Published online May 6, 2013. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v4.i2.23

Revised: January 13, 2013

Accepted: January 23, 2013

Published online: May 6, 2013

Processing time: 149 Days and 8.3 Hours

AIM: To compare the eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and ulcer recurrence of standard triple therapy (STT) and levofloxacin based therapy (LBT).

METHODS: Seventy-four patients with perforated duodenal ulcer treated with simple closure and found to be H. pylori infected on 3 mo follow up were randomized to receive either the STT group comprising of amoxicillin 1 g bid, clarithromycin 500 mg bid and omeprazole 20 mg bid or the LBT group comprising of amoxicillin 1 g bid, levofloxacin 500 mg bid and omeprazole 20 mg bid for 10 d each. The H. pylori eradication rates, side effects, compliance and the recurrence of ulcer were assessed in the two groups at 3 mo follow up.

RESULTS: Thirty-four patients in the STT group and 32 patients in the levofloxacin group presented at 3 mo follow up. H. pylori eradication rates were similar with STT and the LBT groups on intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (69% vs 80%, P = 0.425) and (79% vs 87%, P = 0.513) by per-protocol (PP) analysis respectively. Ulcer recurrence in the STT and LBT groups on ITT analysis was (20% vs 14%, P = 0.551) and (9% vs 6%, P = 1.00) by PP analysis. Compliance and side effects were also comparable between the groups. A complete course of STT costs Indian Rupees (INR) 1060.00, while LBT costs only INR 360.00.

CONCLUSION: H. pylori eradication rates and the rate of ulcer recurrence were similar between the STT and LBT. The LBT is a more economical option compared to STT.

-

Citation: Gopal R, Elamurugan TP, Kate V, Jagdish S, Basu D. Standard triple versus levofloxacin based regimen for eradication of

Helicobacter pylori . World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2013; 4(2): 23-27 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v4/i2/23.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v4.i2.23

Several studies have proved that the eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) decreased the recurrence of ulcer in patients who had undergone simple closure for perforation[1,2]. A proton pump inhibitor with two antibiotics, amoxicillin and clarithromycin, is the commonly used regimen for H. pylori eradication[3]. Although it has been the recommended first line therapy for a long period of time[4-6], recent studies report unacceptably low eradication rates[7-9]. This is attributed to the development of resistance to clarithromycin. Levofloxacin based therapy (LBT) has been recently reported to have higher and consistent eradication rates as a first line therapy in H. pylori eradication[10-12]. LBT represents a better alternative to clarithromycin therapy as it meets the criteria set for H. pylori treatment: effectiveness, simplicity and safety.

Limited studies have been reported comparing the eradication rates for H. pylori between standard triple therapy (STT) and LBT[10]. Hence, this study was done to compare the efficacy of STT to LBT as a first line therapy for the eradication of H. pylori and the prevention of ulcer recurrence in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer following simple closure.

The study was conducted in the Department of Surgery, JIPMER, Puducherry, a tertiary care hospital in south India between September 2009 and August 2011, over a period of 23 mo. The study was conducted as an open-label prospective randomized trial. The study was cleared by the Institute Research Council and the Ethics Committee.

All consecutive patients who presented to the hospital with perforated duodenal ulcer were considered eligible for the study. Those patients who were found to have gastric ulcer perforation, upper gastro intestinal disorders, re-perforations or who had undergone any definitive surgery for perforated peptic ulcer were excluded from the study. At 3 mo follow up, following simple closure of the perforated duodenal ulcer, the patients found to be positive for H. pylori infection were included in the study.

All recruited patients were subjected to upper gastro intestinal endoscopy using a video endoscope (EG 3400; Pentax, Montvale, NJ, United States) under topical anesthesia using 2% lignocaine viscous. Four gastric mucosal biopsies (two each from the gastric corpus and the antrum) were taken using standard endoscopic biopsy forceps. Two of these were used for urease test and the other two for histology after Giemsa staining. All endoscopies were done by an experienced endoscopist.

Diagnosis of H. pylori was made by urease test and histology by Giemsa stain. Urease test was done using a urea solution prepared and standardized in our institute[13]. The solution was observed at room temperature until 24 h of inoculation with two gastric mucosal biopsies. The change of color of the solution from yellow to pink was considered as a positive test for H. pylori infection. Histology was done by Giemsa stain of the biopsies for identification of H. pylori. If either or both the tests were positive, the patient was considered to have a positive H. pylori status. If both the tests were negative, the patient was considered to be negative for H. pylori infection.

Patients positive for H. pylori were randomized into two groups using the sealed envelope technique and computer generated random numbers. One group received the STT regimen while the other received LBT. The STT comprised of amoxicillin 1 g bid, clarithromycin 500 mg bid and omeprazole 20 mg bid and the LBT comprised of amoxicillin 1 g bid, levofloxacin 500 mg bid and omeprazole 20 mg bid for 10 d each.

Follow up of these patients was done at 3 mo following therapy. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was done at the follow up visit to assess the eradication rates of H. pylori for both the groups. Urease test and histology were done on the gastric mucosal biopsies to diagnose H. pylori status. The presence or absence of ulcer in these patients was also noted in the follow up endoscopy. Patients who were found to have a positive H. pylori status, as evidenced by either a positive urease test or a positive histology, were considered as a treatment failure. The compliance to the regimens and the side effect profile were studied through a questionnaire in the patients’ own language, handed over at the time of follow up.

The primary outcome of the study was eradication of H. pylori infection. The secondary outcomes were ulcer recurrence, side effects, compliance and the cost of the regimen.

Study design is an open-label prospective randomized superiority trial. The sample size calculations were done based on our study with the eradication rates for STT[14]. A sample size of 35 in each group was determined for the power of the study to be 0.80. Statistical analysis for the observations were done using Graphpad Instat Software version 3 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA, United States). Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the statistical significance of the H. pylori eradication rates, ulcer recurrence rates, side effects of, and compliance to either regimen.

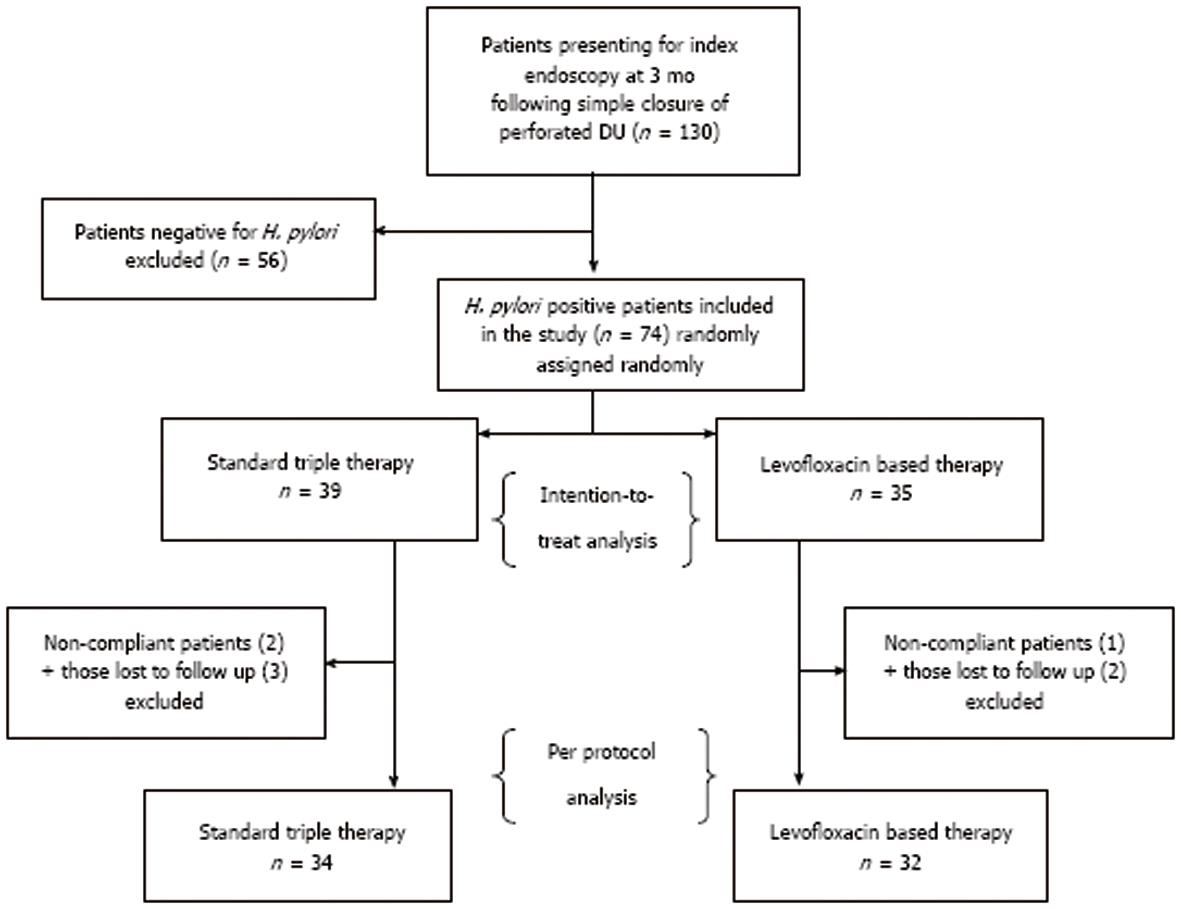

At 3 mo follow up, 130 patients presented for index endoscopy. Seventy four of these 130 patients were diagnosed to have H. pylori infection by urease test and/or histology. These 74 patients were randomized into two groups to receive either the STT (n = 39) or the LBT (n = 35).

In the STT group, 2 patients were non-compliant and 3 were lost to follow up. In the LBT group, 1 patient was non-compliant and 2 patients were lost to follow up. Sixty-six patients presented for the 3 mo follow up, which included 34 patients in the STT group and 32 patients in the levofloxacin group. These 66 patients were included in the per-protocol analysis, as shown in Figure 1. The eradication rates for H. pylori, ulcer recurrence rates, side effects and compliance to the two treatment regimes were analyzed in these patients. The patients in the STT group were in the age group of 19-65 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 38 ± 11.99 years, and the LBT group had patients between 20 and 75 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 43.00 ± 12.25 years. The mean of the ages of the patients in both the groups were statistically comparable (P = 0.0822). The gender distribution in the groups also did not show any significant difference with 37/39 (95%) in the STT and 34/35 (97%) in the LBT being male (P = 1.00). The eradication rates for H. pylori infection by intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis for STT group was 27/34 (79%) and for the LBT group it was 28/32 (87%). The difference was not significant (69% vs 80%, P = 0.425). There was no difference in the eradication rates by per protocol (PP) analysis either (79% vs 87%, P = 0.513). The rate of ulcer recurrence between the groups was also analyzed at the follow up endoscopy. There were only 3 cases with recurrent ulcer in the standard therapy arm and only 2 in the LBT arm. The rate of ulcer recurrence between the groups were not significant by ITT or PP analysis (20% vs 14%, P = 0.551; 9% vs 6%, P = 1.00, respectively). Both the groups showed good compliance to therapy (94% in the STT group and 97% in the LBT). There was no significant difference between the groups in both ITT and PP analysis (P = 0.713, respectively). Side effects of both the treatment regimens were analyzed (Table 1).

| Side effect | Standard triple therapy | Levofloxacin based therapy | P value1 |

| Diarrhea | 26% | 19% | 0.3096 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 12% | 22% | 0.0892 |

| Bloating | 18% | 19% | 1.0000 |

| Epigastric pain | 21% | 12% | 0.1871 |

| Rashes | 6% | 3% | 0.4977 |

In the STT arm, diarrhea was the most common side effect, with a prevalence of 26%. Other side effects reported were epigastric pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting and rashes, in the decreasing order of frequency. In the LBT arm, the most common side effect complained of was nausea and vomiting (22%), followed by diarrhea, bloating, epigastric pain and rashes. There was no significant difference between the side effect profiles of the two groups. The cost of the complete course of STT was 1060.00 Indian Rupees (INR) and 360.00 INR for the LBT.

H. pylori has been identified as the most important risk factor for peptic ulcer disease[15,16]. Significant decrease in the rate of ulcer recurrence was reported in patients with perforated peptic ulcer following simple closure and eradication of H. pylori[2,15]. However, the choice of the optimal regimen for H. pylori eradication is debated[17]. The STT, using amoxicillin, clarithromycin and omeprazole, is one of the widely used regimens for H. pylori eradication[17]. Different studies have shown different rates of eradication with this regimen, ranging between 76% and 90%[18]. The emergence of resistance of the organism to clarithromycin has urged researchers to look for alternatives to the STT. The sequential therapy and levofloxacin based regimens are two of the newly recommended combinations[18-22]. Levofloxacin based regimens were used as rescue regimens in case of failure with standard regimen[23]. The efficacy of this combination as a first line regimen has not been studied extensively. Data regarding the efficacy of this regimen in the Indian setting is lacking.

The present study showed an eradication rate of 79% and 69% with the STT and 87% and 80% with the LBT in PP and ITT analysis respectively. Gisbert et al[10] studied the efficacy of LBT as the first line treatment of H. pylori and found eradication rates of 88% and 84% under PP and ITT analysis respectively, which are comparable to the results of our study. Schrauwen et al[24] from the Netherlands found that therapy with the levofloxacin regimen was very effective in the eradication of H. pylori. There are no reports to date of STT being superior to the former. The resistance to fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, has been reported to be low in most populations across the globe[25]. This is one reason that encourages the use of this drug in eradication regimens.

Bose et al [2], in a study conducted in our institute, found that eradication of H. pylori infection decreases the rate of ulcer recurrence significantly. At 3 mo follow up, they found that ulcer recurrence in patients in whom H. pylori was eradicated was only 18.6% compared to a 70% in the non-eradicated patients (P = 0.003).

In the present study, ulcer recurrence rates in both groups were comparable under both PP and ITT analyses. The STT group had ulcer recurrence rates of 20% and 9% under ITT and PP analysis respectively, while the levofloxacin group had ulcer recurrence rates of 14% and 6% respectively. The ulcer recurrence rates observed at 3 mo follow up in the STT group were comparable to that seen in the earlier study from the same center[2].

The side effect profile in both groups did not show any significant difference with regard to any of the symptoms. The more common side effects of the individual agents were chosen, assessed using a questionnaire and analyzed. Diarrhea (26%), followed by epigastric pain (21%), was the most reported side effect in the STT group. The levofloxacin group complained mostly of nausea and vomiting (22%), with diarrhea and bloating occurring in 19% of patients. The irritant effect of amoxicillin on the gastrointestinal tract and the alteration of the native gut flora by the high dosage can explain the high incidence of diarrhea in both treatment groups[26]. One of the major side effects of clarithromycin therapy is mild to moderate epigastric pain. This can explain the relatively high incidence of this symptom in the STT group.

Both study groups had comparable compliance to treatment in our study. The STT group had compliance rates of 94% and 87% in the PP and ITT analysis respectively, compared to 97% and 91% in the levofloxacin group by PP and ITT respectively. These compliance rates are comparable to those seen in western studies. Vaira et al[20] reported a compliance rate of 94% in patients receiving STT. Gisbert et al[10] reported similar adherence to treatment in his study among patients receiving both STT and LBT.

Clarithromycin is the costliest component of the STT. Replacing it with less expensive levofloxacin helps to reduce the cost of treatment significantly. The cost analysis done as a part of the present study has shown that a complete course of the STT costs 1060.00 INR compared to 360.00 INR of the LBT, as on August 1, 2011. This economical convenience also favors the use of the latter treatment regimen.

The results of the present study show a higher trend of eradication of H. pylori and prevention of ulcer recurrence in patients who received LBT when compared to those who were administered STT, but statistical analysis failed to show any significance in these differences.

Thus, from the observations of this study, we conclude that LBT is an equally effective alternative to the STT with regard to H. pylori eradication rates, prevention of ulcer recurrence, compliance and side effect profile. The lesser cost of the LBT makes it an economical option for treatment of H. pylori.

Standard triple therapy (STT), with a proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics, amoxicillin and clarithromycin, is the commonly used regimen for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication. Recent studies report low eradication rates due to the development of resistance to clarithromycin.

Levofloxacin based therapy (LBT) has been recently reported to have higher and consistent eradication rates as a first line therapy in H. pylori eradication.

Limited studies have been reported comparing the eradication rates for H. pylori between STT and LBT.

LBT represents a comparable alternative to clarithromycin therapy as it meets the criteria set for H. pylori treatment: effectiveness, simplicity and safety.

This is an interesting study comparing the use of clarithromycin and levofloxacin based eradication therapy for H. pylori infection.

P- Reviewer Yen HH S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yan JL

| 1. | Ng EK, Lam YH, Sung JJ, Yung MY, To KF, Chan AC, Lee DW, Law BK, Lau JY, Ling TK. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents recurrence of ulcer after simple closure of duodenal ulcer perforation: randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2000;231:153-158. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Bose AC, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Parija SC. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents recurrence after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:345-348. [PubMed] |

| 3. | El-Nakeeb A, Fikry A, Abd El-Hamed TM, Fouda el Y, El Awady S, Youssef T, Sherief D, Farid M. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on ulcer recurrence after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. Int J Surg. 2009;7:126-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cutler AF, Vakil N. Evolving therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: efficacy and economic impact in the treatment of patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3:1528-1534. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, O’Morain C, Hungin AP, Jones R, Axon A, Graham DY, Tytgat G. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:167-180. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Dzieniszewski J, Jarosz M. Guidelines in the medical treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57 Suppl 3:143-154. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, Kist M, Lopez-Brea M, Hirschl AM, Andersen LP, Goossens H, Glupczynski Y. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut. 2013;62:34-42. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Saracino IM, Zullo A, Holton J, Castelli V, Fiorini G, Zaccaro C, Ridola L, Ricci C, Gatta L, Vaira D. High prevalence of primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates in Italy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:363-365. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Egan BJ, Katicic M, O’Connor HJ, O’Morain CA. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 1:31-37. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gisbert JP, Fernández-Bermejo M, Molina-Infante J, Pérez-Gallardo B, Prieto-Bermejo AB, Mateos-Rodríguez JM, Robledo-Andrés P, González-García G. First-line triple therapy with levofloxacin for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:495-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qian J, Ye F, Zhang J, Yang YM, Tu HM, Jiang Q, Shang L, Pan XL, Shi RH, Zhang GX. Levofloxacin-containing triple and sequential therapy or standard sequential therapy as the first line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication in China. Helicobacter. 2012;17:478-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Manfredi M, Bizzarri B, de’Angelis GL. Helicobacter pylori infection: sequential therapy followed by levofloxacin-containing triple therapy provides a good cumulative eradication rate. Helicobacter. 2012;17:246-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jones VS, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Badrinath S, Amarnath SK, Ratnakar C. Standardization of urease test for detection of Helicobacter pylori. Indian J Med Microbiol. 1997;15:181-183. |

| 14. | Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Badrinath S. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the ulcer recurrence rate after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer: retrospective and prospective randomized controlled studies. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1054-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, Henderson C, Howden CW, Metz DC. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011;84:102-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sebastian M, Chandran VP, Elashaal YI, Sim AJ. Helicobacter pylori infection in perforated peptic ulcer disease. Br J Surg. 1995;82:360-362. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Wu J, Sung J. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Hong Kong Med J. 1999;5:145-149. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gisbert JP, Calvet X, O’Connor A, Mégraud F, O’Morain CA. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a critical review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:313-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, Gatta L, Ricci C, Perna F, Hassan C, Bernabucci V, Tampieri A, Morini S. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556-563. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Valooran GJ, Kate V, Jagdish S, Basu D. Sequential therapy versus standard triple drug therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer following simple closure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1045-1050. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gisbert JP, Pérez-Aisa A, Bermejo F, Castro-Fernández M, Almela P, Barrio J, Cosme A, Modolell I, Bory F, Fernández-Bermejo M. Second-line therapy with levofloxacin after failure of treatment to eradicate helicobacter pylori infection: time trends in a Spanish Multicenter Study of 1000 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:130-135. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Gisbert JP. Rescue Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection 2012. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:974594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schrauwen RW, Janssen MJ, de Boer WA. Seven-day PPI-triple therapy with levofloxacin is very effective for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Neth J Med. 2009;67:96-101. [PubMed] |

| 25. | De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Ierardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-414. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Tripathi KD. Drugs for peptic ulcer. Essential of Medical Pharmacology. 5thed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers 2003; 587-598. |