Published online Dec 6, 2011. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v2.i6.46

Revised: November 4, 2011

Accepted: November 10, 2011

Published online: December 6, 2011

AIM: To investigate the use of Savary-Gilliard marked dilators in tight esophageal strictures without fluoroscopy.

METHODS: Seventy-two patients with significant dysphagia from benign strictures due to a variety of causes were dilated endoscopically. Patients with achalasia, malignant lesions or external compression were excluded. The procedure consisted of two parts. First, a guide wire was placed through video endoscopy and then dilatation was performed without fluoroscopy. In general, “the rule of three” was followed. Effective treatment was defined as the ability of patients, with or without repeated dilatations, to maintain a solid or semisolid diet for more than 12 mo.

RESULTS: Six hundred and sixty two dilatations in a total of 72 patients were carried out. The success rate for placement of a guide wire was 100% and for dilatation 97%, without use of fluoroscopy, after 6 mo to 4 years of follow-up. The number of sessions per patient was between 1 and 7, with an average of 2 sessions. The ability of patients, after 1 or more sessions of dilatation, to maintain a solid or semisolid diet for more than 12 mo was obtained in 70 patients (95.8%). For very tight esophageal strictures, all patients improved clinically without complications after the endoscopic procedure without fluoroscopy, but we noted 3 failures.

CONCLUSION: Dilatation using Savary-Gilliard dilators without fluoroscopy is safe and effective in the treatment of very tight esophageal strictures if performed with care.

- Citation: Kabbaj N, Salihoun M, Chaoui Z, Acharki M, Amrani N. Safety and outcome using endoscopic dilatation for benign esophageal stricture without fluoroscopy. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2011; 2(6): 46-49

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v2/i6/46.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v2.i6.46

Esophageal strictures are a problem frequently encountered by gastroenterologists and can be subdivided into malignant and benign origin. Malignant esophageal strictures are mainly caused by primary esophageal cancer but can also be caused by extra esophageal malignancies that compress the esophagus[1].

The most common causes of benign esophageal strictures include peptic injury, Schatzki’s ring, esophageal web, radiation injury, caustic injury and anastomotic strictures.

Upper endoscopy is the diagnostic procedure of choice for the detection of an esophageal stricture and its underlying cause. Nevertheless, it is mandatory that biopsy samples are taken to confirm whether the stricture is benign or malignant in nature[1].

Dilatation of esophageal strictures is a commonly performed procedure used to relieve dysphagia due to esophageal strictures. In clinical practice, fluoroscopy is recommended for monitoring the position of a guide wire and dilator[2-5]. Some authors, however, believe that fluoroscopy is not necessary for dilatation. The aim of this study is to describe our experience using a guide wire and marked Savary-Gilliard dilators (Figure 1) without the use of fluoroscopy.

Between January 2005 and January 2011, 72 consecutive patients (45 females, 27 males, aged 18 to 75 years old, mean age 42 years) with benign esophageal strictures were referred to our unit for dilatation because of persistent or recurrent dysphagia. Benign stricture was ascertained using endoscopy and biopsy. There were 72 benign lesions. The diagnoses are summarized in Table 1. Patients with achalasia, malignant lesions and external compression were excluded. All our patients had various degrees of dysphagia. A total of 662 dilations were performed for 72 patients who had various degrees of dysphagia prior to each session. X-ray studies of the geography of the strictures were performed for each case before treatment.

| Benign strictures | n (%) |

| Peptic injury | 30 (41.6) |

| Plummer Vinson web | 20 (27.7) |

| Radic stricture | 9 (12.5) |

| Caustic stricture | 6 (8.3) |

| Anastomotic stricture | 6 (8.3) |

| Post infectious stricture | 1 (1.3) |

Examinations were performed with Olympus GIF-XP or Pentax EPK-700. Dilatation was performed with marked Savary-Gilliard dilators.

If the stricture could be passed with a paediatric endoscope, the guide wire was placed through endoscopic guidance. Thereafter, dilatation was performed without fluoroscopy. For very tight esophageal strictures, we inserted the guide wire through the tight stricture into the esophageal lumen and Savary-Gilliard dilatation was also used without fluoroscopy. In general, “the rule of three-dilator size increased step by step” was carried out. If dysphagia and esophageal strictures recurred during the clinical follow-up after completion of a series of dilations, additional dilatation was carried out until symptomatic relief was achieved. All procedures were performed with intravenous sedation (propofol).

Effective treatment was defined as the ability of patients with or without repeated dilations to maintain a solid or semisolid diet for more than 12 mo.

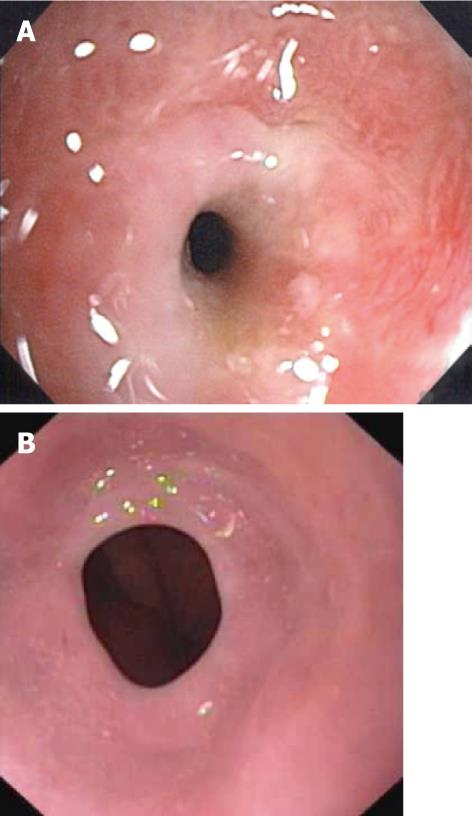

Peptic injury (Figure 2A) was the most frequent cause of esophageal benign stricture in our series in 41.6% of patients, followed by Plummer Vinson web (Figure 2B) in 27.7% of cases (Table 1).

A total of 662 dilatations in 72 patients in 141 sessions were performed. The success rate for the placement of a guide wire was 100% and for dilatation was 97%, without use of fluoroscopy, after 6 mo to 4 years of follow-up. We performed an endoscopy immediately for post procedure bleeding or mucosal tearing. After dilatation, our patients are hospitalized and observed for 6 h. They are clinically examined and in a case of pain, chest X-ray is carried out to check for perforation. Twenty four hours after dilatation, we phone patients to ask if there is any fever or bacteraemia. In our series, there were no adverse events or complications.

The number of sessions per patient was between 1 and 7, with an average of 2 sessions.

The ability of patients after 1 or more sessions of dilatation to maintain a solid or semisolid diet for more than 12 mo was obtained in 70 patients (95.8%).

For very tight esophageal strictures, we replaced the guide wire through the tight stricture into the lumen initially dilated without complications. All patients with very tight strictures had clinical improvement but we noted 3 endoscopic dilatation failures: 2 patients with anastomotic stricture because of tumoral recurrence and 1 patient with radic stenosis; these patients underwent surgery.

Benign esophageal strictures are secondary to different causes. In our series, peptic injury was the most frequent lesions, as found in the literature[6-9].

The mainstay of treatment for benign esophageal strictures is dilatation. Although dilatation usually results in symptomatic relief, recurrent strictures do occur. In order to predict which types of strictures are most likely to recur, it is important to differentiate between esophageal strictures that are simple and those that are more complex[1,10]. Simple esophageal strictures are defined as focal and straight[1,10]. Common etiologies include peptic injury (60%-70% of cases) and a Schatzki’s ring or web[10,11]. In most patients with simple esophageal strictures, 1-3 dilatations are required to relieve symptoms, with an additional 25%-35% of patients requiring repeat dilatations[11]. In our series, 76% of patients had simple esophageal strictures and needed from 1 to 3 sessions of dilations.

Strictures that are long (> 2 cm), tortuous or associated with a diameter that precludes passage of a normal diameter endoscope are defined as complex esophageal strictures[10]. The most common causes include caustic ingestion[12], radiation injury, anastomotic stricture[13], photodynamic therapy-related stricture and severe peptic injury. Complex esophageal strictures are more difficult to treat than simple esophageal strictures, require at least three dilatation sessions to relieve symptoms and are associated with high recurrence rates. If complex strictures cannot be dilated to an adequate diameter that allows passage of solid food, recur within a time interval of 2-4 wk or require ongoing (more than 7-10 sessions) dilatations, they are considered to be refractory[10]. Novel treatment modalities for refractory stricture include temporary stent placement and incisional therapy[1]. In our series, 24% were complex esophageal strictures, caused by radiation injury, caustic ingestion, anastomotic stricture and postmycosis stricture.

Successful esophageal dilatation involves both successful placement of the guide wire and dilation. This study demonstrates that Savary-Gilliard dilation can be successful without fluoroscopic control. There were no procedure-induced complications. All 72 unselected consecutive patients had significant dysphagia due to different types of esophageal benign pathology. Symptom relief was achieved in 69 patients. The results are similar to that reported by 3 authors[2,14,15]. However, in two studies, the endoscope was impassable in 5% and 29.4%. For these cases, fluoroscopy was required. During the insertion of the wire, if there is resistance or if the patient starts coughing (which indicates that the wire is inserted into trachea through the fistula), the wire should be withdrawn and reinserted. In order to prevent complications, the “rule of three” was popularized by Boyce[16]. Dilatation should be terminated when resistance is encountered during these consecutive dilations.

The main complications associated with esophageal dilatation include perforation (can occur in 0.5% to 1.2%)[6,17], hemorrhage and bacteremia. The reported rate of perforation and massive bleeding is 0.3%; this risk is higher when complex strictures[18] and caustic strictures[12] are dilated. It is generally believed that the risk of perforation is minimal if the “rule of three” is applied, meaning that dilation diameters should not increase by more than 3 mm per session[10]. Pre-dilation diameter and stricture length are established factors that influence the number of dilations required for symptom relief and the need for additional dilations[19].

In conclusion, Adequate placement of a guide wire prior to dilation is crucial to achieve successful dilation. With the technique of TTS (through the scope) guide wire insertion, endoscopic dilatation without fluoroscopy is a safe and efficacious way to relieve dysphagia, especially in benign simple strictures. Repeated sessions are necessary to avoid recurrence.

Esophageal strictures are a problem frequently encountered by gastroenterologists. Upper endoscopy is the diagnostic procedure of choice for the detection of an esophageal stricture and its underlying cause. Dilatation of benign esophageal strictures is a commonly performed procedure to relieve dysphagia. In clinical practice, fluoroscopy is recommended for monitoring the position of a guide wire and dilator. However, some authors believe that fluoroscopy is not necessary for dilatation.

In the area of treatment of benign esophageal strictures with Savary-Gilliard dilators, the research hotspot is to describe their experience using a guide wire and marked Savary-Gilliard dilators without the use of fluoroscopy and to assess its effectiveness and safety.

In the present study, the authors performed 662 dilatations in 72 patients in 141 sessions. The success rate for placement of a guide wire was 100% and for dilatation was 97%, without use of fluoroscopy, after 6 mo to 4 years of follow-up. The authors performed an endoscopy immediately for post procedure bleeding or mucosal tearing. After dilatation, the patients of this study are hospitalized and observed for 6 h. They are clinically examined and in a case of pain, chest X-ray is carried out to check for perforation. Twenty four hours after dilatation, the authors phone patients to ask if there is any fever or bacteraemia. In their series, there were no adverse events or complications. For very tight esophageal strictures, the authors replaced the guide wire through the tight stricture into the lumen initially dilated without complications. The ability of patients after 1 or more sessions of dilatation to maintain a solid or semisolid diet for more than 12 mo was obtained in 70 patients (95.8%). All patients with very tight strictures had clinical improvement but the authors noted 3 endoscopic dilatation failures (2 patients with anastomotic stricture and 1 patient with radic stenosis).

The study suggests that dilatation with Savary-Gilliard dilators without fluoroscopy is effective and safe in esophageal benign strictures, especially peptic injury, Plummer-Vinson web and caustic injury.

Savary-Gilliard dilators are polyvinyl dilators with progressive diameter (5-21).

This is a good descriptive study in which the authors report the causes of esophageal benign strictures and analyze the effectiveness and safety of Savary-Gilliard dilatation without fluoroscopy.

Peer reviewer: Ming-Jen Chen, MD, MMS, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Mackay Memorial Hospital, No. 92, Sec. 2, Chungshan North Road, Taipei 10449, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Siersema PD. Treatment options for esophageal strictures. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:142-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang YG, Tio TL, Soehendra N. Endoscopic dilation of esophageal stricture without fluoroscopy is safe and effective. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:766-768. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Cotton PB, Williams CP. Pratical gastrointestinal endoscopy. 3nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Sci Pub 1990; 59-61. |

| 4. | Geenen JE, Fleischer DE, Waye JD. Techniques in therapeutic endoscopy. 2nd ed. New York: Gower Med Pub 1992; 2: 9-11. |

| 5. | Bennett JR, Hunt RH. Therapeutic endoscopy and radiology of the gut. 2nd ed. New York: Chapman and Hall Med 1990; 19-20. |

| 6. | Andreollo NA, Lopes LR, Inogutti R, Brandalise NA, Leonardi LS. [Conservative treatment of benign esophageal strictures using dilation. Analysis of 500 cases]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2001;47:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Drábek J, Keil R, Námesný I. The endoscopic treatment of benign esophageal strictures by balloon dilatation. Dis Esophagus. 1999;12:28-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Piotet E, Escher A, Monnier P. Esophageal and pharyngeal strictures: report on 1,862 endoscopic dilatations using the Savary-Gilliard technique. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spechler SJ. AGA technical review on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:233-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lew RJ, Kochman ML. A review of endoscopic methods of esophageal dilation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:117-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pereira-Lima JC, Ramires RP, Zamin I, Cassal AP, Marroni CA, Mattos AA. Endoscopic dilation of benign esophageal strictures: report on 1043 procedures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1497-1501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Poley JW, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Dees J, Hartmans R, Tilanus HW, Siersema PD. Ingestion of acid and alkaline agents: outcome and prognostic value of early upper endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Honkoop P, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Stassen LP, Hop WC, van Blankenstein M. Benign anastomotic strictures after transhiatal esophagectomy and cervical esophagogastrostomy: risk factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:1141-1146; discussion 1141-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fleischer DE, Benjamin SB, Cattau EL, Collen MJ, Lewis JH, Jaffee MH, Zeman RK. A marked guide wire facilitates esophageal dilatation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:359-361. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kadakia SC, Cohan CF, Starnes EC. Esophageal dilation with polyvinyl bougies using a guidewire with markings without the aid of fluoroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boyce HW. Esophageal dilation. Gastroenterol Endosc News. 1986;1-3. |

| 17. | Saeed ZA, Winchester CB, Ferro PS, Michaletz PA, Schwartz JT, Graham DY. Prospective randomized comparison of polyvinyl bougies and through-the-scope balloons for dilation of peptic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:189-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hernandez LV, Jacobson JW, Harris MS. Comparison among the perforation rates of Maloney, balloon, and savary dilation of esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:460-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chiu YC, Hsu CC, Chiu KW, Chuah SK, Changchien CS, Wu KL, Chou YP. Factors influencing clinical applications of endoscopic balloon dilation for benign esophageal strictures. Endoscopy. 2004;36:595-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |