14) | 36/42 (86) | 2 ± median | 7 (11) | NR | UA | 11 (25)/1 (2) | NR | 14 (32)/17 (28) |

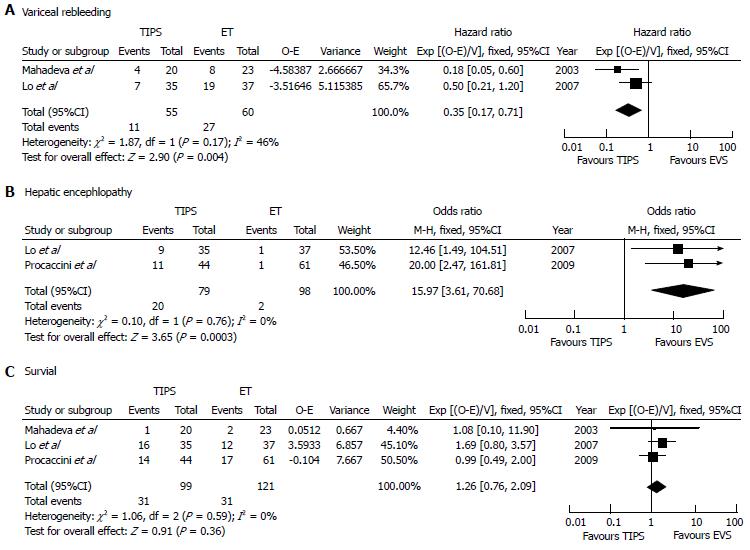

The risk of variceal rebleeding was significantly lower in the TIPS group in two of the included studies[13,19]. The pooled risk of variceal rebleeding in the TIPS group was significantly lower (Figure 2A, HR = 0.35, 95%CI: 0.17-0.71, P = 0.004) than that in the EVS group. Inter-trial heterogeneity of this analysis was not significant (P = 0.17, I2 = 46%). The study by Parocaccini et al[7] was not included in this analysis, because it had insufficient information for the calculation of O-E and V.

Two of the three studies reported the probabilities of patients with GV rebleeding[13,19]. In the study by Lo et al[19], more patients with GV rebleeding were observed in the EVS group (Log-Rank test, P = 0.01)[19]. However, the study by Procaccini et al[7] demonstrated similar incidences of GV rebleeding in the TIPS and EVS groups (Fisher’s exact test, 72 h: P = 0.71, 3 mo: P = 0.25, 1 year: P = 0.16)[7]. For GV rebleeding, the combination of these results could not be performed because of the unfeasibility of the detailed data of this outcome.

A higher risk of HE was reported in the patients who underwent TIPS procedure in all of the included studies[7,13,19]. Only the difference between groups in the study by Mahadeva et al[13] was not significant, probably because only the patients with severe HE were counted. The pooled risk of developing any degree of HE was higher in the TIPS group (Figure 2B, OR = 15.97, 95%CI: 3.61-70.68, P < 0.001). Two studies with 177 patients were involved in the estimation of the pooled OR of HE[7,19]. No significant heterogeneity was observed among the involved studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.76).

In all of the three included studies, patients with TIPS and EVS did not demonstrate a significant difference in survival. The heterogeneity of this analysis was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.59), and the pooled HR of survival was 1.26 (Figure 2C, 95%CI: 0.76-2.09, P = 0.36).

According to this meta-analysis of three controlled trials which compared EVS and TIPS in the treatment of GV bleeding due to portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients, TIPS is more effective in the prevention of GV rebleeding. Two of the three included studies reported a significant reduction of variceal rebleeding rate in the TIPS group, and the rest one demonstrated similar efficacy between the two therapies[7,13,19]. Probably, the cause of the distinct results is that Procaccini et al[7] used a different method to present their results. They removed the deaths from the analysis, which led to a unusually lower rate of GV rebleeding at 1 year than that at 3 mo[7]. Consequently, we could not get the accurate number of patients with GV rebleeding. Therefore, this study was not pooled in the estimation of GV rebleeding risk.

The advantages of TIPS in the prevention of GV rebleeding were implied in previous studies. Two observational studies proved that EVS was more effective in the control of EV rebleeding than GV rebleeding[2,20]. The effect of TIPS in the prevention of GV rebleeding was similar to its effect in the prevention of EV rebleeding[21]. In the patients with previous EV bleeding, several randomized trials have confirmed that TIPS was better than EVS in the reduction of variceal rebleeding[22-24]. Accordingly, TIPS may perform better in the management of GV rebleeding than EVS.

All of the three studies demonstrated higher incidences of HE in the patients who received TIPS than the patients treated by EVS. In the study by Mahadeva et al[13], the number of patients with severe HE but not overt HE was demonstrated. Contrarily, the other two studies did not show the number of patients with severe HE[7,19]. Hence, the meta-analysis of HE just included the later two studies. A significantly higher incidence of HE in the patients treated by TIPS is suggested by the pooled OR. The increased portal vein blood bypassing the liver is considered as one of the most reasonable causes of the increased HE risk after TIPS procedure. According to the study by Watanabe et al[25], the patients with GV were more frequently associated with large gastro-renal shunts and chronic HE when compared with the patients with EV. Riggio et al[26] proved that cirrhotic patients with recurrent or persistent HE were more commonly associated with large spontaneous portosystemic shunts. According to the results of these studies and our thirteen years of experience in performing TIPS procedure, the embolization of the large spontaneous shunt during a TIPS procedure could most likely reduce hepatofugal blood flow and then reduce the post-TIPS HE risk.

The improvement of TIPS in the prevention of GV rebleeding did not improve patient survival, which was most likely due to the expense of the increased risk of HE. Garcia-Pagan and his colleagues proved that TIPS could improve the survival of the patients with acute variceal bleeding and high treatment-failure risk[27]. With a little regret, this study did not include patients who had variceal bleeding from GV and did not estimate the effect of TIPS and endoscopic therapy in the subgroup of patients with GV. Thus, further studies are needed to evaluate whether TIPS could improve the survival of high-risk patients with acute GV bleeding.

Because most of the patients accepted bare-stent TIPS procedure in the three included studies, 10%-23% of them had shunt stenosis during the follow-up[7,13,19]. Over the last decade, the use of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents improved the shunt patency rate[28-30]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the use of covered-stents could even reduce the post-TIPS HE risk[31]. With this improvement, the role of TIPS in the treatment of GV probably would be up-graded in the near future.

Several limitations were accompanied with this meta-analysis. First, only one of the included studies was a randomized controlled trial. Even the offered baseline data of the two groups were comparable in the two nonrandomized studies, the use of randomization could balance the known and unknown confounding factors[32]. Second, different endpoints were used for the estimation of one outcome, which suggested that it was inappropriate to pooled them together. For example, the study by Mahadeva et al[13] used the number of patients with severe HE but the remaining two studies used the number of patients with overt HE to demonstrate the risk of post-intervention HE. The third limitation was that only one study provided raw data by the type of GV and none of the three studies provided raw data by Child-Pugh class[19]. Therefore, subgroup analyses according to the type of GV and degree of liver function were precluded.

In conclusion, the improvement of TIPS in the prevention of GV rebleeding is associated with an increased HE risk. TIPS procedure did not improve survival of patients with GV bleeding. The role of covered-stent TIPS in the management of patients with GV bleeding should be evaluated in the near future.

Gastric varices (GV) are the origin in about 27% variceal bleeders with hepatic cirrhosis. Patients with GV bleeding are usually associated with higher mortality than those with esophageal variceal bleeding. Both endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy (EVS) and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) were employed for the treatment of GV bleeding. Several studies have evaluated the effect of EVS vs TIPS on GV bleeding, and the results of these studies were controversial.

In the area of GV bleeding treatment, the research hotspot is how to reduce GV rebleeding rate and improve patient survival and life quality.

The present meta-analysis found out that patients with GV bleeding who underwent TIPS procedure had lower incidence of variceal rebleeding than those who underwent EVS treatment. However, TIPS procedure increased the HE risk and did not improve the patient survival.

The results of the present meta-analysis suggest that the use of TIPS procedure for the treatment of GV bleeding could reduce the risk of rebleeding. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effect of TIPS procedure on survival in patients with cirrhosis and GV bleeding.

GV included GV1 (varices continuous with EV and extending along the lesser curve for about 2–5 cm below the gastroesophageal junction), GV2 (varices, often long and tortuous, extending from the esophagus below the gastroesophageal junction toward the fundus), type 1 isolated GV (IGV1, varices located in the fundus that often are tortuous and complex in shape), and type 2 isolated GV (IGV2, ectopic varices in the antrum, corpus, and around the pylorus).

It is important to evaluate the effect of TIPS vs EVS in the treatment of patients with GV bleeding. A few studies on this topic showed controversial results. This meta-analysis demonstrates interesting results which are helpful for clinical practice and further clinical research. This paper was well written and is very suitable for publication.

P- Reviewers: De Silva AP, Ferreira CN, Hori T, Li ZF, Trapero-Marugan M S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Sharara AI, Rockey DC. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:669-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (42)] |

| 3. | Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. A pathophysiologic, gastroenterologic, and radiologic approach to the management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1175-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, Korula J, Lieberman D, Saeed ZA, Reveille RM, Sun JH, Lowenstein SR. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1527-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Paquet KJ, Feussner H. Endoscopic sclerosis and esophageal balloon tamponade in acute hemorrhage from esophagogastric varices: a prospective controlled randomized trial. Hepatology. 1985;5:580-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jalan R, Hayes PC. UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2000;46 Suppl 3-4:III1-III15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Procaccini NJ, Al-Osaimi AM, Northup P, Argo C, Caldwell SH. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate versus transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for gastric variceal bleeding: a single-center U.S. analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Trudeau W, Prindiville T. Endoscopic injection sclerosis in bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:264-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarin SK. Long-term follow-up of gastric variceal sclerotherapy: an eleven-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001;33:1060-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2005;41:386-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The Role of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) in the Management of Portal Hypertension: update 2009. Hepatology. 2010;51:306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Mahadeva S, Bellamy MC, Kessel D, Davies MH, Millson CE. Cost-effectiveness of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl) glue injections versus transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of acute gastric variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2688-2693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in RCA: 1410] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65-W94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21613] [Cited by in RCA: 18165] [Article Influence: 1135.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4738] [Cited by in RCA: 4953] [Article Influence: 275.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815-2834. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46505] [Article Influence: 2113.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Lo GH, Liang HL, Chen WC, Chen MH, Lai KH, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Chan HH, Pan HB. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy. 2007;39:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Korula J, Chin K, Ko Y, Yamada S. Demonstration of two distinct subsets of gastric varices. Observations during a seven-year study of endoscopic sclerotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stanley AJ, Jalan R, Ireland HM, Redhead DN, Bouchier IA, Hayes PC. A comparison between gastric and oesophageal variceal haemorrhage treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cabrera J, Maynar M, Granados R, Gorriz E, Reyes R, Pulido-Duque JM, Rodriguez SanRoman JL, Guerra C, Kravetz D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus sclerotherapy in the elective treatment of variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:832-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cello JP, Ring EJ, Olcott EW, Koch J, Gordon R, Sandhu J, Morgan DR, Ostroff JW, Rockey DC, Bacchetti P. Endoscopic sclerotherapy compared with percutaneous transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt after initial sclerotherapy in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:858-865. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Rössle M, Deibert P, Haag K, Ochs A, Olschewski M, Siegerstetter V, Hauenstein KH, Geiger R, Stiepak C, Keller W. Randomised trial of transjugular-intrahepatic-portosystemic shunt versus endoscopy plus propranolol for prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet. 1997;349:1043-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Watanabe K, Kimura K, Matsutani S, Ohto M, Okuda K. Portal hemodynamics in patients with gastric varices. A study in 230 patients with esophageal and/or gastric varices using portal vein catheterization. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:434-440. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Riggio O, Efrati C, Catalano C, Pediconi F, Mecarelli O, Accornero N, Nicolao F, Angeloni S, Masini A, Ridola L. High prevalence of spontaneous portal-systemic shunts in persistent hepatic encephalopathy: a case-control study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1158-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, Laleman W, Appenrodt B, Luca A, Abraldes JG, Nevens F, Vinel JP, Mössner J, Bosch J. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L, Bilbao JI, Bosch J, Rousseau H, Vinel JP. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Charon JP, Alaeddin FH, Pimpalwar SA, Fay DM, Olliff SP, Jackson RW, Edwards RD, Robertson IR, Rose JD, Moss JG. Results of a retrospective multicenter trial of the Viatorr expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1219-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bureau C, Pagan JC, Layrargues GP, Metivier S, Bellot P, Perreault P, Otal P, Abraldes JG, Peron JM, Rousseau H, Bosch J, Vinel JP. Patency of stents covered with polytetrafluoroethylene in patients treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: long-term results of a randomized multicentre study. Liver Int. 2007;27:742-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yang Z, Han G, Wu Q, Ye X, Jin Z, Yin Z, Qi X, Bai M, Wu K, Fan D. Patency and clinical outcomes of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents versus bare stents: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1718-1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2379] [Cited by in RCA: 2160] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |